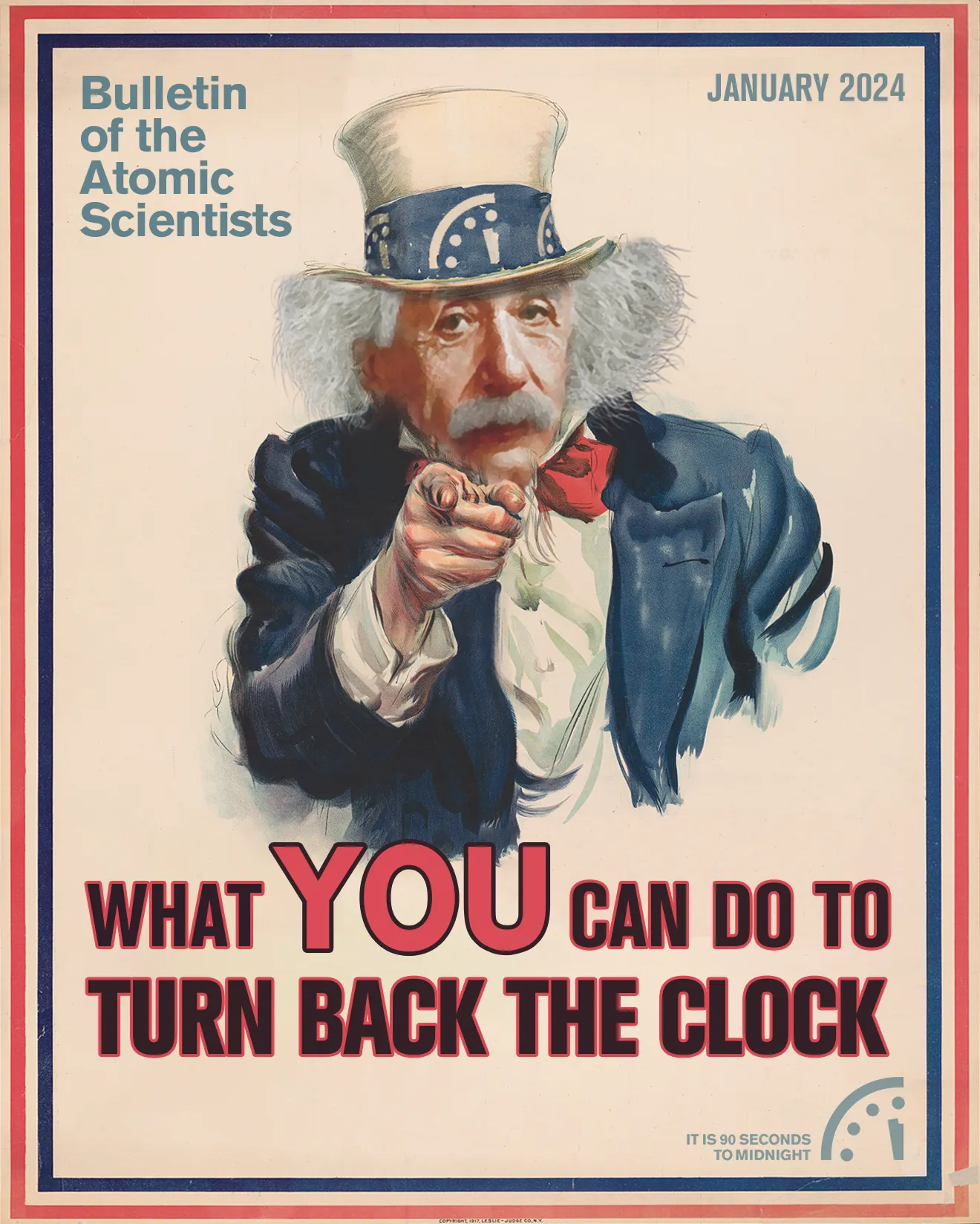

Introduction: What you can do to turn back the hands of the Doomsday Clock

By Dan Drollette Jr | January 15, 2024

Introduction: What you can do to turn back the hands of the Doomsday Clock

By Dan Drollette Jr | January 15, 2024

Every January in recent decades, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has set the hands of the Doomsday Clock—a graphic illustration of how close the planet is to the civilization-ending disaster symbolized by midnight.

When the hands of the Clock first moved toward midnight it was 1949, and the reason centered entirely on nuclear war. The Soviet Union had just tested its first atomic bomb, years ahead of when many US government observers had predicted. Nowadays, the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board considers not just nuclear weapons but a range of other existential risks—climate change most prominently, but also threats arising from a host of emerging disruptive technologies—when it decides how close the world is to catastrophe.

Each year, after the Clock is set, Bulletin staffers usually receive a flood of reader correspondence that asks some version of the same question: “But what can I do to turn back the hands of the Clock?”

Consequently, this issue of the Bulletin’s magazine—published just a few weeks before this year’s Doomsday Clock announcement—is devoted to providing at least some answers to that question. Its emphasis is on actions that citizens can take, individually and in concert, to help reduce major global threats. As much as possible, we tried to avoid merely symbolic gestures and focused on how citizens can best influence their leaders to deal responsibly with dangers that could be existential.

To provide a range of ideas, we looked for people who have been working to effect positive changes, whether on the local, state, or national arena.

For example, at the age of 15, Sneha Revanur read about the use of biased AI-generated algorithms that threatened the justice process in her home state of California. She enlisted her peers—all in high school or just entering college—in contacting voters, creating informational content, partnering with community organizations, and running phone banks. Together, they helped defeat an electoral proposition that would have enshrined the use of such algorithms in the legal system across the state. Revanur subsequently founded an organization, Encode Justice, to carry on work related to limiting the negative effects of artificial intelligence, as she explains in “Interview with Sneha Revanur, ‘the Greta Thunberg of AI.’ ”

In “Bill McKibben explains what individuals can do to win the climate fight—together,” the longtime journalist/climate change activist gives his reading of today’s climate advocacy movements and how people of different ages and backgrounds might effectively fit themselves into them. He also gives his sharp and concise views about recent politics and the transformational power of the ballot box in the battle against climate change.

For a view of effective citizen action from inside the political system, we asked Los Angeles Congressman Ted Lieu about the best ways for voters to influence their representatives on big issues like nuclear weapons and climate change. In the resulting interview “California Congressman Ted Lieu on what you can do about existential threats,” we learned that, among many other ways to get your congressman’s attention, small groups of constituents who simply ask for a meeting with their member of Congress can be effective—even, and perhaps especially, on the issue of nuclear weapons. “Many members of Congress don’t run for Congress because of nuclear weapons,” Lieu said. “So it’s just an area where I think you can get members of Congress to engage and focus on and think about in a different way, because they may not have a very strongly held belief one way or the other.”

The paths for acting individually toward a safer world are many and varied. But all of them require a degree of hope and doggedness.

As former executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (and a key player in the 2015 Paris climate agreement) Christiana Figueres notes, the world has seen dramatic progress in solar and wind power technology, huge increases in the adoption of electric vehicles and heat pumps, and significant improvements in battery storage—positive developments that have often been overlooked amid a near-constant stream of bad climate news. “The stories of what human beings have achieved by applying stubborn optimism as an input in the face of seemingly impossible challenges never ceases to amaze me,” she writes in her essay, “Why a mindset of stubborn optimism about the climate crisis is needed, now more than ever.”

Indeed, those who believe that they can succeed are usually the ones who do. In Frida Berrigans’s “How my Gen Z students learned to start worrying and dismantle the Bomb,” an experienced activist from a long line of well-known and remarkably successful activists reflects on engaging with the current generation in regard to nuclear weapons—and the urgent need to do so. Hers is a story of connection across generations, and of hope that the hands of the Doomsday Clock can be moved away from midnight. Again.

And then again, and again.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

In 1991, when the Cold War ended, the Doomsday Clock was at 17 minutes to midnight. Now it is at 90 seconds, and most likely will be further reduced on January 23, 2024. In my humble opinion which, by the way, is shared by many well-known American scholars, and even military and intelligence experts, the main reason for this reduction is the NATO non-stop expansion that started by Bill Clinton in 1998 Many prominent American experts warned against the expansion but to no avail. NY Democratic senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan warned that NATO expansion would “open the door to nuclear war.”… Read more »

You’re suggesting that NATO expansion is a cause of danger? But have you considered that countries near Russia might be afraid? Are you aware that people in Russia are subjected to a massive propaganda machine that prevents any form of change? For instance, it’s always Russia that threatens with nuclear weapons in the current conflict. No other country involved does this. Russia does it to pursue its own selfish goals. It’s entirely natural that neighboring countries are afraid and choose to join NATO voluntarily. Remember how much effort was made to talk to Hitler and engage in dialogue? In the… Read more »