Why Thomas Friedman is wrong about the National Ignition Facility

By Hugh Gusterson | April 27, 2009

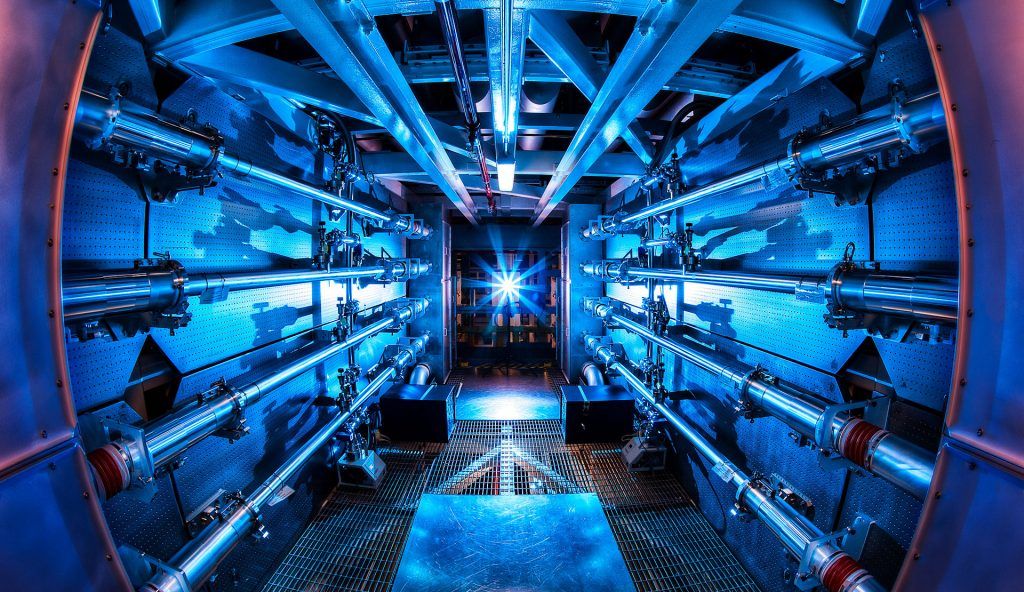

Laser preamplifiers at the National Ignition Facility. Image courtesy of LLNL/Damien Jemison

Laser preamplifiers at the National Ignition Facility. Image courtesy of LLNL/Damien Jemison

Tom Friedman’s brain is flat.

That is the only conclusion I can reach after reading his New York Times piece on Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s National Ignition Facility (NIF). A flat brain cannot tolerate complexity. It turns things—such as globalization and laser facilities—into cartoon versions of themselves.

The recently finished NIF is set to be the world’s most powerful laser system. It’s a remarkable piece of engineering. The size of a football stadium, its 192 laser arms are aligned to within 100 microns. They were largely assembled by robots to keep them super-clean, and they must converge within a few microns and a few billionths of a second of one another in order to create an evanescent star within the laboratory. Delivering more than the entire energy supply of the US electrical grid for a few billionths of a second, the laser strikes a tiny pellet of tritium and deuterium and creates transitory pressures and temperatures greater than those inside the sun—and all of this just a few hundred yards from a suburban housing estate.

It’s not clear whether Friedman knows about the NIF’s weapons connection and decided to leave it out, or whether he cut so many corners in writing his piece that he wasn’t aware of it. I appreciate that, in the harsh world of a twice-a-week columnist, deadlines are a brute fact, but there are times when a column isn’t yet ready for prime time.

Friedman touted the NIF as a possible solution to the nation’s energy problems. In his characteristically turbocharged prose, he asks: “What if a laser-powered fusion energy power plant that would have all the reliability of coal, without the carbon dioxide, all the cleanliness of wind and solar, without having to worry about the sun not shining or the wind not blowing, and all the scale of nuclear, without all the waste, was indeed just 10 years away or less? That would be a holy cow game-changer.”

He does note (at the end of the column, of course, where it won’t be seen by many readers), that he isn’t sure NIF can be made to work as a viable commercial technology. But much of his golly-gosh evocation of NIF (complete with a comparison to the USS Enterprise from Star Trek) reads like a weak paraphrase of shovel-ready prose from the lab’s public relations department. Surely New York Times readers have a right to expect more from a high-profile columnist than an embellished press release.

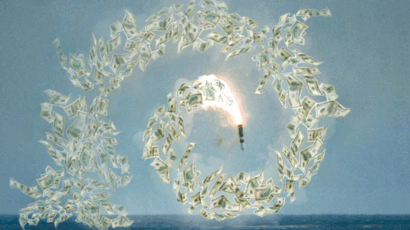

Here are a number of important points Friedman did not mention: Although the NIF has been funded through the Stockpile Stewardship Program for the nuclear weapons complex and presented to Congress as a vital facility for training a new generation of nuclear weapon scientists—ensuring that aging US nuclear weapons continue to work—remarkably, the words “nuclear weapons” never appear in Friedman’s column. Friedman is right that the NIF could be a prototype for a fusion energy reactor, and indeed, many Livermore scientists were enthusiastic about working on it for just this reason, but New York Times readers deserve to know that, thus far, this supposedly miraculous energy technology has been funded entirely by the nuclear weapons budget.

Although the NIF has become a more open facility recently, in the past those who worked on it at Livermore needed security clearances—and the details of the target capsule design were long classified because of their relevance to hydrogen bomb physics. Many New York Times readers might feel a little differently about Friedman’s miraculous new green energy technology if they knew that it was so closely tied to nuclear weapons development, and that the United States presumably would be concerned if some countries (India and Japan come to mind) began to develop such fusion reactors themselves because it could help them better understand the science of hydrogen bombs. We don’t need to repeat the mistakes of the Atoms for Peace program, when the US government enthusiastically encouraged the development of nuclear energy technology all over the world in blithe ignorance of the proliferation dangers this would entail.

Friedman also tells us that, if we want a follow-on to NIF, “a pilot [fusion energy plant] would cost about $10 billion—the same as a new nuclear power plant.” There is no mention of a source for the cost estimate, which is simply stated as fact. Not only does Friedman seem to have accepted a publicist’s number as true; he never mentions that Livermore originally promised that the NIF would cost $1.2 billion and open for business in 2001. Instead, it has cost around $4 billion (estimates vary depending on what you count) and construction wasn’t completed until this year—eight years behind schedule. In other words, buyer beware when it comes to Livemore’s cost estimates for such technology. I once asked a senior manager for the NIF how they came up with the initial $1.2 billion cost estimate. I naively thought he’d tell me that they added up all of the costs for wiring, steel, glass, and labor, but somehow underestimated. Instead he told me, with astonishing frankness, that they decided how much they thought Congress was willing to spend and worked back from there.

Given that early estimates in the 1950s substantially underestimated the cost of commercial nuclear energy, we might be suspicious of cost estimates today for a fusion plant that, by amazing coincidence, have it costing the same as a nuclear energy reactor.

The holy grail of laser fusion is “ignition”—getting more energy out than you put in. “Once the lab proves that it can get energy gain from this laser-driven process,” a breakthrough “the NIF expects to achieve” in two to three years, we can proceed to the next step, Friedman writes.

Not “if,” but “once.”

But is the NIF assured to achieve ignition? According to some accounts, there have been difficulties focusing the laser beams at high energies. Additionally, early tests showed the lasers shattering the glass lenses at the high energies needed to approach ignition. Nor does Friedman mention that Nova, the predecessor to NIF, also was supposed to achieve ignition, but Livermore scientists later found that, due to an error in their calculations, they had dramatically underestimated the energy required for ignition. Given these uncertainties, it’s irresponsible and misleading for Friedman to speak of ignition as if it’s assured.

This has implications for another issue that Friedman doesn’t raise—the expense of running a fusion reactor. He talks about the initial construction costs, but that’s all. For a fusion reactor to be a viable energy source, it would have to be fired as many as thousands of times a day, but this puts immense stress on the lenses and can burn them out. It’s far from clear that the economics can be made to work.

As one of the few people in the country who has written consistently about Livermore, I often lament that the NIF—one of the most expensive science programs in the nation’s history and an extraordinary technical accomplishment for all its problems—hasn’t received the press coverage it deserves. And I’m in broad agreement with Friedman’s conclusion: “We need to make a few big bets on potential game-changers. . . . At the pace we’re going with the technologies we have, without some game-changers, climate change is going to have its way with us.” But that doesn’t mean we should repeat the mistakes that we made in the 1950s, when techno-enthusiasts such as Friedman helped incite the global efflorescence of nuclear energy while minimizing the dangers of nuclear weapons proliferation and the difficulties of disposing of nuclear waste. By abnegating his responsibilities as a journalist, giving us instead PR masquerading as reportage, Friedman would lead us into the era of nuclear fusion with our eyes wide shut.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Nuclear Fusion Energy

Topics: Columnists, Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Weapons