How hurricane-proof is your state?

By Laura H. Kahn | September 12, 2011

Even though it was downgraded to a Category 1 storm, Hurricane Irene still packed a serious punch. My family and I spent several nights in darkness, and our front yard turned into an ankle-deep bog.Even though it was downgraded to a Category 1 storm, Hurricane Irene still packed a serious punch. My family and I spent several nights in darkness, and our front yard turned into an ankle-deep bog. But we were lucky: Hurricane Irene caused massive widespread flooding, power outages, more than 40 deaths, and is now being considered one of the costliest catastrophes in US history.

There must be some silver lining to this widespread disaster. One possibility: ensuring that the states that experience the most hurricanes are also the most equipped to handle them — with the best public health and disaster-preparedness programs. After all, hospitals that perform the most high-risk surgeries also see the best outcomes, because they have the most experience. Arguably, a similar situation exists for disaster preparedness.

Of course, all states should be prepared to respond to the myriad hazards that threaten public health, from epidemics (natural or man-made) to chemical and radiological threats to natural disasters. But, when it comes to natural disasters, hurricanes are particularly likely to test certain states’ capabilities. Why hurricanes? Unlike tornadoes, which typically cause very local destruction, and earthquakes, which are infrequent in the United States — not to mention, completely unpredictable — hurricanes are frequent, largely predictable, and cause enough extensive damage to challenge states’ wherewithal on a regular basis.

The National Hurricane Center lists the states that have been hit by the most hurricanes from 1851 to 2004. The top states are: Florida (110), Texas (59), Louisiana (49), North Carolina (46), South Carolina (31), Alabama (22), Georgia (20), Mississippi (15), Virginia (12), New York (12), Connecticut (10), Massachusetts (10), and Rhode Island (9). In addition to prevalence, these states also experienced at least one major Category 3-5 storm in that time period.

Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) is a nonprofit organization that assesses states’ public health and health care capabilities. Since 2003, TFAH has been issuing “Ready or Not?” reports that assess the readiness and capabilities of the nation’s public health infrastructure. The goal of the initial report was to assess the impact of the $2 billion invested in public health preparedness after the 2001 anthrax crisis. Scoring was based on ten indicators, including use of federal bioterrorism funding, bioterrorism response plans, and alert capacity. Since then, TFAH has been issuing yearly “Ready or Not?” reports. In 2005, the scope of the report expanded to include crises beyond bioterrorism, such as naturally occurring epidemics and natural disasters. Unfortunately, scoring criteria has changed from year to year, making comparisons across years impossible.

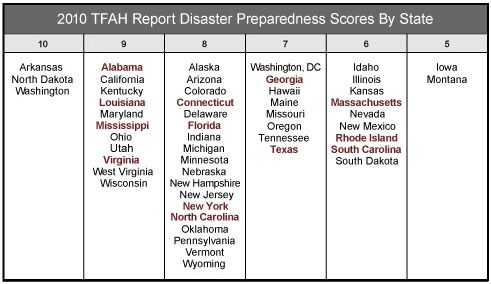

The 2010 report, however, had the most comprehensive scoring criteria — including an examination of public health funding, states’ abilities to convene emergency-response teams within 60 minutes at least twice during 2007-2008, and activation of an Emergency Operation Center, whether as part of a drill, exercise, or real incident. States received total scores ranging from 1 to 10 (10 being the highest score):

The red states are the high-hurricane-frequency states. None of the 50 states scored lower than a 5. Three states scored a perfect 10 — Arkansas, North Dakota, and Washington — and yet none of these are high-hurricane-frequency states. Meanwhile, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and South Carolina, which each scored a 6, are sometimes in the path of a hurricane and were recently waterlogged by Irene. One would expect high-frequency-hurricane states like these to score at least an 8. But this is not the case. Why?

While basing conclusions on a single report’s scoring system could be viewed as problematic, it does provide a starting point for change. It would certainly be worthwhile to find out if states’ disaster-preparedness capabilities correlate with actual disasters. In other words, states that are frequently hit by predictable disasters like hurricanes should have the best public health and emergency-response capabilities in the nation.

What should states’ capabilities include? Adequate funding, experienced, highly-trained personnel, up-to-date equipment, documented all-hazards policies and procedures, emergency operation centers, emergency response drills, integrated communication capabilities, and prepared hospitals are some of the key components for adequate disaster response.

The public must understand that state and local governments are the first responders to these crises. Political leaders who severely cut their emergency response and public health budgets ultimately hurt their defenses and have no one to blame but themselves if a disaster strikes and they don’t have the personnel or resources to react quickly and effectively.

The role of the federal government is to provide assistance to state and local governments during times of crises; its role is not to parachute in and save the day.

The public must keep tabs on what their elected officials are doing before crises develop, and they need to hold their public officials accountable. Irresponsible budget cuts could mean the difference between life or death.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Biosecurity, Columnists