Why a new anti-nuclear movement should push for an old idea: a comprehensive test ban

By Theo Kalionzes | October 6, 2014

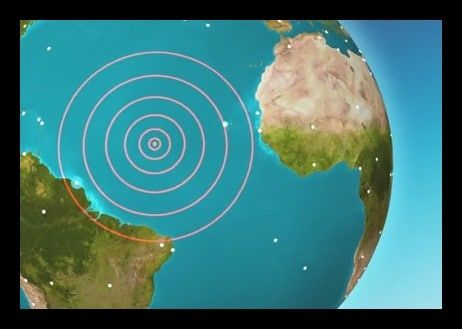

Humanitarian consequences loom large in the history of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which seeks to ban all testing of nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, below ground, under water, and everywhere else, regardless of whether the tests are conducted for civilian or military purposes. (Simulations on computers, however, are permitted.) The treaty’s humanitarian considerations have their roots in a wide variety of sources: In the early days of the Cold War, alarm bells went off after the discovery that fallout from nuclear testing boosted levels of radioactive isotopes in children’s teeth. Similarly, the 1954 discovery that Japanese fishermen suffered acute radiation sickness from their exposure to the larger-than-expected yield of the Castle Bravo thermonuclear test raised concern. Soon doctors, scientists, diplomats, and civil society organizations began calling for a ban on testing, united in their fears about its harmful effects on public health and the environment.

Meanwhile, ending nuclear tests came to be recognized as a powerful tool in the call for complete nuclear disarmament. A testing ban was thought to reduce the perceived value and usefulness of nuclear arsenals, thereby paving the way for their obsolescence and ultimate elimination. Consequently, calls for a ban on all nuclear tests made their way into the non-binding preambles of the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, which eliminated testing in the atmosphere, outer space, and under water, and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)—which sought to stop, or at least slow down, the spread of nuclear weapons. After the former drove the majority of explosive testing underground—allowing the arms race to continue unabated—advocates saw even more justification for the goal of a total ban. The CTBT finally came up for signature in 1996. Just getting to that point was a huge accomplishment; President Clinton called it “the longest-sought, hardest-fought prize in the history of arms control.”

The prize may be long-sought and hard-fought, but it still has not been won. While the UN’s General Assembly adopted the CTBT by a large majority, it still has not taken full legal effect—“entered into force” in diplo-speak—because eight countries have yet to “ratify,” a legal term that often goes beyond a leader’s signature to require consent from a country’s parliament or congress. The eight are China, Egypt, Iran, Israel, and the United States, which have at least signed it, and North Korea, India, and Pakistan, which have not. This “unfinished business”—as Rebecca Johnson of the Acronym Institute once described it—has been looming over the international community, leaving the CTBT to languish in legal limbo, even while the humanitarian argument against nuclear weapons has grown into a movement with broad international appeal.

On December 8 and 9 of this year, diplomats will gather at Vienna’s Hofburg Palace to discuss the next steps of the movement to reduce or eliminate nuclear weapons on humanitarian grounds. This is an opportune time to call for progress on the CTBT’s ratification. Partisan gridlock in Washington has dimmed prospects for US ratification in the short term, but with the CTBT back on the front burner in Vienna, diplomats could at least push for trying to overcome the reluctance of the other remaining holdout countries.

Stirring the pot. The final document for the 2010 Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty spurred the humanitarian movement onward with its reference to the “catastrophic humanitarian consequences” that would result from a nuclear attack. In a departure from the traditional characterization of nuclear weapons as prestigious guarantors of state security, this new effort reframes them as indiscriminate instruments of warfare whose use would violate international humanitarian law. The reframing appears to have given voice to many states’ long-simmering frustration with the pace of nuclear disarmament. The first two conferences—held in Oslo, Norway and in Nayarit, Mexico—attracted representatives from 128 and 146 countries, respectively. Many nongovernmental groups also attended, although the P-5 (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) stayed away.

Given the interwoven history and the shared aims of the CTBT and the humanitarian impact movement, one might assume that diplomats took advantage of the Oslo and Nayarit meetings to push forcefully for the treaty’s entry into force. On the contrary, support for the CTBT at these meetings appears to have been muted at best. A review of the official country statements made available on the Oslo conference website revealed that only two—Albania and Mongolia—directly called for the treaty’s adoption. Notwithstanding the Norwegian government’s strong support for the CTBT, the Oslo chair’s summary failed to mention CTBT implementation (although it did refer to the human cost of nuclear testing). None of the official statements made available on the Nayarit conference website calls for the treaty’s entry into force; although the Nayarit chair’s summary does refer to the goal of bringing the treaty into full legal effect, this was not a point of emphasis.

And the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty needs all the help it can get. Although 183 nations have signed, it faces corrosive political uncertainty precisely because it has not yet taken full legal effect. Seven other countries must still ratify the treaty to bring it into force; the conventional wisdom among treaty-watchers is that none of them will do so unless Washington ratifies first. According to the logic of this argument, while US leadership was instrumental in moving the CTBT from the drawing board to the negotiating table in the 1990s, the Clinton administration’s failure to win ratification in 1999 removed the sense of urgency upon other holdout countries to ratify. Once the United States ratifies—says this argument—China will quickly follow suit, increasing the pressure on others to bring the treaty into force.

In 2009, President Obama pledged to “immediately and aggressively” pursue ratification, but partisan acrimony on Capitol Hill and conflicting domestic priorities have made it all but certain that it will not take place on Obama’s watch. This assessment could lead advocates to conclude that the most viable strategy is to call for a timeout until a new US president is elected, hoping for improved future prospects.

This is a risky strategy. If there is no progress on making the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty legally binding, then the sustainability of the entire CTBT cannot be assured. What’s more, US ratification alone—while a necessary step—is not sufficient to make the treaty go into force; there is still the matter of those seven other holdouts.

The current situation will require a renewed push at the multilateral level, and the December humanitarian impact conference would be a good place to begin. The administrators of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization recently launched a promising venture called the Group of Eminent Persons, which aims to promote the treaty’s entry into force by convening high-level strategy groups of experts and politicians, including luminaries such as former US Secretary of Defense William Perry, and Hans Blix, former International Atomic Energy Agency director general.

Uniting the humanitarian impact movement and the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty would be a natural fit, and there is reason for optimism: The December conference will be held just a stone’s throw away from the CTBT’s Vienna headquarters. This closeness in space and time is propitious. If the humanitarian impact movement were to join forces with the Group of Eminent Persons in December, it could go a long way in building the support needed to make the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty—long-sought and hard-fought—go into effect.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, Opinion, Technology and Security