Why the NPT needs more transparency by the nuclear weapon states

By Paul Meyer, Henrik Salander, Zia Mian | April 8, 2015

A growing accountability crisis is likely to be a core concern when the 189 states party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) meet for a Review Conference in New York in April and May. At the heart of the accountability issue is a simple question: How can the signatories to the NPT, and the world, be confident that there is real progress toward meeting the disarmament goals of the treaty?

The NPT entered into force 45 years ago, and one of the treaty’s core obligations is nuclear disarmament, as set out in its Article VI. The NPT’s nuclear-weapon states (the US, UK, France, Russia, and China) have insisted they are making progress toward this goal. Despite this claim, an estimated 16,000 nuclear weapons remain today, and there are no talks on an international treaty to ban and eliminate nuclear weapons.

Many non-nuclear weapon states—which by signing the NPT agreed not to develop nuclear weapons, so long as the weapon states disarmed—have expressed their wish to see greater transparency on the part of the nuclear weapon states in detailing their disarmament actions. In successive meetings, NPT members have tried to specify “benchmarks” for measuring progress toward the nuclear disarmament goal. These measures include notably 13 "practical steps" agreed at the 2000 Review Conference and 22 “action items” on disarmament adopted at the 2010 Review Conference.

Among the action items from 2010 was a call for the nuclear-weapon states “to agree as soon as possible on a standard reporting form and to determine appropriate intervals for the purposes of voluntarily providing standard information…” A related item required the nuclear-weapon states to provide an initial report on their implementation of nuclear disarmament commitments by the April 2014 NPT Preparatory Committee meeting, for subsequent review at this year's Review Conference.

At the first meeting of the current NPT review cycle in May 2012, the 12-nation Nonproliferation and Disarmament Initiative grouping (all of whom are non-weapon states) proposed a reporting format that represented their judgement of what is required to make an informed assessment of relative progress in meeting the treaty’s disarmament commitment. The proposed format sought information on the number, types, and status of nuclear warheads held by the weapon states; the number and types of delivery vehicles; specific information on warhead and delivery system dismantlement and reductions; and the amount of fissile materials (plutonium and highly enriched uranium) that are the key ingredients for nuclear weapons produced for military purposes.

The International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM) (of which the authors are all members) offered its own recommendations for nuclear weapon states reporting in its Global Fissile Material Report 2013: Increasing Transparency of Nuclear Warhead and Fissile Material Stocks as a Step toward Disarmament.

For their part, the five NPT nuclear weapon states duly submitted their respective national reports to the 2014 Preparatory Committee session and proclaimed their satisfaction with “the achievement of … consensus on a common reporting framework.” Examined objectively, however, these “achievements” offer little to crow about. In fact, it is likely that non-weapon states at the NPT Review Conference will be significantly dissatisfied with these weapon-state national reports.

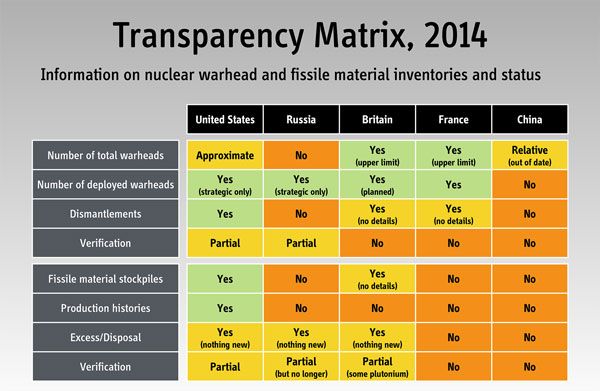

The only things common to the national reports provided by the nuclear weapon states in 2014 were their tables of contents. The five reports differed significantly in terms of structure, reporting categories, and substance. While there are actual numbers and types of deployed forces included in some reports, in others the descriptions lack the qualitative or quantitative specificity that would permit comparative analysis. (See the IPFM report card on these five national reports above.)

The Chinese report, for example, cites comments from Chairman Mao Zedong regarding the “small number of atomic bombs” that China will produce and asserts that “China’s nuclear arsenal is very limited in scale and is kept at the minimum level required for its national security.” This is an affirmation that provides precious little insight into Chinese nuclear arsenals or disarmament intentions, particularly given that Mao died nearly 40 years ago. Fissile material stockpiles are not addressed at all.

Russia’s report yields a few more numbers, but does not really provide a basis for assessing contemporary action on nuclear disarmament. The report reiterates the limits set on strategic nuclear forces by various arms reduction agreements over the decades and claims that “Russia’s non-strategic nuclear capability is no more than 25 per cent of the level of capability which the USSR possessed in 1991.” This seems an impressive sounding statement, but lacks sufficient information to arrive at an answer as to current levels of these weapons. As for fissile materials, Russia reported only that “[b]ack in 1989, our country ceased to produce highly enriched uranium for nuclear weapons. Since 1994, Russia has not made plutonium for nuclear weapons. The last reactor producing weapons-grade plutonium was stopped in the middle of 2010.” No mention is made either of historical or current stockpiles of fissile material.

Britain and France announced no significant new information in their 2014 reports, choosing only to repeat previously declared upper limits on their nuclear arsenals. Britain reported that "[t]oday we have fewer than 225 warheads, all of a single type" and that "[w]e have committed to reducing this maximum stockpile to no more than 180 by the mid-2020s, with the requirement for operationally available warheads at no more than 120." France reported that it "possesses a total of less than 300 warheads" and “no non-deployed weapons. All its weapons are operational and deployed.” Neither country reported on the size of national fissile material stockpiles.

The United States offered more details, but here, too, there was a lack of complete and timely information. The United States declared the number of nuclear weapons it held as of September 30, 2013 (the total stockpile of nuclear warheads declared to be 4,804). But, it reported additionally a stockpile of “many thousands of nuclear warheads” that were retired and in the dismantlement queue. The United States also reported its holdings of fissile materials, declaring the size of stockpiles both of plutonium and of highly enriched uranium—but as of 2009 and 2004, respectively.

The NPT reports by the weapons states share a tendency to use reference points situated long in the past to hide a reality: The pace of reductions and destruction of nuclear warheads has slowed considerably between the two nuclear superpowers, and reductions by the other weapon states are not transparent. Further, the nuclear weapon states are largely silent about any future nuclear reductions and about the size and disposition of their fissile material stockpiles. The absence of accurate, up to date, and complete information and standardized reporting categories obscures the facts about disarmament by nuclear weapons states, both for other NPT states and for the public.

Improved reporting by nuclear weapon states would demonstrably strengthen the accountability mechanisms of the NPT and sustain its authority. Held once every five years, the NPT Review Conferences provide a reasonable and relevant timeline for regular reports by the nuclear weapon states on their progress toward meeting their disarmament obligation. Reports to these conferences should include both base-line historical data as well as what has been accomplished specifically in the previous five years.

It is to be hoped that the nuclear-weapon states will recognize that an enhanced reporting process—one that includes requirements for substantive and comparable data—should be an outcome of the 2015 NPT Review Conference.

Editor's note: The table accompanying this article was designed by Alexander Glaser, Princeton University and IPFM.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.