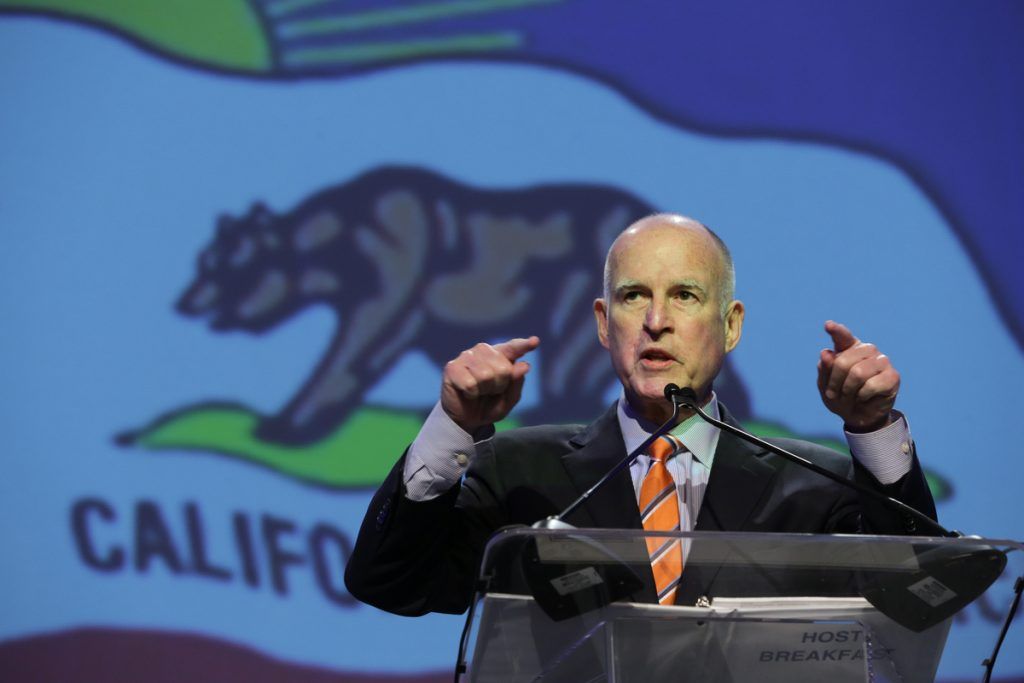

Jerry Brown on climate change, nuclear weapons, and the Doomsday Clock

By Jerry Brown | December 7, 2015

Editor's note: The following is an adaptation of remarks California Gov. Jerry Brown made at the Bulletin's 70th anniversary Doomsday Clock Symposium in November, in Chicago.

A clock symposium—I’ve never been to a clock symposium. In my mind, I drifted to a poem that I read when I was a freshman at the University of California, by William Butler Yeats; it’s called "Leda and the Swan." I don’t know how many people know of "Leda and the Swan"—it’s about the ravishing of Leda by this very powerful swan, and one of the lines in the poem is: “Did she take on his knowledge with his power?” And that’s what we’re talking about; we’re talking about knowledge, and we’re talking about power. They’re not the same thing—knowledge can generate power, and power can generate knowledge, but they can also move on separate tracks. And power can be mindless, and therefore not reflect any deep knowledge. Actually, I thought I misremembered that poem only until I just looked it up. I thought it was, “Did she take on his wisdom with his power?” And so, that’s another thing entirely, because you can have knowledge, but does that add up to wisdom? And those are the two categories that I had thrown at me many times in my Catholic education. Knowledge is not wisdom, nor virtue for that matter. So we are going to have to do more than just generate knowledge, we’re going to have to generate some wisdom and some virtue and, I guess, emotion to get people excited to do something.

I’ll try to do my speaking knowledge to power. Now, you have a lot of knowledge, but I have some of the power. And you are speaking to me, and that’s good. I mentioned last night with some of you, that this problem of big problems—the threat of catastrophic change—if you speak about it so as to be clear, about what it is you’re speaking about, and try to really scare people, you run the danger of being called a kook. In fact, somebody who interviewed me the other day said, “Well, aren’t you going to be viewed as a kook if you keep talking about these existential problems?” So I won’t scare you, because I certainly do not want to be viewed as a kook, but I don’t want you to be complacent either. And that’s the other problem; if you don’t say much, if you don’t speak in the language commensurate with the problem, then people don’t hear and don’t understand and won’t get the knowledge. And, too often, those with all this power are not sharing what they know.

And so I’m trying to do a little of that, because I’m not a sociologist, I’m not a political scientist, I don’t know much about physics, I don’t even know much about STEM. I took my degree in Latin and Greek, one of the last American politicians to get a classics degree. And it does come in handy, because some of the same mistakes have been made over and over again. and you can find examples of everything we’re doing, right or wrong, in ancient Greece or in the transformation of the Roman republic into the empire that collapsed in the face of these fanatical Christians who liked to have themselves eaten by lions. What would we think of that today, by the way? Anyway, people do extreme things—and extreme things, extreme ideas, extreme actions do change the course of history.

So, what I know about is a little bit about the political decision-making. I know a little bit about politics—it’s just that I know a fair amount about it because I’ve been thinking about it for a long time, more than 70 years. My father ran for district attorney in San Francisco in 1943; I was five. The dinner table conversation was a lot about politics, elections, and all the different people, the forces and interests. So I’ve been thinking about it and watching every election from an early age. I’ve probably run—well, I know I’ve run for president more than any other living American. And I’ve also—well, I won’t say, that’s a whole other little story. But you do actually learn something when you’re unsuccessful, you learn a good deal. So I do know about the government and the politics and how things work.

In these two topics—climate change, which I want to talk about, and the nuclear arms race—you run into this problem of news and how we communicate. And I have to tell you, the nuclear arms race is not news. Climate change is not news—it isn’t. Hillary’s emails are news, Gerald Ford bumping his head coming out of the airplane is news, but climate change and the nuclear arms race are not news. Because news, as was said facetiously, is not dog bites man—that’s not news—but man bites dog. It’s incongruity; it’s an event, it’s not a process. For the most part, now, there are commentators and all the rest. But if you look around the paper, and you look at the news, you’re not going to hear a lot about what we’re talking about today, even though it’s so important.

So I do want to talk about climate change, and I think there’s a connection there with the nuclear arms race: They both have catastrophic consequences; they both are such that they don’t capture the popular imagination right now. They both take widespread collaboration across many countries. They’re a little different in that climate change I think is subject to more popular impact in grassroots groups, whereas I think the nuclear arms race could be improved greatly when just a few people come to some deeper agreement.

Anyway, climate change: I know there are issues about how we’re doing, and how we can do, and this is going to depend upon Paris. Even getting to 2 degrees (Celsius of global warming) is a real question. In fact, I’d say many people think that we’re not going to be able to do that. But even if you get to 2 degrees, that only says we have a 50 percent chance of stabilizing the climate system. So the 2 degrees isn’t the greatest victory; it’s kind of the minimum that’s required.

Like the nuclear arms race, climate change has people on a mission. People were talking about President Obama’s climate change maneuver. Senator Mitch McConnell sent a letter to all the governors, and I got my letter, basically just undermining President Obama’s effort not only from the clean air initiative of the EPA but also what he was doing regarding Paris. He was basically saying, “Don’t listen to Obama, whatever he does will not be accepted by the Congress.” So it was just basically kind of an act of insurrection by the majority leader of the Senate, and that’s a pretty big … I mean, it’s amazing.

So, there is a lot of denial in California, even though we have a lot of advanced policies, and some very good laws have been signed in recent times, although not at the beginning. There were no Republican votes for anything that relates to climate change or global warming. There were a few years ago but, increasingly, climate change is not even mentionable.

It reminds me very much—I was in a pre–Vatican II seminary, and we did have a very narrow range of permissible topics, very narrow range. In fact, the only books that we could read were the New Testament and the lives of Jesuit saints. If you wanted to read about a Franciscan you had to get permission. Even reading the Old Testament required permission. So I appreciate narrowing the intellectual focus—and I did spend three and a half years in a pre–Vatican II Jesuit seminary, and I got the full impact of all that, and there are a lot of lessons there. I talked to a governor in the last three years; he said, “I’d like to work with you on renewable energy.” He actually said, “But I can’t use the word ‘global warming,’ I just can’t.” Because he was a Republican, and he’d get in trouble.

So, even though there are big, discouraging facts—namely that the majority of the Congress doesn’t want to do anything—the same was true, I think, with nuclear arms agreements as well. But there’s some good news. In California, we are getting things done—and in the face of a lot of criticism.

People said, “Why are you doing anything?” California is only (an emitter of) one percent of global greenhouse gases, but we have pioneered ahead. And I think it’s important to realize how and why California is so positioned. It’s not something I started four years ago. No, this has been going on a long time. In fact, the central power that California exercises was brought into being in an agreement between Gov. Ronald Reagan and President Richard Nixon in 1969, when the Clean Air Act was amended to recognize California’s right to promulgate stricter tailpipe emission standards. And that of course was driven, probably, because of the smog in Los Angeles and because of the well-used term “smog.” In fact, there was a Republican supervisor, ran for supervisor in Los Angeles County, long since dead, but he had this motto: “S.O.S, Stamp Out Smog.” And so, a lot of Californians were sensitive to that, and that meant that the Clean Air Act wasn’t good enough for California; it was just treating everybody the same.

So with that exception, California has been adopting stricter standards on tailpipe emissions, these are the criteria— pollutants like NOx and sulfur, ozone. But recently, in fact under the democratic Governor Gray Davis, the Pavely bill was signed—the first emissions restrictions on vehicles based on reducing greenhouse gases. I think that was the first time that was done anywhere. Now, in order for that to work and to be effective, the federal government—the EPA—has to give you a waiver. And under the previous administration, no waiver would be given. Around the same time, a lawsuit was filed against the EPA—Massachusetts and California v. EPA—and the question was: Is carbon dioxide a pollutant? Do you have to find it endangers human health? The Supreme Court ruled 5-4, yes, it is a pollutant under the Clean Air Act, and therefore it can be regulated. And therefore the California Clean Air Act or the California Air Resources Board can regulate it. And it took many years. In fact, when I was attorney general, I appeared before the EPA to argue for the waiver, but it was only when the Supreme Court ruled that California had that ability. And under President Obama, we got the waiver and it’s been in effect. And based on that and the bankruptcy of the automobile companies, President Obama was able to take the California standard and impose it nationally.

But notice what happened, something happened in California—really it happened in Los Angeles—and from the response to smog in Los Angeles, California was able to drive the existing national standard for automobile emissions that include greenhouse gases and other pollutants. So California has been pushing the envelope. Even before that, I have to go back— I’m giving you this history, I want to show you that things get done by many hands and many minds. There’s not a quick one-person, one-man band kind of operation here. When I was elected governor for the first time, California had an Energy and Resources Conservation Commission. Now that was created by Ronald Reagan, the governor before me, and he had vetoed that bill before. But then there was an oil embargo, and people were demanding that something had to happen. People were talking about America becoming independent in our energy, and he wanted to be able to build more nuclear power plants, but all the local authorities would delay things. So what he wanted was a one-stop shop to produce a lot of power plants, to get California fully energized. But the Democratic majority added conservation and monitoring and energy forecast and research and gave it a much fuller mandate.

So when I became governor, there was this very powerful agency that had no employees because its first day was my first day in office. And I took someone who worked with me, I made him chairman—and to show you that, you know, people hang on long in California, I was able to make him chairman of the Independent System Operator, which is the entity that manages the short-term and long-term flow of electricity in California. So, there’s a lot of continuity there. Anyway, we built that agency up to several hundred people.

The building standards took eight years to get and they affect every building in California, every building to be built after 1982. And those standards are different for Palm Springs or for San Francisco or for Lake Tahoe; there are many zones. So the rules are sophisticated. They were well-thought-out and, by the way, they were strongly resisted. I had to fight the developers. In fact, I was running for the Senate, which I lost—one of the many times that I’ve lost, but it doesn’t matter how many times you lose if you win more. So anyway, I finally got those standards out. They said those standards were terrible, it was going to stop development—bad. But finally we put them out. And in fact, we put them out the day I left office—not totally courageous, but maybe politically smart. We got them out.

And the same people then, maybe a year later, put out appliance standards affecting refrigerators and dryers. So, California had its own energy efficiency standards. In fact, they were so impressive that in the administration of President Reagan, who had gone from governor to president—the federal government passed a “no-standard” standard and preempted California’s standard with nothing. And the federal government can do that; they say, “We have a standard, therefore you can’t have one. But our standard is ‘no-standard.’”

But after a while, even the federal government started doing appliance standards. And our buildings, by the way, have saved tens of billions of dollars over the course of those three decades. So, we’ve got building standards, we’ve got appliance standards, we have a very strong tailpipe emission bill, and then Arnold Schwarzenegger, who followed Gray Davis, he signed the Global Warming Solutions Act—that was AB 32. And that measure, well—I don’t know that there is any other state that has quite adopted something like this. This bill sets forth a goal for the percentage of electricity to be generated from non-fossil fuel sources.

It does a number of other things but I’ll just mention, on the electricity, the utilities said, just a couple of years ago, that the goal of 20 percent renewables by 2020 was impossible. Today, they are generating 25 percent of electricity—not counting hydro or nuclear. But they didn’t think they could do it. And now they’re doing 25 percent, and in San Diego, Sempra electricity utility is generating 40 percent today. So when people talk about “oh, 20 percent”—well, in California we’re going to be at a third in three and a half to four years. And we will be at 50 percent, I think, by 2030. So that’s on the electricity side.

Then we developed a cap-and-trade system (for carbon dioxide emissions). We’ve had many auctions under our cap-and-trade system. It’s actually working, we haven’t detected any cheating. This year it will generate between $2 billion and $2.5 billion that is paid by those who buy the credits because they can’t meet the standards; they don’t meet the caps so they’ve got to buy the credits from somebody. And the people who buy them, it’s all secret, so you can’t know who buys them, but you can speculate the main people who buy them generate greenhouse gases, and so many of them are oil companies that are doing their very best to end the cap-and-trade system and to really resist serious climate change. So the cap-and-trade system is working, and we take that money and we put it into energy efficiency, research; we pay electric car buyers. There’s a subsidy for that—and many kinds of projects, technology and what have you. So that’s working.

Six years ago, when I was attorney general, I proposed a bill to require the utilities to invest and create 1,300 megawatts of storage. They said it can’t be done; they fought it. But then a couple years ago they relented, and we passed it—passed the law that said they had to have 1,300 megawatts. They have already contracted for about half of it. And I know Southern California Edison has already bought 250 megawatts of storage. So what was impossible becomes possible, and the engine of that is nothing other than precise, coercive, implacable regulation. That is exactly what it is—do it or else. That’s called demand and control. But in that process, you have to know: Are you demanding enough, or are you demanding too much? You’ve got to push them, but it does take some wisdom and knowledge.

We also have something called a low-carbon fuel standard. The low-carbon fuel standard is one of the most unpopular items that the oil companies love to hate. And in fact, Washington copied the California low-carbon fuel standard, and when a bill was coming along to fund a road building program with insufficient funding, the Republicans inserted a poison pill—that if the Governor signs the road bill, it will make illegal, by that act, the low-carbon fuel standard. And he ended up signing that; I guess he felt he didn’t have a choice. But it shows you how strong they are.

How do you deal with that? Well, I talked to a couple major CEOs of oil companies, and to one of them I said, "Send your people up, and let’s talk about the low-carbon fuel standard." He sent four of his best people, twice, for two-hour meetings, and we argued back and forth. The standard is very well-defined; everybody knows what it requires, and it will kick-in fully at 10 percent of all fuels used in vehicles in California by 2020. So the question is, is this low-carbon fuel, as defined, available? Going back and forth, we got, “Well, we could probably do 4 percent.” And our (Air Resources Board) engineer said, “I think they can do 7 percent.” We don’t quite know how to get to 10 percent yet. So it takes understanding, it takes real knowledge, you have to listen to the other side, and you have to know when to push and when to compromise and modify. We are in the middle that process right now.

Zero-emission vehicles—that was a story. If you’ve seen the movie Who Killed the Electric Car?—I don’t know how accurate that was. But we had an electric car mandate in California under our Air Resources Act, but that didn’t work… But now, just a few years later, California is buying 40 percent of electric cars. We’ve got 150,000 zero emission vehicles on the road. It's lower oil prices that make it more difficult, but still, (the program) is growing. And we’re looking at various ways that we can accelerate that. So, there is actively something happening.

Now, when you say all this, people say, “Well, you are going to hurt the economy.” If you listen to that minority party debate—I guess I can’t call them minority party in Congress—but in that Republican debate they all, when asked about climate change very briefly, they said, “I am not going to do anything to wreck the economy.” Well, California is not wrecking the economy. Our economy has been growing faster than the national economy, compared to the trough of the recession.

In fact, now it’s growing faster than Texas. Texas grew very well because of that nice oil price, and when it went down, so did their economy slow down. Ours, because of its housing and a lot of mortgages, went way down, and now it’s coming way back, for many reasons. I wouldn’t attempt to specify what all the factors are that are causing California’s economy to grow. But one thing we know is that the environmental regulations—they may be stopping someone, but the economy is still going. They say the same thing about a tax. They say, “If we pass this tax, that will hurt the economy.” Well, the economy has been growing. So there are many factors, and you have to really look carefully and see whether something is worth it or not.

And in the climate change debate, people keep saying “cost-benefit.” But, if I can rely on Nicholas Stern in his book, Why Are We Waiting?, he said there is no climate model that has ever measured, or attempted to measure, a world of 3 degrees Celsius (increase in temperature). It doesn’t exist. So when people tell you this is the cost of some climate initiative, they can’t tell you that. Because nobody knows. If we do nothing, as is recommended, and we get to 3 degrees Celsius, then what are the costs? We know they’re going to be big, but we don’t know exactly. So this “cost-benefit” which they keep talking about, they firmly believe that if you have 25 percent renewable energy, your economy wouldn’t work. Well, it is working, and California is an example. I’m not saying we’re perfect—there are lots of issues, we have plenty of problems. But the consistent work over several administrations to protect the air has had good benefits.

And also, for example if you look at Los Angeles, if you look at the number of cars—I don’t know what the number is, two or three times more than it was four years ago—but the air is 90 percent cleaner. I would show that to the Chinese and say take a look: If you want to get rid of the short-lived climate pollutants like soot and methane and NOx and HFCs and all the rest of them, that’s good for your health. It is good for the climate. And it’ll make your breathing a lot better. So this cost item is belied by the evidence. I think California is a good example of that, but there is opposition, and you’ve got to fight back.

Now because I realize that California keeps going it alone, and our cap-and-trade does add to some costs, our low-carbon fuel is going to add some costs. Our 50 percent solar—we don’t know. It was just a couple of years ago that people on the Public Utilities Commission were warning me of sticker shock on the electric bills, and now they are far less concerned about that, even though we are even more aggressive on renewable energy. But because we don’t want to just be an isolated place, we’ve developed—the people that work with me, the Air Resources Board—we developed an Under 2 MOU (memorandum of understanding). The Under 2 MOU, which we started several months ago, has now been signed by 57 states, sub-national jurisdictions, and even countries. Provinces of China, Brazil, Baden-Württemberg, North Rhine–Westphalia, Quebec, Ontario, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon—they have all signed it, along with many others.

The accumulated gross domestic product of all these signatories is more than the United States itself, so it covers a lot of people. So we are not waiting for Paris. We want Paris to succeed but there is still something you can do, and that’s the good news. There is action that can be taken, and we are taking it. Now what does it require? It requires that, by 2050, greenhouse gases be reduced between 80 and 95 percent. Or that the average per capita emission is two tons. In California it is about 11 tons per capita; America is about 19. (That’s in the ballpark; we’re 11 or 12.) If you add up the total—and we do measure this stuff—we are at about 450 million tons (of carbon dioxide), and we expect it to be at 425 by 2020, and by 2030, our goal is 265, which is going to be extremely challenging. It’ll need a lot of technology, a lot of political will, but we’ve set the goal, and all these people have signed onto it.

We have some other elements in the Under 2 MOU. We have mid-term targets to support the long-term goals. We are agreeing to share technology, research, and our better practices that promote energy efficiency and renewable energy. We are going to agree to collaborate on the use of zero-emission vehicles, we are going to take steps to ensure consistent monitoring and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions—and we are doing that now with China. The Chinese government sends people to the air resources office in California, and we send people over there. And we are working with several provinces, we are working with the National Development and Reform Commission.

We are also committed under this Under 2 MOU to reduce short-lived climate pollutants. And we’re told that if we seriously reduce the short-term climate pollutants, instead of having to achieve our goal by 2050, we will get another 10 to 15 years. Because if you can take out the short-term climate pollutants, as they are so many more times more impactful and heat-trapping, you will have a little more time to achieve the CO2 goal. You scientists can critique that point, but that is from UC San Diego professor (Veerabhadran) Ramanathan,who is really passionate about spreading this.

So, I would just say that there is some good news. While we have the majority leader, Sen. Mitch McConnell, writing letters to all the governors, saying undermine America’s position at Paris. When we have the head of the environmental committee holding up a piece of ice and then deriving the conclusion that it’s all a hoax—that’s pathetic. So it’s not just about one Oklahoma senator; it’s about an entire culture (in which) that could plausibly even show up without being laughed right off the stage. But there is good news, and we are doing stuff in California on climate change.

Now on nuclear, I’ve been interested in this for many years. It’s a topic that interests me because I am interested in things that can make a difference. I did spend all this time in the seminary pondering the eternal verities, and, because of that, I am kind of oppressed by the deeply superficial nature of most of my existence and that of others that I encounter. So whenever I find something really important, existential, outcome determinative, I get very engrossed in that. And that is the reason why I have been so interested in the environment, because it does make a difference. It’s not like dietary requirements. It’s not like pairing the right wine with the right meat or something.

California is so full of low-priority needs. In fact, I have to tell you something about needs, because needs are the whole issue. What I have found is, and I have developed a hierarchy: First we get a desire; and then the desire is transmogrified into a need; and then we get a law; and then we get a right; and then we get a lawsuit. And we have thousands of these in California. And I feel like I am constantly just fighting off all these lawsuits that emanate from desire.

And besides being in the Jesuit seminary, I also went to Japan and I did six months of Zen meditation. And at night before we would go to bed, the monk would intone: “Desires are endless; I vow to cut them down.” Now, I have not found that a political platform that works in California, which is a complete state of desire. But, at least, it makes me think.

But now, this business of dealing with climate change and reversing the nuclear arms race—that is a need. That is so fundamental, and there are not too many ways to deal with this. And this (Doomsday) Clock is one graphic, pictorial representation that is profoundly important. And we get back to this problem: If you scare people, or if you sound catastrophic, then you are a kook. But if you don’t wake everybody up, we’re doomed. And somewhere between those two, I think that Clock fits squarely, right in between the Scylla and Charybdis of the dilemma.

Now I do want to say something about nuclear, something that isn’t quite germane, but I think it’s interesting. I did a seven-day retreat under an elderly Jesuit, he was 89, this was in 1986 outside of Tokyo. Father Lassalle, a German missionary who left Germany in the 20s—his area of work was Hiroshima. He was there on the day that the bomb dropped, and he walked out. I asked him, and he said, “I couldn’t feel anything. And it struck me as strange—when a friend of mine, several years later, died, I felt really bad. So I felt bad about a friend dying, but I couldn’t really relate to this devastation.” And that, I think, represents our problem—that it’s so vast that the human mind has a hard time grasping this. Again, that’s why the Clock is important: Telling time is a little easier than grasping these large things.

In the '80s, one of the priests who taught me in school asked me to write a response to (former Defense Secretary) Caspar Weinberger’s article. This was in Thought Magazine, a Jesuit publication that no longer exists. Weinberger wrote a piece, and this priest asked that I write an answer, so I did. Before coming, I thought I would dust off this 31-year-old document and take a look at it, and what I find concerning but hopefully instructive: Weinberger in this article, because this was a theological publication, he quotes Moses as saying, “I set before you life or death, blessing or curse. Choose life, then, so that you and your descendants may live.”

And what did Weinberger mean by that? He meant to support Reagan’s $220 billion, 7,000-new-warhead program—that’s what he meant by choosing life. So that’s what we are up against. If a serious person like Weinberger—I take him as serious—could think choosing life is 7,000 nuclear warheads with 170,000 times the power of Hiroshima, and not death… I hope they don’t think that way anymore. Maybe they read my response, and they would know how bad that kind of thinking was.

Anyway, my thought was that this arms race has the quality of an addiction. In an addiction, you take your fix but after you take the fix, you have to take it again. But as you take the fix to ward off the anxiety, you always have to take more. So the variables keep increasing. And so in the arms race, in order to deter, the other side deters; and then we deter—it’s a symmetrical kind of escalation. How does it end? The only response is more deterrence. And deterrence is a nice word, but it means weapons of mass destruction. So there is the dilemma. And really at the end you have to find—I know it’s heretical, I know it’s politically incorrect—but at some point there has to be a form of mutual trust. That is the way destructive addictions and an arms race has to end—or it explodes, and it ends.

Now, not naïve trust, but building some way forward is a way to deal with this addiction. We’re building, the Russians are building. Who started it by the way, who started the latest round? Finger-pointing is not going to help. Name-calling is not a policy. We’ve got to get to the basics: Reasonable steps forward on both climate change and nuclear. And we’ve got to get serious about both our inertia and our complacency. Because these are manmade problems, and human beings can deal with them, can make them go away, ultimately.

And that’s the challenge. And there are not a lot of people doing it; this is a small group. And I don’t know if you know how isolated you are. Nobody is worrying about nuclear arms. And not that many people worry about climate change. We’ve got a lot of climate change talk around here. I can tell you as a politician, if you want to bring a crowd to its feet, don’t talk about climate change. Unless it’s the Sierra Club or some young people or something. But generally, normal people don’t want to hear about climate change and they certainly don’t want to hear about the nuclear arms race. So our only hope is that Clock; you better tend it well. Thank you.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Climate Change, Nuclear Weapons