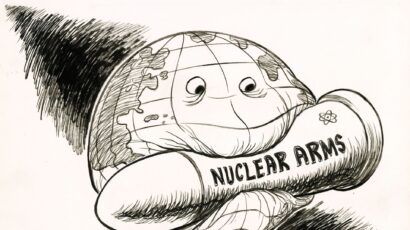

Can Rouhani deliver on the Iranian nuclear deal’s economic promise?

By Amir Handjani | March 9, 2016

Last month, six weeks after implementation of the Iranian nuclear accord, parliamentary elections gave Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and reformist politicians a clear mandate. Despite recent successes, though, Rouhani can hardly rest on his laurels. Backers of the centrist cleric will now look to him to breathe new life into their country’s stagnating economy. While Iran boasts the second largest economy in the Middle East (after Saudi Arabia), it has been hit hard by years of sanctions, international isolation, and corruption. Since Rouhani was sworn into office in 2013, Iran’s economy has experienced modest growth; the GDP grew last year by 3.8 percent after three years of economic contraction. Inflation, which peaked at 40 percent in 2013, stands at 13 percent today. Yet the rate of youth unemployment is a staggering 25 percent. For a country of 77 million people who have endured tremendous hardship over the last decade, the nuclear deal represents Iran’s best opportunity to achieve much-needed economic reforms.

There has been considerable rancor, in some quarters, over the sanctions relief Iran received under the deal it signed with six world powers (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) in exchange for scaling back its nuclear program. Hawkish Republicans in the US Congress are in an uproar, believing that with some sanctions removed, Iran will use windfall profits from oil revenue to fund activities hostile to Western interests. This view shows they do not understand the challenges the Rouhani administration faces in trying to stabilize the Iranian economy after decades of mismanagement and amid a precipitous drop in oil prices. Indeed, Iran is reentering the world stage at a time when energy markets are saturated with excess barrels of crude oil, and its market share is being actively challenged by neighbors hostile to its prosperity.

Trapped funds. With the lifting of sanctions, Iran now has access to between $50 and $100 billion dollars of oil revenue in various banks around the world that was previously blocked. The question that has troubled those opposed to the nuclear deal is what Iran will do with these funds now that it has access to them. Will it use the money to rebuild its own economy?

The injection of such a large sum of liquidity directly into the Iranian economy would no doubt spark inflation, something the Rouhani administration successfully tamed and doesn’t want to revisit. Fortunately, Iran’s Vice President Mohammad-Bagher Nobakht has indicated that Iran will take the prudent course of action and keep most of these funds abroad in foreign banks in order to support Iranian companies looking to engage in international trade. It will do this by taking local currency from Iranian companies inside the country in return for opening letters of credit with foreign banks abroad and paying creditors with foreign currency. This prescription should jump start Iran’s trade with its European and Asian partners.

Energy investment. So much of the Rouhani administration’s economic plan to stimulate growth depends on foreign direct investment and the hope that now that sanctions are lifted, foreign firms will flock to the Iranian market. Iran’s energy sector is where foreign investment will most likely begin. According to Oil Minister Bijan Namdar Zangeneh, Iran needs between $150 billion and $200 billion dollars of capital investment to revitalize its antiquated energy infrastructure.

Before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran produced close to six million barrels of crude oil a day. Today it is producing less than half of that. With energy prices at lows not seen in a decade, and the world swimming in excess barrels of crude, Western oil giants will be reluctant to enter a frontier market when they are cutting spending on existing projects and watching their profits dwindle. Thus, Iran must weather this storm and prepare itself for the day when oil prices are more robust and the Western oil companies are jockeying for access to a country with the fourth-largest proven reserves in the world. To that end, Iran has taken a major step in the right direction by instituting a new contract scheme—the Iran Petroleum Contract (IPC). The IPC will allow foreign companies to become joint venture partners with the state-owned National Iranian Oil Company, rather than contractors, which was their status under the much-maligned buy-back scheme of the last two decades. Absent the nuclear deal, it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which the government would have taken such a major step to lure foreign companies by offering better commercial terms.

Finance and banking. Perhaps no segment of Iran’s economy will feel the benefits of the nuclear deal as strongly as its banking sector. For the past three years, Iranian banks have been cut off from SWIFT, a Belgium-based financial clearing and communication network that is used by international banks for fund transfers. This, coupled with sanctions on Iran’s central bank, crippled the country’s financial sector, blocking access to hard currency and making it difficult to conduct trade. Now that these sanctions have been removed, banks in the European Union are allowed, once again, to transfer funds to and from Iranian banks.

However, difficult hurdles remain. The United States maintains non-nuclear-related sanctions on Iran and therefore American banks must continue to steer clear of all Iran-related commerce. Over the past decade, the US Treasury has levied heavy fines on European banks such as HSBC, BNP Paribas and Standard Charter for violating US sanctions on Iran. This has caused a chilling effect among Europe’s largest banks, which so far have decided to steer clear of Iran because of the regulatory and legal headaches that could complicate their existing business in the United States—the world’s largest economy. Iran can expect this void to be filled by smaller, more nimble European banks with a larger appetite for risk and not much exposure to the US market. While not ideal for Iran, this is a step up from where it was before the nuclear deal.

Sanctions have a silver lining. There is no doubt that sanctions have made the Iranian economy more resilient by forcing it to develop its own industrial base and reduce its dependence on crude oil exports. Today, energy exports account for only 15 percent of Iran’s GDP, compared to 55 percent for Saudi Arabia. In 2015, the Iranian government received more in tax revenue than oil revenue. Iran has the potential for robust growth, should President Rouhani be able to deliver on his plans to rein in corruption and liberalize large sections of the Iranian economy that have traditionally been under state control. If he does, the nuclear deal will continue to pay dividends.

This is not to say that all is rosy in Tehran. Despite the nuclear accord and recent election victory of centrist politicians, there are elements of the Iranian deep state that are extremely hostile to Rouhani’s agenda. They don’t want to see the country’s economy open up, or the people have greater connectivity to the outside world. Rouhani and his supporters will have to proceed with great care.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Weapons