Just 90 companies are accountable for more than 60 percent of greenhouse gases

By Dan Drollette Jr | October 27, 2016

There’s a tendency to think that when it comes to climate change, we’re all equally at fault—and if everyone is to blame, then no one is to blame. But now it’s possible to identify the contributions of individual companies, thanks to the work of researchers such as Richard Heede. What he found is revealing: A handful of companies bear a lot more responsibility for climate change than others, having pumped much more carbon into the atmosphere.

And Heede proved this by spending nearly 12 years collecting and analyzing data from a variety of publicly available sources, pinning down which companies have contributed what percentage of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution—and then named names. Sometimes working alone for long periods while squirreled away in a houseboat on San Francisco Bay, Heede laboriously put together a sort of enormous jigsaw puzzle of facts, painstakingly chasing down obscure skeins of data to come up with the big picture.

Some of the results were astonishing, such as that the number of companies responsible for the majority of the carbon in the atmosphere was so small that “[Y]ou could take all the decision-makers and CEOs of these companies and fit them on a couple of Greyhound buses.” He’s found that although there are thousands of oil, gas, and coal producers around the world, just 90 entities are responsible for 63 percent of all the industrially produced carbon dioxide and methane being emitted into our atmosphere.

And nearly half of that carbon was pumped into our atmosphere in just the past 30 years.

The Bulletin’s Dan Drollette caught up with Heede by phone in this interview. (Editor’s note: This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

BAS: How to best summarize your work in a sentence or two? Is it fair to describe you as a sort of carbon accountant or carbon detective—someone who has compiled a massive database that puts numbers to those most responsible for taking carbon out of the ground and pumping it into the atmosphere?

Heede: Well, I quantify and trace the emissions in fossil fuels by each year, by each company, by fuel. I then estimate how much carbon from their annual production ends up in the atmosphere, allowing for non-energy uses of liquid fuels such as using oil for making asphalt, or using petrochemicals to making plastics and clothing. With that information, we can estimate how much of the carbon each company produces each year ends up in the air.

BAS: An article about your work was titled “Just 90 companies are to blame for most climate change.”

Heede: Well, yes … but I would say that there are actually more like 83 companies that are responsible for the bulk of climate change, plus seven countries for which we didn’t have any corporate data—for things such as Chinese, Polish, and North Korean coal production, for example. I called these companies and countries the “carbon majors” in my paper for Climactic Change. But our focus was really on the corporate sector, whether it be state-owned oil companies—such as those in Saudi Arabia, Norway, Venezuela, to name a few—or investor-owned companies.

I do this in part by drawing upon a corporate history we have built of fossil fuel production converted to carbon dioxide emissions by consumers who buy the products that ExxonMobil, Chevron, and everybody else distributes and markets.

Obviously, the focus was on oil, gas, and coal companies, but we also included six cement companies.

BAS: Cement companies?

Heede: Oh yes, definitely. Their emissions were certainly large enough to meet the minimum threshold to be included in our study, which was 8 million tons of carbon per year.

BAS: How do cement-makers pump carbon into the atmosphere?

Heede: In the industrial cement-making process, you heat calcium carbonate to make cement, which drives off carbon dioxide as an industrial waste product. And I’m only counting the carbon that is driven off in the cement-making process as an industrial waste product; that’s not including the considerable energy input it takes to get and keep the kilns hot enough to make cement, whether it be the burning of coal or tires or the use of electricity or what have you to create the heat.

The cement-making companies contribute a significant amount. I forget the exact ratio but it’s about a ton of CO2 for each ton of cement. And they’re making millions of tons of cement per year, so you’re obviously talking about cement-making companies producing millions of tons of carbon. Globally, the cement companies account for 3-to-4 percent of global industrial emissions.

BAS: Tell us a little more about what these percentages mean.

Heede: When I say that historically, Chevron is responsible for 3.69 percent of global industrial emissions of CO2 since 1751, I am comparing Chevron’s total historic emissions to the total global emissions of all fossil fuels since 1751.

I do this in part by using a database of all industrial emissions—national emissions from fossil fuels and cement—compiled by Oak Ridge National Laboratory that goes back to 1751. This database excludes deforestation and land use and other anthropogenic sources, so it only looks at the CO2 pumped into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels and the creation of cement. Those two activities make up the majority of all the greenhouse gases created by human activity, but are by no means all of it. There’s landfill methane, for instance, which is not included in these figures.

So when I give a percentage that compares the emissions of a company like Chevron, for example, to global historic emissions since 1751, that’s what I’m talking about: Chevron’s historic emissions compared to this Oak Ridge database of all historic global emissions.

And we chose the 1750s because that’s pretty much the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, when all coal production was pretty much confined to England and Germany.

Incidentally, things have accelerated greatly since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Half of all the CO2 emissions in the industrial sector from fossil fuel and cement use have come since 1988.

BAS: In other words, using this information, you found that only 83 companies and 7 countries are responsible for the majority of the carbon in the atmosphere—and most of that was in the last three decades?

Heede: Correct. Of all global emissions from fossil fuels and cement since 1750, half have occurred since 1986. Things are accelerating.

BAS: Is there one company in particular that really stands out, head and shoulders above the rest?

Heede: No one company stands out, as the largest emitters are each responsible for something in the range of around 4 percent or more of CO2 emissions. Saudi Aramco is up in that range, as is Chevron, ExxonMobil, Gazprom, and BP. Chinese coal production is also high. But not one entity all by itself; instead it’s 90 entities.

BAS: Did you really tell The Guardian newspaper that “you could take all the decision-makers and CEOs of these companies and fit them on a couple of Greyhound buses”?

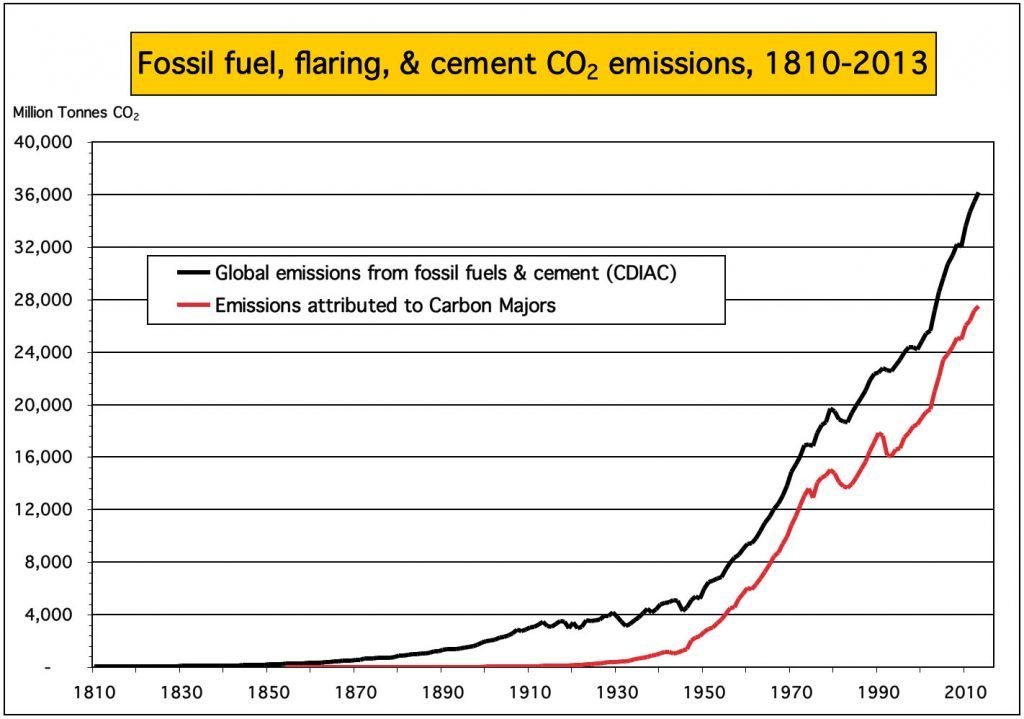

Heede: Yes. The whole thing is pretty startling. The black line in that figure I drew up shows all the total global, human-made emissions from fossil fuels and cement. It starts with the year 1810, because things were basically zero prior to that. In fact, the lines on the graph only really start to move upward around 1850.

The red line is everything that I have collected and chased back to the individual companies and the seven countries that I have mentioned, year by year. So it shows the majority of all emissions, historically. The proportionate contribution from each one does vary from year to year.

BAS: How did you even collect the information about the emissions contributions of individual companies? For instance, how do you know how much oil Chevron, for example, produced over the years?

Heede: Well, in recent years, it helped me a lot once the annual reports of companies were digitized; the information became more readily available.

Do you want me to tell more about the process of how I collected the information on the emissions from the individual companies?

BAS: Sure.

Heede: First, you need some background. My friend Peter Roderick had started a project in London called the Climate Justice Program, with funding from Friends of the Earth and others in Europe, whose goal was to study the atmospheric CO2 contributions of one particular oil company over history: ExxonMobil. We wanted to go all the way back to when the company was first started—it was known as Standard Oil back when John D. Rockefeller founded it in 1882—and estimate its emissions in a formal manner. He found me through a mutual colleague, and enlisted me in the project. That was in 2004.

After 15 months of research, we concluded that globally, ExxonMobil and its precursors was responsible for directly or indirectly emitting 20.3 billion metric tons of CO2 and 199 million metric tons of methane, or between 4.7 percent and 5.3 percent of all of humanity’s industrial greenhouse gas emissions since 1882.

After publishing that information, we wanted to expand the work and look at more companies, by type and by fuel. To be on the list, each company had to contribute at least 8 million metric tons of carbon per year—that 83 company figure I mentioned. We then went back and with the help of volunteers located in libraries around the world—in Sydney, New York, Johannesburg, London, Berkeley, and elsewhere—and found annual reports for each of these companies. And each annual report contained data on all of the company’s fossil fuel production for a given year. The volunteers then made photocopies and sent me paper copies of the relevant production tables from the reports, so I now had a vast library of photocopies of fossil fuel production, by company, by year.

I should add that we weren’t always able to get annual reports for every company every year, because most companies didn’t start publishing annual reports until the US Securities and Exchange Commission started to require them to do so in 1933.

Then myself, with various assistants over the years, entered the production figures per year in Excel worksheets, and developed the methodology for estimating the amount of carbon subsequently released into the atmosphere. And then basically computed each company’s emissions by year, for all of these companies.

After many misadventures and delays, we got all the information together and it was published digitally in November 2013.

BAS: Were you surprised by what you found?

Heede: It seemed evident to me that this would happen, so I cannot say that I was completely surprised. But no one knew the exact proportion of their contributions until now. And it’s important to have a very robust estimate of the percentage contributions of each company to greenhouse gases.

Now, I want to point out that we are not saying that this small number of entities is totally responsible for all the greenhouse gases causing climate change. But they are responsible for a major proportion.

They are responsible in two ways—they were behind the pumping of this carbon into the atmosphere.

And they promoted the denial of the scientific evidence for climate change. Instead of following the science, and understanding the nature of climate change and their own companies’ contribution to it, they tried to suppress it. They didn’t enter an open debate with the public; instead of being open to discussion, they decided to instead enter into obfuscation and denial.

BAS: Carroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environmental Law in Washington, D.C., said: “For decades there’s been a persistent myth that everyone is responsible, and if everyone is responsible then no one is responsible… Rick’s work for the first time identifies a discrete class of defendants …”

Heede: Yes, I was pleased to read that.

And I agree, but I want to point out that my focus on attributing responsibility to carbon producers is that they need to share and accept responsibility, not that they are solely responsible, or that consumers and individuals have none.

BAS: Does that mean that lawsuits are a possibility?

Heede: I suppose that that implication is being considered, but I’m purely an independent scientist. I’m happy to provide quantitative data to anyone who asks, including the International Committee on Human Rights. It is definitely being explored, by people such as the state attorney general of Massachusetts, Martha Healey, and state attorney general Eric Schneiderman of New York.

BAS: Speaking about your work as an independent scientist, I understand that you wound up doing much of the heavy lifting on your own, without the support of a full-time position at an academic institution or think tank, is that right? And that it took eight years to do?

Heede: Twelve years.

BAS: I want to read aloud an excerpt of an article about your work, from the journal Science: “Heede takes me on a tour of his data set, a seemingly endless series of color-coded and cross-indexed spreadsheets. Each sheet lists hundreds of entries, with columns showing the year and total production volumes for products such as crude oil, natural gas, and varieties of coal. Clicking on a company’s name opens additional spreadsheets with the company’s year-by-year production, plus screenshots of its annual reports for verification. Color-coded flowcharts display the evolution of companies as they separated or merged. The flowcharts from Russia are particularly ornate, as they incorporate the transformation of companies after the fall of the Soviet Union. (Heede got production data for the Soviet companies from Central Intelligence Agency analyses and the International Energy Agency.) Detailed annotations reveal his methods and calculations. The structure of these charts, so layered and interlocking, seems almost medieval in its complexity, and Heede seems monk-like in his devotion to compiling it.”

Heede: I have a native careful, meticulous, and detail-oriented nature. I pay attention to detail and I want to get things right—that’s what’s necessary to engage in this long-term, detailed work. I’m hoping it will lead to effective action by oil, gas, and coal companies in the coming years, and rescue us from the damage that will be coming from climate change.

To their credit, most oil companies are now no longer fighting the science. At least that’s some kind of progress. But now, they need to understand that they have responsibility for their products.

BAS: Your written comments about the oil industry seem to reveal a grudging admiration for what they do.

Heede: I don’t know about grudging, but the fossil fuel industry has done amazing work, in extreme and harsh environments, often deep underground. They’ve made fantastic efforts to find resources that made life easier for much of humanity. And they’ve done such a good job that we simply have not stopped to pause and reflect on the unintended consequences.

BAS: Are there any parallels to what happened with chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—the stuff that caused the holes in the ozone layer—and the companies that produced them?

Heede: In the case of CFCs, the companies that made them had a viable commercial opportunity to produce an alternative. And they stepped up to the plate. That’s not as obvious with fossil fuels.

I think a better parallel with the current state of the fossil fuel industry is that they are more like the tobacco companies when it came to the evidence for the link between smoking and cancer. They didn’t see a commercial alternative, and saw any form of regulation as a threat to their business. They did not have the moral fortitude to deal with it. It was easier to obfuscate, deny, and delay.

The oil companies need to recognize that they cannot go on with business as usual; they cannot continue to find and develop new oil fields or get into things like oil sands, which are the most carbon-intensive activity out there. They don’t want to wind up with a whole lot of money tied up in assets that they cannot use—that’s a huge risk for their shareholders. They need to shift now, to other ways of doing business.

The largest companies spend tens of billions of dollars in acquiring new reserves. At some point, they will have to assess if their reserves will be stranded. The companies that win will be the ones that understand that they have to invest in low- and zero-carbon energy forms. They have decisions to make about the best use of their investments.

BAS: What do you think is the take-away from your work?

Heede: Energy efficiency is far cheaper per unit than adding generating capacity. We need to pay attention to that, through technology and behavior. And we should be able to find the money to do that; after all, if we can subsidize fossil fuel discovery and development to increase supply, then we can spend money on reducing demand. With that in mind, regulation is important.

It’s what these companies do henceforth that matters. Do they keep their head in the oil sand and fight change, or do they understand that embracing climate stewardship gets loyalty from their customers?

And on a related note, you and I may not be carbon majors, but we need to do our part, too, in saving fuel and behaving responsibly. That’s one reason I have built a passive-solar, rammed-earth house that emits approximately 3-to-4 pounds of carbon dioxide per square foot per year, or about 75 percent less than the average single family home. And it’s why I drive far less than average, and modify my life to respect my own science-based limits on carbon emissions.

But, hey, I fly a bunch, and am about to hit the beach in November. Zero carbon is not yet possible, and we can still enjoy life. The objective is shared responsibility and action, not reverting to the Stone Age, as our critics falsely attribute to us.

BAS: What are you working on now?

Heede: I want to quantify the potential carbon release from future fossil fuel exploration.

BAS: How did you become interested in this research in the first place?

Heede: I had started out in environmental studies, and spent the first few years out of college looking at biodiversity loss, energy systems, and environmental impact. I worked for Amory Lovins’ Rocky Mountain Institute, and before that I had read an early, 1970 MIT report that affected me deeply, called Man’s Impact on the Global Environment—it was one of the earliest publications to bring up the possible effects of increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

But going farther back, I was born in Norway in 1952—long before the North Sea oilfields were discovered, so there was no cause-and-effect—and spent much of my early years there, before we moved away when I was a teenager. So I grew up in the natural environment of Norway with a spirit of exploration, a love of that harsh, beautiful area, and a respect for the single most beautiful planet ever seen.

(Global industrial emissions data in Figure 1 courtesy of Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, plus methane information from Stern & Kaufmann & European Commission [black line]. Results of all Carbon Major entities’ emissions of CO2 and methane [red line] and graph itself courtesy of Richard Heede.)

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Climate Change

greenhouse gases have a great influence over the enivironmental issues. major effects like global warming, ozone depletion and much more…