Women and the ban the bomb movement

By Ray Acheson | June 15, 2017

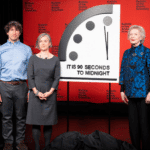

This week at the United Nations in New York City, governments, international organizations and civil society groups are gathering to resume negotiations on a treaty banning nuclear weapons. And women are at the forefront of this effort—as they have been at the forefront of the anti-nuclear resistance since the beginning of the nuclear age.

The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) —where I work as director—was one of the first civil society groups to condemn the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (The term “civil society” gets used a lot and has many different definitions, but is generally accepted to mean groups working in the interests of citizens but outside of government or business; some examples include charities and non-governmental organizations such as the Red Cross.) Women were leaders in the campaign to ban nuclear weapon testing in the United States, using powerful symbols such as a collection of baby teeth to show evidence of radioactive contamination. Women led the Nuclear Freeze movement in the 1980s, calling on the Soviet Union and the United States to stop the arms race. Now, women are the leading edge of the movement to ban nuclear weapons in the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.

When the three-week-long negotiations at the UN resume on June 15, women will be continuing this tradition, both in the conference room and on the streets. As part of its efforts to ban nuclear weapons, the WILPF is organizing the Women’s March to Ban the Bomb, on June 17, to be held in mid-town Manhattan. Other events will be held across the globe to show solidarity with the march, in places as far apart as Australia and Scotland. The event has over 30 sponsors and endorsers from around the world.

In my opinion, the process of banning nuclear weapons serves another purpose as well: It acts as a challenge to much of the existing discourse, which has been distinctly patriarchal in tone.

In fact, much of the opposition to the nuclear ban process has been highly gendered. Those who talk about the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons and call for the prohibition of weapons of mass destruction are accused of being divisive, polarizing, ignorant, and emotional. Meanwhile, opponents to the ban say that they support “reasonable,” “realistic,” “practical” or “pragmatic” steps, and call anything else “irrational” and “irresponsible.”

Many women may recognize this rhetorical assault. When a certain type of man—think Donald Trump—wants to assert his power and dominance and make women (or other men) feel small and marginalized, he often accuses them of being emotional, overwrought, relentless, repetitive, or irrational. This technique has been employed for as long as gender hierarchies have existed.

In the case of the ban treaty, this approach links caring about humanitarian concerns to being weak, and asserts that “real men” have to “protect” their countries. It not only suggests that caring about the use of nuclear weapons is spineless and silly, but also implies that the pursuit of disarmament is an unrealistic, irrational, and even effeminate objective.

Of course, the fact that masculinity is equated across so many cultures with the willingness to use force and violence is a social phenomenon, not a biological one. Boys come to learn to define themselves as men through violence. The way that norms of masculinity such as toughness, strength, and bravado are displayed in the media, at home, and in school teaches boys to exercise dominance through violent acts. Boys learn to think of violence as a form of communication.

Nuclear weapons are themselves loaded with symbolism—of potency, protection and the power to “deter” through material “strength.” For many, such symbolism obscures the real point of the existence of these arms—to destroy—and their horrendous effects.

Nuclear weapons are not just symbolically gendered. Women face unique devastation from the effects of the use of nuclear weapons, such as the impacts of radiation on their reproductive and maternal health. Women who have survived these radioactive effects also face unique social challenges; they are often treated as pariahs in their communities.

Consequently, denying the rationality of those that support a nuclear weapons ban is also a denying of the lived experience of everyone who has ever suffered from the use or testing of nuclear weapons.

This is why it’s essential to ensure gender diversity in negotiations, and why it’s important to include a gender perspective in those negotiations. To celebrate the nuclear ban—and women’s leadership in achieving it—there will be the Women’s March to Ban the Bomb.

This post is part of Ban Brief, a series of updates on the historic 2017 negotiations to create a treaty banning nuclear weapons. Ban Brief is written by Tim Wright, Asia-Pacific director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, and Ray Acheson, director of Reaching Critical Will.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Announcement