Hibakusha, the ban treaty, and future generations

By Masako Toki | August 10, 2017

Around this time every year, we have an opportunity to learn more about—and reflect upon—what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki when atomic bombs were dropped on these cities.

The peace declaration read by Hiroshima’s mayor, Kazumi Matsui, at this year’s peace ceremony illustrated the horror of a single nuclear weapon that killed over 140,000 people. He depicted an “absolute evil” that was “unleashed in the sky over Hiroshima,” and implored the audience to “imagine for a moment what happened under that roiling mushroom cloud.”

It was a very poignant moment.

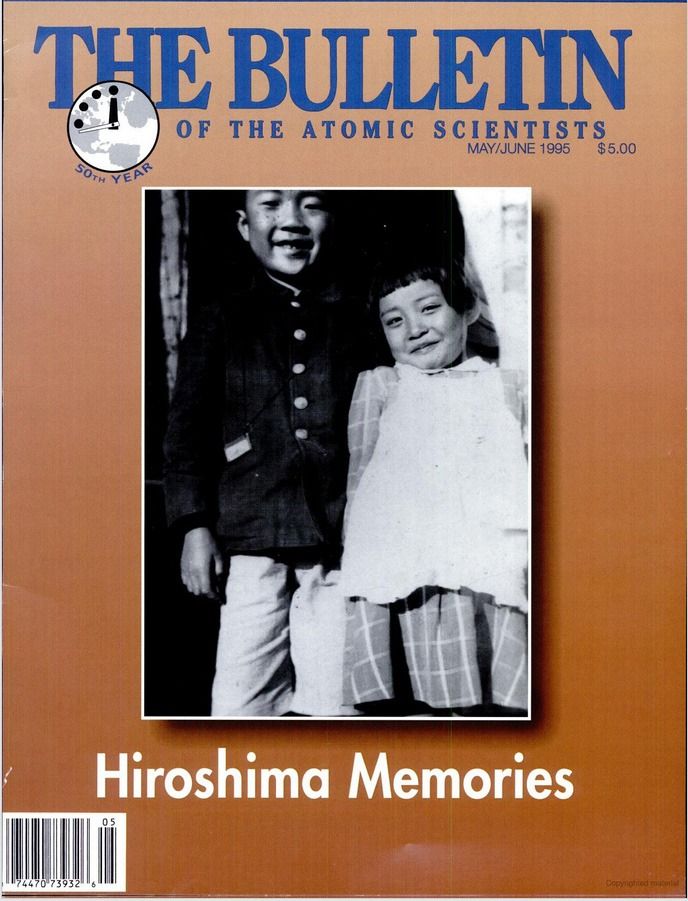

But I think that an even more compelling way to understand what really happened on that day is to listen to the recollections of the atomic bomb survivors, or Hibakusha, in their own words. These first-person accounts can deliver a sharp, keen sense of the effects of a nuclear bomb’s detonation, as portrayed in autobiographical books such as Hiroshima Memories, whose author, Hideko Tamura Friedman, was just a young girl when the bomb was dropped on her hometown on August 6, 1945. In an understated, matter-of-fact tone that makes the tale even more powerful, Hideko details the events of that day—such as how she was lying in bed reading a book early in the morning when “a huge band of white light fell from the sky down to the trees.” She jumped up and hid behind a large pillar as an explosion shook the earth and pieces of the roof fell about her. Hideko survived; some other members of her family did not. “My father,” she wrote in a heart-rending statement of fact, “brought Mama’s ashes home in his army handkerchief.”

Such direct, immediate, first-person accounts fill the gap in historical renderings of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and help to give a clearer understanding of the actual effects of the use of nuclear weapons against human beings. The Hibakusha recollections help to demystify nuclear weapons, and remove any euphoria or sanitization about the use of atomic bombs.

Unfortunately, it is inevitable that one day there will be a world without any Hibakusha to tell us these accounts. And that time is fast approaching. Currently, the age of the average Hibakusha is more than 81. Consequently, now is the time to teach the next generation about the very real effects of the use of nuclear weapons, and how to prevent these weapons from ever being used again.

Given their advanced age, it is unlikely that a world without nuclear weapons will become a reality in the Hibakusha’s lifetimes. However, through their long-term, tenacious efforts—as well as those of like-minded governments, international groups, non-governmental organizations, and other forms of what is termed civil society—an important breakthrough did emerge recently in nuclear disarmament.

The successful adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Nuclear Ban Treaty, on July 7 is one of the most significant developments in nuclear politics since the end of the Cold War. The treaty was adopted by a vote of 122 in favor to one against (the Netherlands), with one abstention (Singapore).

While the states possessing nuclear weapons made it very clear that they will never join the treaty (and the states under the protection of their nuclear umbrellas are likely to follow suit), this is still an historic event in the nuclear disarmament movement. The ban’s passage will help to stigmatize nuclear weapons, and by doing so, help to strengthen the norms against their very existence. Despite their indiscriminate and catastrophic humanitarian and environmental effects, nuclear weapons are the only weapons of mass destruction that have not yet been explicitly prohibited under international law. But after it is entered into force, this treaty would prohibit states from developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using, or threatening to use nuclear weapons. Years of effort to draw attention to the impact of nuclear weapons upon human welfare culminated in the adoption of the treaty.

Consequently, the significance of the impact of this treaty cannot be underestimated; as Setsuko Thurlow, one of the most vocal Hibakusha attending the Nuclear Ban Treaty negotiations, put it: “Nuclear weapons have always been immoral. Now they are also illegal.”

The Ban Treaty: just a first step. But even if “this is the beginning of the end of nuclear weapons,” as Thurlow claimed in the same closing statement, there is still an enormous task ahead of us.

Opponents of the Nuclear Ban Treaty—including nuclear-armed states and allies under their extended nuclear deterrence—not only boycotted the negotiations (with the exception of the Netherlands) but also criticized the treaty for deepening the division between nuclear weapons states and non-nuclear weapons states. These nuclear-armed states—especially the United States, the United Kingdom, and France—indicated no willingness to join the treaty. In fact, in their joint statement they reiterated their position that they do not “intend to sign, ratify or ever become party to it.” They asserted that the Ban Treaty “clearly disregards the realities of the international security environment.”

The Japanese delegate concurred, arguing that efforts to enact a nuclear ban treaty without engaging the countries that already possess nuclear weapons would only deepen the schism and delay the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons. Japan’s decision not to participate in the negotiations generated tremendous disappointments both outside and inside Japan, and especially among the Hibakusha. Many believe that Japan, as the only country to have suffered the effects of the use of nuclear bombs in wartime, has a moral responsibility to lead efforts to create a world without nuclear weapons. Japan’s government surely must have experienced a tremendous dilemma to come to this decision, knowing the extremely strong anti-nuclear weapons sentiment among its people.

This sentiment was articulated most clearly by Toshiki Fujimori, a survivor of atomic bombs himself, as well as a leader in the Japan Confederation of Atomic and Hydrogen Bomb Sufferers Organizations. Fujimori expressed the feelings of many Japanese people, when he said: “As a Hibakusha, and as a Japanese, I am here today heartbroken. Yet, I am not discouraged.”

What happens next? Japan continues to hope to be a bridge-builder for nuclear disarmament, uniting the international community in making progress toward a world free of nuclear weapons—a position which I argued for in a previous Bulletin article. By boycotting the ban treaty negotiation entirely, however, Japan degraded its credentials as a disarmament champion, and even as a bridge-builder.

This is especially ironic in light of the fact that the Japanese government had recently launched a new initiative called “the Group of Eminent Persons,” which sought to encourage dialogue between states armed with nuclear weapons and those without—or between “haves” and “have nots.” In his final appearance as Japan’s foreign minister, Fumio Kishida had told the preparatory committee of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty that Japan would host a meeting of experts from both nuclear and non-nuclear weapon states before the end of 2017 to discuss nuclear disarmament. And more recently, the Japanese government had announced its final selections for this group, including individuals from Japan, America, France, Russia, Australia, Canada, China, New Zealand, Germany, and Egypt. All are truly eminent, respected, thoughtful scholars, including former governmental officials and high-ranking officials at international organizations; the group includes people who both support and oppose the Ban Treaty.

But by boycotting the ban treaty negotiations, Japan has undone much of the goodwill this project might have built, leading to an inescapable sense of stagnation in nuclear disarmament on a deeper level. To achieve a breakthrough, it is essential to establish much stronger norms against nuclear weapons—not only in their use, but also in the mere possession of nuclear weapons.

One way to reach this goal might be through influencing future generations—which is where the memories of the Hibakusha play a vital role in reminding the young of the urgency of the cause, and the consequences if we fail to rein in the nuclear horror. In that area, one of the Japanese government’s initiatives, “Youth Communicator for a World Free of Nuclear Weapons” launched in 2010, is highly praiseworthy.

Cause for hope. And the young of Hiroshima seem to take this message to heart. At the recent Hiroshima peace ceremony, two elementary school students read a Peace Pledge which resonated in many people’s hearts. The statement highlighted the tremendous perseverance and effort undertaken by the people of Hiroshima to rebuild their city and overcome their indescribable ordeal. It also stressed the importance of continuing the effort to convey the sanctity of human life.

The rather short statement read by these future leaders epitomized the important task we have to pursue. To accomplish the goals of peace and security in a world free of nuclear weapons, we all need to overcome the tendency in our mindset to keep with the status quo.

The world nuclear situation is more dangerous than ever, as can be seen by recent news events. As a consequence, education about disarmament and nonproliferation has become more important than ever.

As a strong believer in the power of education for making progress toward a nuclear weapons-free world, I have been organizing a disarmament and nonproliferation learning program for high school students around the world. When William Perry, former US Secretary of Defense, gave a keynote lecture at our conference last year in Monterey, his assertion encouraged all the participants. He said: “I have believed for many years now that the only way I would want to deal with this nuclear problem is through education. And the education has to start young, at high school. I do not believe we will really deal effectively with the nuclear problem until the youth of our country become fully understanding about how dangerous this is to their future, and start to work actively to reduce this danger and to eliminate it.”

This year, we held a conference in Nagasaki to strengthen our determination to assure that Nagasaki would be the last city to experience nuclear devastation. High School students from the United States and Russia joined Japanese students in Nagasaki. These future leaders learned many important things from the Hibakusha of Nagasaki, who had experienced the horror of nuclear weapons first-hand, and endured unspeakable ordeals. There are many obstacles to overcome to make sure that nuclear weapons will never be used again. But with the aid of the Hibakusha, the ban treaty, and civil society, today’s youth will have some of the key tools needed to break through the current stagnation in progressing towards nuclear disarmament.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]