Parmanu: India’s first nuclear film

By Karthika Sasikumar | June 18, 2018

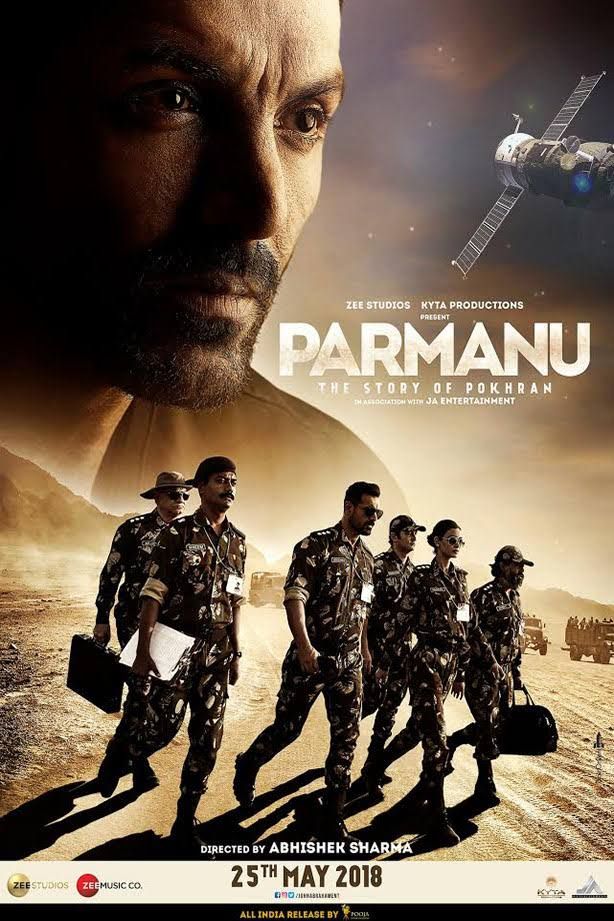

One of the posters for the new film Parmanu: The Story of Pokhran features a satellite in the sky, and a group of army officers on desert sand. Looming over both is the face of John Abraham, the actor who plays Ashwath Raina, the fictional architect of India’s 1998 nuclear tests. Abraham’s serious visage and piercing eyes confront the satellite, willing it to fail. The outsmarting of American satellite surveillance is at the core of this Bollywood take on the blast that kicked in the door of the nuclear club. Parmanu, which means “atom” in Hindi, tells us less about the reasoning that led to the tests, and more about India’s perceived antagonists.

It is no coincidence that the film starts off by pointing the finger at China, just as Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s (famously “leaked”) letter to US President Bill Clinton did. The first scene uses stock footage of a nuclear blast, complete with mushroom cloud, and the film identifies this as a 1995 test by China. For the rest of the film, China is not mentioned. Enough said.

The film’s plot. Released on May 25, Parmanu revolves around the character of Ashwath Raina, an officer from the Indian Administrative Service. The son of an Army officer, he wants to serve his country but flat feet deny him entry into the military. Raina comes up with a plan to conduct nuclear tests, in a way that preparations would be undetectable by the United States. His stated rationale is deterrence, expressed in two brief sentences. In 1995, his instructions are ignored, and India starts preparations for testing without the right precautions. The test has to be aborted, because the United States intervenes.

Raina is then sent into political exile. When the Bharatiya Janata Party government comes to power in 1998, he is rehabilitated by the Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister. Raina assembles a team of five individuals from different state agencies: the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, the Defence Research and Development Organization, the Army, the Research and Analysis Wing (India’s external intelligence agency), and the “Indian Space Agency” (as a civilian agency, the Indian Space Research Organization perhaps could not be named). The five team members are compared to the Pandavas in the Hindu epic The Mahabharata, with Raina playing the role of Krishna, the divine adviser to royalty. They work together to outwit the American Lacrosse satellites that periodically hover over the desert test site, Pokhran.

The film adds some drama by introducing interpersonal conflicts. The aristocratic Parsi scientist from the atomic research center butts heads with the stalwart Army major. The Defence Research and Development Organization representative is absent-minded and whiny, annoying the team. The man from the space agency is an overly bearded South Indian who cannot stop eating banana chips and other crunchy snacks. A dose of glamor is provided by the female super-spy from the Research and Analysis Wing. The enemy team consists of a CIA agent and his Pakistani Inter Services Intelligence sidekick, who are shockingly close. The enemy has satellite surveillance on its side; India has wisdom, as represented by Raina.

Raina’s plan is to use the spy satellites’ blind spots to prepare the ground for the tests. The preparations are done with military efficiency, and the CIA agent on the ground initially fails to convince Washington that the signals intelligence does not reveal the whole picture. Even when the CIA agent succeeds in calling for continuous satellite surveillance, Raina manages a feint. On his advice, the Indian government moves troops to the Line of Control, sparking fears of war with Pakistan. The United States then turns its attention (and its satellite surveillance) to the border regions, allowing the team in Pokhran to complete its preparations.

On the fateful day, the Prime Minister is closeted with the US Ambassador, but through yet another sleight of hand, the order to conduct the tests is procured and transmitted to Pokhran. The earth shakes, the Indian flag is hoisted, and the subtitles proclaim that the tests made India a nuclear state, its economy going into growth mode.

A narrow focus. Aside from the opening montage, which paints India in the mid-1990s as having lost its superpower friend (the Soviet Union) and as a target of one-sided treaties, the movie avoids discussing the larger political context of the tests. It prefers to focus on the drama of secrecy and the logistical race to the finish, which certainly make for better cinema. Parmanu pits Indian improvisation against the technologically sophisticated but lumbering hegemon in the form of the United States, and therein lies the core conflict. The Pakistani spy is indeed villainous, but also hapless (he threatens Raina with a loaded pistol, but the two tumble on the floor in the only physical confrontation of the film, as if the gun mattered not at all). Parmanu also does not mention India’s first nuclear test, conducted in 1974. Evidently, actual capability is not as significant as the country’s self-declaration as a nuclear weapon state—while 1974 was designated a “peaceful nuclear explosion,” India described the 1998 tests as weapon tests.

In the last minutes of Parmanu, we glimpse its philosophy. Raina tells his team not to worry about the outcome, but to strive to bring their plans to fruition. This narrow focus, on the immediate objective of carrying out the explosions, allows the film to indulge in jingoism without reflecting on its consequences. This inward focus is also reflected in Raina’s urging his team members to look at each other, rather than at the outside world’s reaction to India’s nuclear choice. There is only one instance when the dangers of a nuclear war are discussed. Halfway through the film, the scientist transferring the weapon cores to Pokhran mentions to his military escorts that the crates on the truck contain enough power to render the city of Mumbai underground.

Parmanu does not attempt to compete with the chest-thumping nationalist movies that Bollywood is increasingly producing. Its leading man is a manager, a logistics specialist, who harnesses the power of the state and technology. Its nationalism thrusts against an unfair world order without considering the repercussions for India’s own citizens. For instance, the film wants us to believe that deliberately stoking fears of war with Pakistan (which, like India in 1998, was capable of deploying nuclear weapons) was a legitimate and inspired move to facilitate the conduct of the tests.

There are plenty of unrealistic and false incidents in the film (such as the CIA officer galloping down the hallway to the President’s office as the test site was being readied), but they can be excused in the name of artistic license. The bigger issue is that Parmanu, India’s first nuclear movie, chooses not to ask the hard questions.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Opinion, Uncategorized