What if Iran leaves the NPT?

By Adam M. Scheinman | June 8, 2018

In apparent retaliation for the US decision to pull back from the Iran nuclear deal, Iranian officials warn that the country may withdraw from the landmark Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Whether Iran will or will not, or when and under what circumstances, are unknowns. It should be recognized, however, that Iran’s exit from the pact would be hugely damaging, stressing the global nonproliferation system to its limits.

Iran would not be the first country to withdraw from the NPT. That dubious distinction belongs to North Korea, which pulled out of the treaty in 2003 and of course went on to build nuclear weapons and intercontinental range missiles for their delivery. Yet, the effects of North Korea’s exit and strategic build-up are largely confined to East Asia and US interests in the Pacific.

South Korea and Japan may one day reassess the decision to forego nuclear weapons or to remain in the NPT, but that’s a longer-term risk given that both are US treaty allies and enjoy the protection of US military forces and nuclear umbrella.

Not to diminish the immensity of North Korea’s nuclear challenge, but Iran’s withdrawal from the NPT carries weightier risks. It would likely mean that Iran’s Supreme Leader had given the green light to an Iranian nuclear weapon, opening the floodgates to NPT withdrawals by other Arab states—Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt head that list. These and possibly other Sunni governments, none of whom can rely on a major power for defense, may conclude that they require their own nuclear weapon to check Iran’s rise. The Saudis are very clear and public on this point.

More immediately, Israel may feel compelled to strike Iranian nuclear facilities before they become fully operational. This raises the specter of a regional war that may draw in several of the nuclear weapon states—the United States, the UK, France, and Russia—and reshape the Middle East in ways we cannot predict. Whether the NPT could survive such a shock is another unknown.

Iran’s leaders are rational and surely understand the risk of events spinning out of control. For that reason alone, Iran is more likely to hedge for now on NPT withdrawal and avoid provocations that could either bring it to blows with the United States or provide the Europeans and others with a ready excuse to re-impose broad economic sanctions. Hardliners in Iran may believe the country can ride out sanctions without endangering the theocracy; moderates are less sure.

But hedging does not preclude bluster—a debating art form mastered by Iran—so one can expect from Iran a full-throated defense of its treaty right to withdraw. In this, Iran would be correct—but only to a point. Article X of the NPT says that a party may withdraw if it “decides that extraordinary events, related to the subject matter of this Treaty (emphasis added), have jeopardized its supreme national interests.” As described by two principal US negotiators of the NPT, the withdrawal right is not unconditional or a get-out-of-jail-free card. Given that the NPT’s purpose is to prohibit proliferation, Iran must demonstrate that its withdrawal is linked to a nuclear threat. It’s far from obvious how a US decision—whatever one thinks about it—to back away from the 2015 nuclear deal would constitute such a threat.

So what can be done if Iran defies predictions and decides tomorrow to exit the NPT? Our options may seem limited given European, Russian, and Chinese opposition to the president’s decision, but the cupboard isn’t entirely bare.

International law provides some remedy. For instance, it is a principle of customary international law that a state remains accountable for treaty violations that occurred prior to withdrawal. It’s worth recalling that questions about Iran’s past nuclear weapons work, which according to US intelligence estimates ended years prior to the 2015 nuclear deal, were never fully answered. Multiple UN Security Council resolutions sanctioned Iran for its failure to come clean on safeguards violations reported by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). So long as the nuclear deal was in place and enforced, those questions could be deferred. Ironically, if Iran retaliates by bolting from the NPT, then the known or imputed safeguards violations could return to center stage.

At the political level, the United States and willing partners could issue statements nationally or through the G7 and other bodies. The statements could challenge the legitimacy of withdrawal where the requirements of Article X are not met, call for extraordinary meetings of NPT parties to consider responses, and set the table for reopening Iran’s nuclear file at the UN Security Council and the IAEA’s Board of Governors. The latter is a must-do if Iran terminates its safeguards agreement with the IAEA, as it has a right to do, post-withdrawal.

As a further step, Russia and China could be encouraged to suspend all pending or future nuclear energy deals with Iran post-withdrawal. We could also pursue agreement in the 48-nation Nuclear Suppliers Group that nuclear exports previously licensed to Iran must remain under IAEA verification—even if a state exercises its NPT withdrawal right. These states could also insist that Iran return any supplied nuclear items, although it is hard to imagine how Iran could compelled to do so short of military force.

Tough, new UN Security Council actions in response to Iran’s withdrawal are probably not in the cards. For a variety of reasons, Russia and China are wary of using UN instruments to pressure Iran and cannot be counted on for support absent indisputable proof of an active bomb program (like a nuclear test).

Naturally, it would be useful if the international community came to agreement on responses before Iran withdraws. That might actually alter the regime’s calculus. While the United States would surely consult with allies and others on a collective response should withdrawal look imminent, gaining agreement among the wider NPT membership has its own set of challenges.

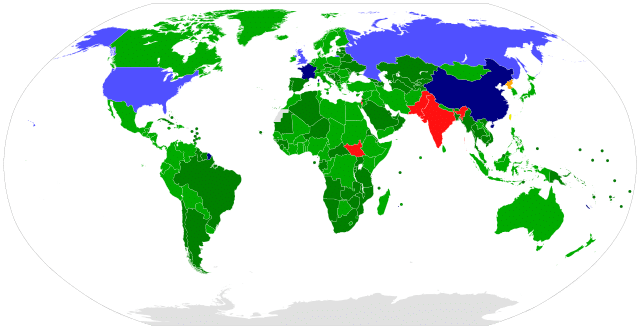

In the 15 years since North Korea announced its departure from the NPT, treaty parties have failed repeatedly to agree on ways to address this issue. Why? The foremost reason has to do with a zero-sum attitude that permeates NPT politics. Sensible actions to strengthen the nonproliferation aspects of the treaty, whether on withdrawal or verification, are held hostage to sought-after concessions on disarmament or other particular issues favored by groups of NPT parties. States are of course free to pursue their policy preferences. But it should be acknowledged that the problem is metastasizing in the NPT, and succeeds only in stalemating NPT meetings, deepening political divides among the parties and weakening the treaty at the moment it is needed most.

There is nothing to replace the NPT if it were to collapse. The new nuclear weapons “ban” treaty, despite the fantasies of some, is no functional substitute, not least because about a third of the world’s states reject it. One can hope that in this golden anniversary year of the NPT the parties will find ways to ensure it survives intact for another 50 years.

The international community could start that process now by taking a clear-eyed assessment of the dangers of NPT defections, most of all by Iran.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and are not an official policy or position of the National Defense University, the Defense Department, or the US government.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, The Iranian problem