Another chance to step up: Canada and the Nuclear Ban Treaty

By Laurélène Faye, M.V. Ramana | July 6, 2018

The "Peace Arch” monument marks the border between British Columbia and the state of Washington. Sited on the most direct automobile route between Vancouver and Seattle, the inscription on the US side reads "Children of a common mother," while the Canadian side says "Brethren dwelling together in unity." Another plaque reads: "May these gates never be closed." (Photo used under Wikimedia Creative Commons license.)

The "Peace Arch” monument marks the border between British Columbia and the state of Washington. Sited on the most direct automobile route between Vancouver and Seattle, the inscription on the US side reads "Children of a common mother," while the Canadian side says "Brethren dwelling together in unity." Another plaque reads: "May these gates never be closed." (Photo used under Wikimedia Creative Commons license.)

The recent G7 summit in Quebec marks one of the lowest points in the history of the relationship between Canada and the United States. The war of words there between President Donald Trump (and his advisers) on the one hand, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on the other, followed a growing disagreement over the terms of trade between the two countries that started with President Trump’s call to slap tariffs on imports of various goods from Canada. The dispute points to differences between Canada and the United States in the economic aspect of their relationship.

On the security front, however, there is a general perception that there is close, almost lock-step agreement between the two countries. Indeed, when members of the Trump administration suggested that the decision to impose tariffs was prompted by US national security concerns, there was widespread condemnation in the media—both in America and in Canada—with many commentators pointing out that Canada and the United States have an extraordinarily close security relationship. (After all, the two countries share the longest undefended border in the world.) Canada is a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance and has joined the United States in several military actions around the world for many decades, from Korea to Bosnia.

One illustration of this close relationship was on display last year when Canada refrained from participating in the negotiations that led to the Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear—also known as the Ban Treaty—was approved by 122 countries at the United Nations on July 7, 2017. Canada’s decision was evidently influenced by a October 2016 “non-paper” from the United States Mission to NATO which stated: “The United States calls on all allies and partners to vote against negotiations on a nuclear weapons treaty ban, not to merely abstain. In addition, if negotiations do commence, we ask allies and partners to refrain from joining them.” The decision by Canada’s government to follow this call and not participate in negotiations was widely condemned within the country, but others saw it as in line with Canada’s traditional position at the United Nations on nuclear weapon issues.

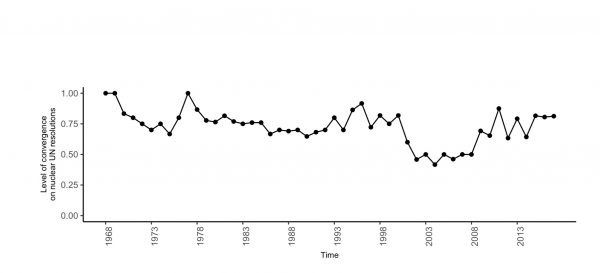

This widespread perception—that Canada and the United States agree on nuclear weapon issues—is partially true. But not always. Earlier this year, as part of a project on Canada’s position on the Ban Treaty, we conducted a careful review of how Canada has voted on United Nations resolutions dealing with nuclear weapons; Canada, it turns out, does not always march hand in hand with the United States when it comes to all things nuclear, and there have been significant divergences. Indeed, in the last 50 years, there have been only three years when Canada and the United States voted identically on all nuclear-related resolutions at the UN General Assembly, as shown in graph 1 below.

What is plotted is the level of convergence between Canada and the United States. We define the level of convergence as follows: On each resolution, when both countries vote the same way (yes, no, abstained), the level of convergence was taken to be 1. Similarly, if one country voted yes and the other voted no, the level of convergence was taken to be 0, while 0.5 was used for those resolutions where one country voted yes or no and the other abstained. For each year we averaged the level of convergence across all resolutions to come up with the number that was plotted on the y-axis. On average, the level of convergence is around 0.75, which means that typically there are at least a quarter of all the resolutions where the two countries vote differently.

Our analysis also shows that there is a similar pattern of fluctuating divergences between Canada and its two other close allies, France and the United Kingdom—both of which are also part of NATO and are nuclear weapons states.

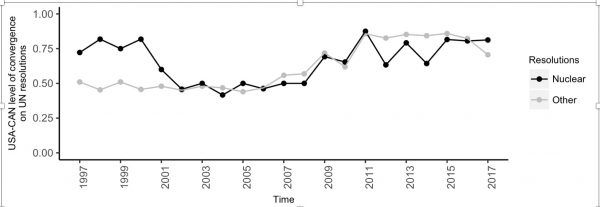

These divergences were not limited to the nuclear weapons arena. When it came to UN resolutions that called for ending the embargo against Cuba or offering assistance to Palestine refugees, to name just two issues that have come up over the past two decades, the United States and Canada significantly diverged in how they voted. Interestingly, the pattern of divergences on the other resolutions was not the same as the pattern on nuclear resolutions (see graph number 2 below).

Such differences cut across ruling parties in Canada and the United States. This is apparent from the graph above. Over the last 20 years, both the United States and Canada have had governments from the two major parties in each country. During this period we can see all the possible four combinations: Liberal – Democrat (1997 – 2000, 2016); Liberal – Republican (2001 – 2006, 2017); Conservative – Republican (2007 – 2008); Conservative – Democrat (2009 – 2015).

Digging deeper into these votes over the last 20 years, we noticed that there were specific resolutions that recurred over many years, where Canada consistently voted differently from the United States. A particularly important example is the resolution that called for the establishment of a nuclear-weapon-free southern hemisphere. This was first introduced in 1996 and received yes votes from 129 countries. Only the United States, France and the United Kingdom voted no. Thirty-eight countries abstained. This was by no means the only resolution where the two countries differed. Clearly, Canada doesn’t see eye-to-eye with the United States on several nuclear-related issues.

One possible interpretation might be that these votes were about minor resolutions. But the United States cared a lot about some of these resolutions, as can been seen by some US government statistics. (As required by law, US officials compile a list of “important UN General Assembly votes” every year. These are defined as “votes on issues which directly affected important United States interests and on which the United States lobbied extensively.”) There were at least two resolutions that were labeled as important votes where Canada voted yes even while the United States lobbied for a no vote.

One prominent non-nuclear example of a UN vote where Canada differed strongly from the United States was during the effort to ban landmines. As is well-known, Canada championed the Ottawa treaty that bans landmines. Although the United States never voted for the treaty, in 2014 the United States stopped using landmines, except in the Korean Peninsula, as a matter of policy. In other words, when the underlying principles behind treaties become so widely accepted as to be considered a norm, even non-signatories could start following those principles, at least for the most part. (This might well happen with the United States and the climate agreement signed in Paris, or so we hope.)

As with these examples, Canada could also diverge from the United States in how it acts on furthering nuclear disarmament. In October 2017, Prime Minister Trudeau stated that “We need to create a nuclear-free world for our children and grandchildren.” This goal remains distant and the “step-by-step approach” that Canada has followed so far has been unsuccessful and is likely to remain so.

But the Ban Treaty could offer a “historic turning point for disarmament.” Since its adoption on July 7, 2017, 59 countries have signed the treaty; 10 have ratified it as of a year later. The treaty will enter into force once 50 countries have ratified it. Canada should not wait for entry into force to sign the treaty.

Canada has a long history of being pro-active on seeking a world free of nuclear weapons. The current prime minister’s father, Pierre Trudeau, made great efforts towards disarmament diplomacy during his reign as prime minister in the 1970s. One of the leading opposition parties, Canada’s New Democratic Party, has strongly lobbied for the government to sign the Ban Treaty. Reducing the country’s reliance on nuclear weapons for security would certainly be in keeping with the feminist foreign policy that the current Prime Minister says he wants to develop, because nuclear weapons “have a disproportionate impact on women and girls,” as stated in the preamble to the Ban Treaty.

This history shows that there is a precedent for Canada to break with the United States on its policies towards nuclear weapons, and a compelling argument for Canada to do so: It would help to set the stage for reducing the reliance on nuclear weapons for global security. The current discord between Canada and the United States might just provide an opening for such a momentous step.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Canada, NATO, Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, UN General Assambly, ban treaty

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Opinion

Canada cannot sign the nuclear weapon ban treaty without at minimum changing its nuclear weapon policies and, because Canada is a NATO member, renouncing NATO deterrence doctrine. Otherwise Canada would be in violation at least of Article 1 (e) and (f) of the new treaty vis-à-vis its assist provisions. Article 1 Prohibitions 1. Each State Party undertakes never under any circumstances to: (e) Assist, encourage or induce, in any way, anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Treaty; (f) Seek or receive any assistance, in any way, from anyone to engage in any activity… Read more »

Robin and others

So, how did other NATO countries vote on the Ban Treaty in July 2017. Your message above implies that none of them should have voted for it either.

ELIZABETH, Yes, all NATO states voted against and my argument above applies to all of them. None can sign the ban treaty without renouncing NATO nuclear deterrence and placing obstacles in front of NATO nuclear policy, or else they will violate the treaty’s Article 1.