What the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots can learn from the antinuclear weapons movement

By Zoe Levornik | August 29, 2018

Peace campaigner Pat Arrowsmith (right), with a marcher holding one of the first signs depicting the Peace Symbol, during the seminal 1958 antinuclear march from London to the nuclear weapons facility at Aldermaston, UK. Image courtesy of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

Peace campaigner Pat Arrowsmith (right), with a marcher holding one of the first signs depicting the Peace Symbol, during the seminal 1958 antinuclear march from London to the nuclear weapons facility at Aldermaston, UK. Image courtesy of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

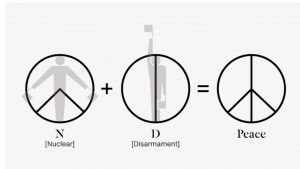

In 1958, a young British graphic artist named Gerald Holtom wanted to design a logo for a then-new, if still somewhat obscure, antinuclear weapons organization in the United Kingdom, called the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. The group’s leaders were planning one of the first major antinuclear marches in the country—from Trafalgar Square in London to the nation’s nuclear arsenal 50 miles away in Aldermaston—and needed an immediately recognizable symbol. Holtom took the semaphore letters N (for “nuclear”) and D (for “disarmament”) and combined them, then put a ring around the whole thing.

The result became wildly successful, it was free for anyone to use—it was intentionally never copyrighted, so no one has to pay or seek permission—and it became rapidly known worldwide, evolving beyond purely a symbol for this one march.

We in the United States call it the peace symbol.

Holtom later wrote of his creative process: “I was in despair. Deep despair. I drew myself: The representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad. I formalised the drawing into a line and put a circle round it.”

The symbol has remarkable staying power; just last month, design critic and cultural historian Stephen Bayley told CNN that he considered this graphic image to be “a minor masterpiece with major evocative power… All good graphic devices should be lucid and capable of applications in different media. But this one has the advantage of a nice semantic ambiguity: It can be read in different ways. A missile at lift-off? A person waving in despair? A Druidical reference? But it bypasses interpretation: It’s a thing unto itself.”

“It speaks very clearly of an era and a sensibility. It is, simply, a fine period piece: the ordinary thing done extraordinarily well.”

Why bring all this up?

Because the modern concern over the development and possible military use of autonomous weapons systems powered by artificial intelligence (AI) could learn much from the antinuclear weapons movement, when it comes to disseminating a message.

A problem in need of articulation. Several organizations, including the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots have been actively trying to raise awareness of the dangerous implications of these new technologies, and to the ethical and moral challenges we face in this new age.

The ICRC argues in favor of maintaining human control over weapons systems and the use of force, and the need to establish limits on autonomy in weapon systems. It argues that the decision to use force is legally and ethically a human responsibility; therefore, these decisions cannot be delegated to machines but must leave humans accountable. Similarly, the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots is promoting the establishment of an international treaty prohibiting the use of fully autonomous weapons. While the actions of these organizations are commendable, their efforts have so far remained marginal.

These organizations—and others like them—would do well to take a page from the antinuclear weapons movement. While not perfect, the antinuclear weapons movement was largely successful in preventing the spread, testing, and use of nuclear weapons. (There were two main waves for the movement; the first one, from the mid-1950s through the early 1960s, led to the establishment of the Partial Test Ban Treaty and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The second wave, in the mid-1980s, led to the establishment of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.)

But what made the movement against nuclear weapons successful? And what lessons can be learned from the antinuclear weapons movement that could make the campaign against autonomous weapons systems more efficient?

Keys to success. The antinuclear weapons movement was one of the most successful movements in history, say historians such as Lawrence Wittner, author of “Confronting the Bomb”—a conclusion echoed by first-hand participants, such as Helen Caldicott. The antinuclear movement emerged in the 1950s, when it was composed mostly of social and peace activists, as well as many scientists who realized the devastating implications of the Bomb. The campaign was tightly focused and had three goals: a ban on nuclear tests; the institution of arms control and disarmament; and a ban on the use of nuclear weapons.

The antinuclear movement did several important things which were key to its success.

First, it raised public awareness, launching a massive media campaign to help educate the public (as well as decision makers) about the dangerous implications of nuclear weapons. Activists distributed leaflets, placed ads in newspapers and magazines, did radio and television interviews, wrote books, and produced movies, all in an effort to fight the era’s conventional wisdom. Some common assumptions at the time included the belief that nuclear testing was safe; that nuclear weapons were just “bigger bombs;” that a nuclear war can be won; and that people could survive a nuclear attack. The campaign managed to change public opinion, creating strong public opposition to nuclear weapons.

(It should be noted that while the campaign was successful in raising awareness in the West, it was less successful in other regions such as the Middle East and South Asia. This was mainly due to a lack of advocacy networks within these regions, and between these regions and the West—which limited cooperation and the sharing of knowledge and information.)

Second, the campaign brought about political pressure to end nuclear testing and stop the spread of the Bomb by mobilizing protesters—ranging from tens of thousands to even millions at its peak—that took to the streets in Western Europe, the United States, Canada, and Australia. Working from the bottom-up, this public opposition significantly constrained decision makers, making it almost impossible for those in power to support pro-nuclear policies. Furthermore, politicians were often forced by public pressure to support policies and treaties they opposed.

For example, public opposition in the late 1950s prevented the deployment of nuclear missiles in Western Europe (which the United States and European powers favored) and facilitated the establishment of the NPT. Public opposition to nuclear tests also led to the establishment of the Partial Test Ban Treaty (not because governments did not want to continue testing but because of growing public fears about the implications of nuclear tests). In the mid-1980s, public pressure enabled the establishment of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty—an agreement based on President Reagan’s “Zero Option,” which US officials thought the Soviets would never agree to. The European powers were very much opposed to the treaty but had no choice because their publics supported it.

The campaign also created a negative aura around nuclear weapons. Activists worked hard to change public perceptions about nuclear weapons, successfully assigning them negative labels such as “weapons of mass distruction” and “holocaust weapons,” reversing the image of nuclear weapons as merely a form of super bombs. Since the 1970s, activists also argued that nuclear weapons were useless, expensive, and out-of-date. These efforts damaged the image of nuclear weapons as symbols of power and prestige, making them less desirable to states.

From the A-bomb to AI The development of the nuclear bomb was a revolution, whose full implications were not clear to most of the general public. But citizens did generally understand almost immediately that this weapon was more powerful than any other weapon and in a league of its own. Consequently, it was not too difficult to convince the public and decision makers of the need for arms control and disarmament.

But the development of autonomous weapons systems powered by artificial intelligence is evolutionary, not revolutionary. The slow, step-by-step manner of the progress of AI technology is forcing the world to acclimate, nearly imperceptibly, to the upcoming change. Without much realizing it, people are becoming more and more dependent on these technologies, making the possibility of reversing the process unlikely. Therefore, one of the challenges for the campaign to ban AI-driven weapons will be to convince the public of the danger that these technologies possess.

It is easy to find oneself thinking: “Why are autonomous systems okay in our houses, our roads, our hospitals and airports, but not for military use?” So, one of the challenges for the campaign against autonomous weapons systems will be to draw a bright, clear line between the positive and negative uses of these new technologies. In this, the ICRC may be on the right track, framing the battlefield use of autonomous, artificially intelligent robots as a legal, moral, and ethical issue, allowing it to label certain uses of AI technology as immoral and unethical.

One other lesson from the antinuclear movement is the importance of cooperation. The movement involved dozens of organizations (including peace activists, scientists, and environmentalists, to name a few) in many countries, working together. If the campaign against autonomous weapons systems is to succeed, cooperation is similarly vital. The involvement of scientists in the antinuclear weapons movement was another advantage for the movement, because these scientists held strong credibility with decision makers—a credibility that social activists often lack. Getting prominent scientists on board the anti-AI movement could help strengthen the position of the campaign against autonomous weapons systems.

One big difference should be noted between today’s campaign against AI on the battlefield and the antinuclear campaigns of yesteryear: The antinuclear movement didn’t have the advantage of social media, which makes it easy today to reach millions of people all around the world and share information.

What we can learn from the past. The campaign against nuclear weapons led to the establishment of many important agreements and treaties. But its greatest successes were the establishment of a nonproliferation norm and the taboo on the use of nuclear weapons. The greatest challenge for the present-day campaign against autonomous AI technology on the battlefield would be to establish similar norms.

The campaigns against nuclear weapons and autonomous weapons systems both attempt to prevent the use and spread of new and dangerous weapons systems. Therefore, the successful movement against nuclear weapons can be used as a model for the campaign against autonomous weapons systems—as long as those running today’s campaign remember the strategies that proved key to the success of the antinuclear movement: powerful symbols, a clear message, tightly focused goals, cooperation across diverse constituencies, getting scientists on board, the use of all forms of media to get the message across, political pressure, public stigma against the use of this weapon, and the establishment of norms and taboos.

And maybe someday, someone will refer to the movement against battlefield AI as “the ordinary thing done extraordinarily well.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: AI, antinuclear movement, autonomous weapons

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons