Artistry, factuality, Hiroshima, and John Hersey

By John Mecklin | April 24, 2019

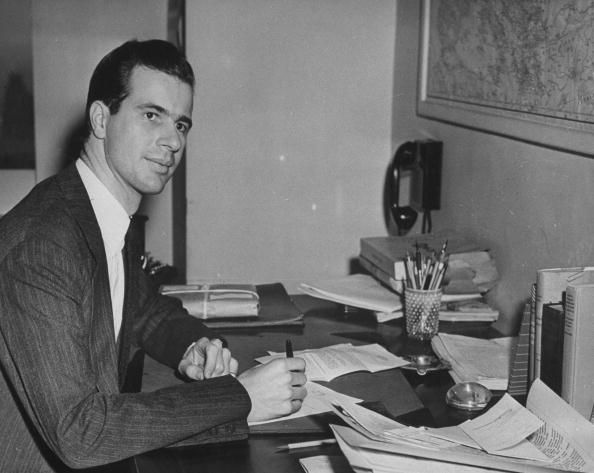

John Hersey at his desk, pen in hand, in the office at TIME. (Photo by Time Life Pictures/Pix Inc./The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

John Hersey at his desk, pen in hand, in the office at TIME. (Photo by Time Life Pictures/Pix Inc./The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Most Bulletin readers will recognize the name John Hersey—or, at least, his most famous book, Hiroshima. But I’m betting few will know most of the fascinating details they can learn about Hersey, his extraordinary early success, and his role as a journalistic innovator from Nick Lemann’s most recent piece in the New Yorker. “John Hersey and the Art of Fact” is in some sense a review of Jeremy Treglown’s new book on Hersey, “Mr. Straight Arrow,” but Lemann is certainly after (and achieves) more than one generally expects from a book review.

In his piece, Lemann—a New Yorker staff writer and Columbia Graduate School of Journalism professor and former dean—riffs off Treglown’s book as he describes Hersey’s remarkably quick rise into the upper levels of American and English intellectual life. Hersey, after all, won a Pulitzer Prize at age 30 for his novel, A Bell for Adano, and “he got a congratulatory letter from the Secretary of State, Edward Stettinius, Jr., and dined with Jean-Paul Sartre at the home of Alfred Knopf, who published both of them. His decades-long association with The New Yorker began when he and [John F.] Kennedy, out for the evening at a night club called Café Society, encountered William Shawn, then the magazine’s managing editor, and had a conversation about the PT-109 episode.”

But its social-climbing descriptions aside, the value in this piece lies in Lemann’s discussion of how Hiroshima—originally an article that filled an entire issue of the New Yorker with its clear-eyed description of the aftermath of the atomic bombing of that city—was both a turning point in the magazine’s transition from a purveyor of light entertainment into something more substantive and a genuine journalistic innovation, the real beginning of modern narrative nonfiction. “Then, too, Hiroshima was a marvel of journalistic engineering,” Lemann writes. “Someone had given Hersey a copy of Thornton Wilder’s 1927 novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, to read on the destroyer that took him to East Asia, and he adopted the novel’s technique of braiding the stories of an ensemble of characters. From the dozens of people he interviewed, he chose six, alternating among them so that each character appeared in every major phase of the chronology. Hersey’s writing voice is calmly recitative, bordering on affectless—’deliberately quiet,’ as he later put it.”

In essence, though the term was not used generally for a couple of decades, Hiroshima was America’s first nonfiction novel, a form that Hersey largely avoided as he shifted his emphasis to fiction writing. But Hersey’s enormous accomplishment in recounting the reality of that first atomic bombing was taken up and built upon by a following generation of writers—Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe, and Truman Capote among them—with whom Hersey argued about what was and was not proper in this new form of factual storytelling.

The writers in our audience will perhaps be most interested in this article’s technical and yet somehow concise passages, in which Lemann (himself a stylist of no small note) explains the core of what is today often called narrative nonfiction: “The relationship between fiction and nonfiction is like the one between art and architecture: fiction is pure, nonfiction is applied. Just as buildings shouldn’t leak or fall down, nonfiction ought to work within the limits of its claim to be about the world as it really is. But narrative journalism is far from artless. In crafting Hiroshima, Hersey left out most of his interview material so that he could focus on a limited number of characters whom his readers would remember; he built suspense by cutting away from each character, as he notes in [a] Paris Review interview, at ‘the verge of some kind of crisis’; and he carefully calibrated the pace at which the events he was describing unfolded.”

The much larger portion of our audience concerned primarily with altering the world’s tragic and exceedingly dangerous approach to the control of nuclear weapons will want to read this piece to the end, where they will find these three sentences and I think come to see—as I do—how the Bulletin’s mission in the world and John Hersey’s most memorable accomplishment in some ways overlap: “Hersey had received his own call during the Second World War, which he was early in coming to understand primarily as a great catastrophe rather than an inspiring American triumph. He went to the scene, he tirelessly looked where most journalists didn’t, and he found ways of writing about what he saw that gave his journalism an enduring power. In a long, relentlessly productive career, that’s what stands out.”

Publication Name: The New Yorker

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, What We’re Reading