A tiny crustacean and the deep-sea fallout of nuclear testing

By Thomas Gaulkin | May 10, 2019

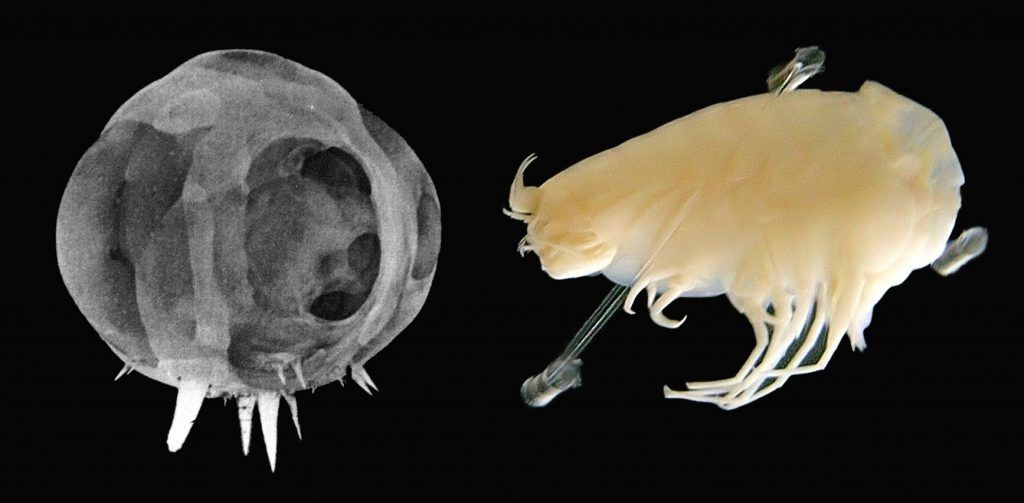

Left: Milliseconds into one of the 1952 "Tumbler-Snapper" atmospheric nuclear tests. Right: Millimeters-long Hirondellea gigas, a crustacean found in the Mariana Trench. Not to scale.

Left: Milliseconds into one of the 1952 "Tumbler-Snapper" atmospheric nuclear tests. Right: Millimeters-long Hirondellea gigas, a crustacean found in the Mariana Trench. Not to scale.

If you’ve been living under a rock, you might not know that human activity has been changing the world for the worse. The latest Earth-shattering news is that over 1 million species, or an eighth of all life on the planet, are in danger of vanishing, some within decades.

Now, if you’ve been living under a rock at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench, you are excused for having a different perspective. After all, if you’re there, you are 36,000 feet below sea level, there’s no light, and the pressure is like hoisting the Eiffel Tower on your shoulders. An inhospitable place, where few creatures, and certainly no humans, can survive.

But a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters proves that even at those depths, the natural world is not immune to the chaos far above. As detailed by Smithsonian magazine, the authors of the study discovered that the bodies of amphipods—a type of bottom-feeding crustacean in the deepest areas of the ocean—contain the atomic residue of hundreds of atmospheric nuclear tests conducted from 1945 through the early 1960s.

As the one-time surplus of the carbon-14 created by those nuclear tests dissipates, scientists can measure the quantity of “bomb carbon” remaining in cells to determine their age and the lifecycle of organisms. Most deep ocean water is free of this additional carbon-14. So because the trench-dwellers’ bodies were found to contain quantities of bomb carbon comparable to animals that lived near the ocean surface years ago, researchers now better understand how long those deep sea creatures live (much longer than their crustacean cousins up top) and their source of food. Freshly digested material showed much lower, and therefore more recent, levels of bomb carbon, which suggests some material can travel the miles to the ocean floor much more quickly than previously thought.

That’s great news for people studying amphipods. But one of the study’s co-authors got at the bigger concern in a press release accompanying the publication:

“There’s a very strong interaction between the surface and the bottom, in terms of biologic systems,” said Weidong Sun, a geochemist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Qingdao, China. “Human activities can affect the biosystems even down to 11,000 meters, so we need to be careful about our future behaviors.”

Publication Name: Smithsonian magazine

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, What We’re Reading