Cardiologists take Doomsday Clock to heart

By Thomas Gaulkin | June 19, 2019

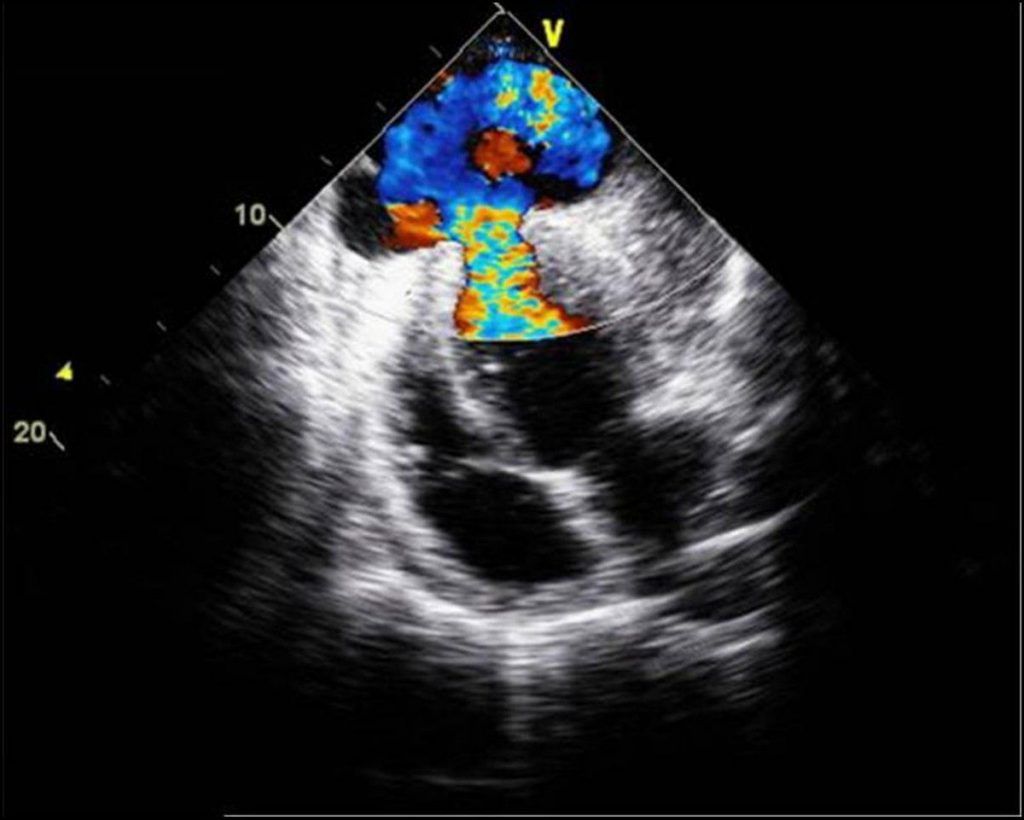

Transthoracic echocardiography of apical pseudoaneurysm. Four-chamber view demonstrates a large discontinuity of the ventricular wall in the apex, with the image resembling a "mushroom cloud". (Figure from Cardiovascular Ultrasound, 2009 7:36.)

Transthoracic echocardiography of apical pseudoaneurysm. Four-chamber view demonstrates a large discontinuity of the ventricular wall in the apex, with the image resembling a "mushroom cloud". (Figure from Cardiovascular Ultrasound, 2009 7:36.)

Your heart health will probably be the least of your concerns when you hear that ICBMs are inbound. You’ll certainly have other things to worry about. But to some cardiologists, the medical profession has more to say about stopping nuclear war than you might think.

In a commentary titled “Cardiac Events and Nuclear War: Prevention by Cardiovascular Specialists” that begins, literally, with “The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists,” three US doctors who have been vocal against nuclear weapons since the Cold War explain that cardiologists have “made major contributions to reducing prior nuclear threats.” In the piece, recently published in the American Heart Association’s journal Circulation, doctors James Muller, John Pastore, and Amir Lerman describe how “the cardiovascular events we work to prevent—sudden cardiac death, myocardial infarction, rupture of an aneurysm, stent thrombosis, and stroke—are low-probability, high-consequence negative events,”much like nuclear war.

“Although cardiac risk may be low in any given year,” they write, “cardiologists act on the basis of cumulative risk over a decade or a lifetime. For the nuclear threat, which has a low annual risk, we must think in terms of the lifetime of humanity.”

The comparison continues, redefining nuclear deterrence strategy as a kind of bad habit: “Prevention of cardiac events in most cases requires a change in behavior: cessation of smoking, taking medications for hypertension, weight loss,” they write. “Paradoxically, at moments of greatest danger, when the threat is most visible, the possibility of change is greatest—a linkage familiar to cardiologists when a lifelong smoker quits after having a heart attack.”

Taken on its own, relating individual heart risks to the risks facing the entire species might seem like a stretch. And it’s not a subtle analogy—the authors include a chart of movements on the Doomsday Clock since it was first set in 1947 that, perhaps by chance, looks a bit like an electrocardiogram.

But health professionals have a more pragmatic role to play, the authors argue. “With an energetic worldwide educational effort … on the nuclear threat, we can join our colleagues in moving the hands of the Doomsday Clock back from the midnight hour.” Both Muller and Pastore were key leaders of International Physicians for Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW), an organization founded in 1980 to create a scientific bridge between the United States and the Soviet Union; it has since contributed important research on the physiological effects of nuclear weapons development and use. Many of the group’s most prominent affiliates from both countries have been cardiologists. The 1985 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to IPPNW in recognition of physicians’ role in “helping the public visualize threats and to communicate complex scientific issues in understandable terms.”

Of course, this isn’t the first or only way people outside the international security and policy world have worked to bring their expertise to bear on the threat of nuclear war. There have been many efforts to pursue peace through creative diplomacy (including cultural and sports exchanges, often led by ordinary citizens). In fact, Eugene Rabinowitch, the founding editor of the Bulletin whose keen outlook on international security tracked much of the Cold War, kept his day job as one of the world’s foremost experts on—you guessed it—photosynthesis.

The cardiologists behind this latest heartfelt call to action also seek to use their knowledge to “educate the public to a full understanding of the scientific, technological and social problems arising from the release of nuclear energy,” as Rabinowitch and his Manhattan Project colleagues declared when they first created the Bulletin more than 70 years ago.

“Health professionals can make the unimaginable imaginable (and hence preventable),” the heart doctors write in Circulation, “alerting the public to the chance of an accidental nuclear war and educating about the cumulative probability aspect of the threat.”

Publication Name: Circulation

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.