Cover the climate crisis like it is one

By Dawn Stover | July 8, 2019

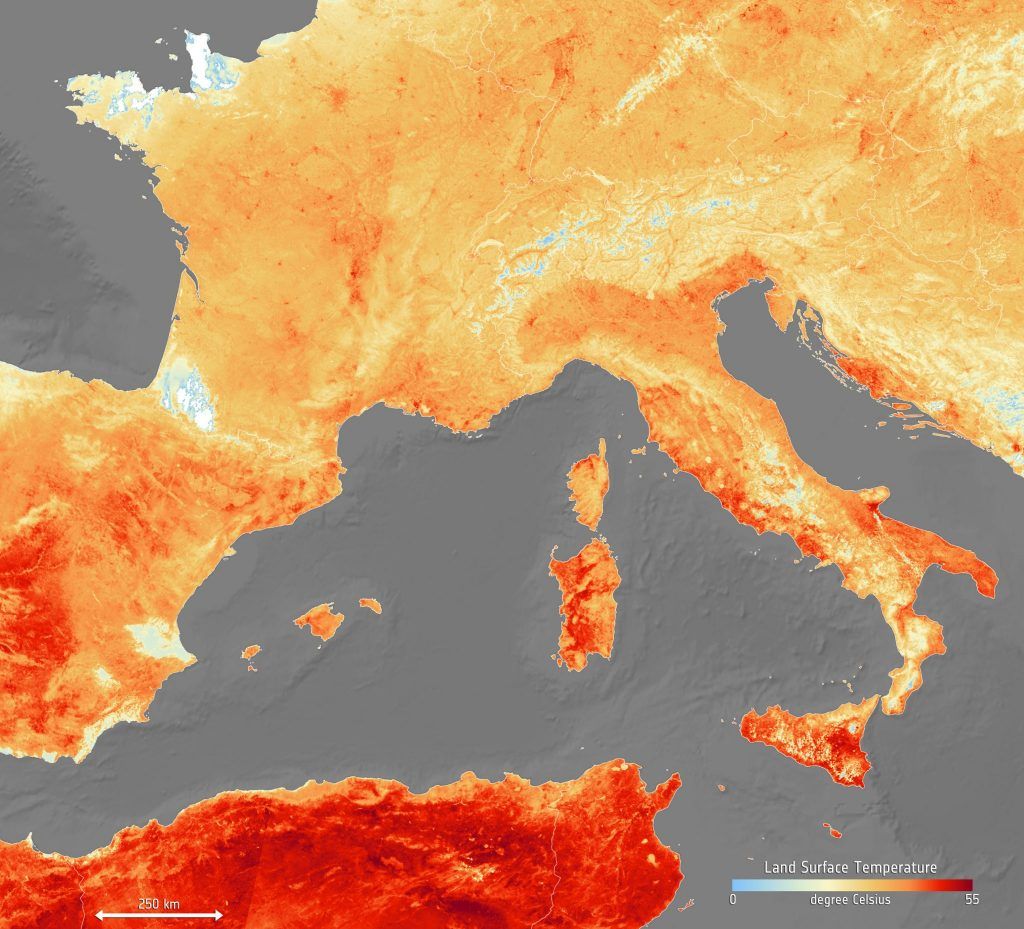

Last month’s heat wave broke records across Europe. This map shows land-surface temperatures on June 26. White areas in the image are where clouds obscured readings, and light blue patches represent either low temperatures at the top of a cloud or snow-covered areas. Credit: European Space Agency

Last month’s heat wave broke records across Europe. This map shows land-surface temperatures on June 26. White areas in the image are where clouds obscured readings, and light blue patches represent either low temperatures at the top of a cloud or snow-covered areas. Credit: European Space Agency

Journalists, scientists, and policy experts routinely invoked the phrase “climate change” back in the good old days—2016, that is—when it seemed like the Paris Agreement might actually set the world on a path to a stable climate. Three years and a world of hurt later, some are calling for a new language to describe the threat to humanity’s future: “climate emergency,” “climate crisis,” “climate breakdown,” and “climate chaos.”

There’s no question that the Paris Agreement is obsolete. The temperature recently reached 113 degrees Fahrenheit in France, a country where many buildings don’t have air conditioning. In the United States, more than 70 medical groups urged political candidates “to recognize climate change as a health emergency.”

Yes, this is an emergency. And yes, the term “climate change” is not only worn-out and boring, but also politically fraught. However, the media have a much bigger problem than what vocabulary to use. Many of the world’s largest news organizations simply aren’t telling the climate story with anything approaching the urgency and attention they devote to a glut of trivial subjects. Updating a style guide does little to fix that problem. Here’s what a meaningful solution looks like: a well-funded commitment to publish more and better stories on one of the most important, life-threatening issues of our time.

The new lingo. Sometimes a change in language can change the conversation. I applaud The Guardian newspaper for instructing its reporters to use terms that “more accurately describe the environmental crises facing the world.” For example, The Guardian deemed “global heating” better than “global warming,” although both are acceptable. The Guardian is doing a far better job of covering climate than most newspapers, and it is one of the Bulletin’s partners in the Climate Desk collaboration dedicated to expanding coverage of this issue.

The Spanish-language network Telemundo has also updated its language. Last month, Telemundo announced that its news department will start using the term “climate emergency” instead of “climate change” or “global warming,” as part of a process “to incorporate more accurate scientific terminology into its environmental reporting.”

Environmental groups have been pressuring other news organizations to follow suit. The Sierra Club, Greenpeace, 350.org, and others sent a June 6 letter urging the heads of Fox, CBS, ABC, NBC, MSNBC, and CNN to “call the dangerous overheating of our planet and the lack of action to stop it what it is—a crisis—and to cover it like one.”

So far, though, very few segments on network news have characterized climate change as a “crisis” or “emergency.” Last year, according to a report by the nonprofit organization Public Citizen, only 3.5 percent of the national TV news segments that mentioned climate change used either of these terms. Fox News, which dominates the ratings, mentioned the words only five times—and only to mock the idea that climate change is a crisis. “When media outlets consistently fail to use language that conveys that climate change is a crisis or emergency, they unwittingly put a heavy thumb on the scale in favor of complacency and inaction,” said David Arkush, managing director of Public Citizen’s Climate Program.

Calling climate change a crisis is certainly a major improvement over referring to events such as the scorching European heat wave as “the new normal” (when there is nothing normal about it), but the new vocabulary is just a baby step. It’s that second, giant step—covering the climate crisis like it is one—that really matters.

Unconnected dots. Unfortunately, America’s biggest news organizations are repeatedly neglecting their responsibility to cover the crisis. Even when there is an event that is obviously related to global warming, such as an extreme heat wave, media reports often fail to connect the dots.

For an analysis published in January, Public Citizen searched transcripts from six national TV news networks, articles from the top 50 US newspapers, and 32 leading online news sources for terms such as “record heat wave” and “historic flooding.” In 2018, only about one-third of the newspaper reports containing these terms also mentioned climate change. For television news, it was just 22 percent. Online news mentioned climate more often, but still only 38 percent of the time.

“Many of us have recognized that our coverage of global warming has fallen short,” said journalist Bill Moyers in remarks—aptly titled “What If We Covered the Climate Emergency Like We Did World War II?”—at a recent conference on climate coverage. Moyers said: “There’s been some excellent reporting by independent journalists and by enterprising reporters and photographers from legacy newspapers and other news outlets. But the Goliaths of the US news media, those with the biggest amplifiers—the corporate broadcast networks—have been shamelessly AWOL, despite their extraordinary profits.” (Although many local newspapers are suffering, TV networks are faring much better in the new media landscape—and can easily afford to devote more programming to climate coverage, and to invest more resources in researching and producing climate stories.)

Moyers reminded the audience how Edward R. Murrow and other journalists insisted on writing about Hitler’s advances in Europe in 1939, defying orders to put together a more upbeat story about dance music at European nightspots. If only the reporters at ABC World News Tonight would mount that kind of resistance to their bosses, who devoted more air time to England’s royal baby Archie in one week than they did to climate change during all of 2018.

Of course, increased coverage doesn’t necessarily mean better coverage. But a genuine crisis merits an increase in both quantity and quality.

An abstract issue. One of the biggest challenges for journalists covering climate is that it’s an abstract issue to most people. You can hug a tree, but you can’t hug the climate.

Unfortunately, coverage of climate has often come at the expense of covering more traditional environmental issues—such as deforestation, species extinction, and pollution—that tend to be less abstract. But the climate crisis isn’t just changing weather patterns and threatening human-made infrastructure; it is putting the entire natural world at risk. That’s our life support system, and it is a physical reality rather than an abstraction.

In the first week after the United Nations Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services released an alarming estimate that 1 million animal and plant species are in jeopardy, 31 of the nation’s top 50 newspapers “didn’t see fit to print that humans are causing one of the fastest mass extinctions in planetary history, and one that will take 10 million years to recover from,” said Public Citizen’s Arkush.

It won’t matter if we prevent sea level rise from taking out our homes but lose the natural habitats and organisms that our cities utterly depend on. A climate “emergency” is already making some people willing to throw in the towel on protecting natural habitats such as forests (which must now be “thinned” to prevent “catastrophic” wildfires) and deserts (eyed as sacrifice zones for “clean energy” generation and storage).

One if by land. While “climate crisis” packs more of an emotional punch than “climate change” or “global warming,” reaching people on an emotional level is going to take far more than changing a few words. It’s going to take a recognition that nature is even more indispensable than science and technology. And it’s going to take a radical shift that puts the media on a war footing.

“Instead of sleepwalking us toward disaster, the US news media need to remember their Paul Revere responsibilities—to awaken, inform, and rouse the people to action,” according to the Columbia Journalism Review. That publication has partnered with The Nation in a project to improve US media coverage of the climate emergency, an effort “grounded in the conviction that the news sector must be transformed just as radically” as other sectors of the global economy.

It can’t happen too soon.

Editor’s note: This article contains a correction made after publication. The temperature during Europe’s recent heat wave reached 113 degrees Fahrenheit in southern France, not in Paris.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: climate crisis, journalism, media

Topics: Climate Change, Columnists