A cross taken from a Nagasaki cathedral after the atomic bombing gets returned 74 years later

By Matt Field | August 7, 2019

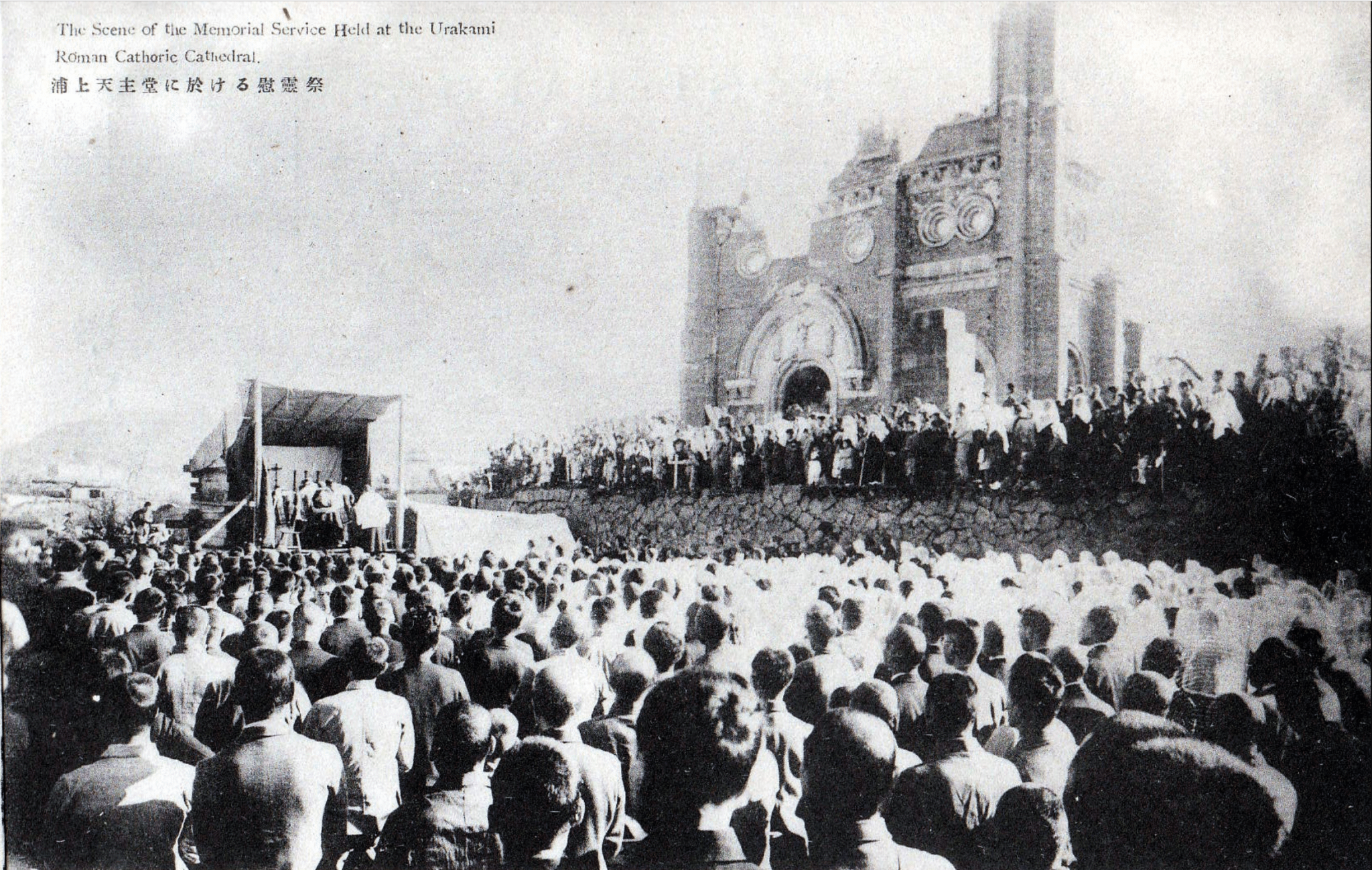

A cross from the rubble of Nagasaki's Urakami Cathedral. Credit: Randy Sarvis / Wilmington College.

A cross from the rubble of Nagasaki's Urakami Cathedral. Credit: Randy Sarvis / Wilmington College.

Short on time and fuel, the crew members of the B-29 bomber Bockscar flew over Nagasaki, Japan, scanning for an opening in the clouds. They had already abandoned their initial target, the city of Kokura, due to low visibility. Over Nagasaki, in the vicinity of a massive Mitsubishi arms plant, the crew found the clear patch of sky they needed to complete the mission: to drop the world’s most powerful weapon, a 4.5-ton plutonium bomb dubbed Fat Man. The detonation killed tens of thousands and decimated the city, all in an instant. Amid the ruins, just 500 meters from ground zero, were the collapsed roof, damaged pillars, and charred sculptures of the Urakami Cathedral, the locus of a vibrant Catholic community spawned during Nagasaki’s history as a trading port.

To the Nagasaki Christians, the bombing was yet another trial for a group long accustomed to persecution and adversity. They’d been tortured, banished, and executed. The shoguns who ruled feudal Japan maintained a ban on Christianity for hundreds of years, forcing adherents to practice their faith in secrecy until the ban was lifted in 1873. Then on Aug. 9, 1945, just 20 years after the Urakami Cathedral was completed, the atomic bomb destroyed it. Along with a priest and several parishioners who were inside at the time, much of the church’s history was lost. But 74 years later, the since-rebuilt cathedral got back a small piece of that history: a cross, mostly forgotten, that had been taken from the rubble. Tanya Maus, the director of Wilmington College’s Peace Resource Center, gave the cross that had hung in the rural southwest Ohio college for decades to the archbishop of Nagasaki on Tuesday.

Maus said a former US Marine, Walter Hooke, gave the artifact to the Quaker college in the early 1980s. Hooke, who died in 2010, had been stationed in Nagasaki after the bombing and had developed a relationship with the bishop of the city, who may have given the cross to Hooke. After seeing visitors from Nagasaki react to the cross—some moved, others perplexed as to how Hooke got a hold of it—Maus reached out to church officials in Nagasaki in April. “I started to think about the idea of ‘should it really be here? Maybe it needs to be in Nagasaki, where people can sort of explore that history more and the meaning of the cross more.’”

At the Peace Resource Center, the cross had been a starting point to engage local Christians in conversations about the atomic bombs and nuclear issues. “For me, it shouldn’t matter. It doesn’t matter whether you’re Catholic, or whether you’re religious; it’s an issue of humanity–the use of nuclear weapons,” Maus said. “But for some people, that was an entry point to understand the atomic bombings and have a sense of their destructiveness.”

According to the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, the church in Urakami had 14,000 devotees, several of whom died inside along with a priest. They were crushed by falling debris. Back at Wilmington College, the cross from the ruined cathedral had helped visitors understand the story of the bomb. “The fact that the United States, a country that in some sense based itself in Christian ethics, was dropping an atomic bomb on a Christian community–I think for me, I hoped that would make a strong impact on people,” Maus said.

“For me the cross represents human depravity. The utter stripping away of values, in this case Christian values, but it could be any values, that keep human beings from killing each other and destroying each other,” Maus said. “Part of giving it back was letting go of that and making it accessible to people who want to find their own meaning in it.”

Exactly how Hooke came to possess the cross is uncertain. His son told The Asahi Shimbun that Hooke had befriended Nagasaki’s bishop, who gave the cross to Hooke, perhaps in the hopes that it might change American’s perceptions of the bomb. What is clear, Maus said, is that the guitar-case-sized cross came from the cathedral. The archbishop, journalists, and others who looked into the issue found a photo in which the cross appears to be lying in the ruins. The story has generated intense media coverage in Japan, where, Maus said, “people are surprised. Why after all these years, is this place giving the cross back? There are lots of mysteries. How did it get there? Who is this Walter guy?

Maus said the cross will be displayed alongside another artifact from the cathedral, the head of a wooden Virgin Mary sculpture known as the Bombed Mary, whose glass eyes were melted by the atomic blast. According to The Japan Times, the cross will be on display in time for a mass Friday that will reflect on the 74th anniversary of the bombing.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

Quite a story. Thank you. Borrowed a book. Nagasaki: life after nuclear war. It’s written from the perspective of civilians that were there, under the bomb.