Interview: Nuclear research and the quest for scientific equity in Ghana

By Abena Dove Osseo-Asare, John Krzyzaniak | October 15, 2019

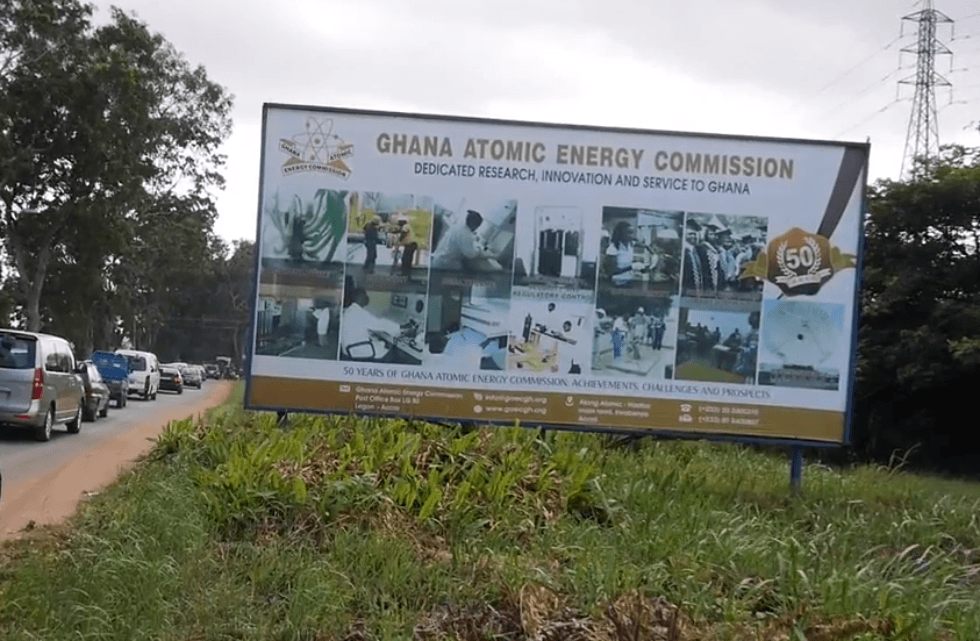

Commemorative cloth for the 50th anniversary of the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission (photo by Abena Dove Osseo-Asare/Eyram Amaglo)

Commemorative cloth for the 50th anniversary of the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission (photo by Abena Dove Osseo-Asare/Eyram Amaglo)

At the time of decolonization, Westerner researchers looked down on their African counterparts as inferior, yet atomic scientists in Ghana persisted, finding ways to continue their training and advance scientific knowledge. In this interview, Abena Dove Osseo-Asare, a historian of medicine and science and associate professor at the University of Texas in Austin, tells the story of their decades-long pursuit of what she calls scientific equity, which was driven by a simple impulse to be taken seriously as an equal stakeholder in global science. She explains how Ghana tried and failed to buy a nuclear research reactor from the Soviet Union in the 1960s, how Ghanaian scientists continued on their work throughout the Cold War and eventually got a research reactor from China in 1994, and how everyday Ghanaians think about the work of the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission today.

John Krzyzaniak: Let’s start at the beginning of Ghana’s nuclear story. Ghana gained independence from Great Britain in 1957 and began its quest for a nuclear research reactor almost right away, in the early 1960s. And it was actually very close to getting a research reactor from the Soviet Union. Why did Ghana’s political leadership want to invest in nuclear research at the time?

Abena Dove Osseo-Asare: If you talk to scientists in Ghana, the common story is that the idea of bringing in a reactor started with Kwame Nkrumah around 1957, when the country first gained independence from the UK. But digging through the archival record, both in England and in Ghana, it seems that there was actually an initiative to bring in a reactor when Ghana was still a British colony, as early as the mid-1950s.

There were two teams of British physicists—one at the university that became University of Ghana and one at the university that became Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology—and they were actually both vying for a small research reactor.

It was not too out of the ordinary at that point for an African colony to house a nuclear reactor. In fact, the university that became University of Kinshasa in what is now a Democratic Republic of Congo did receive a nuclear reactor around the same time. That reactor was partially given as a gift through the United States Atoms for Peace initiative, since Belgian Congo had provided much of the uranium used by the Manhattan Project including for the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Egypt—at the time the United Arab Republic—had its first Soviet made reactor open in February 1961. South Africa built a 20-Megawatt reactor that went critical in 1965. So Ghana was following these developments.

So the colonial government in the Gold Coast was all in favor of bringing in a reactor, but with independence on the horizon, British officials back in London were not so sure about it.

To your question of why did they want to reactor, I think in part it was this atmosphere where a lot of researchers around the world were interested in being able to create their own radioisotopes to do medical research, to use them as tracers in organisms to run experiments.

Once it gained independence, Ghana went through the Soviet Union to try and import a reactor. And this way, instead of researchers having to go to somewhere like England to do an experiment, they would be able to do them at home.

JK: So Ghana did make an agreement with the Soviet Union, but it never got the reactor. What happened?

AOA: When it was the British Gold Coast colony, officials in London didn’t support importing a reactor on the eve of independence. However, when Kwame Nkrumah became the first independent leader of Ghana, he initiated a dialogue with the Soviet Union to set up both a power station as well as a research reactor. And he had an engineer named Robert Patrick Baffour, who was then head of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, go to the Soviet Union to make the agreement.

Baffour, either on his own initiative or following conversations with Nkrumah, decided to downgrade the initial plan of bringing in both a research reactor and one large enough to generate electricity. Instead, they decided to go for only the former. They wanted to import a small 2-Megawatt pool-type reactor (an IRT-2000) based off of one built at the Kurchatov Institute in Moscow.

The project was 90 percent complete when Kwame Nkrumah was removed from office, in a coup d’état in 1966. They had built cooling towers, as well as a large building, which remains empty to this day on a hill in Kwabenya, where they were going to put in the reactor. And a lot of the parts that were shipped in were saved in boxes for about a decade. Some of the scientists at Ghana Atomic Energy Commission have even gone so far as to say that the fuel rods were on a ship heading to Ghana and then got diverted.

And we actually know a lot about that proposed reactor, in part because after the coup d’état British officials came in and did an overview and research into what Ghana had been up to.

There was a lot of interest, because you can imagine in this period, the British, the French, the Americans, and the Soviets are all trying to be at the forefront of nuclear technologies, and they’re not really talking to each other. And so for a newly independent country like Ghana to get ahold of a reactor made by the Soviets, this allowed the British to scrutinize some of the technology.

JK: Did the Ghanaian scientists ever try to recycle any of the components later on?

AOA: When the project was re-initiated in the 1970s, the Ghanaians scientists hoped that it wouldn’t be such a big deal to put it all back together and get in the fuel rods and get it to work. This is when they opened up the boxes of parts that had been saved to see if anything might be salvaged. But at this point the Soviets were going to charge a lot of money to Ghana to help them complete the reactor.

The scientists also conferred with countries including England and the United States, but nobody really wanted to make a hybrid reactor combining the Soviet components with British and American or some other West German part.

So they were sort of held hostage to this partial project.

JK: Obviously, that’s not the end of the story. Eventually, Ghana did get a research reactor from China, which went critical in 1994. So what kinds of things were Ghanaian scientists doing in the 1970s and ‘80s to keep the hope alive, or to keep advancing nuclear science even without a reactor?

AOA: Part of my new book looks at the experiences of the first group of Ghanaian scientists who trained in the Soviet Union and learned physics in Russian. One of them, G. W. Garbrah headed up the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission when he returned. And he characterized the 1960s and ‘70s as a training period for scientists, where they actually were able to use a relationship with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to advance the careers of Ghanaian scientists who wanted to take courses and earn degrees.

In addition, they became quite active, especially by the 1970s and ‘80s, in radiation protection work. There have been x-ray machines in Ghana since the 1920s or 1930s. By the 1980s, there were a lot of unregulated x-ray machines around the country, and one of the roles of the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission was to monitor radiation exposure and to put in place IAEA standards on radiation.

So that is one benefit of nuclear science in Ghana, making medical facilities safer. And there are now x-ray machines in ports in Ghana for cargo screening. There are also a number of sites around the country that do cancer therapies.

JK: So you’ve already mentioned a few of the benefits that this research has produced. Do the people of Ghana know about and appreciate these advances?

AOA: The Ghana Atomic Energy Commission is situated near a part of Accra, the capital city, called Atomic Junction, and the road that leads away from it is called the Haatso-Atomic Road. Along this road toward the reactor complex, you’ll see mini-buses looking for passengers and the bus operators will be shouting “atomic, atomic, atomic,” and it has really become this geographic designator separated out from the history of the entire Nkrumah vision for a nuclear reactor.

I interviewed people living in this area and asked them what they think was actually happening inside the campus. These discussions revealed some of the fault lines between the scientists, who have grandiose visions and have set goals for themselves that are quite high, and the people living around the Haatso-Atomic Road. You might go a mile or two away and find people without running water or washing their clothes by hand. And some feel disenfranchised because their land was taken to create the site for this reactor.

Because the scientists live in the neighborhood near non-scientists, there is some level of understanding, however. In interviews, locals knew that the scientists were doing research on yams, for example. So, there is actually some knowledge transfer that has happened just because the scientists aren’t completely isolated—they shop at the markets with their neighbors and they go to church with other people.

JK: Ghana is now working with China and Russia to build two nuclear power stations. Do average Ghanaian people support nuclear energy?

AOA: Employees at Ghana Atomic Energy Commission and those who have trained at the Graduate School of Nuclear and Allied Sciences to obtain the requisite knowledge are really excited to use their skill set. There are many who have really benefited from the opportunities, including scholarships, that Ghana Atomic Energy Commission and the graduate school has afforded them.

It’s important to remember that some of these people have been working to keep this dream alive for many years and working to create the scientific establishment and leadership they would need to manage these power stations. So, I think in terms of the scientists’ perspective, there is a lot of excitement.

In terms of how it may play out in the public arena, there are concerns about radioactive waste. There is an above ground radioactive waste site at the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission. The commission has been working with the United States to upgrade the facility there, including some experiments with using bore holes to dispose of the radioactive waste.

But for a nuclear power station, they’re going to have much larger quantities of waste than what they currently have for just the research reactor. One proposal is to transport waste to the coast and ship it elsewhere, either to China or another site. But even just figuring out how to transport the waste will be a challenge, particularly because of some of the rough roads in Ghana, let alone finding a site where it could be buried.

JK: You mentioned that some people still feel disenfranchised that the state took their land to build the research reactor. Is there a similar worry now about the projects for the nuclear power plants?

AOA: Well in the 1960s the Atomic Junction site was a secluded spot an hour outside of the capital city. Now, however, it is quite built up, and they certainly won’t put either of the power stations at the same site. They are in the process of finding sites that are more remote and that would have a larger body of water nearby. But questions remain in terms of how land management will happen, and how families that lose their land will be compensated.

Interestingly, with the search for new sites, some of the townspeople near Atomic Junction have said “Well, why don’t they relocate the research reactor?”

JK: What lessons does Ghana’s experience hold for other countries?

AOA: In my book, I talk about scientific equity, which I see as a desire to allow Africans to be stakeholders in scientific work and global science. This is an impulse that I trace to the 1960s but has continued up today. Kwame Nkrumah said that there’s no monopoly on ability—that Africans are as intelligent as people anywhere else in the world and they have a right to pursue scientific research.

So one lesson is for scientists from other countries who have trained to a very high level in nuclear technology and are interested in excited about the possibilities of running reactors themselves. One unfortunate component of the postcolonial moment was the British discounting the intellectual capacity of African scientists. Some of the archival statements are quite insulting, hearing the British saying things like “Ghanaians are trying to run before they can walk,” or “There are no scientists in Ghana.” These glib statements actually spurred on many scientists who were intent on proving that they could manage nuclear technology.

Editor’s note: For more on this subject, interested readers can find Osseo-Asare’s new book Atomic Junction here, and can watch a trailer for her forthcoming short documentary film here.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Ghana, nuclear energy, research reactor

Topics: Interviews, Nuclear Risk