Myanmar should finally come clean about its chemical weapons past—with US help

By Gregory D. Koblentz, Madeline Roty | March 11, 2020

In 2014, then US President Barack Obama and democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi met in Myanmar. Even as the United States was encouraging Myanmar's democratic reforms, there were thorny issues the US government couldn't ignore, including Myanmar's secret chemical weapons program. Credit: US State Department.

In 2014, then US President Barack Obama and democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi met in Myanmar. Even as the United States was encouraging Myanmar's democratic reforms, there were thorny issues the US government couldn't ignore, including Myanmar's secret chemical weapons program. Credit: US State Department.

In November 2012, US President Barack Obama arrived at Aung San Suu Kyi’s mansion, the place where the iconic democracy activist had spent much of the last two decades under house arrest, a political prisoner of the Myanmar military junta that controlled the isolated Southeast Asian nation. By the time of Obama’s visit, Suu Kyi was free, and, in fact, already a member of parliament. Her jubilant supporters thronged the gates of her house as Obama, the first US president to visit Myanmar, left his motorcade. Many in the crowd were doubtlessly soaking up a moment that they never could have imagined. In Suu Kyi’s garden, Obama announced that “flickers of reform” had given him the confidence to open “a new chapter between the United States and Burma.”

But even during those early feel-good days of the thaw, there were background issues the United States couldn’t just paper over with the pleasing narrative of a democratizing Myanmar. Most prominently, there was the persecution of the Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic group in the predominantly Buddhist country. And then there was a significant, but less noticed problem, one that went unmentioned in Obama’s 2012 speech in Suu Kyi’s garden: Myanmar’s secret chemical weapons program. Indeed, no US government official had publicly discussed the program since the Reagan Administration.

After years of denial, there are signs that Myanmar is finally making moves to come clean to the international community about its chemical weapons program, which is believed to be inactive. Last fall, after a US State Department official once again brought up the issue—this time in front of a roomful of diplomats at a meeting in The Hague—a high-ranking Myanmar official said his country is willing to address concerns about adherence to the Chemical Weapons Convention, the global treaty that bans chemical weapons activities. And, last month, Myanmar hosted a US delegation of experts to discuss the treaty.

Given the treaty’s goal of a world free of chemical weapons, even dormant programs need to be declared and destroyed as any remaining production equipment and agent stocks present a proliferation risk and raise questions about Myanmar’s commitment to the convention.

Myanmar’s chemical weapons past. Although the US government has known about Myanmar’s chemical weapons since the 1980s, it remains unclear why the country developed the program in the first place. Perhaps Myanmar, which has faced domestic insurgencies for several decades, was inspired by reports that the Soviet Union’s allies in Southeast Asia had used chemical or toxin weapons against their own insurgencies. Alternatively, Myanmar may have feared that these same countries would turn these weapons against Myanmar itself.

A September 1983 US government Special National Intelligence Estimate indicated that Myanmar had been seeking to produce the chemical warfare agent sulfur mustard since 1981, estimating that the country would be self-sufficient in production capability by 1984. Most likely, the report reasoned, the chemical weapons were “for use against internal insurgencies.” Myanmar was also included in other US intelligence reports in the mid-1980s as one of approximately a dozen countries suspected of developing chemical weapons. And in 1987, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, a European think tank, reported that Myanmar was producing mustard agent using equipment and chemicals procured from West Germany and Italy.

It wasn’t until March 1988 that the United States publicly accused Myanmar of developing chemical weapons during a briefing to Congress by Admiral William Studeman, the director of the Office of Naval Intelligence.

To date, the most detailed public information on Myanmar’s chemical weapons program is a declassified 1991 National Intelligence Estimate. The report concludes that, with West German assistance in the early 1980s, Myanmar built a small chemical weapons production facility that was used to manufacture about 500 liters of mustard agent. By the time of the report’s publication, Myanmar was not believed to be producing the agent any longer. The estimate also noted unverified claims from insurgents that the army had imported chemical weapons from China to use against them.

The US intelligence community and outside researchers were most likely pointing in their reports to the West German firm Fritz Werner, which makes arms manufacturing factories and equipment. The company has had an extensive relationship with the Myanmar government that began in 1956 with the construction of small arms and ammunition factories, a partnership that later expanded into civil and industrial projects, including fertilizers and heavy machinery. According to the Australian international security scholar Andrew Selth, senior company officials even became personal friends with General Ne Win, who ruled Myanmar after launching a coup in 1962.

And Myanmar isn’t the only country whose chemical weapons program the company allegedly aided. Fritz Werner has also been implicated in equipping Iraq during the 1980s, when Saddam Hussein’s forces regularly used the weapons against Iran. Fritz Werner, however, has denied helping Myanmar build a chemical weapons plant. A managing director of the company told Selth in 2000 that the company “is convinced that also the Burmese side never tried to build such a factory.”

Did Myanmar ever use chemical weapons? Ethnic factions in Myanmar have been fighting the national government more or less since the country gained independence from Britain in 1948. Just last August, insurgents attacked a military college and killed 15 people, a reflection of the ongoing tensions in the country. At the time, a rebel spokesman told Reuters that while Suu Kyi, who is now state counsellor and the de facto leader of the country, was promoting a peace process in the country, “nothing can happen if the military doesn’t participate.” Since the 1980s, when suspicions about Myanmar’s alleged chemical weapons program became public, insurgent groups have repeatedly claimed that the country’s military has used the banned weapons against them.

Some accusations involve blister agents like mustard and unidentified toxic agents, while others refer to chemicals such as white phosphorous and defoliants, substances which are not considered chemical weapons under the Chemical Weapons Convention. The attacks have reportedly been carried out with mortars, rockets, heavy artillery, and bombs resulting in symptoms such as nausea, difficulty breathing, rashes, and partial paralysis.

While the Myanmar military was accused as recently as 2016 of using an unspecified type of chemical weapon, Selth has observed “that no reports of [chemical weapons] attacks by the Burmese armed forces have ever been verified by independent sources.” Even critics of the military regime concede that “there is no evidence that locally-produced chemical weapons have even been used in the country.”

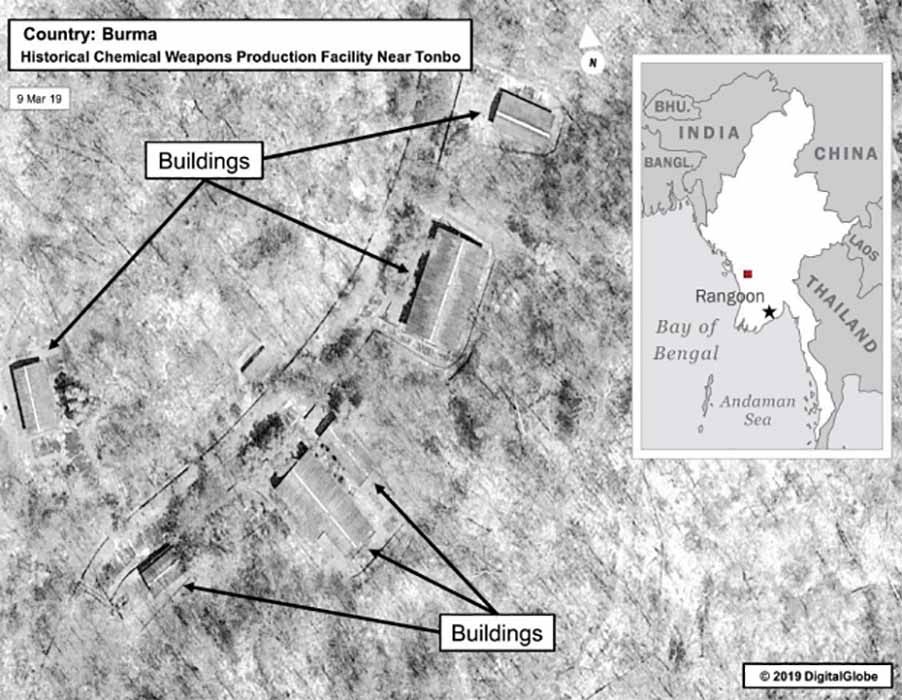

Where were Myanmar’s weapons made? Last fall, the State Department released a little-noticed unclassified report with additional details about Myanmar’s non-compliance with the chemical weapons treaty and alleged former chemical weapons program. According to the United States, in the 1980s, Myanmar built a chemical weapons production facility that produced a small stockpile of sulfur mustard. The State Department has high confidence that Myanmar’s primary chemical weapons research, production, weaponization, and storage center during the 1980s was located at a facility near the town of Tonbo. The department reported that the buildings at this facility are physically intact and may even still house production equipment and chemical warfare agents.

The report contains only a single image of the Tonbo site. Along with master’s student Darek Olsen, we geolocated the facility approximately 12 kilometers west of Tonbo, a small town on the west bank of the Irrawaddy River in the Bago Region of south-central Myanmar. The integrity of the buildings and the maintenance of the roads leading to the facility indicate that the site is still in use for purposes unknown and has not been entirely abandoned.

We geolocated the facility near the town of Tonbo at the following coordinates: 18°30’35″N 94°58’28″E.

In addition to the Tonbo site, the United States has also identified two other locations that were possibly involved in Myanmar’s undeclared military-run chemical weapons program, but the government has not released any further information about these facilities.

Much remains murky about Myanmar’s program. Why, for instance, did the country bring it to a halt, assuming US intelligence and outside reports are correct? At the international level, progress on chemical weapons negotiations in Geneva and the US government’s public identification of Myanmar’s activities in 1988 may have raised the diplomatic costs of the program. That same year, Myanmar experienced a deadly crack-down on pro-democracy activists and a military coup which led to the imposition of sanctions by several countries, including Germany. The increased international scrutiny and reduced access to necessary supplies for the program may have led to its cessation. Upon taking power, the new military-run government also began an extensive modernization effort for the Myanmar military which may have reduced the perceived value of chemical weapons.

In 1993, Myanmar was one of 130 countries that signed onto the Chemical Weapons Convention during a three-day show of support from countries around the world for the new treaty. For the next two decades, however, Myanmar did nothing to implement it.

Myanmar began undertaking democratic reforms beginning in 2010, and as the Obama administration sought to rebuild ties with the country, it didn’t entirely forget about the illicit chemical weapons program first identified in the 1980s. In fact, administration officials repeatedly pressed their counterparts in Myanmar.

In January 2015, the year Myanmar fully ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention, a US delegation travelled to Yangon to offer technical assistance with implementing it. There, the delegation once again pushed government officials about the program, but were met with denials that it had ever existed, according to a State Department official.

And in early August 2015, US ambassador Derek Mitchell talked with Min Aung Hlaing, commander-in-chief of the Myanmar military, and asked the leader whether the country had retained a small stockpile of sulfur mustard. According to the State Department’s recent unclassified report, Mitchell requested that the country investigate the issue and inform the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, which oversees the Chemical Weapons Convention, about the program.

But, as the State Department’s non-compliance report recounts, Myanmar’s initial declaration to the organization on September 7, 2015, didn’t mention the former weapons program. Myanmar didn’t declare possession of chemical warfare agents or a chemical weapons production facility. Despite years of denial, there are now signs that the country may finally be willing to grapple with its past chemical weapons activities.

Last November, US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Thomas DiNanno publicly called out Myanmar before the diplomats and chemical weapons experts attending the annual meeting of representatives to the Chemical Weapons Convention. The speech seemed to have its intended effect, as later, Myanmar’s Ambassador Kyaw Moe Tun reiterated his country’s commitment to complying with the treaty and, in reference to the US allegations, said his country was “always willing and ready to address any concern raised in this regard in a constructive manner.”

In January, Myanmar accepted a standing US offer to send a delegation of experts for consultations, marking the first time the country has been willing to discuss concerns about violations of the treaty. It’s likely that Myanmar’s military, given its continued role in government, approved of the invitation, an important indication that the civilian government may be able to not only declare the past program, but also offer the level of transparency and cooperation necessary for the Organization for the Prohibition on Chemical Weapons to verify any future declaration by Myanmar and ensure that remnants of the program are destroyed. In late February, a US delegation traveled to Yangon for “productive” talks, according to a State Department official.

Why now? While it’s difficult to say why Myanmar is finally signaling a willingness to address its chemical weapons, what is clear is that despite the glowing press coverage in the mid-2010s surrounding the country’s efforts to rejoin the world community, Myanmar’s star on the world stage has since dimmed. Suu Kyi, once an inspirational figure the world over, not only failed to stop the violence against the Rohingya, but justified these acts. A United Nations Fact-Finding Mission reported last September that Myanmar’s military campaign against minority groups amounted to crimes against humanity. What the fact-finding mission calls a “clearance operation” against the Rohingya in 2017 caused at least 10,000 deaths and sent another 725,000 Rohingya fleeing to neighboring Bangladesh. Two months after the report, the International Criminal Court, an organization whose mandate includes prosecuting crimes against humanity, announced that it would investigate allegations that the Rohingya were forcibly displaced from Myanmar and persecuted because of their religion. The judicial arm of the United Nations, the International Court of Justice, meanwhile, ruled in January that Myanmar’s actions posed a sufficient risk of violating the Genocide Convention, and the court took the unprecedented step of ordering Myanmar to take active measures to protect the Rohingya, preserve evidence of genocide, and provide progress reports to the court.

Perhaps the Myanmar government views coming into full compliance with the chemical weapons treaty as a relatively easy way to show that it still hopes to play a part in the international community–Myanmar’s program, after all, is believed to be inoperative.

There’s still time for Myanmar to open up about its weapons program. It’s not unheard of for countries to declare chemical weapons programs years after joining the Chemical Weapons Convention. Ten years after ratifying the treaty, Albania announced its discovery of 16 tons of sulfur mustard obtained from China in the 1970s. The stockpile, it claimed, was forgotten in the transition from Communism to democracy. The United States and European countries helped Albania destroy this stockpile in 2007, enabling Albania to become the first treaty member to entirely eliminate its declared stockpile. In 2011, the transitional government in Libya informed the treaty organization that it had discovered two tons of chemical warfare agents and hundreds of chemical munitions that the previous government of Libyan strongman Muammar Gaddafi had not included in its original 2004 declaration. Again, the international community helped the country dismantle and destroy the program.

The allegations against Myanmar are only the latest challenge to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, and Myanmar’s alleged non-compliance is probably the most tractable item on this list for the organization to address. Since Syria joined the Chemical Weapons Convention in September 2013, the treaty organization has struggled to verify the destruction of that country’s chemical weapons capabilities, or, for that matter, address its repeated use of chemical weapons. In 2018, Russia used a novichok nerve agent in an attempted assassination of a former Russian spy living in the United Kingdom, another case in which the organization has had trouble taking decisive action. The United States has also accused Iran of violating the chemical weapons treaty, but has not sought to address the allegations through any formal process.

Next steps. By showing that it may open up about its past chemical weapon program, Myanmar is offering the United States an opportunity the Trump administration shouldn’t let slip. Washington should make it clear that it will provide the assistance—technical and financial—necessary for Myanmar to declare and destroy its program, perhaps by establishing a trust fund through the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Other countries should make similar pledges to Myanmar as a way of reassuring this developing country that the international community will help it shoulder the burden. Finally, the United States should make it clear that it views any chemical warfare agents, munitions, or production equipment that still exist at Tonbo to be a potential proliferation risk, thereby keeping this issue on the international agenda until it is fully resolved.

While the US allegation of Myanmar’s violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention revolves around a long-dormant program, the international community must take this case of potential non-compliance seriously. At the same time, Myanmar should seize the opportunity to come clean. The mission to rid the world of chemical weapons relies on all the parties to the weapons treaty adhering faithfully to it.

Even if they do so belatedly.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.