Students on lockdown create a global guide to coronavirus conspiracy theories, fake cures, and other whopping lies

By Matt Field | May 26, 2020

Disinformation has been spreading in numerous languages and countries as society grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Disinformation has been spreading in numerous languages and countries as society grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic.

In late February, Luca Zanotti was in Milan finishing his last year of college at Bocconi University when the number of COVID-19 cases began to explode in Italy. The political science student had to return to his hometown, Cesena, to finish the semester online while on lockdown. Since then Italy’s outbreak has begun to subside, but 21-year-old Zanotti still doesn’t know if he’ll be able to return to Milan to start graduate school in the fall; a resurgence of the coronavirus could upend any post-summer plans.

The pandemic has left many people simply waiting for what comes next—for employers or schools to tell them to come back, or for officials to adjust public health orders. Amid all this waiting, Zanotti and a group of about 20 college and graduate students has found a way to move forward. They’re tackling one prominent aspect of the pandemic—rampant disinformation—head on. “It’s kind of a weird way to give our contribution to this crisis,” Zanotti said, but armed with a coding manual, he and the others have been rigorously cataloguing hundreds of disinformation narratives circulating in Italy, Syria, Japan, and elsewhere.

They’re logging all the lies, conspiracy theories, and misleading political attacks that have seemingly spread as fast as the virus itself. In this pandemic era, issues that seem entirely within the purview of empirical research are instead being hotly debated outside of scientific forums. How effective a person in the United States thinks the drug hydroxychloroquine is as a COVID-19 treatment may have more to do with how he or she votes than the results of any study. Adding just a little clarity to this muddled picture definitely isn’t weird; it’s important work.

Zanotti has spent almost three months at home—near a beach on the Adriatic Sea he hasn’t been able to go to, far from a girlfriend in a different region he can’t visit, and upstairs from a grandmother he can’t hug. One thing he can do is try to keep track of the disinformation coursing through the Italian internet. “In Italy, where the public debate is really affected by social media, the amount of fake news going on in social media is amazing,” he said.

From her home in Portland, Oregon, Fumika Mizuno, a Princeton University junior, has been monitoring disinformation in Japan. Like students elsewhere, Princeton students have been taking classes online. “I felt very helpless. I felt like, being stuck at home, I really wanted to contribute in some way, whatever it was,” she said. “I speak Japanese, and I thought this would be a really great way to contribute in a small way and also to learn more about disinformation narratives in Japan.”

Like Mizuno, many of the student researchers attend Princeton. Others come from Bocconi University, The University of Chicago, and Columbia University. They’ve been updating a project spreadsheet–so far more than 800 entries long–that lists all of the disinformation narratives they’ve found spreading in countries around the world. Princeton Professor Jacob Shapiro, the co-director of Princeton’s Empirical Studies of Conflict Project, and Jan Oledan, a research specialist for the project, kicked off the disinformation tracking effort in March. “We weren’t seeing any place where things from multiple countries were really pulled together,” Shapiro said.

The researchers comb social media and the internet, including the fact-checking sites that have cropped up around the world, and use a coding manual to characterize the type of stories they find. An email circulating in the Czech Republic about how the United States supposedly “registered” the coronavirus in 2003 (it didn’t) in order to attack China? According to the student researchers, that’s a “weaponization or design” story. A chain message on the messaging platform Line falsely claiming that Japan would go into a nationwide lockdown on April 1? That one is labeled an “emergency response” narrative.

Looking at the team’s data, a few storylines appear over and over again—like the false conspiracy theory that the disease is some kind of weapon. Frequently these tales take on a local flavor. In Syria, for instance, social media posts were circulating that claimed COVID-19 was the product of US sarin gas experimentation in Afghanistan. Given the many allegations of chemical-weapons use that have surfaced during the Syrian civil war, it’s perhaps not surprising that sarin gas would factor in local conspiracy theories about COVID-19. In another narrative, a Facebook user alleged that European countries were spreading the virus to Egypt by exporting their “gently used” infected clothing. An overlay on the post indicated Facebook had flagged it as false.

COVID-19 disinformation often seems to target a country’s foreign or minority population. The Princeton team reported that the influential Nepali journalist Rajendra Dahal speculated on Twitter last month about the “role of Muslims in spreading COVID-19” and about why they are “hiding” in mosques. Nepali media have reported on rising Islamophobia following several positive cases among Muslims in the country. Likewise, in Japan, social media users have pushed the false information that “one third or half of Japan’s coronavirus cases are [among] non-citizens.”

What do cocaine, sex, and whiskey have in common? At the very least, they have all been part of disinformation narratives on how to treat or prevent COVID-19, according to the Princeton data. The team found dozens of examples of fake cures being promoted in countries around the world. In one instance, Indian politicians claimed that Britain’s Prince Charles, who earlier this year self-isolated after testing positive with COVID-19, had treated himself with homeopathy and Ayurvedic medicines, a claim that Indian media sources said the prince’s spokesperson denied.

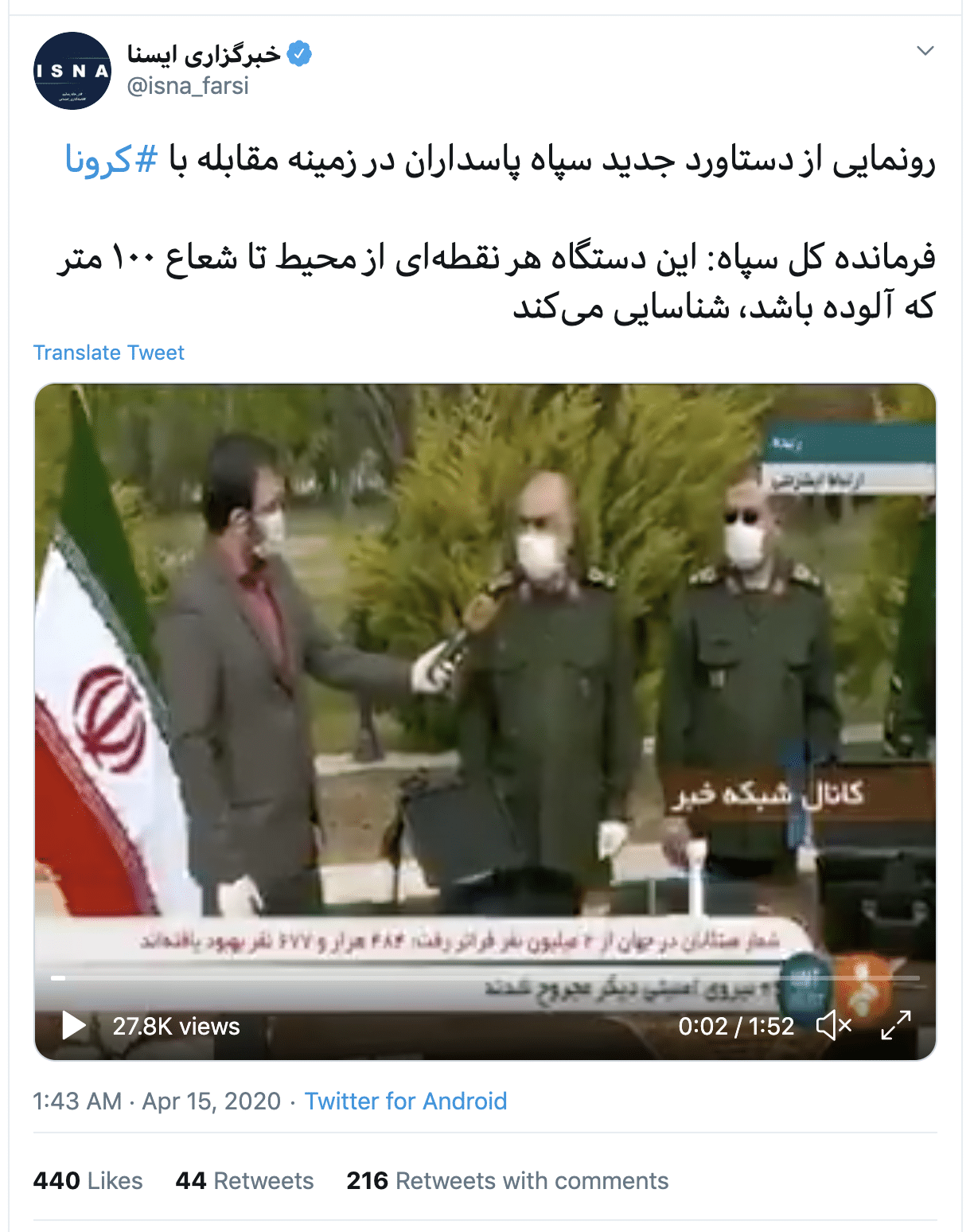

In an example of how some promoters of false information have highlighted fake progress in the battle against the pandemic, the Iranian news agency ISNA tweeted a video showing a member of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps discussing a novel technology that can detect coronavirus infection from 100 meters away. The Princeton team concluded that the video is an attempt to make the “Iranian government look responsive” and innovative.

And the coronavirus appears to factor heavily in many politically motivated posts. In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte won praise for his COVID-19 response from none other than Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II herself, at least in some of the blatant disinformation spreading on Facebook. The false posts had the queen praising Duterte as someone who “knows the way, goes the way, and shows the way,” according to Rappler, a news website in the Philippines.

Oledan, who is managing the Princeton project, said that when team members first started compiling narratives in March, they were finding a lot that had to do with false cures. The team is finding fewer false cure narratives these days. Once governments started imposing lockdowns, a lot of the disinformation the team was seeing focused on the emergency response.

Much of the team’s work draws on investigations by the network of fact-checking websites that now exist in many countries around the world. The stories, however, are often not in English; the researchers’ language abilities allow them to access these sources of information and combine them in one English-language data set. “We’re really kind of crowdsourcing a lot of these local fact-checking websites and resources and using these to our advantage,” Oledan said.

As of May 21, the latest narrative entered on the spreadsheet was number 872: An advisor to the health ministry in Nepal had been attempting to “downplay the truth of how many infected patients Nepal’s public health infrastructure can realistically handle,” according to the team’s description.

It is just one of many emergency response narratives that seek to minimize the severity of the COVID-19 crisis. When the Princeton team wraps up, most likely in September, they will have compiled a pretty comprehensive global data set of these disinformation plots. “I think the biggest contribution that we wanted to make was to create a resource that others could go to, in order to identify the different areas and stories that were out there,” Shapiro said.

Researchers, historians, journalists, and others will inevitably be analyzing the pandemic for a long time to come. Some of the narratives the Princeton team has compiled seem trivial, others outlandish, some even dangerous; all together, they help tell the story of strange and inaccurate communication in a strange and dangerous era.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Disinformation

Topics: Disruptive Technologies