The anatomy of a STRATCOM disinfographic

By John Krzyzaniak, Thomas Gaulkin, May 7, 2020

United States Strategic Command, the branch of the US military responsible for the nation’s nuclear weapons, recently released an imperially misleading infographic on Twitter. The graphic is confused—not only about when to use bold typeface, but also about the facts.

“The threats we face today and in the future are real, and have not changed during the pandemic. While we continue to seek and provide for a safe and secure world, others continue to act provocatively and irresponsibly.” - ADM Richard pic.twitter.com/8RJXS10ZE9

— United States Strategic Command (@US_STRATCOM) May 3, 2020

The Bulletin’s editorial team has annotated the graphic as a service to readers.

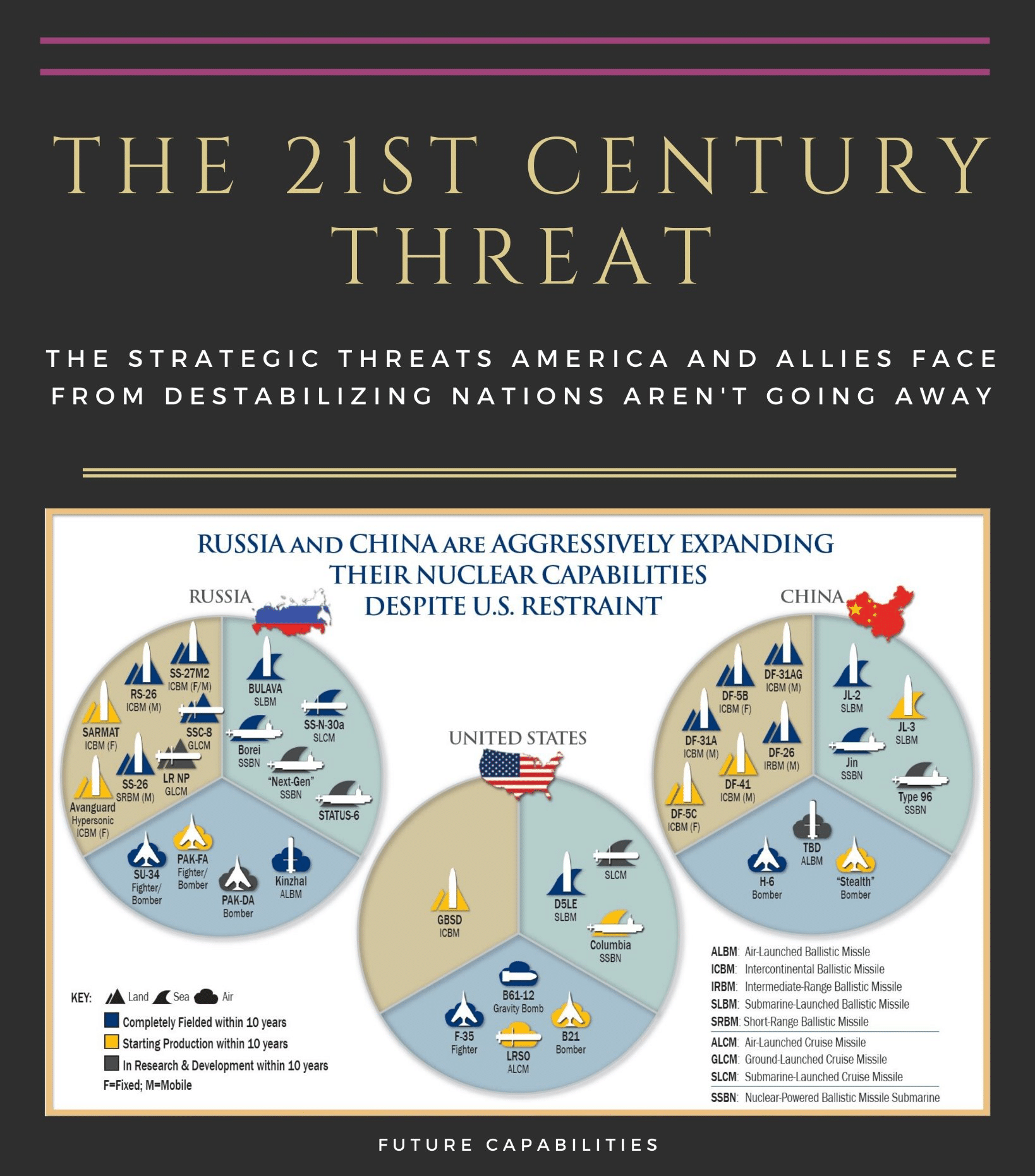

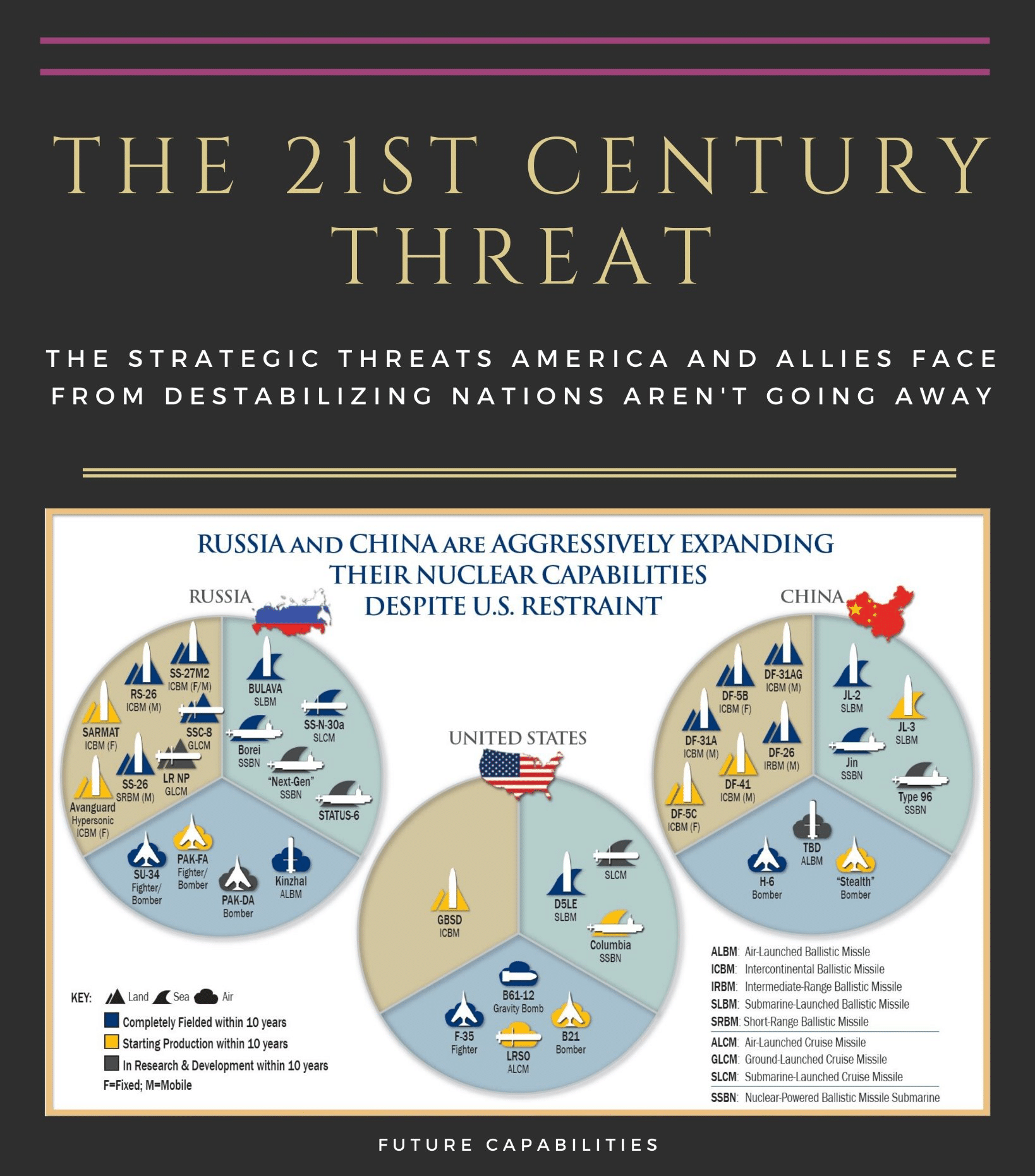

The first section purports to show how China, Russia, and the United States will be upgrading their respective nuclear forces over the coming years. The graphic is hard to decipher, not least because it contains many acronyms, mixes strategic and tactical systems, and commingles NATO’s naming system with indigenous ones.

The Department of Defense spends $700 billion per year to protect the American people, but it was unable to do anything to stop the coronavirus pandemic. US officials may need to revisit how they prioritize 21st century threats. (Design note: The typeface deployed appears to be an imitation of Trajan, a font inspired by imperial Rome and used to promote countless Hollywood epics.)

The definition of such nations may be in the eye of the beholder. Recent US actions—like withdrawing from the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran and from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with Russia—have themselves been characterized as destabilizing.

Some would say "restraint" is not accurate terminology. The United States is projected to spend $1.2 trillion to $1.7 trillion over the next 30 years on its nuclear modernization program.

Quantities matter. These pie-charts suggest the Chinese and Russian arsenals are exploding. But more types of things does not necessarily mean more things overall, or that the things represent greater capabilities. Several of the systems shown here (like China's DF-41) will replace older systems with comparable capabilities.

The chart omits the US W76-2 warhead, a submarine-launched "low-yield" nuclear weapon first deployed near the end of 2019. Since this warhead already exists, it may not precisely fit this chart's focus on "future capabilities"; still, it is a new and highly controversial device that critics argue increases the potential for a nuclear exchange with Russia.

This piece of the pie slyly gives the impression that US ground-based weapons development is trivial compared to what appears in the adjacent charts. But this single icon represents a new intercontinental ballistic missile program that will eventually dwarf China's entire nuclear arsenal.

The graphic does not indicate which systems will phase out or replace others. For example, the Sarmat will likely replace the SS-18, not mentioned on this graphic, on a less than one-to-one basis. The SS-27M2 is also being deployed as other systems are retired.

The Avangard missile (misspelled here as "Avanguard") is mislabeled as a "hypersonic ICBM." Avangard is currently deployed on top of SS-19 ICBMs, but it is not one by itself. All ICBMs are technically hypersonic because they travel at speeds in excess of Mach 5.

The Department of Defense spends $700 billion per year to protect the American people, but it was unable to do anything to stop the coronavirus pandemic. US officials may need to revisit how they prioritize 21st century threats. (Design note: The typeface deployed appears to be an imitation of Trajan, a font inspired by imperial Rome and used to promote countless Hollywood epics.)

The definition of such nations may be in the eye of the beholder. Recent US actions—like withdrawing from the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran and from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with Russia—have themselves been characterized as destabilizing.

Some would say "restraint" is not accurate terminology. The United States is projected to spend $1.2 trillion to $1.7 trillion over the next 30 years on its nuclear modernization program.

Quantities matter. These pie-charts suggest the Chinese and Russian arsenals are exploding. But more types of things does not necessarily mean more things overall, or that the things represent greater capabilities. Several of the systems shown here (like China's DF-41) will replace older systems with comparable capabilities.

The chart omits the US W76-2 warhead, a submarine-launched "low-yield" nuclear weapon first deployed near the end of 2019. Since this warhead already exists, it may not precisely fit this chart's focus on "future capabilities"; still, it is a new and highly controversial device that critics argue increases the potential for a nuclear exchange with Russia.

This piece of the pie slyly gives the impression that US ground-based weapons development is trivial compared to what appears in the adjacent charts. But this single icon represents a new intercontinental ballistic missile program that will eventually dwarf China's entire nuclear arsenal.

The graphic does not indicate which systems will phase out or replace others. For example, the Sarmat will likely replace the SS-18, not mentioned on this graphic, on a less than one-to-one basis. The SS-27M2 is also being deployed as other systems are retired.

The Avangard missile (misspelled here as "Avanguard") is mislabeled as a "hypersonic ICBM." Avangard is currently deployed on top of SS-19 ICBMs, but it is not one by itself. All ICBMs are technically hypersonic because they travel at speeds in excess of Mach 5.

The overall impression, though, is that Russia and China will be rolling out many more new systems than the United States over the coming years, and so the danger to “America and allies” is growing.

But that’s wrong for several reasons. First, the chart is not making an apples-to-apples comparison. Although it purports to show “future capabilities,” it includes many Russian and Chinese weapons that are already partially or mostly deployed, while conveniently omitting deployed US weapons.

Second, more systems does not equate to more capabilities. Many of the systems shown, such as Russia’s Sarmat, the United States’ GBSD (Ground Based Strategic Deterrent), and China’s DF-41, are slated to replace older systems that have broadly similar capabilities. Moreover, in at least one place the chart duplicates two versions of the same system. The Pentagon has described China’s DF-31AG as simply “an enhanced version of the DF-31A,” but they appear as separate systems on the chart. Even where systems are entirely new, they will hardly alter the overall strategic balance.

Third, the chart gets the size of the pies wrong—it doesn’t say anything about how many of each system will be built. For example, it shows two icons for Chinese submarines and only one icon for US submarines. But China will likely build at most six of each type. The United States, meanwhile, plans to build 12 Columbia-class submarines.

Similarly, the United States plans to build more than 400 land-based missiles through its GBSD program, so that single icon in the pie chart will represent far more intercontinental ballistic missiles than China will have in its entire arsenal.

Overall, while all three countries are in the midst of expansive (and expensive) nuclear modernization programs, the United States has a nuclear arsenal that is more than adequate, and it will remain so over the coming decades.

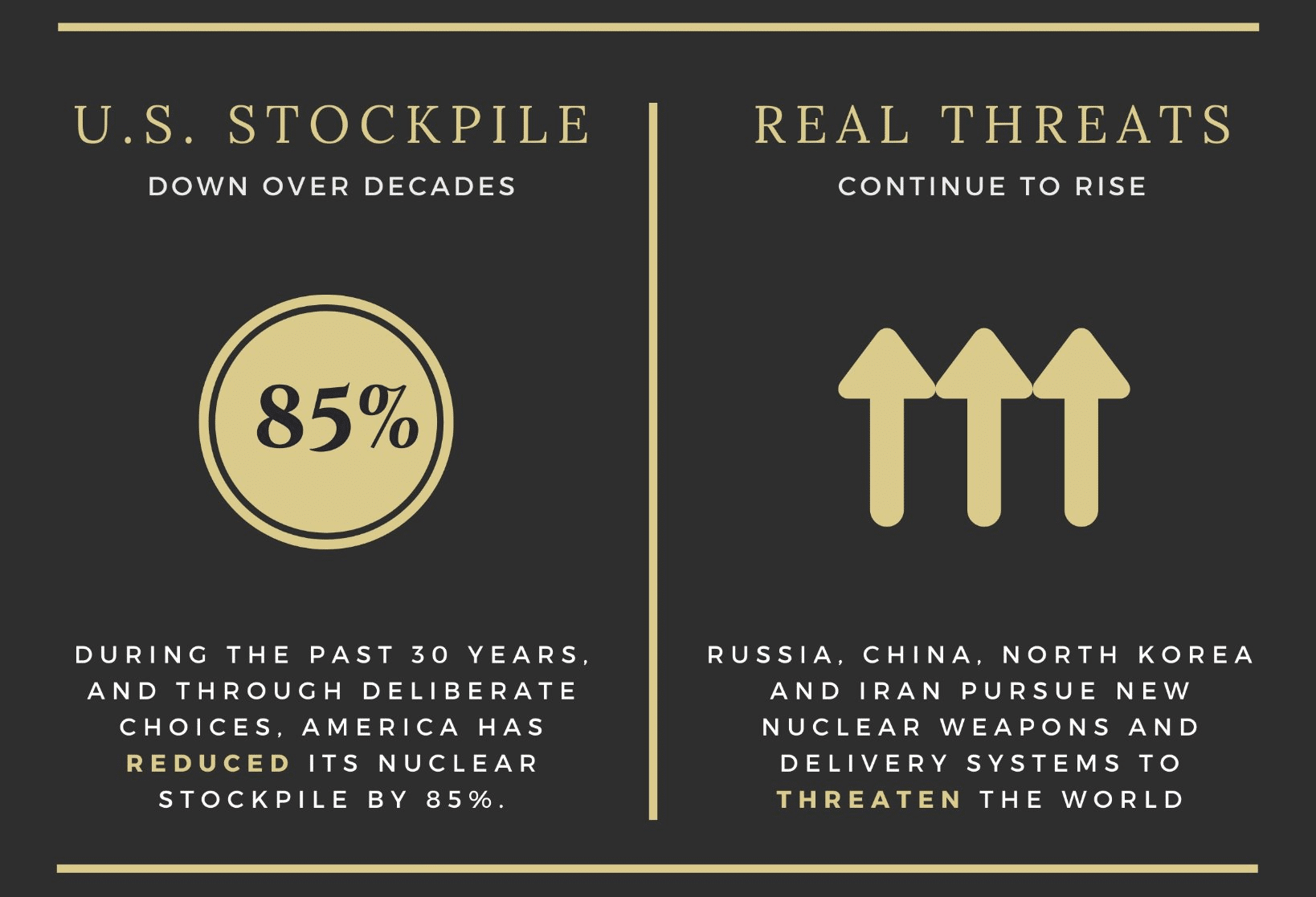

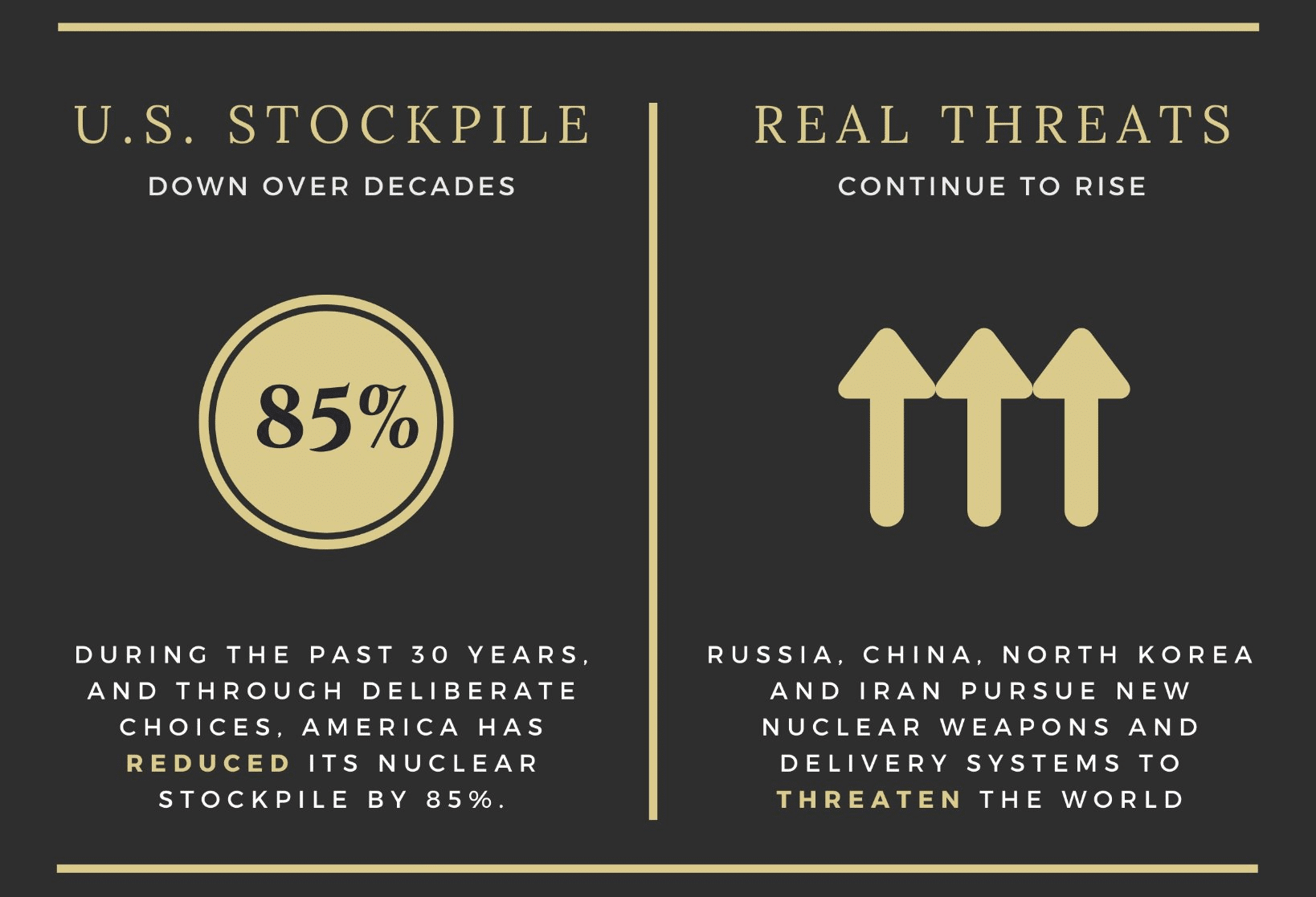

According to the Bulletin's Nuclear Notebook, the US stockpile decrease from 1990 to 2020 was more like 82 percent. Regardless, since the goal of the graphic is to distinguish US reductions in its nuclear arsenal, it conveniently omits that Russia has reduced its stockpile by 88 percent over the same period.

Not mentioned: These "deliberate choices" were most often the result of years of diplomatic negotiation, agreement, and bilateral treaties between the United States and Russia.

Iran does not have nuclear weapons, and although there is evidence that it pursued building a nuclear weapon in the past, it ceased that work in 2003 and has not resumed it.

According to the Bulletin's Nuclear Notebook, the US stockpile decrease from 1990 to 2020 was more like 82 percent. Regardless, since the goal of the graphic is to distinguish US reductions in its nuclear arsenal, it conveniently omits that Russia has reduced its stockpile by 88 percent over the same period.

Not mentioned: These "deliberate choices" were most often the result of years of diplomatic negotiation, agreement, and bilateral treaties between the United States and Russia.

Iran does not have nuclear weapons, and although there is evidence that it pursued building a nuclear weapon in the past, it ceased that work in 2003 and has not resumed it.

The second section of the infographic juxtaposes a decrease in the US nuclear stockpile on the left with an increased threat level on the right. This section, too, is full of inaccuracies.

For instance, the assertion that the US stockpile has decreased by 85 percent in the last 30 years is slightly off. According to the authoritative Nuclear Notebook, the United States has reduced its stockpile from around 21,400 warheads in 1990 to around 3,800 in 2020, an 82 percent decrease.

More important, there’s no mention of Russia’s dramatic reductions, which have outpaced those of the United States. Since 1990, the Russian stockpile has declined from roughly 37,000 warheads to 4,310—an 88 percent decrease. So it is not as though US reductions were unilateral—quite the opposite. (China, with perhaps 300 warheads, is not likely to make any reductions until Russia and the United States reduce their own stockpiles further.)

It is true that the United States has reduced its stockpile through “deliberate choices” over the decades. Scholars and policymakers have long understood that arms racing makes all sides less safe, while arms control can make war less likely. The fact that mutual nuclear arms reductions have enjoyed bipartisan support in the United States for longer than 30 years should be a strong signal that this is sound policy.

Serif or sans-serif? The typographic indecision of this section's title reflects the ambiguity pervading the entire graphic—is the United States unmatched among its nuclear peers? Or is it a victim?

Russia’s Avangard and Sarmat weapons may not fall outside the limits of the New START treaty. The new Chinese systems don't violate any arms control agreements either—since it's not a party to any. And the United States has bypassed treaty obligations its own way—by simply canceling them. Just two weeks after it withdrew from the INF Treaty, the US tested missiles the treaty would have prohibited.

The US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and its reimposition of sanctions are viewed as aggressive even by European allies. When Iran went to the International Court of Justice alleging violations of US obligations under international law, the White House refused to acknowledge the jurisdiction of the court and then withdrew from the disputed treaty for good measure.

Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea have all tested weapon systems over the past few months. But so has the United States, which launched a Minuteman III ICBM from Vandenberg air force base on February 5, and tested a hypersonic glide body in Hawaii on March 19.

As recently as April 17, the US State Department told Congress that Russia continues to abide by the New START treaty, which expires next year. Russia has offered to extend New START another five years without preconditions, but the White House has yet to agree.

Serif or sans-serif? The typographic indecision of this section's title reflects the ambiguity pervading the entire graphic—is the United States unmatched among its nuclear peers? Or is it a victim?

Russia’s Avangard and Sarmat weapons may not fall outside the limits of the New START treaty. The new Chinese systems don't violate any arms control agreements either—since it's not a party to any. And the United States has bypassed treaty obligations its own way—by simply canceling them. Just two weeks after it withdrew from the INF Treaty, the US tested missiles the treaty would have prohibited.

The US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and its reimposition of sanctions are viewed as aggressive even by European allies. When Iran went to the International Court of Justice alleging violations of US obligations under international law, the White House refused to acknowledge the jurisdiction of the court and then withdrew from the disputed treaty for good measure.

Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea have all tested weapon systems over the past few months. But so has the United States, which launched a Minuteman III ICBM from Vandenberg air force base on February 5, and tested a hypersonic glide body in Hawaii on March 19.

As recently as April 17, the US State Department told Congress that Russia continues to abide by the New START treaty, which expires next year. Russia has offered to extend New START another five years without preconditions, but the White House has yet to agree.

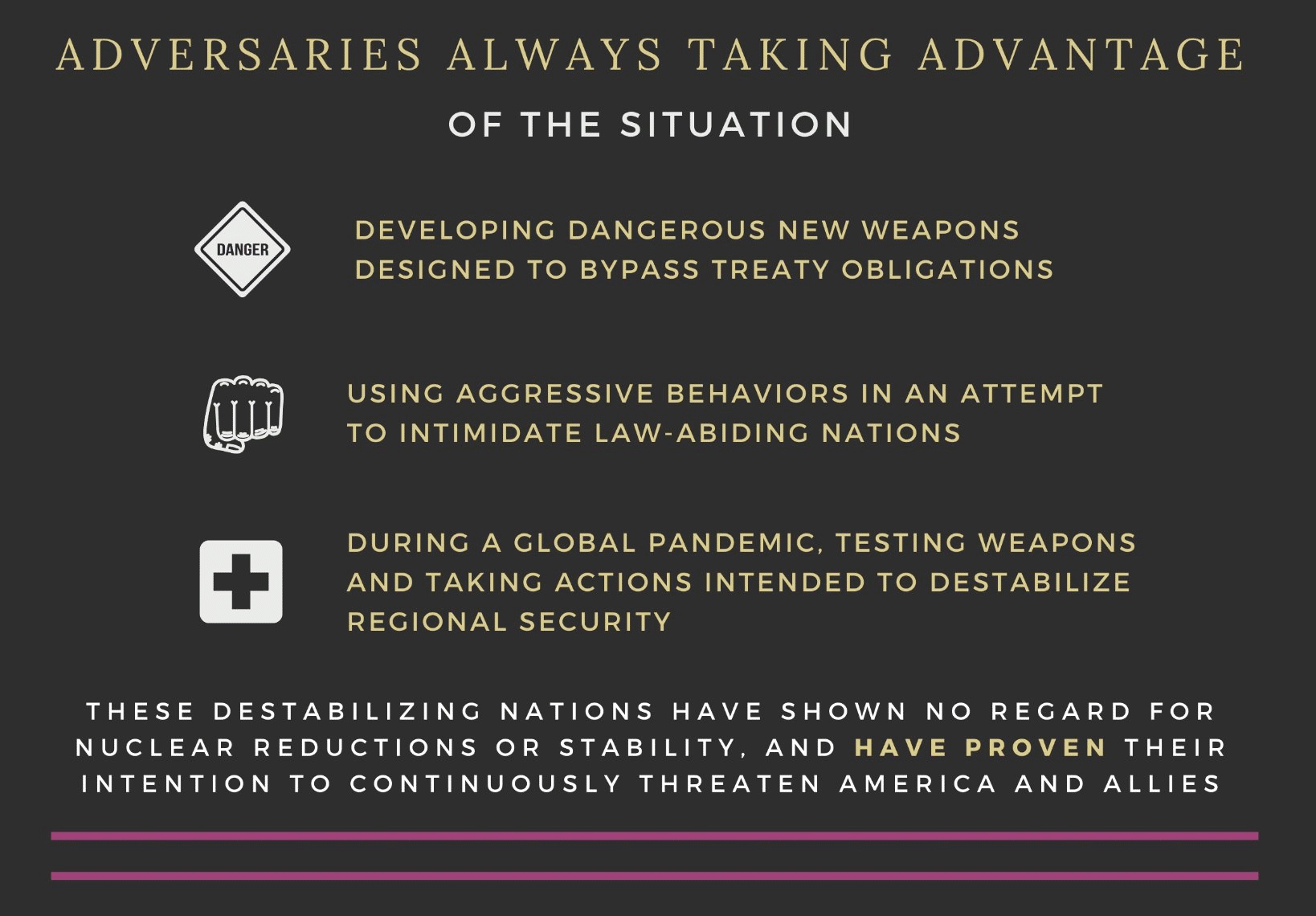

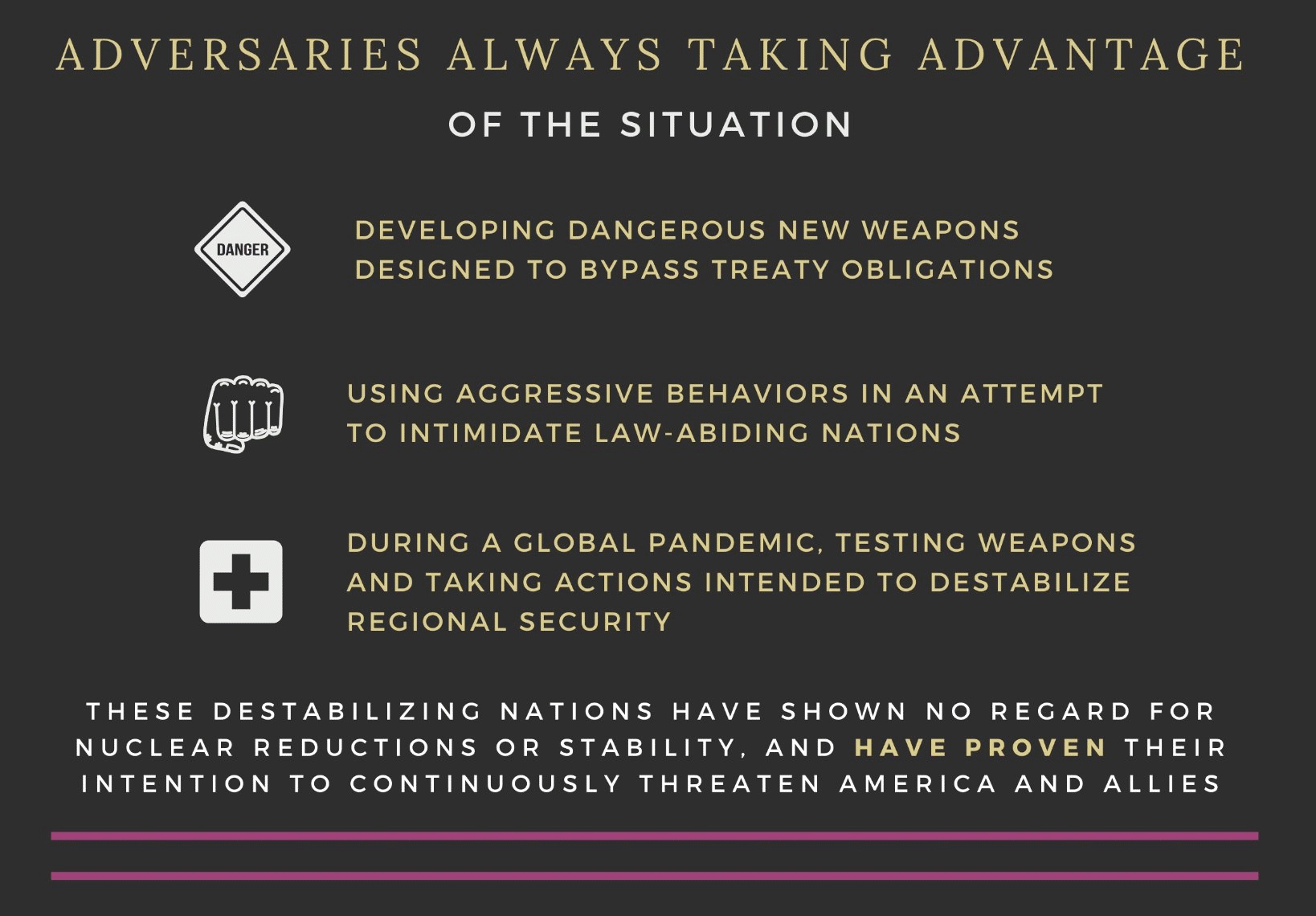

The final section paints a picture of a law-abiding United States victimized by rogue countries that are “taking advantage of the situation.”

It suggests that China and Russia are developing new weapons that will “bypass treaty obligations.” This may be true for some of the more fanciful Russian systems under development. However, others, such as the Avangard and the Sarmat, can be incorporated into New START—the relevant existing treaty—quite smoothly. For China, none of the new systems listed above will violate or bypass any treaty, because no such agreement exists.

Meanwhile, the graphic makes no mention of agreements from which the United States has withdrawn, in some cases against the counsel of its allies. The Trump administration withdrew from the INF treaty in August 2019 and quickly began working on a weapon that the treaty would have banned. So although the Russians may have been guilty of breaking the law, the United States did one better by eliminating the law itself.

And although the 2015 nuclear deal between Iran and major world powers was a political agreement rather than a legally binding treaty, it was the United States that withdrew and reimposed sweeping sanctions on Iran. So there would be little basis for claiming that Iran is “using aggressive behaviors” to “intimidate” the United States—rather, the opposite may be true.

There’s truth to the assertion that China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia have all tested weapons over the last several months, even as the entire world grapples with the COVID-19 outbreak. But so has the United States: It tested an intercontinental ballistic missile in February and a hypersonic missile glide body in March.

The final paragraph states that these countries “have shown no regard for nuclear reductions,” although by all accounts Russia, the United States’ main competitor in terms of nuclear arsenals, has abided by nuclear reduction agreements. In fact, it is the Trump administration that stands in the way of extending the only remaining agreement that would keep such reductions in place—New START. The Russians are ready to extend the treaty for five years without imposing or even discussing new conditions.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: STRATCOM, infographics, nuclear arsenals, nuclear modernization, propaganda

Topics: Multimedia, Nuclear Weapons

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

I am a recently retired NNSA nuclear weapons program manager. Like many in the nuclear-strategic community, I’ve been confident that our honest, sober and competent military leaders had a a firm grip on reality and could be relied upon to reject the the delusions of our narcissism-obsessed fact-free political leadership. Now I see how gullible we’ve been. This STRATCOM disinforgraphic is remarkable not just for its specific lies. It’s most memorable for its overall threat-hyping thrust which is straight out of the Politburo-style”Soviet Military Power” propaganda books of the early Reagan era. Back then, military officers privately ridiculed such hype… Read more »

I had some dealings with DOE as a union H&S official, back in the 1994-2000 era when there was more openness (or attempts at that) over issues such as surplus civilian plutonium and what to do with it, workers health and safety oversight for the nuclear weapons and labs complex, cleanup, etc. Even then, the frustration of folks in DOE over some of the controls some agencies excercized over DOE being able to talk about civilian stockpiles was clear. Related was the power which the contractors operating the weapons manufacturing facilities and national labs had on determining their own bonuses.… Read more »