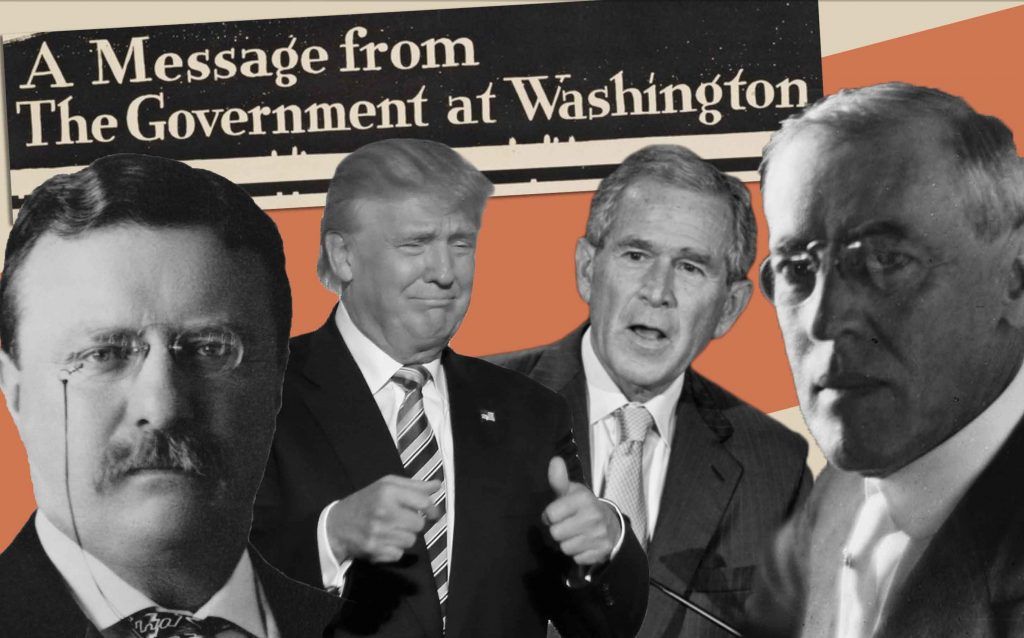

Sad! A brief history of White House propaganda from Teddy Roosevelt to Donald Trump

By John Maxwell Hamilton, Kevin Kosar | November 12, 2020

Illustration by Matt Field/Ffitzsimons/Spartan7w. Creative Commons.

Illustration by Matt Field/Ffitzsimons/Spartan7w. Creative Commons.

Since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, our leaders have had the duty to draw on the government’s public health expertise and vast trove of data on COVID-19 to both explain the threat and teach us practices to diminish the damage it can cause. Instead, President Donald Trump downplayed the virus, likening it to seasonal influenza and saying it would go away by Easter. He sent conflicting messages about the value of shutdowns, social distancing, and masks. He used White House pandemic briefings to show videos that were blatant advertisements for his presidential campaign.

In the final days of the campaign, when infection rates were going up, Trump’s science office briefly made the preposterous claim that the administration’s greatest accomplishment was ending the pandemic.

For the United States, the pandemic has been an information crisis as much as a medical one. “Science is on the ballot,” Jennifer Doudna, the newly minted Nobel Prize laureate, said of the presidential election. There is truth to this, but the lessons to be learned from this fiasco extend beyond the pandemic.

For over a century the ability of the chief executive to shape our thinking has grown steadily with little attempt to check its pernicious aspects. The pandemic shows a corrective is long overdue.

The many shades of government information. The control of propaganda is one of the thorniest problems of democracy, depending on how it is administered, government information can sustain democracy or undermine it.

In the early history of the country, the White House did not think much about making news. There were no presidential press spokesmen and no press releases. Early presidents saw Congress as their primary audience. Legislators, for their part, saw themselves having the closest link with voters’ opinions. The White House’s use of information began to change under President Theodore Roosevelt, the first to use the new technique of press releases. Resentful, Congress passed laws forbidding executive agencies from hiring “publicity experts.”

But Roosevelt’s press releases were just an early chapter in the story of presidential propaganda.

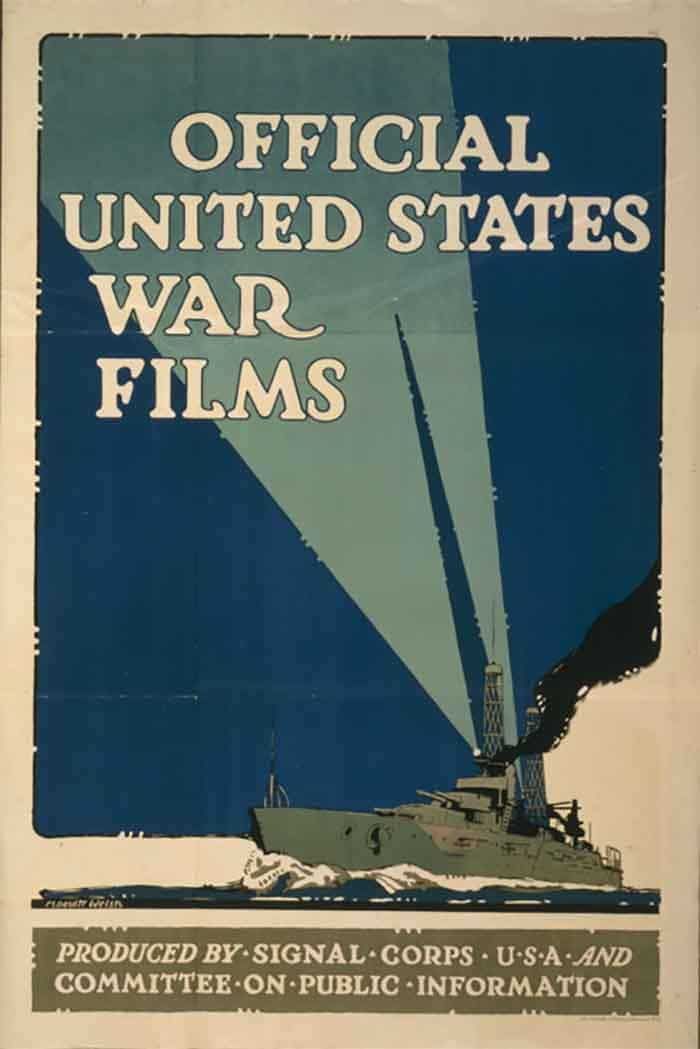

During World War I, Woodrow Wilson built support for the war effort in part by establishing systematic, pervasive propaganda as a quotidian instrument of the state. Its agent for this was the Committee on Public Information (CPI), which represented the first and only time the US government had a ministry of propaganda.

The range of the CPI’s activities is stunning even by today’s standards. “There was no part of the great war machinery that we did not touch, no medium of appeal that we did not employ,” George Creel, the CPI’s chief, said. It was one of the few times the hyperbolic former journalist made an understatement.

The CPI established a national newspaper, the Official Bulletin, and filled war-making agencies with press officers who cranked out news releases and guided reporters. Officials spread the CPI’s messages through articles, cartoons, and advertisements in newspapers and magazines; through textbooks and Sunday church sermons; through feature films and ads on theater curtains; through posters plastered on buildings and displayed in store windows; and through pamphlets distributed by the millions.

The CPI also established a news service to get the American point of view to foreign audiences. It created the first public affairs offices in conjunction with US embassies abroad. To a degree never before seen with presidential pronouncements, the government publicity effort promoted Wilson’s post-war agenda—and the president himself—through films, posters, and speakers.

Indicative of the CPI’s creativity was its Four Minute Men program. These volunteers spoke in movie theaters as movie reels were changed. By the end of the war, the CPI had marshalled 75,000 of these carefully scripted local opinion molders.

Much of CPI’s propaganda and its offshoots might be considered wholesome.

Public diplomacy is an important foreign policy tool. The Official Bulletin became the antecedent for the Federal Register and other organs that give transparency to government work. And who can object to the US Forest Service having Smokey the Bear reminding the public not to inadvertently set forest fires?

At the same time, though, the CPI was coercive and appealed to the emotions of hate and fear. Although it claimed to work openly, the CPI created front organizations and secretly subsidized newspapers overseas. While Wilson claimed to believe in free debate, the CPI sought to stifle inconvenient opinion. What Trump calls “fake news” was, in the Wilson administration, “enemy talk.”

Although the CPI was dismantled at the end of World War I, its techniques and functions have carried on through public affairs offices in individual departments and agencies, and in an ever-expanding White House communications apparatus. All this is buttressed by increasingly sophisticated techniques for analyzing public attitudes and changing them.

The president’s modern “propaganda” operations. America’s once modest executive branch has ballooned in size. One upside to this development is that the federal government has become a treasure chest of information. Businesses can track trade flows. Communities can be alerted to impending hurricanes. Parents can get evidence-based facts on childhood nutrition.

While data collection and analyses are valuable, presidents have been tempted to abuse the executive branch’s swelling communications operations.

It is one thing for presidents to go out and argue for their policies; their speeches, interviews, and meetings are an essential component of democracy. But it is quite another for a president to use the public affairs office of a taxpayer-funded federal department to change views, rather than inform, or to close the spigots of government information in order to deceive.

Trump has shown how this power can be deployed for personal ends. He has insisted on putting his name on coronavirus relief checks. He has blocked the release of scientific studies that help us understand the consequences of global warming.

But Trump is not the only president to take advantage of the communication powers that lay in easy reach. President Barack Obama’s administration unleashed a $700 million public relations blitz for his health care law. The George W. Bush and Clinton administrations tried to sell their Medicare initiatives by releasing TV news style videos that used PR staff posing as reporters interviewing government officials and doctors. In some cases, unsuspecting broadcast media ran them as if they were legitimate news. A government watchdog report found that some of the videos violated federal publicity and propaganda rules.

A federal department’s communications resources should be spent on informing, not persuading or manipulating.

Unfortunately, laws and rules to control such abuse are inadequate and rarely enforced. Consider, for instance, the century-old law banning the employment of “publicity experts.” This has been circumvented by using other job titles, such “health communications specialist.” This is not all bad. As noted, we need government officials to keep us informed.

But the ease with which the executive branch has slipped around rules makes it difficult to measure government investment in communications and public relations or to restrict the growth of those efforts. In addition to using misleading titles for communications staffers (the Truman administration, for instance, classified an Air Force public affairs officer as a chaplain) the government can contract with private communications firms.

Legislators have added prohibitions to annual spending bills to prevent the use of funds for “propaganda and publicity purposes not authorized by Congress.” But federal agencies answering to the president little heed these restrictions and regularly advocate for the president’s agenda.

Once in a while the Government Accountability Office (GAO) will flag an agency for spending funds for illicit propaganda, such as secretly paying journalists to write government propaganda. But no meaningful penalties result. The Department of Justice can merely disagree about the finding of wrongdoing, or the propagandizing agency can ignore GAO’s demand to repay the misspent money.

No executive branch official has ever been charged with breaking these laws.

Something needs to be done. We offer four important reforms to limit presidential information powers.

First, Americans deserve an audit of how much the government is spending on communications with the public, and an assessment of where the dollars are going. Data from USASpending.gov indicate executive agencies will spend nearly $1.4 billion on advertising contracts with private firms in 2020. But this grossly understates actual expenditures, as it excludes the government’s in-house costs, such as the compensation earned by the legions of communications staff across the executive branch, or the costs for operating the government’s innumerable blogs and YouTube channels.

The GAO has audited individual agencies, but Congress could direct it to look at all 170 federal agencies. While doing this, the GAO could also come up with a definition of “public communication” that all agencies would be required to use in accounting for their spending.

Nothing like that currently exists.

Second, Congress should appoint a bipartisan blue-ribbon commission to recommend improvements on antiquated laws on government communications. For instance, federal laws forbid agencies from using funds for unauthorized “publicity” or “propaganda” but fail to define these terms, or even hint at the differences between them and acceptable government communications.

The law against employing publicity experts, which was enacted in response to Theodore Roosevelt’s self-promotion, is useless. And the statute forbidding agency communications with the public is anachronistic. (Among other things, it forbids the use of telegrams, but not the internet.) Nor do any of these laws provide for any sort of punishment for violations. Not least, the panel should consider policies to stop agencies from spending funds to turn their spokespeople into media darlings.

This panel could also develop government-wide guidelines for agency public communications practices, which Congress could enact into law. Right now, agencies—with some direction from the White House’s Office of Management and Budget—are free to develop their own communications policies.

Uniform and publicly available standards should make clear what is expected of government agencies in their communications with the public. One standard might require that communications should be balanced and written in a tone that does not extol the agency or its activities.

Third, the commission needs to consider how we safeguard the data and science-based studies the government produces. The experts in our government are lynchpins of sound public opinion on a wide range of matters. Government experts are not infallible, but their views need to be publicly accessible, so they are weighed and debated intelligently.

Democracy is a project in openness, not control. In a larger sense, self-governance also is a learning process, one that is aided by public access to government information and data.

Fourth, White House press conferences and briefings need an overhaul. If treated seriously, they contribute to government accountability. As an example, many press secretaries reach out to executive departments to assess the issues of the day and identify the corresponding administration policy. After looking at the daily press briefing book, former President Bill Clinton was known to call a cabinet secretary to say a better policy was needed.

Under the Trump presidency, what was once a productive question-and-answer session has devolved into harangues. Beginning with Sean Spicer—who famously wouldn’t back down from patently false claims about the size of Trump’s inauguration crowd—the president’s press secretaries have been a parade of partisan spin doctors who treat the process with contempt.

The press is not without blame in this. Some journalists use the occasion of live broadcasts as a prime-time opportunity to enhance their brands by heckling the president or his spokespeople. The president would be doing the public a service by going back to the time, early in the Clinton administration, when press conferences were not broadcast live. But reform has to start with a president who sets a good example of respecting democratic processes, which is what is at stake.

Presidents may derive a degree of satisfaction from using propaganda to achieve their immediate goals. But the public and democracy suffer.

A byproduct of undemocratic propaganda is lack of faith in government, a trend that also can be traced to the Wilson administration’s Committee on Public Information.

The cynicism engendered by untoward presidential propaganda makes it more difficult for the government to function effectively. The needless controversies that have arisen from the flow of unreliable information put out by Trump have led many Americans to say they will not use a coronavirus vaccine when it is available: They simply don’t trust their government.

The pandemic is a clarion call to reform of our government information practices to align them with democratic principles. The public’s health and safety depend on it.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Committee on Public Information, Coronavirus, Donald Trump, propaganda

Topics: Disruptive Technologies, Opinion

Donald is just a symptom of a much worse problem.

Wilson didn’t just spout propaganda. He openly demonized US citizens of German descent (in fact, he railed against “hyphenated Americans”, claiming that they were ready to plunge a dagger into the heart of the republic). Never mind that he was a white supremacist who praised “Birth of a Nation”.

Hi John and Kevin – I would like to join your “team” and contribute what extra information I have found in researching this subject. A correspondent for the Boston Globe, Stephen Kinzer, has done extensive research on it. I’m half-way through his book: “The True Flag”, where he documents Teddy Roosevelt working with a politician named Lodge and a newspaper magnate named Hearst to flood the U. S. with propaganda in 1898, with the help of President McKinley. Their false claims that Spain sank a U. S. battleship, the Maine, was the torch that ignited the flames or war, which… Read more »

We as a planet should realize that we can’t put our future in the hands of psychopaths. There needs to be an empathy test to weed out the planets destroyers before they are allowed to lead.

We do not have enough time to have leaders that look after themselves or their political parties above and beyond the planet.

“Although it claimed to work openly, the CPI created front organizations and secretly subsidized newspapers overseas.”

– As did the CIA from the 1950s on. And today, much of Hollywood is subsidized by the Pentagon to push its propaganda line.