Deep thoughts: How moving ICBMs far underground will make the whole world safer

By Ivan Oelrich | April 28, 2021

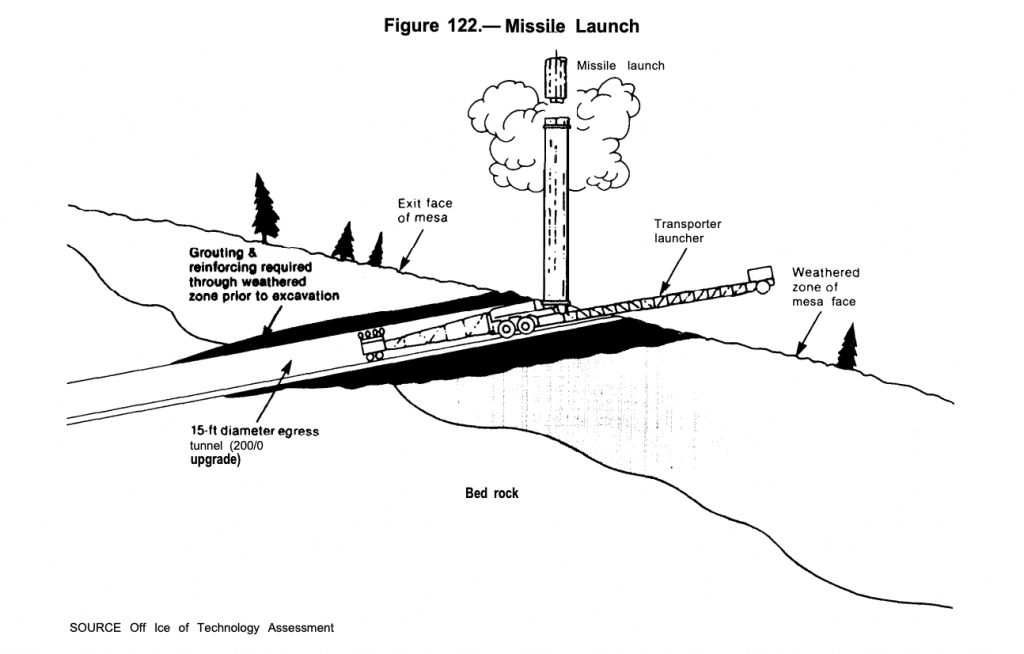

A depiction of part of a deep underground missile basing system from a report, "MX Missile Basing," issued in 1981 by the US Office of Technology Assessment.

A depiction of part of a deep underground missile basing system from a report, "MX Missile Basing," issued in 1981 by the US Office of Technology Assessment.

The long-range, or strategic, nuclear weapons that make up the core of America’s nuclear arsenal are all inherited from the Cold War. Although the weapons are not in quite as much of an aging crisis as it is sometimes portrayed, they are indeed getting old and will eventually need to be retired and, most assume, replaced. The US “triad” of bombers, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) owes its origins as much to rivalry between the Air Force and Navy as to careful military planning, but the triad is a structure that became sacrosanct during the Cold War. Now that the nuclear world has been turned on its head since the end of the Cold War, current plans are to simply replace the old triad with a new one.

A cynic might be forgiven for imagining that the future direction of the nuclear arsenal depends more on momentum than careful analysis. Obviously, this is not to say that US thinking about nuclear weapons has not changed at all since the Cold War, only that the dramatic changes in the political and military environment seem not to be reflected by equally dynamic changes in thinking about the future of the triad. There may be multiple explanations for this dampened response.

One explanation could be that nuclear weapons are flexible and can be applied to new uses. Even so, if Russia and the United States woke up tomorrow with no nuclear weapons, it is unlikely they would immediately start to rebuild the Cold War-inspired arsenals that they have today. Yet, with the end of the Cold War, the US was, in fact, left with this powerful tool, and it is tempting to look for ways to exploit a tool that is at hand. Some scholars argue, for example, that having a robust nuclear capability constantly benefits the United States by swaying non-nuclear contests in favor of the Americans, although I believe all of these arguments fail to account for the costs of making or implying threats.

Another possible cause of the dampening of a revolutionary rethinking of nuclear weapons is that nuclear weapons create their own reality, one that is difficult to escape. The number of nuclear weapons in the world has been going down for decades. The overwhelming bulk of nuclear weapons have always been held by the United States and the Soviet Union—and then Russia—and reductions between them far outweigh small increases elsewhere. These reductions are a result of arms control negotiations, an overall reduction in US-Russian nuclear tensions compared to the Cold War, along with the lower stakes in play between the two nuclear superpowers and the reduced salience of nuclear weapons as high-performance non-nuclear precision-guided bombs and missiles take over many of the tasks previously assigned to nuclear weapons. Even after these reductions, however, the two nuclear superpowers still maintain staggeringly destructive arsenals. That these arsenals are largely legacies of the Cold War is not so important today as the simple fact that they exist.

The US nuclear triad was developed at a time when the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies were locked in a contest with NATO and the West for the future of the world. While most thought that overall the West had the upper hand in that struggle, for decades that advantage was uncertain and nuclear weapons were deemed essential weapons of last resort. Today, NATO has more than six times the population of Russia, 23 times the gross domestic product, over three times as many men and women under arms, and almost 17 times the military spending. Russia knows that it would lose any long war with NATO. Now is it Russia that feels that perhaps it needs a nuclear insurance policy.

Whatever the Russian motivation for its nuclear arsenal, it is far and away the major, perhaps the only, existential military threat facing the United States. This fact has to be dealt with, Cold War or not, and regardless of the state of day-to-day relations between Russia and the United States. To counter this threat, the United States maintains a robust nuclear force that seems tailored to reducing the Russian threat by maintaining a robust counterforce capability.

Rethinking the triad, and the case against SLBMs. Looking at the ever-declining number of nuclear weapons and the inefficiency of spreading smaller numbers of weapons among three basing systems, some more venturesome military thinkers, including a former Secretary of Defense, have suggested that it is time to abandon the triad of nuclear forces by eliminating entirely one of its legs, that is, moving to a “dyad.” Virtually every such proposal specifically recommends getting rid of the land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and relying only on bombers and submarine-based missiles. The strongest argument against ICBMs is that they undermine nuclear stability because they are vulnerable to surprise attack. Because of this vulnerability, they are kept on high alert, ready to launch at all times before incoming enemy missiles can arrive and destroy the ICBMs in their silos, thus creating a “use-it-or-lose-it” conundrum if an enemy attack were detected. Under some circumstance, such as a false alarm, this vulnerability and the high-alert needed to compensate for it could lead to a completely avoidable cataclysm.

It probably is time to get rid of the great majority of silo-based ICBMs, but it would be a mistake to conflate ICBMs with the silos that house them. There are other basing options that have advantages compared both to the current land-based silos and to submarine-based missiles. Keeping land-based missiles in underground tunnels—where they would be essentially invulnerable to attack and therefore need not be kept on high-alert status—is a realistic option that has not received sufficient attention. Moving to such a basing system could open dramatic possibilities for an arms control grand bargain, in which the United States gives up its theoretical first-strike capability, and Russia greatly reduces its nuclear arsenal.

It is fair to ask what benefits ICBMs offered that have made them seem an essential part of the triad up until now, so we would know what the US would lose by giving them up. One advantage is cost. The missiles are expensive, but once in their concrete silos the costs to maintain them and support their crews, even in a high state of alert, is less than the comparable operating cost of either bombers or submarines. In additions, the ICBMs and bombers together presented the Soviets/Russians with an attack coordination problem that made it impossible to destroy both on the ground through surprise. And finally, being land-based, ICBMs offered more secure and reliable communication links than either airborne or seaborne forces.

In contrast, SLBMs get the nod because, being carried on submarines, they are thought to be invulnerable while at sea and most analysts believe that they will remain so for the foreseeable future. Survivability is certainly a big plus for SLBMs, but there is far more to consider before putting the bulk of US nuclear forces on submarines.

The stability of the nuclear balance between the US and the Soviet Union, and later, Russia, has been a central theme in debates about nuclear weapons even if these concerns had limited effect on actual procurement and deployment decisions. In principle, stability is simple. If both sides are in the position where a first strike is difficult and uncertain, and the other side is expected to have enough nuclear weapons that survive a first strike to respond effectively, then there will never be enough of an advantage to going first to warrant starting a nuclear war. Both sides will wait for the other to make the first move, and thus neither side will go first, and the war never starts.

When submarine-based missiles were first introduced, they seemed to be the perfect stabilizing weapons. The first US SLBM, the Polaris, was carried on a nuclear-powered submarine that the Soviets could not find and thus could not attack with or without surprise so the Soviets would never be tempted to try a first strike. The Polaris missiles had a short range, a modest payload, and poor accuracy, making them on all counts terrible weapons to use in a surprise first strike against Soviet land-based missiles. Even with their limitations, however, if the Soviets had attacked, these undersea missiles could have reliably inflicted devastating damage on Soviet cities and industry, deterring any attack in the first place.

Today’s US SLBMs have inherited much of the cachet they earned during their early use in the Cold War, although they are now entirely different weapons. The submarines carrying the missiles remain undetectable, but the missiles themselves have far greater ranges. This means that the submarines have a wide choice of launch points and can exploit weaknesses in Russian early warning radar systems and can cover all of Russia’s territory. The payloads are much larger, and nuclear weapons are now much more advanced, so the warheads of an SLBM can have explosive yield of equivalent to hundreds of kilotons of TNT. Advances in guidance mean these powerful warheads are extremely accurate. Finally, SLBMs can fly so-called “depressed” trajectories, just above the atmosphere, dramatically reducing their flight times and any Russian warning time. Maneuverable warheads can further increase accuracy and defeat Russian defenses. There is at least one unofficial report of a US submarine-launched missile having been tested with a combination of depressed trajectory and maneuverable warhead.

All of this together means that today’s US SLBMs provide the ideal foundation for a disarming first strike against Russia, able to attack their mobile missiles while still in their garrisons, decapitate command centers, catch bombers on the ground, and take out defense radars. The United States sustains a particularly bad understanding how threatening its nuclear weapons appear to other nations, specifically Russia. One reason for this is the constant use of euphemism. Discussion in the United States, even among those arguing against nuclear weapons, generally refers to nuclear weapons as the “deterrent” force. The follow-on to the current ICBM is, in fact, officially called the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent. From a Russian perspective, however the US nuclear arsenal looks not at all like a retaliatory force for deterrence but a force finely tuned specifically for a disarming first strike against Russia’s central nuclear systems. (Some US analysts, accepting this, assert that convincing the Russians they will lose a nuclear war is, indeed, a very good deterrent.) SLBMs are a key part of that capability.

That is not the end of the problems with SLBMs. Always the first advantage of SLBMs to be cited is their invulnerability. Yet submarines are not tough targets; they are invulnerable because they remain invisible in the vastness of the ocean. In port, submarines are extremely vulnerable. The incentive to strike first in a nuclear war does not come because striking first presents a good outcome and responding second is terrible. It will almost always be the case that going first is a terrible outcome, but it could be appreciably less terrible than being second. Thus, a terrible outcome could still be an incentive to strike first. And being able to destroy a sizable proportion of the US nuclear strike force when it is in port and vulnerable contributes to that incentive. As a result, the submarine force must always operate at a high tempo to keep as many ships at sea as possible, both during times of calm and times of crisis because the last thing the United States would want it to present Russia with a lucrative target during a crisis that is about to disappear, creating a now-or-never choice about a first strike. This high-tempo requirement also makes the submarine missile fleet expensive year-in, year-out.

Moreover, nothing reveals a submarine’s position more quickly than having a ballistic missile break the surface of the water. An enemy can be certain that, at least at that moment, there is a submarine under that point. A counter-barrage with a wide spread of nuclear weapons could have some chance of destroying the launching submarine. It is not clear that Russia will have the ability to detect the point of a launch or that it could instantly launch nuclear-armed missiles against the target area, but the very possibility might limit the ability of US submarines to launch partial loads. If launching does reveal their positions and make them vulnerable, then each submarine could be forced into an all-or-nothing attack.

A further disadvantage of SLBMs is their long-term effect on achieving future arms control goals. Many believe that continuing measured, balanced reductions in the number of US and Russian nuclear weapons enhances the security of both nations but particularly that of the United States. The only existential military threats faced by the United States are the nuclear weapons possessed by Russia (and perhaps soon by China). Past experience makes clear that negotiating arms limits is very much the art of the possible, and options are sharply constrained by the existing inventories of weapons that either side has on hand. When making decisions about future nuclear weapons, an important consideration should be how their characteristics will facilitate or hinder future arms limitation efforts. In other words, when the United States builds weapons, it should be concerned about how to get rid of them. By this measure, submarine-launched missiles do not look good. Submarines are “chunky”; the force cannot include a half of a submarine. The United States could, of course, reduce the number of missiles per submarine under an arms control agreement, but the cost of the fleet depends almost entirely on the number of submarines, not the number of missiles, so the cost per missile will climb for an ever-smaller force.

Enhancing stability through de-alerting and survivability. If the United States wants to maintain a nuclear arsenal—a certainty for the near future at least—then SLBMs, even with all their drawbacks, become the weapons of choice if the alternative is even worse. When considering which leg of the triad to ditch, ICBMs always lose out because they are vulnerable sitting in their silos. In part to compensate for this vulnerability, ICBMs are kept at high alert at all times. Although the US Air Force chafes at the term “hair-trigger,” ICBMs are ready to launch within a few minutes of getting an order to fire. Quick launch allows an expedient, but highly dangerous, enhancement to “survivability,” that is, to launch under attack. If the United States detects Russian missiles approaching, specifically aimed at US ICBMs, then the United States can launch its missiles before the Russian missiles arrive, so the Russian missiles might destroy empty silos but not US missiles. This creates a certain doomsday machine automaticity to the US response that might contribute to deterring a Russian attack, but the consequences of a false alarm could be a calamity unprecedented in human history. The combination of the vulnerability and quick-fire capability of ICBMs makes them very destabilizing weapons.

But any missile is pretty fragile; the vulnerability depends on how the missile is based. Fragile SLBMs are invulnerable on submarines at sea not because the missiles or submarines are difficult to destroy but because no one can find the submarines to attack them. ICBMS are vulnerable on land because they are based in silos that can be attacked by accurate, high-yield nuclear warheads. But there is at least one other basing system that deserves another look.

There was a flurry of research and analysis on land basing of missiles when the MX, later named the Peacekeeper, was nearing completion of its development and needed to be deployed. It was an ICBM with 10 independently-targeted, high-yield, accurate warheads. If based in silos, it would be both a lucrative and vulnerable target, and, at the same time, it would be an ideal first strike weapon, a particularly destabilizing combination by the strategic thinking of the time. So there was a search for a more secure basing system. The leading option was, for a while, putting the missiles on trailers that also served as launchers and that could be moved randomly among a number of shelters arranged along an oval road or “racetrack.” All but one of the shelters would be empty but the Soviets would have to attack all of them to be certain of getting the missile that was in there somewhere. As long as there were more shelters than warheads on the missiles, attacking them would remain a losing proposition for any attacker. For a variety of reasons, this plan was abandoned, and in the end the missiles were placed in silos that are now considered the fatal flaw of ICBMs, yet the plan illustrates that there are basing possibilities other than silos.

There have been many suggestions that would take nuclear weapons off alert—that is, make them impossible to launch quickly in a first strike or in response to a warning of attack, a warning that may be mistaken due to human or technical error. Taking weapons off alert forces more time into a launch process, which could result in more deliberate and safer decisions, although of course nothing can force leaders to be sensible. And decision-makers, knowing there is a long de-alerting lag, might feel forced to set the launch process in motion earlier than they would otherwise. Even if only US weapons were off alert, Russia could feel that it also had more time in a crisis and thus would be less likely to grasp for drastic responses. So reductions in US alert levels alone could enhance not only the security of Russia but that of the United States as well. This benefit reflected back on the United States may be important, but the advantage accrues only if Russia can see that US weapons are off alert—and that is where SLBMs are at a disadvantage. The United States could devise some ways to stretch out the launch time of missiles on submarines but, because submarines survive by being invisible, it is difficult to picture de-alerting measures for submarines that Russia could see and trust while still preserving the submarines’ stealth.

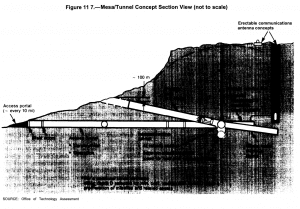

Deep underground basing. Another option considered for ICBMs at the time of the MX deployment was to dig tunnels deep underground, probably by boring more or less horizontally into the side of a mountain or mesa. Then, even if the Soviets (or, today, Russians) knew where the missiles were buried, they could not destroy the missiles under a kilometer of rock even with powerful nuclear bombs. Entry and exit points would be detected during construction or later with overhead satellites and those could be bombed and destroyed. Thus, a necessary part of the scheme was to bury the missiles along with their boring machines. After a nuclear attack, the boring machines could be aimed toward any of a range of exit points and start drilling away. The Russians would not know where to attack, because even the crews inside the mountain would not have decided on an exit point before they started digging out. If one loved acronyms but hated the idea, then the proposal was called Deep Underground Missile Basing.

The United States has built many different types of submarines, and, while they are fabulously expensive, the country does have experience with their design, construction, and operation. The United States has never used underground missile basing, so the technical challenges have never been worked out in detail. But it is probably true that digging a hole into rock, even a deep one, is technically easier and cheaper than building a nuclear submarine. Maintaining and operating a tunnel in rock is definitely cheaper than maintaining and operating a nuclear submarine

Potential technical challenges were not, however, the primary constraint that doomed consideration of underground basing. The key, insurmountable shortcoming to the basing scheme was that the missiles could not be launched rapidly but only after days of digging. The Air Force would have rejected the idea on that criterion alone, whatever other technical merits or drawbacks, because the United States has always maintained a war-fighting strategy that allows at least the possibility of a first strike against the Soviet Union/Russia to reduce damage from a possible attack from them, and that requires ready-to-fire missiles.

Yet today, with hopes of much-reduced reliance on nuclear weapons, the inability to launch quickly may be the principal asset of underground basing. When making decisions about future nuclear weapons, a useful design criterion would be to build weapons such that it is physically impossible to do anything stupid quickly, and that could be accomplished by taking most nuclear weapons off alert. With submarines or missiles in silos, there may be some added stability with de-alerting, but the benefit is limited if the alert reductions are not visible to Russia or they are easily reversed. Russia might still fear a surprise first strike and act rashly as a result. The worst possible case occurs if weapons are vulnerable when going back on alert, presenting Russia with a now-or-never choice about a counter-force attack.

Underground missile basing, on the other hand, makes quick launch physically impossible, and visibly so. Russia could be provided additional assurance that the United States is not planning a surprise attack by putting a seismic monitor near the burial site (manned or unmanned; there are unmanned seismic stations scattered over the world to monitor, for example, possible clandestine underground nuclear tests) that could easily and reliably detect the work of the boring machines and a few times per day send a signal that no digging is taking place. If the United States ever did want to dig out, it could turn off the monitor—but then the lack of signal would be a warning to the Russians. Thus, the Russians could be continually reassured that the weapons were not being prepared for a surprise attack.

What if the United States wants to be able, perhaps only in extreme circumstances, to launch missiles quickly, even, perhaps, in a first strike? For example, while wanting to reassure Russia, the United States may want to maintain the ability to launch a disarming preemptive strike first against, say, North Korea’s nuclear missiles as they are being prepared for launch. This question exposes the near universal logical error in discussions of land-based missiles: the all-or-nothing basing assumption. The United States does not need to decide between putting land-based missiles in vulnerable silos or deep underground. There is no reason not to do both. If the United States needs to have a dozen or so missiles ready to launch on an hour’s notice to deal with an imminent threat from North Korea, those missiles can sit in silos. In limited numbers, these ready-to-launch missiles pose no first strike threat to Russia. To be able to retaliate against a large nuclear-armed country, which today means China or Russia, to deter them from striking in the first place, would take more missiles and nuclear weapons. But those could be safely based deep underground.

The last several years have seen a significant undermining of US-Russia arms control, including the end of formal treaties, norms, and efforts toward further progress. Arms control may seem to be in long-term eclipse, but the situation may also improve dramatically and suddenly, perhaps based on changes in leadership in Russia, the United States, or both. No one should exclude the possibility that arms control will once again be a cornerstone of nuclear planning for both countries.

President Biden’s decision in favor of a five-year extension of the START agreement may bode well for follow-on arms control negotiations. If so, then a criterion for today’s decisions about the next generation of nuclear weapons should be that their design, characteristics, and operations not close off future desirable options for arms control agreements. Submarines have the problem that they cannot be visibly taken off alert, and they are “chunky.” But missiles based deep underground are unambiguously incapable of rapid launch and with normal surveillance, perhaps enhanced with minimally intrusive cooperative monitoring, the number of missiles within an underground base cannot be secretly increased. But the number could be reduced in response to arms control negotiations—by one missile, or by half, or by 90 percent, with little effect on the remainder.

In the longer term, reducing the first strike capabilities of both Russia and the United States opens up dramatic possibilities for an arms control grand bargain. The US nuclear arsenal clearly outclasses Russian’s. Russia has real worries, at least theoretically, of a US disarming first strike. The effectiveness of such a strike remains extremely uncertain, but nuclear planners are always conservative, so Russian planners will assume the worse. They might, for example, assume a US strike is capable of destroying 90 percent of Russia’s long-range weapons. If they decide they need a certain number of surviving weapons—let’s call it N— to reliably deter an attack, that means they require ten times the N weapons to start with. The United States, Russia, and the rest of the world would be far safer if that 90 percent of the Russian arsenal could be reduced through negotiations rather than by blowing it up.

The potential exchange: The United States would give up its first strike capability, and Russia would proportionately reduce vulnerable weapons. Such a fundamental transformation of the nuclear superpower relationship seems utterly impossible for the foreseeable future. But the future is foreseeable for only a few years while experience has shown that the nuclear weapons either side builds are with us for decades. No decision the United States makes today should be allowed to forestall arms control options further in the future. No one should want to block the exit ramps.

The most important point here is that the nuclear triad was fine-tuned to a Cold War nuclear world that is long since gone. It would be an extraordinary, indeed unbelievable, coincidence if the best replacement for the inherited triad of nuclear launch systems was simply an updated version of the Cold War arsenal. The United States should broaden its options for the next generation of weapons. Dropping one leg of the triad is one such option. Keeping land-based missiles in underground tunnels is another. To eliminate the first strike threat from SLBMs, perhaps submarines should be armed only with slower, long-range cruise missiles. The fundamental plea is to recognize that the nuclear world is different and can be made safer. Doing so requires that designs of the next generation of nuclear weapons should begin with clean sheets of paper.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Ground Based Strategic Deterrent, ICBM, MX missile, SLBM, deep underground basing, nuclear triad

Topics: Nuclear Weapons

Ivan Oelrich’s rethinking of the Triad provides genuine food for thought, as does his recalling of OTA’s analysis of MX basing modes. I particularly like his suggestion that the U.S. could construct both a rapid-response group of silo launchers as well as a deep underground base, although this might be thought of as leading to a “Tetrad” rather than the existing Triad. I am, however, leery of the suggestion that boring machines will necessarily function after a nuclear strike as well as they will prior to a first strike. Despite humanity’s long experience digging tunnels, such a scheme would have… Read more »

Are mountains capable of withstanding a nuclear explosion? I was under the impression that a large nuclear warhead would vaporize a mountain.