A VR journey into the nuclear bunker offers chilling lessons on US nuclear policy

By Susan D’Agostino | February 14, 2022

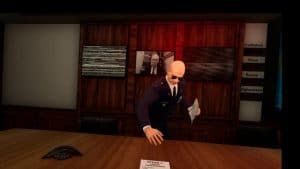

Sharon Weiner and Moritz Kütt try on the VR headsets for The Nuclear Biscuit, a virtual reality experience they created that allows players to wargame a missile attack from the point of view of the US president. Photo used with permission from Sharon Weiner.

Sharon Weiner and Moritz Kütt try on the VR headsets for The Nuclear Biscuit, a virtual reality experience they created that allows players to wargame a missile attack from the point of view of the US president. Photo used with permission from Sharon Weiner.

“Mr. President, we have a national emergency. Please follow the military officer right away,” a voice says as an alarm blares. Evacuated to a secure facility, the president is greeted with a digital clock counting down from 15 minutes. “Mr. President, this is Strategic Command. If you don’t make a decision before the time on that clock hits zero, we will lose our entire ICBM force.” The president is then presented with three recommended attack options, the least of which predicts five million to 15 million casualties. If an immediate decision isn’t made, the voice becomes adamant: “Mr. President, I need your guidance!”

So begins The Nuclear Biscuit, a virtual reality (VR) experience that allows players to wargame a missile attack from the point of view of the US president. This research tool, which also serves as an educational game, is named for the actual nuclear biscuit—a card containing nuclear launch codes that the president is supposed to carry at all times. That card offers the US president sole authority over more than 40 percent of the world’s nuclear warheads. Such power has the potential to trigger a civilization-ending nuclear attack.

The simulation is the brainchild of Sharon Weiner of American University and Moritz Kütt of the Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg. The research duo recruited students at Princeton University (where Weiner and Kütt met and conceived the project) and Washington DC-based policy professionals for their study, which seeks to better understand decision making amidst the pressure and uncertainty of a nuclear crisis. Over the past two years, world leaders, policymakers, and citizens in the United States and Europe have also had the opportunity to try the simulation.

“I was virtually paralyzed by the end,” Robert Meyers, a citizen who experienced the VR experience at the February 2020 Munich Security Conference, said. “The experience was so real that it was chilling.” Two years later, Meyers continues to second-guess the choice he made in the simulation. “I didn’t ask the questions that I should have.”

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists caught up with The Nuclear Biscuit’s co-creators to talk about technical challenges involved in producing their nuclear-themed VR, Easter eggs they embedded in the simulation, and the ways in which players surprised them. What follows is an edited and condensed transcript of that conversation.

What motivated this work?

Sharon Weiner: In my first VR experience, I was a bunny running from aliens. I was immersed in the experience. I immediately thought about foreign policy decision making and about how people make irrational choices and use shortcuts in a crisis situation. I thought that if we could immerse people in a virtual situation to practice [nuclear] deterrence, we’d start to understand the degree to which they conform to the expectations of deterrence, which assumes rational decision making. That became an idea about using VR for this purpose. I didn’t know anything about VR, but Moritz knew a whole lot. Plus, he’s that rare combination of political scientist and physicist. So, we started a conversation.

Moritz Kütt: I’d been working on using technical means to help nonproliferation arms control and disarmament. This can be verification technology but also virtual reality technology. I’m interested in understanding how new technology can help solve this problem. For The Nuclear Biscuit, the first thing we did was download an Oval Office demo so we could walk around in the Oval Office in VR, which in itself is pretty amazing.

Many people associate VR with play. Is there any risk with people thinking nuclear decision making is a game?

Sharon Weiner: When we use this for generating experimental data, we exclude people with significant VR experience, not just because they might think it’s a game, but because it’s unclear how immersed they are.

Games are about storytelling, right? In our case, the story was provided by US decisions about structuring nuclear strategy. In putting that story into the virtual experience, we tried to be true to the options that story presents or precludes.

The goal is to get [participants] to engage with the story as it exists, given [nuclear] strategy and force structure. We want them to come to their own conclusions about their willingness to accept the assumptions of deterrence.

We’ve not yet analyzed the data from our experiments, but I think it’s fair to say most people came away skeptical [about US nuclear strategy]. They wanted to know whether [the particular game they played] was a nuclear accident or a real attack. The answer is, “it’s both, and it’s neither.” Most people find that answer really unsatisfying.

Is there a correct action or set of actions for players in the scenario you’ve created?

Sharon Weiner: The right thing depends upon the values that a person brings to the experience. If you are US Strategic Command, the right thing is probably using your intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) before they’re destroyed. If you are Eamon Javers with CNBC, the right thing is protecting people and not acting immorally.

But one person gets to make that decision. And in reality, that one person gets 15 minutes or less to decide which of those values they want to maximize.

How do you decide how to end something when you can never resolve the issues in the time you have? The president only knows if the attack was real once the weapons land.

Moritz Kütt: That’s true for the real case as well. The president in a bunker never sees anything. The president doesn’t have a window. The president only relies on information given by third parties and technology. We know of many incidents from the past where this has failed already. We leave this open because the president would never really know for sure.

Did your nuclear theme present unique technical challenges?

Moritz Kütt: We tried to come up with new ideas to make the experience more immersive. In some of the videos, a virtual chair is replicated in the physical world. People can walk up to the chair, grab it, and then see it moving in VR. That is usually the moment people say, “Yeah, this is something serious.” Then they sit down at the Resolute desk in the Oval Office.

Sharon Weiner: The development of VR technology isn’t at the point yet where some AI listens to the decisions you’re making and calls up one of several hundred responses. But, Holosphere, the company we worked with for the VR part of the project, developed a unique mechanism. We listen to what the person says, and we have a tablet of responses. We trained each other to come up with similar responses to similar [scenarios] as dictated by nuclear strategy.

When participants take part in the simulation, what do they look like from the outside?

Moritz Kütt: In the beginning, people sometimes give the impression that they still know they’re in a hotel conference room or the basement of Princeton University. But as soon as the alarm starts and they sit down to make decisions, people seem to really think, “Now it’s a crisis. We have to make a decision.”

People start tapping fingers on the table, or they move one foot. They repeat what’s said to them, like numbers or important details of the brief.

Sharon Weiner: There’s an option in which the Secret Service tries to evacuate them. Some people get up to try and leave. A general then says, “Wait, please give me guidance for what to do.” People will have animated arguments with this general, who of course doesn’t exist. They say, “No, I’ve decided to go!” They gesture wildly and sometimes swear.

This is anecdotal, but [the people who try to leave] seem to be people who are less inclined to launch. As soon as they get up, the military officer says, “We’re anticipating you being out of contact. Can you at least give us some guidance for how to behave until we can talk to you again?”

People say, “No, I’m not going to do that! Why should I do that!?” We’ve had people bang the table. People fidget and engage in repetitive motions. Afterward, they don’t remember what they did.

Have you been participants, or do you know too much to be fooled?

Sharon Weiner: We built it from the ground up, so we know every conceivable part of it, including the Easter eggs embedded in it that few would notice but are there just for fun.

Easter eggs?

Moritz Kütt: Bruce Blair, a former Air Force officer, who was also a missileer helped us with the script. He unfortunately passed away last year, but if you turn right in the [simulated] Oval Office, you can see him.

Sharon Weiner: Also, at the end of a newscast [in the simulation], we threw in the names of people, like a high school student who helped [on the project].

In the experience, the player—the simulated president—is presented with three options: low-, medium-, and high-level retaliatory responses. Is one of these options more popular than the others?

Sharon Weiner: There are actually an infinite number of options. Participants are told repeatedly and at specific times that the military wants to help them build their own option. We haven’t yet analyzed the data, but based on general observations, most people never build their own option. Most people do launch. There seems to be a general tendency towards [the low- or medium-level retaliatory] options. Very few people decide not to launch. Is that fair Moritz?

Moritz Kütt: Yes. The difficult part is that, initially, this experiment was only a research project [with the goal of publishing] an academic paper. But, very quickly, it turned out to be an educational tool—something to show people without any research questions. By now, about half of our participants are policymakers.

It’s kind of unfair for us to talk too much about what they’ve done. But we also shouldn’t wait to use this as an educational tool, because the longer we wait, the more dangerous [the world] gets.

You’ve offered the simulation in the United States and Europe. What differences have you observed in these two settings?

Moritz Kütt: People outside of the US appear to be less immersed, perhaps because they know they could never become US president. As soon as you start thinking, “I couldn’t be in this position,” you are not mentally in the position.

Europeans appear to ask questions about whether the British, the French, or the Germans have seen the attack, and they ask what they’re doing. Until the end of the 15 minutes, we tell them that we’re trying to get [allied countries] on the phone but that it’s very hard to reach them.

Is there anything that surprised you in this research?

Sharon Weiner: Many assume that missile defense will save them from an incoming Russian ICBM attack. When they’re told that the missile defense system provides little to no protection, they don’t believe it. So many insisted that we had to add another person saying the same thing. That surprised me. I thought people close to nuclear policy would be aware that the missile defense system is not going to help.

Moritz Kütt: I was surprised that, so far, no one has ever asked for their family. We recorded answers [for questions related to family]. Sharon is one of the voices. But it doesn’t occur to people in this situation to ask, “Where are my kids?” or “Where’s my partner?”

Sharon Weiner: After the experience is over, the presidential emergency operations center goes away and we put on the screen, “Thanks for participating, the experience is over.” I was surprised that people would still be immersed in the experience.

Originally, I had to tap people on the shoulder to tell them the experience was over. But this scared the bejesus out of them because they were still immersed in the experience. So, we tried to make it more obvious that the experience was over. We go up to them and say, “THE EXPERIENCE IS OVER NOW! WE’RE GOING TO TAKE OFF THE HEADSET!” But even when we cut off everything and tell them, they’re still in it.

After someone participates, they always want to talk about what they’ve just gone through. We are the first people they see so we let them lead the conversation.

What’s next after this?

Moritz Kütt: First, we want to rest from being confined in basements playing nuclear wars all the time! This is not some something that is necessarily pleasant. But then we want to analyze the data.

In the long run, we would ideally make this available to a wider audience, but we don’t know yet how, when, and where this would work out. People ask if they can download this on Steam, which is a common platform for computer games. We say “no” because so far, it’s just a research tool.

Sharon Weiner: We’ve been discussing how to make this available as an educational tool for teachers that want to talk about these issues. Students’ nuclear strategy literacy, at least in the US, is quite poor. In a perfect world, we’d reach out to all of them. But there are equity issues. Not every high school can give a virtual reality headset to every student. What are the tradeoffs between trying to make this experience accessible to more people? We’re having those conversations.

[In our simulation,] we controlled for the pressure of time. There are other variations we’d like to control. Given current events, I’d really love to have two people—one is Russia, and one is the US—test the notion of “escalate to deescalate.” How quickly would the situation escalate?

The former head of Strategic Command has said that every time they play these war games, they always end in thermonuclear war. But the presumption about “escalate to deescalate” is that the US can control the use of low-yield nuclear weapons in an otherwise conventional conflict. We actually have a means to test how realistic that assumption is. I would love to do that.

What do you want players to take away from the experience?

Moritz Kütt: We want them to learn about how nuclear deterrence plays out. We’re grateful that people showed up in large numbers for the experiment. We also wanted to educate people on current US nuclear strategy, its potential consequences, and the size of the decision the single person in this room—the US president—would have to make and the circumstances in which this would occur.

Sharon Weiner: These are choices that [US policymakers] made about nuclear strategy infrastructure, but they’re choices. It invites people to say, “I just experienced the choices we’ve made. Think about other choices we could make instead.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.