As tensions mount on Ukraine’s borders, it’s time to understand what led to the INF Treaty’s demise

By Aaron J. Berliner, Jake Hecla, Michael Bondin, Austin Mullen, Elena Osorio Camacena, Alex Droster, Dinara Ermakova, Tyler Scott Nagel, Nicole L. Nappi, Katherine J. Oosterbaan, Sarah R. Stevenson, Chelsea D. Willett, Eric F. Matthews, Manseok Lee, Karl van Bibber, Michael Nacht | February 16, 2022

Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile system with two 9M723K5 missiles, at a Russian demonstration of military technology in 2017. The Iskander system is reported to be capable of firing ballistic missiles that can carry a tactical nuclear warhead. Photo by Vitaly Kuzmin

Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile system with two 9M723K5 missiles, at a Russian demonstration of military technology in 2017. The Iskander system is reported to be capable of firing ballistic missiles that can carry a tactical nuclear warhead. Photo by Vitaly Kuzmin

The escalating hostilities between the Russian Federation and Ukraine have forced many analysts to reconsider the future of the European security environment. Europe’s threat landscape has changed dramatically in the last decade. Arms control has crumbled, while an increasingly aggressive Russia has developed sizeable territorial ambitions and a prodigious appetite for risk.

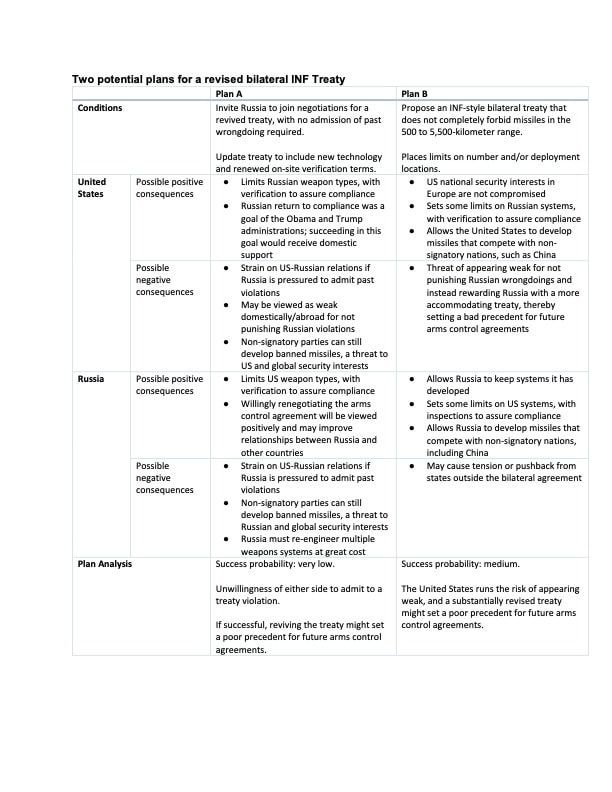

These developments have resurrected nightmares of nuclear warfighting long considered a relic of the Cold War. Among the most daunting developments in any future effort to rebuild the shattered regional security environment is the demise of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which prohibited a class of weapons considered to be highly destabilizing. Now shorn of all but the most basic arms control treaties, the continent is dotted with an unprecedented array of precision missiles while confrontation looms in the east.

In February, open-source images of the Russian buildup confirmed mobilizations of short-range Iskander missiles, placement of 9M729 ground-launched cruise missiles in Kaliningrad, and movements of Khinzal air-launched cruise missiles to the Ukrainian border. Collectively, these missiles are capable of striking deep into Europe and threatening the capitals of a number of NATO member states. Russia’s missile systems are not necessarily intended for use against Ukraine, but rather to counter any NATO efforts at intervention in Russia’s imagined “near-abroad.” As tensions mount at the borders of Ukraine, it is critical to understand the events that led to the demise of the INF Treaty, and the challenges that may face efforts to reimpose limitations on intermediate-range forces.

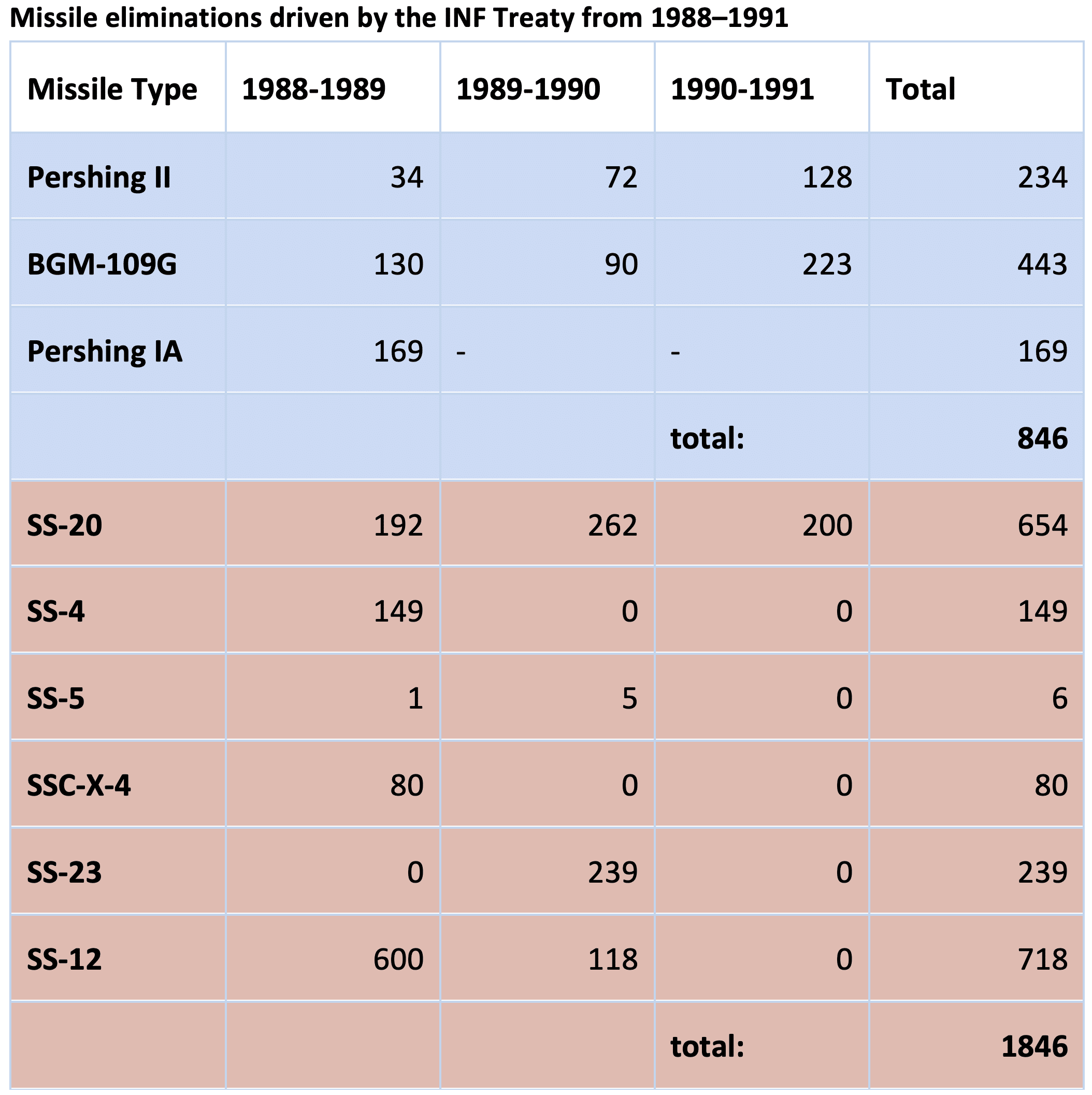

The demise of the treaty has already led to changes in US and Russian nuclear and conventional forces. In the wake of the treaty’s demise, the deployment of intermediate-range missiles in Russia and the United States is unavoidable, given the security environment each nation faces and the lack of political will toward arms control. Complete re-institution of the treaty terms is likely unrealistic, and future arms control treaties must therefore consider the existence of these previously banned technologies. We see two possible options for an agreement to replace the INF Treaty: an ideal Plan A or a more pragmatic, but limited, Plan B.

The demise of a treaty. On February 1, 2019, the State Department officially declared that the United States would withdraw from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, claiming Russia had violated the treaty’s range limits with missile tests beginning in 2007. Russian President Vladimir Putin responded in kind by announcing plans to withdraw from the INF. Putin accused the United States of violations and promised the prompt development of weapons of previously proscribed range. A few weeks later, US Defense Department officials test-launched missiles forbidden by the treaty, which bans all ground-launched missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers in signatory states.

China, Iran, and North Korea—all non-signatory states to the INF Treaty—are making efforts to acquire intermediate-range missiles. Moscow has already expressed concerns about these ambitions, and support for the expansion of the INF Treaty to include more states. Reports in 2018 claimed that China’s intermediate-range ballistic missiles constituted “approximately 95 percent” of the People’s Liberation Army missile force. As China’s nuclear stockpile continues to grow, the restoration of a bilateral INF Treaty may no longer be in the national security interests of both the United States and Russia. The United States has expressed concern that the INF Treaty jeopardizes its ability and readiness to counter the missile threat from China and other actors, while the Russian Federation has, as the Arms Control Association puts it, contended that the treaty “unfairly prevents it from possessing weapons that its neighbors, such as China, are developing and fielding.”

Impacts on US forces. The United States laid out its responses to Russia’s violations of the INF Treaty, and considered the implications of withdrawing from the treaty, in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review. The report highlighted three key areas of force development: the deployment of the W76-2 low-yield, submarine-launched ballistic missile warhead; the development of a modern nuclear-armed, sea-launched cruise missile; and research into a ground-launched, intermediate-range, nuclear-armed cruise missile. Of these, only the ground-based cruise missile would have been addressed by the treaty, which did not cover sea-launched systems. However, some of the new developments in all three systems can be interpreted as a response to the post-INF security and political environment.

The manufacturing of low-yield warheads for the existing US submarine-launched ballistic missile fleet is a response to the perception that Russia has a greater number and variety of low-yield weapons intended primarily for theater use. Decision makers see these systems as a credible nonstrategic option that could be used to counter so-called “escalate to de-escalate” strategies. A low-yield submarine-launched ballistic missile has been claimed to help close this “gap” in US extended deterrence. Without an INF-like treaty, a further increase in these systems could be possible.

A nuclear-armed, submarine-launched cruise missile provides much the same effect as its low-yield ballistic missile counterpart but remains a longer-term goal due to the requirement for a new airframe. The United States retired its previous nuclear cruise missile fleet, a variant of the Tomahawk cruise missile, in 2010. The development, manufacturing, and deployment of a new fleet will take eight to 10 years, whereas disabling or removing the thermonuclear secondary from the W76-1 is a relatively simple process. A new cruise missile has major implications in East Asia, where China’s Anti-Access Area Denial tactics and non-strategic nuclear arsenal threaten US interests. China uses its own ground-launched cruise missiles and ballistic missiles to target US naval bases and fleets in the Pacific. As with US deterrence against Russian non-strategic weapons, deterrence against Chinese low-level nuclear use may not be credible unless the United States has non-strategic forces of its own.

US development of a new ground-launched, INF-class cruise missile has less obvious military applications. Unlike sea-based missiles, an intermediate-range, ground-based system must be based in areas near potential adversaries. This raises difficulties for deploying this capability in Europe and especially in Asia, where many potential defense partners have refused to host nuclear missiles. The United States has historically deployed nuclear weapons in Europe as a counter to Russia, but future deployments would likely be very contentious, catalyzing new anti-nuclear and anti-NATO activity. Possible locations include Poland and Romania, where the United States currently bases an anti-ballistic missile defense system. However, Moscow has already voiced multiple concerns over the possibility of using missile defense sites to base offensive warheads, and would see this as a very aggressive move by the United States.

With the end of the INF Treaty, the United States has begun to manufacture parts needed to assemble and test a ground-launched cruise missile, thus signaling its intent to move forward with post-INF ground forces. The government has also maintained that, if Russia is willing to return to arms-control negotiations or abide by the terms of the INF Treaty, the United States is willing to negotiate a halt to intermediate-range missile development and deployment. It is thus likely that this missile development program is a political tool more than a vital component of the US arsenal.

Impacts on Russian forces. The Russian Federation has not supplied an exact accounting of its response to the termination of the INF Treaty. Given the Russian government’s demonstrated willingness to use force to coerce states in its “near-abroad,” such as Georgia and Ukraine, it is possible that the Russian Ministry of Defense seeks to increase its capability to credibly threaten neighboring states with nuclear-armed ballistic and cruise missile platforms. An improved intermediate-range missile capability would be a credible threat against these states.

The Russian military faces a very different threat landscape than it did in the 1960s, when development began on Russia’s intermediate-range forces. The missile that ultimately triggered INF negotiations, the SS-20 intermediate-range ballistic missile, was created as a way to hold conventional troops at risk in a potential European-theater conflict. Today, the notion of the Russian Army sending armor through the Fulda gap is far-fetched. However, Russia has nonetheless developed systems that reprise the roles of pre-INF systems designed to respond to large-scale war in Europe.

It is unlikely Russia is considering a return to Cold War-era plans of fighting a nuclear war to the Rhine. Instead, it is likely that new intermediate-range systems would be used to threaten states in the near-abroad and to restrain NATO if it is considering intervention. Because intermediate-range systems are distinct from intercontinental-range systems intended to target the main adversary, there may be a perception that the threshold for use is lower. This may aid in pressuring those in the near-abroad to accept Russian demands when involved in a high-level conflict.

US concerns about Russian violations of the INF Treaty focus on the Novator 9M729, which the United States claims is an upgrade of the existing, INF-compliant 9M728 cruise missile. Russia has presented its development of the 9M729 missile as an effort to modernize its missile arsenal, essentially upgrading the stalwart 9M728 by fitting it with a higher-yield warhead and an improved guidance system. Russia claims the 9M729 missile has a reduced range from its predecessor, due to the increased weight of the new components.

US open-source missile experts likewise strongly contest Russian claims of INF Treaty range compliance. The US Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center has estimated the 9M729 missile’s maximum range at 2,500 kilometers. Russia’s counter-claim that a missile small enough to fit in the 9M728 canister could not reach such range is without merit, as the size of the canister is comparable to that of the RK-55, which was discontinued in 1987 due to its non-INF-compliant range of 3,000 kilometers.

Secondary concerns revolve around the 9M723/Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile. While legally an INF-compliant system, it has been tested to significantly beyond 500 kilometers after treaty withdrawal. Official statements suggest the missile can be armed with multiple conventional warheads weighing up to 700 kilograms or a single nuclear warhead. In January 2018, crash debris from a 9M723 was photographed in Kazakhstan more than 620 kilometers from the Russian border, which exceeds the INF treaty limit of 500 kilometers. Analysts suggest the range of the missile may exceed 1,000 kilometers in some configurations.

The INF Treaty ended in time. The wreckage of the Iskander launched from the Russian Federation fell on the territory of Kazakhstan outside the missile range, this is +620 km from the border of the Russian Federation. pic.twitter.com/4HrnHl2lvb

— Evgeniy Maksimov (@PararamTadam) January 11, 2020

In terms of its operational role, the 9M723 missile has seen successful battlefield use since being fielded in 2006, and was used in the Russo-Georgian war to kill a Dutch journalist, as the Dutch government later confirmed. The Iskander system seems to loom large in the consciousness of the Russian Ministry of Defense as a primary pillar of both defense and deterrence. In a speech about NATO ballistic missile defense in 2008, then-President Dmitry Medvedev specifically invoked the system by name as a means of responding to deployments in Eastern Europe, a role not well suited to a sub-500-kilometer system.

Placement of the Iskander system began officially in 2010 in the Leningrad Military District. Reports suggest it has also been deployed in Syria, and across the western border of Russia in Kaliningrad. Assuming a conservative range of 750 kilometers, the missile could target a variety of Baltic and European capitals.

The presence of such systems serves as a visible reminder of Russian power. Intermediate-range systems provide a means of striking NATO targets throughout a sizable portion of Western Europe. Due to short warning times, quick deployment timelines, and high survivability, the road-mobile systems being deployed enhance Russian deterrence against European states and may cause leaders of those states to reassess the credibility of US extended deterrence.

While there is little practical difference between threatening European states with an intercontinental ballistic missile or an intermediate-range missile, “short warning time” missile systems can have a large psychological impact on the general public, should Russian propaganda focus on that aspect of these systems. This may cause political pressure to deploy defensive or offensive systems. It is likely that the portion of the European public opposed to US nuclear weapons would respond with political pressure of its own, resulting in increased internal polarization and inter-alliance tension. Such an outcome would fit squarely within Russian interests.

Moving forward. The demise of the INF Treaty is likely an irreversible development. Russia has invested heavily in the Iskander, with 13 launch complexes known as of April 2022. The Iskander’s elimination is nearly unthinkable from a budgetary and capability standpoint. Moreover, China, a proposed third signatory for an “expanded” treaty, has made it clear that it has no interest in giving up its rich variety of intermediate-range missiles.

The fastest and safest path forward for international arms control may be to focus US efforts on pursuing a heavily revised bilateral treaty with Russia, rather than trying to resuscitate the original agreement. A revised INF Treaty would ameliorate the reliance on New START as the only arms control agreement between the two states, and shore up the credibility of US and Russian commitment to nuclear nonproliferation. China and Europe would likely support any efforts to create a new US-Russian bilateral treaty.

The possibility of crafting a new treaty will hinge on the negotiation of mutually acceptable terms regarding new weapons technologies. These terms may focus on deployment regions—for example, creating an intermediate-range weapons-free zone in Europe and European Russia. Such a provision would require minimal investment, would create minimal disruption to existing weapons programs, and would not require the development of intrusive verification measures. Alternatively, a New-START-like agreement could be created to provide for numerical limits and mutual inspections of intermediate-range forces.

A new treaty will also require verification methods to resolve questions relating to compliance. The development of verification measures would require function-related observable differences to be identified on dual-capable platforms. One option is to revive the INF Treaty’s Special Verification Commission. On-site verification was effective at one time and would allow both the United States and Russia to address their concerns, as well as forcing any violators to return to compliance.

Policy options for US leadership. It would be challenging to unequivocally prove past violations without an explicit admission from Russia, the United States, or both. Future bilateral negotiations should incentivize the United States and Russia to come to the table by including, if needed, discussion of the alleged past violations without requiring either party to confirm or deny the allegations. By renegotiating the terms of the treaty in the context of violation allegations, the parties will be able to define more explicitly what does and does not constitute a violation.

We see two possible options moving forward. In Plan A, the United States would invite Russia to the negotiation table for an opportunity to reinstate the INF Treaty under modified terms, taking into account new technology and providing for a mutually agreeable return to verification. Such a plan, given current events, is highly unlikely but should be considered should a dramatic rapprochement take place.

Plan B may provide a more palatable option. If an outright ban on INF-range missiles is unacceptable to one or both parties, as logistical factors almost dictate, an INF-style treaty that instead allows limited numbers of intermediate-range missiles, or places limitations on deployment areas, might bring the parties to the negotiating table.

Allowing limited development of previously forbidden weapons would give both Russia and the United States an opportunity to counter intermediate-range weapons development by states outside a revised bilateral agreement. Mirroring some aspects of New START, which limits the number of deployed weapons and establishes detailed monitoring and verification procedures, might make for efficient negotiation and ratification of a modified INF Treaty. Allowing for a small number of previously banned weapons may lead signing parties to propose a feasible composition of offensive arms, which would provide flexibility in negotiation as well as an opportunity to incorporate new technology into the proposed limits. Given the historical unwillingness of either side to admit to a treaty violation, and national security concerns regarding outside parties with INF-banned missiles, a limited-number/limited-area approach may prove promising.

An ideal plan or a pragmatic one? A new INF-like treaty provides the least overall ambiguity for the future of the global nuclear nonproliferation regime. The limited number/limited area plan probably has the best chance of success, but still may be difficult to bring to fruition, given the current state of the US-Russian relations.

Because most of the issues surrounding the continuation and renewal of nuclear arms control treaties are compliance violation allegations, a return to on-site verification is viewed as the best way to prevent future treaties from meeting this same fate. With fears of noncompliance lessened, the terms of the current INF can be recreated and modified according to modern needs.

We confess to being of two minds concerning Plans A and B. While the rigorous exclusion of missiles within the INF range and strict verification are ideal, Plan B has some compelling advantages: First, we see it as the most realistic path to secure an INF-like treaty. Second, it would begin to rebuild dialog and trust between the United States and Russia. Without a significant degree of trust, even the most hermetic treaty (from a verification standpoint) cannot succeed. Third, the deliberate porosity of Plan B would allow both Russia and the United States to maintain and develop systems responding to intermediate-range assets fielded by China and other non-signatories.

In recent years, Russia and China have developed a closer mutual relationship, as demonstrated by joint naval exercises in the Indian Ocean and the East China and Yellow Seas. A treaty allowing both Russia and the United States to protect their own and international security interests on China’s western border and in its maritime region could help unwind and perhaps even reverse that dynamic.

It may be in the United States’ national security interest to eventually expand a US-Russian treaty to include more countries; China, with its entirely unregulated nuclear arsenal, is a prime candidate. However, due to China’s smaller arsenal size and reliance on intermediate-range missiles for its defense posture, multilateralization of the INF Treaty is simply not feasible in the near future. We support the continued exploration of longer-term strategies for developing a multilateral INF-style treaty that would address the concerns of all parties. But until then, the United States must continue to engage bilaterally with Russia to address intermediate-range arms proliferation.

The extended, original version of this paper (“History of and Aftermath from the Withdrawal of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty”) can be found archived here. The authors thank Kelsey Amundson, Lance Kingsbury, Scott Hart, Vanessa Goss, Nkiruka Menankiti, and Fiona Bock for their help with the initial NE-C285 class report and for the opportunity to learn and participate in nuclear security/policy offered by the joint efforts of the UC Berkeley Department of Nuclear Engineering and the Goldman School of Public Policy. This article is based on work supported by the Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration through the Nuclear Science and Security Consortium under Award Number DE-NA0003180. This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: China, INF Treaty, Ukraine

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, Opinion, Voices of Tomorrow

The authors talk persuasively about the dire strategic and political consequences of intermediate-range nuclear forces in Europe. However, in Plan A they look to outlaw all intermediate-range forces, nuclear or otherwise. This is not necessary. The difference in destructive energy is a factor of order 100,000. Meanwhile, in Plan B they apparently would allow some number of nuclear-armed missiles, failing to eliminate the underlying instability. Why not just outlaw intermediate-range nuclear-armed forces in Europe from Portugal and Ireland to the Urals? See: https://thebulletin.org/2019/06/a-short-and-practical-take-on-the-inf-small-and-focused-is-beautiful/

See: https://thebulletin.org/2019/06/a-short-and-practical-take-on-the-inf-small-and-focused-is-beautiful/

Nuclear explosions are ~100,000x more energetic than conventional ones. Thus nuclear-tipped missiles should not be considered in the same class as ones armed with conventional explosives.