Humanitarian crisis: 1,000,000 Ukrainian refugees so far. Millions more expected to follow.

By Susan D’Agostino | March 2, 2022

Station of Kyiv Metro, converted into a shelter after Russian invasion of Ukraine (2022). Credit: https://kmr.gov.ua/uk/content/volodymyr-bondarenko-zaklykav-kyyan-obyednaty-zusyllya-zadlya-dopomogy-spivgromadyanam. CC BY 4.0.

Station of Kyiv Metro, converted into a shelter after Russian invasion of Ukraine (2022). Credit: https://kmr.gov.ua/uk/content/volodymyr-bondarenko-zaklykav-kyyan-obyednaty-zusyllya-zadlya-dopomogy-spivgromadyanam. CC BY 4.0.

Editor’s note: This is a developing story. The number of Ukrainian refugees was updated at 8:25am on March 3, 2022. For full Bulletin coverage of the Ukraine crisis, click here.

Last Wednesday, before Russia launched an unprovoked war on Ukraine, Anastasiia Nechytailo, who grew up in Eastern Ukraine’s Luhansk oblast and settled in Kyiv, went out to celebrate her birthday with friends. But on Thursday morning, she and her younger sister Polina, a student at Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University who lives with Anastasiia in Kyiv, woke to the sounds of air alarms and an explosion near their house. With no basement, the sisters hid in the bathroom, where Anastasiia saw fear in Polina’s eyes. Polina, she knew, understood the horrors of war from having lived in Luhansk after 2014 when Russia attacked the region. That look of fear, more than the sounds of bombs, convinced Anastasiia to flee.

“I had other plans for this spring,” she told the Bulletin.

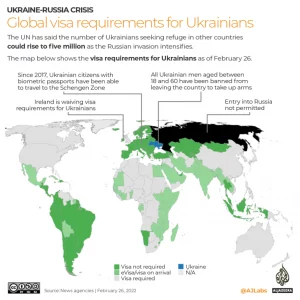

Nearly 1,000,000 Ukrainians—mostly women, children, and the elderly—have fled to neighboring countries and beyond since Russia first invaded Ukraine last week. Men—many of them husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, and boyfriends—between the ages of 18 and 60 have been required by law to stay behind as they may be drafted to fight. The refugees carry bags and children, alongside exhaustion and fear. They travel by foot, train, cars, and busses and queue in cold temperatures at border crossing check points with traffic jams and wait times that are often counted in days.

But this first wave of asylum seekers likely represents only the beginning of this humanitarian crisis. Up to five million people with significant needs may soon be displaced. “Something of this proportion, we haven’t seen that in recent times,” Shabia Mantoo, a UN Refugee Agency spokesperson, said. The current crisis is also inviting an international reckoning on the ways in which countries sometimes privilege some refugees over others.

Many of those who flee travel without knowing where, precisely, they will land. The Nechytailo sisters drove with a female friend to Western Ukraine on a journey that should have taken eight hours but required 34. The women traveled west without stopping to rest; gasoline and food were nearly impossible to find.

“It was a long and terrible road,” Nechytailo said. “At this terrible time, we don’t know which day of the week, but we know what day of war.”

As the trio sought a safe haven, they also worked to make sense of their new reality. “The war took away the opportunity to see my parents, my place of work, my beloved Kyiv, which has become a second home, the opportunity to sleep peacefully and live fully,” Nechytailo said. “Our lovely cities are being destroyed by ballistic missiles.”

Citizens who are displaced from war zones “need safety and protection, first and foremost, but also shelter, food, hygiene, and other support; and they need it urgently,” Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), told his council this week. The number of Ukrainian refugees, he noted, is “rising exponentially, hour after hour, literally, since Thursday.”

Martin Griffiths, UNHCR emergency relief coordinator, speaking in the same meeting, explained how repercussions often multiply in an unfolding crisis. Children miss school and are at increased risk of abuse. Women are at greater risk of gender-based violence. The elderly, people with disabilities, those living close to the contact line, and those in the non-government-controlled areas also “continue to require food, shelter, healthcare, water, and sanitation—and protection.”

Though UN humanitarian workers have been at work “around the clock” in and around Ukraine, ongoing fighting, without assurances from the warring sides that workers will be protected, has hampered efforts, Griffiths reports.

“It’s so critical that the borders remain open, so that humanitarian agencies like UNHCR can reach those in need and provide the basic supplies to help people as they flee,” Joung-ah Ghedini-Williams, UNHCR head of global communications, said.

The European Union is preparing to activate a mechanism known as the “temporary protection directive” that would allow Ukrainian refugees the right to stay and work in its member countries for up to three years. The tool was developed in 2001 after the Yugoslav wars but has not previously been implemented—not during last summer’s chaotic refugee crisis in Afghanistan, not when two million people, mostly Syrians fleeing civil war, sought asylum in 2015 and 2016, and not for any other humanitarian crises in which Europe might have offered swift help.

Disparities in how Western countries treat refugees from different regions, cultures, and religions are troubling. Refugees fleeing war are not undocumented migrants. Rather, they are humans like Nechytailo and her companions who have no choice but to flee. Still, not all refugees are treated equally.

Black and Indian students studying in Ukraine have reported that they have been pushed back from trains and border crossings. “They were shouting ‘go back.’ It was crazy,” Naana Mensah, a student from Ghana studying in Ukraine, told the Globe and Mail. Many African students studying in Ukraine have been stranded. The National Union of Ghana Students, for example, has expressed concern to their government about the “lack of clear plans, directives, and advisory notes” to ensure their safety.

Nearly half of Ukrainan refugees so far have fled to Poland. The country is to be commended for opening its borders and offering shelter to Ukrainians without requiring travel documents or a negative COVID-19 test. But last year, when migrants from Belarus attempted to cross the Polish border, the country erected a barbed-wire border fence to block them.

“We’re letting everyone in,” Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban said in response to the current wave of Ukrainian refugees. Previously, Orban called Muslim immigrants “invaders.” And his party has indirectly claimed that an “‘ethnically’ homogenous country is better than the multicultural West.”

“These people are intelligent; they are educated people,” Bulgarian Prime Minister Kiril Petkov told the Associated Press earlier this week about Ukrainians. “This is not the refugee wave we have been used to, people we were not sure about their identity, people with unclear pasts, who could have been even terrorists.” Petkov’s comments were widely condemned on social media.

On Sunday, the United Kingdom announced a new visa policy that was seen by many as “woefully inadequate” for the current crisis. It would have offered free visas only to Ukrainians who are close relatives of British nationals—a group that included “spouses, unmarried partners of at least two years, parents, children under 18, and adult relatives who are also carers,” but not, for example, siblings of British nationals or those without British relatives who also need humanitarian assistance. Following intense criticism, Boris Johnson widened the United Kingdom’s help, if only by a bit, to include adult parents, grandparents, children over 18, and siblings.

When the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan last summer, Austria sought to block Afghan refugees. But now, Austria has assumed a different posture for Ukrainian refugees. “Of course, we will take in refugees,” Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer said in a national television address. “It’s different in Ukraine than in countries like Afghanistan. We’re talking about neighborhood help.”

The Arab and Middle Eastern Journalists Association issued a statement requesting that news organizations not “normaliz[e] tragedy in parts of the world such as the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and Latin America” and noting that such bias “dehumanizes and renders their experience with war as somehow normal and expected.”

Nechytailo, writing from western Ukraine, does not yet know where she and her companions will land. Still, she has a message to share: “This is the war where Ukraine, on behalf of the whole world, is fighting against inequity.”

Editor’s note: For full Bulletin coverage of the Ukraine crisis, click here.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Putin, Russia, Ukraine, humanitarian crisis, nuclear risk, nuclear weapons, refugee, war

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons