Russia’s information war: painful truths vs. comfortable lies

By Cynthia Hooper | March 9, 2022

City utility workers paint over a “No to War” message carved into ice on the frozen Moyka River in St. Petersburg, Russia. Twitter/@EilishHart

City utility workers paint over a “No to War” message carved into ice on the frozen Moyka River in St. Petersburg, Russia. Twitter/@EilishHart

Amid a media crackdown in Russia, demonstrators are taking to the streets to protest the country’s war on Ukraine. Encrypted tweets and surreptitiously shot videos posted to Reddit and Telegram show Russian police out in force to silence dissent, even approaching passersby and demanding to check their phones. In Moscow, a woman was reportedly arrested on her 80th birthday. One Telegram clip captures a pensioner in Kaliningrad shouting at an officer: “I am a survivor of the Leningrad Blockade! My father died at the front [in World War II]!” The officer replies “And now you are supporting the Ukrainian fascists?” only to be drowned out by a crowd, crying “They are not fascists, they are our friends!”

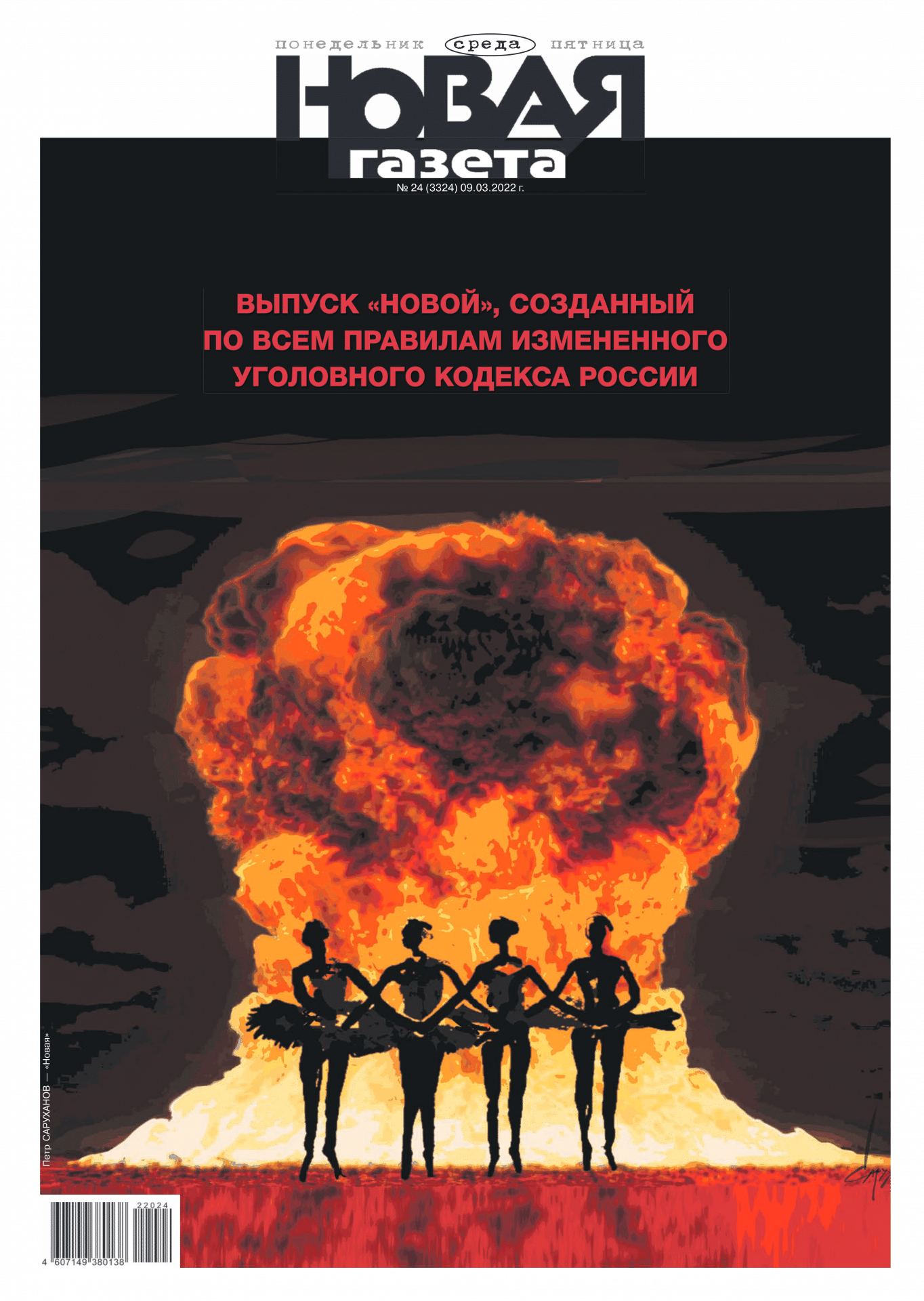

Anticipating that popular unrest could continue to grow as economic sanctions deepen, the Russian government is clamping down on free speech, independent media, and online opportunities for unsupervised, big-group information exchange. Media establishments inside Russia have been shut down for refusing to report only government-approved, highly deceptive versions of events in Ukraine. Western outlets such as the BBC have left the country. Anyone who passes on information that contradicts official sources now faces up to 15 years in jail; the new law prompted the Chinese-owned platform TikTok to suspend operations. Kremlin authorities have blocked access to Facebook and Twitter.

Russians are scrambling to learn more about what is happening and what they can do. Should they obey their country’s laws, or defy them in acts of conscientious objection? Should families remain in their homeland or try to flee? Their decisions will be a test of the power of propaganda in a social media age, and of the ability of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s regime to shape values and beliefs strong enough to withstand crisis. Many theorists claim that hard times can lead to citizen protest, and sometimes even to political change. But the Kremlin is banking on its ability to control the message and, instead, fuel a sense of outraged unity.

What do Russians really believe? During the first two weeks of fighting in Ukraine, many journalists reported that most Russians believed official propaganda and did not even know their country was at war. Powerfully written accounts of daily life in St. Petersburg documented citizen willingness to parrot state media tropes. For them, the “special military operation” Putin announced was strictly about “good” Russian soldiers engaged in acts of “defense,” “liberation,” and “peacekeeping.” In a BBC piece, one woman told of phoning her family in Russia while trapped in a bombardment in Kyiv, only to be rebuked for hysteria, as her mother assured her that Russian troops would never attack the Ukrainian capital.

However, history and psychology suggest that the issue of “belief” in propaganda is not straightforward, and that the majority of Russian society cannot simply be dismissed as “brainwashed” by the Putin regime. Russian people do not have a record of gullibility, but rather a long tradition of irreverent humor and coded criticism of dictatorial power discernible only by “reading between the lines.” Soviet archives are packed with letters from the 1920s, written by peasants who only a few years earlier had learned to read, challenging the truth of newspaper stories about all manner of topics relating to the condition of the countryside. More recently, the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer, a survey conducted in 28 countries, identified Russia as the nation with the lowest level of trust in media, reaching only 29 percent.

Such statistics indicate that Russians might not believe official media, but might also choose—perhaps subconsciously—not to acknowledge the extent to which they allow themselves to be deceived. (It bears mentioning that social media analysts of the 2016 US presidential election noted a similar phenomenon: Citizens can, and often do, choose to believe comfortable falsehoods, instead of admitting to truths that disrupt their desired way of seeing the world.) Looking at Russian television news after the takeover of Crimea in 2014, journalist Maria Lipman concluded that the more extreme and far-fetched the claims of various programs became, the more their audiences grew. “Russian viewers tuned into shows,” she and two colleagues argued in a 2018 essay, “in search of not truth, but emotional gratification.” Viewers wanted to believe wildly distorted media stories that affirmed “national pride and a sense of vindication.”

This situation of willing self-deception, some suggest, starts at the top, and is likely affecting the Russian president. Oligarch-turned-dissident Mikhail Khodorkovsky describes Putin as a man living in a fantasy world, unwilling to use the internet, surrounded by people who tell him only what he wants to hear. According to celebrity novelist and Kremlin critic Boris Akunin, a resident of Moscow until 2014, Putin genuinely expected jubilant Ukrainians to welcome Russian soldiers with flowers, and now cannot accept that he has made a calamitous mistake.

The Russian people, taken by surprise at news of the invasion, may be similarly holding onto explanations that help keep chaos at bay. Russian sociologist Grigory Yudin, who was arrested at one of the first anti-war demonstrations and beaten so badly he had to be hospitalized, says he understands the hesitation of fellow citizens to speak out. In an interview with the independent news agency Meduza just days before its Russian office was forced to shut down, Yudin explained: “After a shocking event you’re ready to accept any convenient interpretation on offer. [Here] many people are clinging to the most immediate explanation, courtesy of government propaganda. That’s the most comfortable choice.”

Speaking to popular Russian YouTuber Yury Dud, Akunin predicted most Russians will try to retreat into family life—a phenomenon that can be seen across many Russian social media accounts. The Instagram page of one Moscow resident features a picture of a family ski trip in Sochi, reading “Here it is so easy not to think about war, not to get hysterical, and not to be afraid. Here at least something depends on you.” Even this comment has been restricted to a small group of relatives and friends.

Ukrainian journalist Dmitry Gordon thinks such a trend will continue. “Honestly, I don’t believe that Russians en masse will go into the streets,” he said last week as he interviewed Khodorkovsky. “It’s obvious to me that if, today, half a million or a million people turned out in Moscow, Putin would be finished.”

Former oligarch Khodorkovsky, who spent 10 years in jail for opposing Putin, disagreed, but admitted that rallying dissent in Russia would take time. He cited polling statistics in which 88 percent of Russians said they were for peaceful relations with Ukraine, but 66 percent simultaneously said they supported the war. Such mutually incompatible results, he claimed, reveal a society wracked by self-delusion, in which many people are “unwilling to see and hear” realities they would find personally devastating. But contradictions of this magnitude, he argued, are difficult to sustain.

In his Meduza interview, sociologist Yudin maintained that, eventually, even citizens who would prefer to hide from politics will come to realize they face a moral obligation. “There are times when you have to accept your powerlessness to change the world as a whole and figure out what you’re personally responsible for—in such a way that afterward you’re able to live with yourself, that you can stand to look at yourself in the mirror,” he said.

“Educating” the public. In this environment, both dissidents and state actors are conducting efforts to “educate” the broader public, launching rival public relations campaigns aimed at convincing ordinary people that groups of dangerous “others” are trying to deceive them. The Ukrainians, for their part, have mobilized sports heroes once enormously popular in Russia to appeal directly to former fans. Now fighting in defense of Kyiv, Ukrainian heavyweight boxing champions and brothers Vitali and Wladimir Klitschko are taping messages in Russian, as well as Ukrainian and English, urging listeners to help stop a “senseless war” that they vow “no one can win.”

Ukrainian forces also allowed—or instructed—a captured Russian policeman to answer questions at a press conference, where he eloquently spoke of being misled by his superiors, who had convinced him that Ukraine was in the hands of fascists and that its citizens were suffering “under the Nazi yoke.” However, he added, he had only himself to blame: “We had internet, sometimes we came across other sources, we could have done a little analysis… In the end, we thought too little for ourselves. We brought sorrow to this land.” He urged his fellow soldiers not to disgrace the memory of past Russian heroism and to open their eyes, show courage, and refuse to participate further in the war.

But the Russian government is fighting back—including, after a late start, in the realm of social media. On March 8, the Russian Ministry of Defense launched an English-language Telegram channel. Its Russian-language Twitter page, accessible only to registered users, shows a series of poster prototypes built around the letter “Z,” an emblem painted on Russian tanks entering Ukraine—which are now being posted by officials across the Russian nation. “Z” is the first letter of the Russian word “za,” meaning “for,” and each giant “Z” poster seems to explain what the country is fighting for just a little bit differently, albeit always with a positive spin: “for victory,” “for the children of Donbas,” “for truth,” and “for peace.” Duma member Maria Butina, convicted in the United States in 2018 of acting as an unregistered Russian foreign agent, posted a video of herself drawing a “Z” on her suit jacket in honor of Kremlin forces. Other pro-Putin demonstrations of online support show groups of Russian workers in black T-shirts with a “Z” insignia, underneath the hashtag “We Don’t Leave Our People Behind.” In one, a man tells viewers that “the special operation of Russia in Ukraine is the consequence of the death of more than 14,000 people in the Donbas.” He castigates protestors for not supporting the country’s troops, “heroes” engaged in “once again defending Europe from Nazism.” The clip ends with a crowd chanting: “For Russia! For the president!”

It is difficult to tell how much of this is genuine. After mapping more than 20,000 Twitter interactions, disinformation specialist and scholar Marc Owen Jones found bot networks at work, as well as “lots of inauthentic behavior” driving “I stand with Putin” and “I stand with Russia” hashtags, which were predominantly linked to tweets “painting Putin as somehow standing up to the West.”

Thread 1/ This is a thread on pro-Russian propaganda & #disinformation. I analysed the hashtags “i stand with Putin” & “i stand with Russia’. I analysed around 20,000 Twitter interactions involving 9600 unique accounts

Bots ✔️

Engagement Farming ✔️#UkraineRussianWar #Ukraine pic.twitter.com/I8XBwPlc7b— Marc Owen Jones (@marcowenjones) March 3, 2022

Virtually overnight, the Russian version of Facebook, VKontakte, has been flooded with similar pro-Putin hashtags, some from bot accounts (pages with no personal posts, only reposts), but many from schools and local councils across Russia. It appears all government agencies with official VK pages have been asked to voice enthusiasm for the country’s armed forces, posting photos of people standing in giant “Z” formations or spelling out patriotic slogans. Such images are typically accompanied by statements such as that offered by St. Petersburg Gymnasium #92: “We support those who are carrying out their military duty and defending the interests of our country.” The St. Petersburg Regional Police Force has posted an exceptionally high-production-value video, combining shots of combat equipment with clips of individual officers carrying out different types of duties in different locations, each reciting a few lines from a long patriotic poem.

Meanwhile, government television makes no mention of the “No to War” graffiti sprayed across Moscow and St. Petersburg or the frantic efforts of authorities to erase all renegade protest slogans. A Meduza editor was able to post to Twitter photos of city utility workers dumping buckets of blue paint on ice, in a poorly conceived attempt to conceal a giant “No to War” sign carved into the surface of the frozen Moyka River.

“Not to war” carved into the ice on the Moyka River in St. Petersburg. Apparently city utility workers tried to paint it over — looks like they didn’t bring enough paint. pic.twitter.com/FNJVp8wIIF

— Eilish Hart (@EilishHart) March 6, 2022

Since the invasion, official news coverage of the war has shifted from spin to outright falsification, with—as in 2014—stories designed to fuel grievances against the West and, above all, the United States. Talk show host Vladimir Soloviev has claimed that the Washington establishment runs 13 secret bioweapon laboratories on Ukrainian soil—a fiction apparently derived from warnings issued by Western scientists that a Russian attack on several US-linked Ukrainian labs involved in public health and animal research could risk the release of “dangerous pathogens.” (The Russian media outlet RT picked up on this story again on March 8, broadcasting a clip of US Under Secretary of State Victoria Nuland testifying at a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing that “Ukraine has biological research facilities, which, in fact, we are now quite concerned Russian troops, Russian forces may be seeking to gain control of.”)

Other stories claim Ukrainians are manufacturing nuclear “dirty bombs” with US knowledge. The battle at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant on the night of March 3-4, watched on the plant’s livestream YouTube camera by millions, was explained as an act of Russian self-defense. The fire that broke out on its perimeter was attributed to “Ukrainian saboteurs” so determined to “make Russia look bad” that they planned to cause a nuclear explosion.

“Fighting” fake news. Amid these garish headlines, some Russian government ministries seem to be trying less to inflame public outrage, than to calm citizens down—ironically accusing the West of planting false news stories intended to inspire fear. Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has launched a campaign seemingly designed to discredit any independent reportage at variance with official claims—but organized around Western-style warnings of fake news. “The unprecedented stream of #fakenews on what is happening in #Ukraine is designed to stir emotions. & shut down one’s rational thinking,” a tweet from the ministry read. “We do not want ordinary people to feel anxious and panicked because of information wars,” it wrote on its new website waronfakes.com, which “debunks” media stories published in five different languages, including English, Arabic, and Chinese. The project also includes an elaborate multimedia Russian-language Telegram channel.

These sites play up Kremlin claims that it is a victim, rather than a practitioner, of information war. “Malicious” United States outlets are accused of “fabricating” claims that, for example, Russian soldiers fired on civilians trying to leave the encircled Ukrainian city of Mariupol—despite a number of highly documented incidents condemned around the world. As Western news filled with reports of Russian shelling of humanitarian evacuation corridors, Russia’s Channel One television station ran a story in which purported Mariupol refugees instead recounted how they were “shot in the back by Nazis” while trying to escape the siege.

When challenged in the past about the accuracy of its media coverage, Russian officials have often claimed that so-called “Western bias” is just as bad. Such a comparison today ignores the multiplicity of journalistic voices available to Western audiences and the commitment to accuracy embraced by courageous correspondents in the field. In the weeks since all-out combat began, Russia’s “alternate reality” media universe has grown so extreme that on March 8 Ukraine’s UN Ambassador advised all Kremlin diplomats to seek emergency mental health help, after reading aloud a Russian government tweet that claimed the country’s military had entered Ukraine only to “prevent” a war.

omg. The Ukrainian Ambassador holds up a tweet from Lavrov (saying Russia is in Ukraine to stop a war) and advises Russian diplomats where they can get mental health assistance. pic.twitter.com/SEHXltCL7V

— Mark Elliott (@markmobility) March 8, 2022

Nevertheless, all major powers observing this conflict have arguably been engaging in elements of wartime PR, albeit in far less extreme ways. Military and media analysts alike have been increasingly wondering whether US emphasis on Ukrainian combat success and Russian military failure are distorting public expectations and hindering a more “realistic” negotiated peace.

Countries like China have been using the conflict to critique US global leadership. After President Joe Biden announced a ban on Russian oil imports, Hu Xijin, a commentator for China’s Global Times, tweeted that it was “hard to say” whether Biden’s actions, taken “without the support of the EU,” were “a manifestation of strength or lack of it.” Minutes before Biden’s statement, Hu accused the US president of trying to “up the ante of confronting Russia” while ignoring Kyiv’s alleged increasing willingness to compromise. He linked his statement to a screenshot of two sentences of a story on an unidentified Turkish news site, which claimed Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky “had lost interest in joining NATO” and was potentially willing to accede to all of Russia’s territorial demands.

In such a world of claims and counterclaims, multiple countries are speaking of the need to educate children about the war. In the United States, colleges, universities, and institutes have already held countless informational events, and the web is full of resources for primary and secondary school teachers with titles like “Talking to Kids about Ukraine.” Russia says it is similarly concerned. More than half a million students reportedly attended a March 3 webinar organized by the Russian Ministry of Education, titled “Defenders of Peace” that promised to teach “all Russian schoolchildren” about the “truth” of the conflict. In addition to helping students understand the alleged facts on the ground (“how NATO poses a threat to Europe” and “why Russia decided to intervene to help peaceful civilians”), the webinar raised concerns common to many Western educational establishments, warning of the dangers of “fake news.” Chillingly, the ministry’s professed desire to help students learn how to “distinguish truth from lies amid the giant stream of information, photos, and video clips that can be found online” mimics Western language on media literacy, but in the service of state-manufactured deception.

From propaganda to mass repression. Where does this internal information war leave Russia? Certainly, some citizens are trying to rally resistance. More than 4,500 demonstrators were arrested on March 6 alone. Radio Free Europe, announcing on Twitter it had been blocked by Russian censors, posted Russian-language instructions for where to download and how to install free VPNs—virtual private networks that allow users to mask their location and anonymously connect to the internet as if they were living outside the country. Russian journalist Dud embedded a similar message for his almost 10 million YouTube subscribers inside his most recently posted interview.

1/? If you are in Russia, you may not be able to access RFE/RL content. The Kremlin has imposed unprecedented censorship. Here’s how to bypass it.

— Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (@RFERL) March 6, 2022

According to Steven Barnes, a Russian history professor at George Mason University who has worked closely with museums dedicated to preserving the memory of the Stalin-era Gulag, “regional civic activists, many of whom have already been harassed by local authorities for years for their efforts to preserve memories of the darkest days of the Soviet past, are taking great personal risk in making anti-war statements on social media. They are posting the Ukrainian flag on their profile pictures, praising Ukrainian cultural figures, or quoting anti-war poetry.”

These local activists have found themselves, oddly, on the same side as oligarchs Mikhail Fridman and Oleg Deripaska in speaking out. Deripaska, an aluminum magnate once considered so close to Putin that he was sanctioned by the United States in 2018, has gone so far as to condemn the war on Telegram in Russian, on Twitter in English, and in a speech at a March 3 economic conference in Siberia. He warns that economic sanctions will destroy Russia and change the world forever, writing “We have already passed the point of no return.”

Such pronouncements carry risk. When Moscow-24 state TV presenter Vyacheslav Tikhonov, reporting live, urged people to avoid pasting toilet-paper Zs to the back windows of their cars, saying such displays “limit visibility” and could increase the risk of accidents, he was summarily fired. Independent journalist Farida Rustamova, formerly of the shuttered Meduza and TV-Rain, claims that while a number of central bureaucrats profoundly object to Putin’s decisions on Ukraine, most do not believe his power is weakening and that their disagreement, if publicly expressed, would bring about change. In her first Substack newsletter, Rustamova quoted a source close to the Kremlin as saying that “many understand this is a mistake, but in the course of doing their duty come up with explanations in order to somehow come to terms with it.”

In his interview with Dud, author Akunin predicted that soon “propaganda will not be enough” for the Putin regime to hold on to power, and mass domestic repression will follow. Asked for this article whether resistance has a greater chance of succeeding in Russian regions further away from Moscow controls, historian Barnes was pessimistic. “In some places the repression will be much worse, because it will take place far from the eyes of foreign media. In others, local authorities may themselves be unhappy with the war and may tolerate open dissent to a greater degree. However, I fear that the former situation will be far more common than the latter, as officials who depend upon patronage from Moscow try to prove their loyalty to Putin by demonstratively acting to squelch those who speak out.”

Asked whether the situation in Russia could possibly generate political change, similar to the unraveling of Communist power in East Germany in 1989, political scientist Dietlind Stolle, a professor at McGill University, expressed doubt. Stolle grew up in the East German city of Rostock and worked as a journalist there from 1985 to 1989. At that time, she points out, the resistance movement had an organized leadership and could use churches as an institutional base. She recalled that “back then, we actually had no idea how our government and the Soviet Union would react during the first demonstrations for greater civil liberties and freedom of speech. But unlike Russia today, the East German regime was not involved in a hot war.”

Despite the differences, however, Stolle emphasizes that what she calls the “large collective action dilemma” for citizens is the same today as it was then. “As [economist] Timur Kuran and others describe, we do not know the preferences of others in dictatorships,” she says, “so we are less likely to turn out because we believe others will not, or that others are not as critical of the regime, or in this case of the war, as we ourselves are.” East Germany, she argues, benefited from the idea of glasnost, or openness, promoted by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, “which encouraged people to share more and allowed collective action to happen, even with the dangers.”

Russians, she concludes, need opportunities for more discussion and greater social trust. “Misinformation, the closing of alternative information channels, all make it harder for them to organize and inform themselves and exchange opinions. Right now, it is much more convenient for Russians to believe the regime’s lies. Psychologically it is easier to ignore reality and trust propaganda. Until they begin to see the damage this war brings to their own world, their own society, and their sons.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Russia, Ukraine, information war, media

Topics: Disruptive Technologies, Nuclear Risk

This is exceptionally informative (and terrifying). Thank you.