Why al-Zawahiri’s death should focus attention on nuclear terrorism—foreign and domestic

By Scott Roecker, Nickolas Roth | August 15, 2022

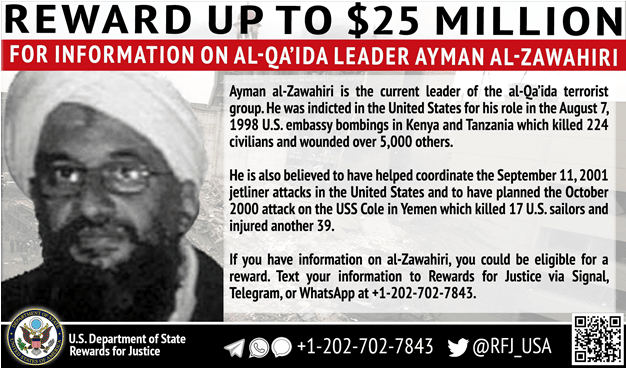

Bounty flyer offering $25 million for information about al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. Photo credit: US State Department

Bounty flyer offering $25 million for information about al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. Photo credit: US State Department

The news that Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader of the al-Qaeda terror group, was killed in a drone strike is not just a counterterrorism victory, but also a win for those seeking to prevent catastrophic nuclear terrorism. Al-Zawahiri’s role in the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center is well known, but his role in supporting al-Qaeda’s elaborate attempts to acquire a nuclear weapon is less well publicized.

The threat of nuclear terrorism is not hypothetical. Government officials over many decades have agreed that a relatively sophisticated, well-financed violent group could build a nuclear weapon if it acquired sufficient quantities of weapons-usable nuclear material. Also, there have already been successful attempts to sabotage of nuclear facilities. For example, in August 2014, an insider at the Doel-4 reactor in Belgium sabotaged one of the plant’s turbines leading to the plant’s shutdown for months.

Al-Qaeda’s nuclear program began in 1998 following Osama bin Laden’s fatwa that called on Muslims to “kill the Americans and their allies—civilians and military” and his ascension as leader of the global Jihadist movement. Under the direction of al-Zawahiri—who served served as al-Qaeda’s second in command when bin Laden was alive and advocated for destroying US “history, power balances, strategic and military doctrines, and global order”—al-Qaeda attempted to acquire nuclear weapons and considered targeting nuclear power plants in the United States. Bin Laden and al-Zawahiri specifically discussed nuclear weapons with two senior Pakistani scientists they tried to recruit. Public reports indicate the program went as far as conducting explosive tests in Afghanistan, consistent with the development of a nuclear weapon.

Some might assume that al-Zawahiri’s death and the decline of al-Qaeda over the past two decades means that nuclear terrorism threats are no longer a concern. Or people may think that the apocalyptic ideology and rhetoric that provided the justification for al-Qaeda’s nuclear ambitions are unique to Islamic jihadism. Those would be wrong conclusions.

This type of extreme, apocalyptic thinking exists among domestic terrorists in the United States today and needs more attention. There is a growing threat of politically motivated violent extremists in the United States, and some of those domestic extremists have ambitions similar to al-Qaeda’s. These extremists, often known as accelerationists, view societal collapse as inevitable and seek to ignite a “total revolution” that would level the existing system of governance.

Brandon Russell, a former Florida National Guard member and co-founder of the accelerationist group Atomwaffen Division (which translates from German to “the nuclear weapons division”), was arrested in 2017 while heavily armed en route to the Turkey Point nuclear power plant. Several years before Ashli Babbitt was killed while storming the U.S. Capitol as part of a right-wing uprising on January 6, 2021, she was an employee of the Calvert Cliffs nuclear plant, where she exhibited violent behavior. Matthew Gebert, then a State Department employee, secretly headed a chapter of the white supremacist group The Right Stuff. In May 2018, while working for the State Department, Gebert said on a white nationalist podcast that “[w]e need a country founded for white people with a nuclear deterrent. And you watch how the world trembles.” Although they were not backed by al-Qaeda’s combination of apocalyptic ideology, resources, and technical sophistication and appeared unlikely to succeed, these people and incidents linked to them likely do not provide a complete picture of the threat.

Like al-Zawahiri’s nuclear ambitions, those demonstrated by domestic US terrorists underscore why policymakers should support programs and policies designed to protect nuclear facilities from theft and sabotage. In particular, the US government should redouble efforts to eliminate vulnerable nuclear weapons-useable material in any country or facility, at home and abroad, and increase funding for US programs that strengthen security at nuclear facilities worldwide.

Insider threats need to be reevaluated, as well. Although US nuclear facilities have elaborate programs to screen candidates and to monitor employees who could potentially pose a threat, there is reason to question whether those programs are sufficient to the threat. The January 6th attack on the Capitol revealed critical vulnerabilities in the US government’s security systems. In response, the Biden administration released the first ever National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism in June 2021. Since then, many departments within the US government, and in particular the Defense Department, have taken important steps to enhance monitoring of extremist activities amongst employees.

Despite the clear need for action, both commercial nuclear plants and government-run nuclear facilities responsible for weapons research, production, and deployment in the United States have not revealed what, if any, steps they have taken in recent years to enhance their protection against insider threats. Neither regulators nor political leaders have called for or required greater security.

Ayman al-Zawahiri is dead, but the violence he perpetrated, the apocalyptic ideology he promoted, and the nuclear threat he posed lives on in a new generation of terrorists—here and abroad. As long as nuclear weapons and materials exist, governments must vigilantly defend against this threat and policymakers, like those in Congress, must provide the oversight and resources needed to adequately protect US nuclear facilities.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.