This article is part of a Bulletin special feature on the hazards and potential of geothermal energy. Read Jessica McKenzie's full report »

The geothermal moonshot

November 7, 2022

By Jessica McKenzie

This article is part of a Bulletin special feature on the hazards and potential of geothermal energy. Read Jessica McKenzie's full report »

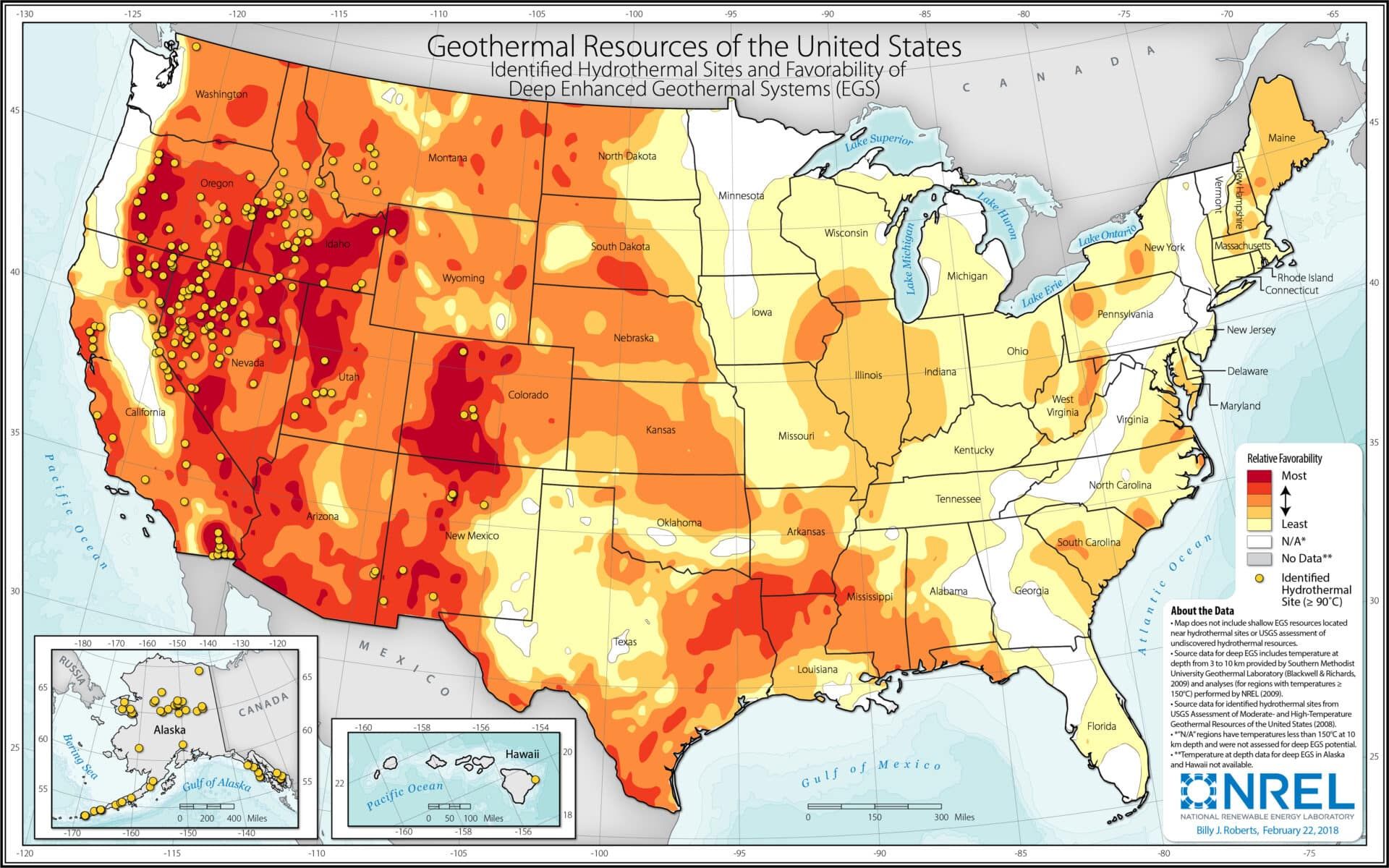

From his home office in Carson City, Nevada, Paul Schwering monitors an old gold mine in the Black Hills of South Dakota, approximately 1,000 miles away and a mile underground. What was once the Homestake Gold Mine has been repurposed as a research station for enhanced geothermal systems, also known as engineered geothermal systems, a technology that could increase the United States’ geothermal power generating capacity 40-fold. Energy experts estimate that geothermal energy could contribute up to 10 percent of US electricity generation, but only if researchers can figure out how to make enhanced geothermal systems work on a large scale.

Enhanced geothermal systems have been called the “geothermal moonshot.”

“This is probably decades away,” James Faulds, the Nevada state geologist and director of Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, says.

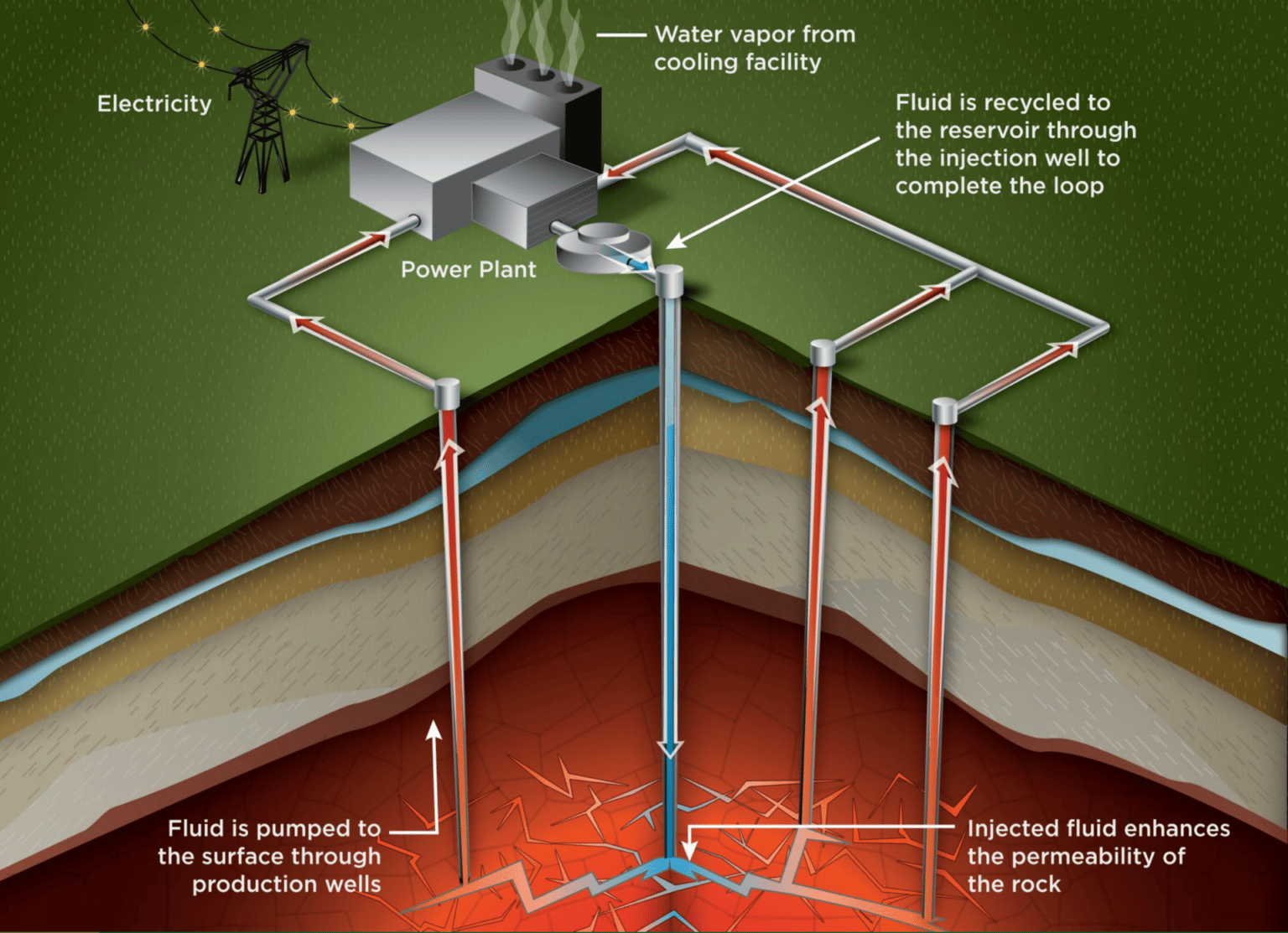

The idea is simple, even if implementation is not: If the perfect conditions for geothermal energy production don’t exist, make them. While a natural geothermal system has high heat, water, and permeability—the three ingredients needed to make electricity from the Earth’s energy—an enhanced or engineered geothermal system will often just be very hot. Humans must intervene to add water and permeability. That starts with fracturing the rock, also known as “stimulating,” a process not unlike the oil and gas industry using hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to extract oil and gas from shale rock.

That’s what Schwering is studying in South Dakota, at the Sanford Underground Research Facility, where researchers are using hydraulic fracturing to break apart crystalline rock deep underground. The researchers then inject water and observe what happens. They are hoping to prove that it is possible to artificially create an underground system where water can be injected from the surface, flow through the broken rock—becoming heated in the process—and subsequently be pumped out at temperatures hot enough to generate electricity, as at geothermal plants built on naturally occurring geothermal systems.

The process is not without risks, most notably the possibility of induced seismicity, or earthquakes. Hydraulic fracturing can sometimes increase seismic or microseismic activity. In 2017, an enhanced geothermal systems project in South Korea caused a 5.5 magnitude earthquake in Pohang, the largest-ever earthquake linked to an enhanced geothermal system. In that case, reinjected water activated a previously unknown fault line, triggering the earthquake. Dozens of people were injured and over 1,700 residents had to move into emergency housing.

If enhanced geothermal systems can be proven to be safe and cost-effective, the potential is huge, and not just in terms of electricity production. If used to support direct-use applications like district heating, the Energy Department estimates, enhanced geothermal systems could theoretically heat every US home and commercial building for at least 8,500 years.

Continue reading Jessica McKenzie's feature on the hazards and potential of geothermal energy: "Showdown in Dixie Valley."

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows, nuclear threats are real, present, and dangerous

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: climate, geothermal, geothermal power

Topics: Climate Change

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

Quaise Energy (Boston) and PLASMABITS (Slovakia) are developing plasma-based deep geological drilling rigs that melt/vaporize through rock much faster than mechanical drilling. Quaise thinks their tech can drill 12 miles/20 km deep in as little as 100 days, to rock at least 400° and perhaps as hot as 500 °C, for supercritical operation at maybe twice the efficiency of most “high-temperature” geothermal generation. Being able to drill almost anywhere and hit hot rock will mean being able to “re-fire” most coal-fired power plants with wells drilled right on-site. Deep drilling plus the enhancement tech described in this article will lower… Read more »