Why the Pentagon should “surge” investments in pathogen early warning systems

By Christine Parthemore, Andrew Weber | April 14, 2023

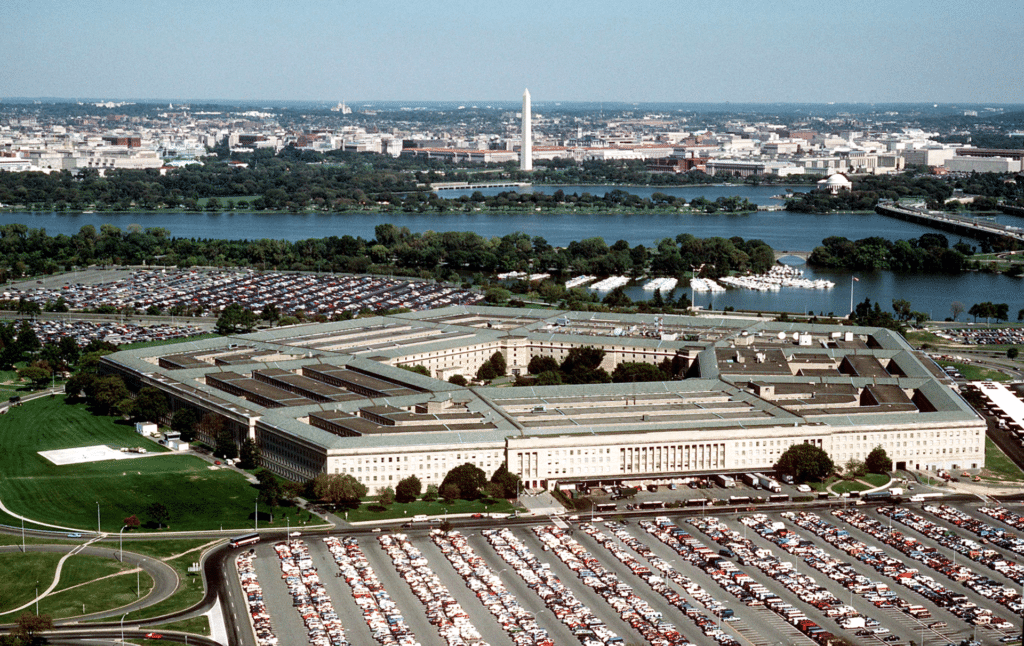

The Pentagon has a chance to improve its pathogen early warning systems, an important element of protecting troops and the public from biological threats. Credit: US Department of Defense.

The Pentagon has a chance to improve its pathogen early warning systems, an important element of protecting troops and the public from biological threats. Credit: US Department of Defense.

The Pentagon may soon release its first-ever Biodefense Posture Review, a study that will assess how prepared the Department of Defense is for future pandemics or the threat of bioweapons use. In our past work, we supported an early wave of efforts to dramatically expand US government biosurveillance capabilities—systems to detect and understand biological threats as rapidly as possible. Given how impressively (and cost-effectively) such capabilities have advanced and scaled since that time, the forthcoming review is an opportune time to kick off a new surge to dramatically accelerate the US military’s pathogen early warning efforts.

This surge would not only serve to protect the health of US forces—which alone would justify the investments; these tools would also help deny the military and strategic effects of biological weapons and thereby help deter hostile nations from developing or using them—a classic military deterrence by denial approach. Doing so is an increasing concern given real-world dynamics—including the threat that Russia might use biological or chemical weapons in Ukraine. Indeed, the past year of war drives home the need for deploying the tools that could help dissuade such a use.

While there is much to do, there is a strong foundation on which to build. The US government has been expanding its pathogen early warning efforts for over a decade, across administrations of both parties. When former President Barack Obama signed the first National Strategy on Biosurveillance in 2012, significant early warning efforts were already underway across multiple departments. This included an expansion of biosurveillance efforts during a multi-year exercise between the US and South Korean governments known as Able Response, an endeavor that enabled the two countries to improve preparedness for urgent biological events. After COVID-19 revealed that international biosurveillance systems were still fragmented and much slower than they needed to be to respond to an unexpected crisis—a crisis which has left almost seven million people dead worldwide—the US government and many others decided to once again commit to harnessing the most recent advancements in the early warning toolkit to prevent future outbreaks. A hallmark of this work is the new Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics launched by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2022. Today, early warning efforts benefit from great leaps in diagnostics and genomic sequencing that have been decades in the making, as well as cloud computing and countless other enabling technologies.

This context—a mix of strong progress and urgent need for improvements—has required the professionals conducting the Biodefense Posture Review to consider what should come next for the Defense Department in pathogen early warning. We recommend, first, that the Defense Department optimize its structure of roles and responsibilities for pathogen early warning. Based on changes made in 2020, the Defense Health Agency is currently tagged as the lead. It has the advantage of already caring for and collecting data on service members. Yet given how rapidly the technologies to enable early warning are improving, the Pentagon faces the increasingly pressing question of whether direct leadership from the science and technology and acquisition arms of the Pentagon are a better fit.

Indeed, relevant activities already lie in the Chemical and Biological Defense Program that can help develop, purchase, and deploy new tools to meet defense-specific needs. This program and related parts of the Defense Department also implement early warning work with other nations, including in regions like Ukraine and South Korea, where the US government suspects nearby adversaries of having offensive biological weapons programs and/or where large numbers of US defense personnel are deployed. Hopefully the Biodefense Posture Review will address which parts of the Pentagon are best positioned to pick up on the technologies the private sector and academic labs are developing that could be important to the wide-ranging efforts that comprise early warning.

Second, if it hasn’t already, the Defense Department should create a roadmap for augmenting existing early warning capabilities across bases and deployed platforms. This work can include relatively easy-to-implement activities such as conducting wastewater sampling for pathogens at as many bases as possible using existing commercial systems.

Certain bases should become testbeds for hosting cutting-edge tools, such as emerging metagenomic techniques to analyze all the genomic material in a sample, new environmental monitoring equipment, advanced data analytics, and more. The objective should be to quickly achieve greatly improved, disease-agnostic detection capabilities to the best degree possible. The selected locations for this game-changing capability should have vulnerability to natural and deliberate disease threats and be important to the continuity of defense operations, military readiness, or national incident and emergency response.

The Defense Department will need to then tailor the best approaches for its varied installations based on their geographies and missions. Not every base needs to employ the most cutting-edge approaches to early warning available today, even if that should be a longer-term goal. For example, while some bases should be using disease-agnostic technologies to find every possible pathogen now, in the near term combinations of wastewater and environmental sampling, health-monitoring wearables, digital detection, and other tools may be the best fit. Of course, the Pentagon should still commit to improving every base’s pathogen early warning in the coming years.

Third, the Defense Department needs to revamp its Biological Threat Reduction Program and make expansion of early warning-related partnerships around the world one of its top priorities. Successive administrations, unfortunately, cut the budget for this important program between 2015 and 2020. The program, which has always included biosurveillance activities, is part of the Cooperative Threat Reduction Program created to dismantle the former Soviet Union’s weapons of mass destruction and redirect weapons workers to peaceful pursuits. It’s proven to be a cost-effective way to strengthen relationships with other nations, yet it still suffers from insufficient resources.

In just one example of what seems to be a regrettable pattern, on a fall 2022 visit to Tbilisi, Georgia, we learned that the Department of Defense may be ending most biological threat reduction cooperation with this close and decades-long partner. US collaboration with countries like Georgia has led to direct improvements in our own technologies and understanding of how to create effective early warning systems for biological risks. Yet policymakers are considering reducing or ending such important work due to budget pressures and other factors. That would be shortsighted.

The Pentagon should ensure that collaboration with these longtime biodefense and health security partners—including Ukraine—continues. After all, competitors would happily become closer partners with these nations in the absence of US collaboration. And ensuring strength in the Defense Department’s bio programs with partners around the world is even more critical now that Russia, having invaded Ukraine, has repeatedly leveled false accusations alleging that the United States and Ukraine have been secretly developing bioweapons. Officials in the United States and Ukraine say the allegations raise concerns that Russia in fact may be plotting to use biological weapons.

Of course, bolstering the US military’s early warning systems will require increasing resources—long overdue after years of declining biodefense investments. Currently, the Pentagon spends less than one quarter of one percent of its budget on biological and chemical defense. The threat of biological weapons posed by Russia and the impact of COVID-19 on deployable military units should be stark reminders that this trend is overdue to be reversed.

By taking these three steps now—and presuming sustained funding from Congress—the Defense Department could directly help maintain the US position as a global leader in biotechnology and undergird sustained military readiness, all while ensuring we can lessen the impact in terms of lives and economic loss from the next deliberate, accidental, or naturally-occurring disease outbreak.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Biological Threat Reduction Program, pandemic response

Topics: Biosecurity

Why is this a job for the military in the first place? Shouldn’t the military rely on the civilian sector, not vice versa?

Yes, the military has bases in many (too many?) parts of the world, but the State Department has embassies and consulates everywhere.

The military already has sponged up too much R and D government money and gets a huge tranch in the current budget. This could be a place to begin reversing that treend.