Failed visionaries: Scientific activism and the Cold War

By Anna Pluff, John R. Emery | August 9, 2023

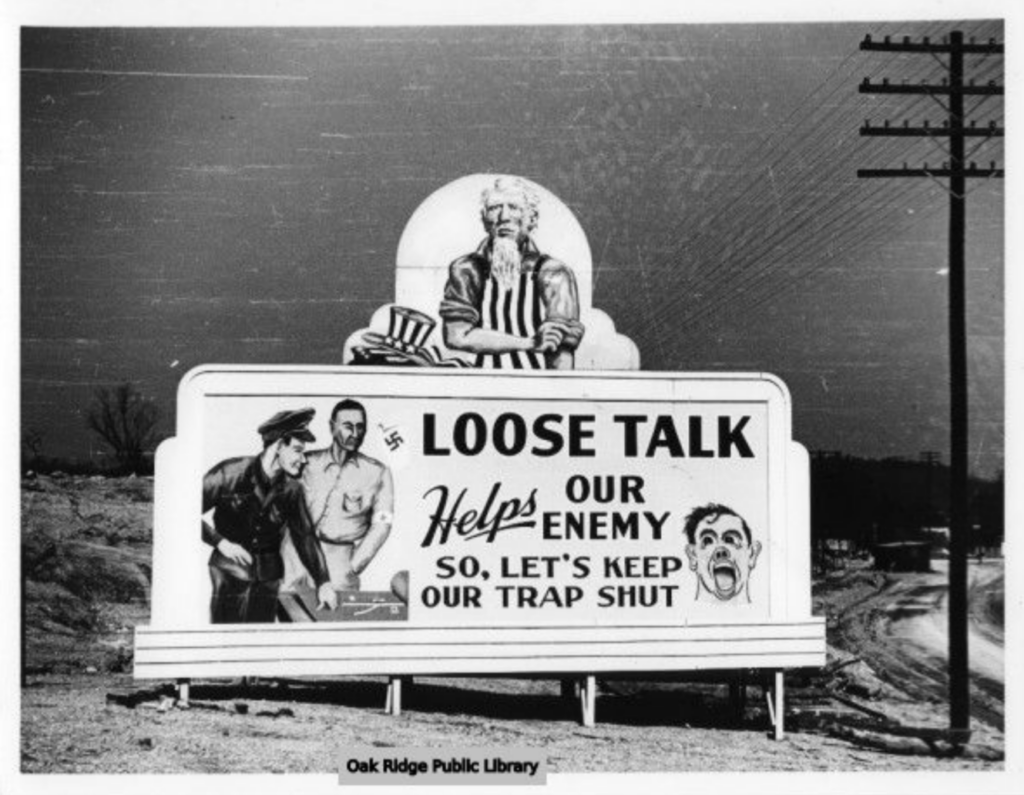

A billboard photographed in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in 1944. The following year, a group of Manhattan Project scientists at Oak Ridge proposed international control of the atomic bomb to create a lasting peace. Credit: US Department of Energy Photograph Collection, Oak Ridge Public Library

A billboard photographed in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in 1944. The following year, a group of Manhattan Project scientists at Oak Ridge proposed international control of the atomic bomb to create a lasting peace. Credit: US Department of Energy Photograph Collection, Oak Ridge Public Library

Even before the Trinity test on July 16, 1945, many atomic scientists involved in the Manhattan Project foretold the possibility of an atomic arms race and anticipated the future of nuclear weapons. A group of scientists at the University of Chicago’s Metallurgy Lab predicted the Cold War arms race dynamics with the Soviets, and the changing international relations the atomic bomb would drive. What became known as the Franck report, penned on June 11, 1945, reiterated that the use of nuclear bombs for an unannounced attack against Japan was inadvisable. There was a recognition that by being the first to release this new means of indiscriminate destruction, the United States would sacrifice global public opinion, launch an arms race, and damage the prospect of reaching any international agreement on the future control of such weapons.

Less than two months later, when Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed on August 6 and August 9, 1945, anxiety swept over both the Manhattan Project scientists and the nation. Questions emerged about how the atomic bomb would fit into a new relationship between science and the state. During World War II, science had found a powerful patron in the military and had grown accustomed to new roles. After the war, scientists’ relationship with the government grew significantly, and prominent scientists joined the upper echelons of the policy-making hierarchy and ushered in a fervent period of activism.

The scientists’ movement began during the war, and by September 1945 the scientists who had worked on the bomb began to organize. Scientists from Oak Ridge in Tennessee took a particular interest in the development of a world federal government––a popular notion at the time––as a solution to the inevitability of nuclear proliferation and its ability to create an increasingly dangerous and unstable world. Extensive archival data from the University of Chicago Library’s Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections reveals the origins of this radical idea, its connections to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, and the unfortunate end to scientific activism in the face of the burgeoning national security state.

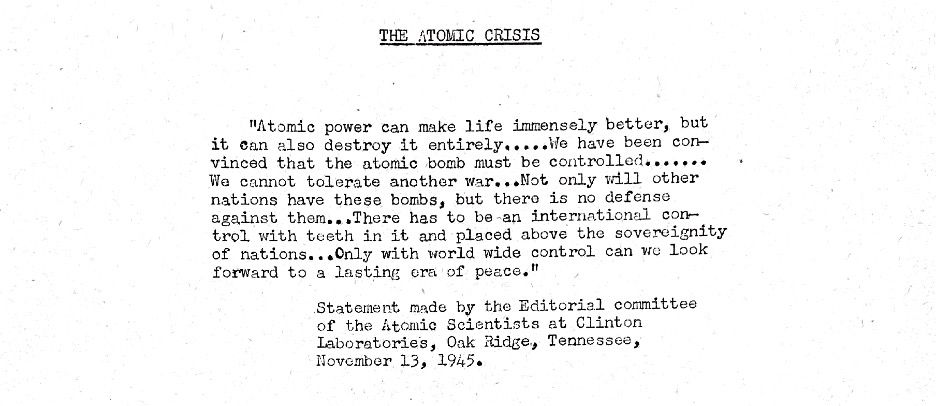

World-government visionaries. On November 13, 1945, the Atomic Scientists at Clinton Laboratories issued the following statement:

Larger associations of scientists formed—like the Federation of Atomic Scientists, the precursor to the Federation of American Scientists—to promote ideas like world government and arms control. Yet activism was a challenge, and the new role of scientist-qua-politician caused some scientists to feel that they had gone too far in abandoning the precept of scientific objectivity. Although some scientists wondered what right they had to speak about political issues, scientists like Harold Urey stressed their rights as citizens and their unique ability to think about post-war implications while the general public had yet to recover from the initial shock of the revelation of this power to the world. Urey also iterated the underlying fear and sheer necessity that brought scientists into politics: “We who have lived for years in the shadow of the atomic bomb are well acquainted with fear, and it is a fear you should share if we are intelligently to meet our problems.”

The scientists’ movement dazzled politicians. Senator Joseph H. Ball of Minnesota announced before the Cincinnati Foreign Policy Institute, “One of the most hopeful developments in the atomic bomb is that at long last the scientists, who have turned our world topsy-turvy, are becoming interested in politics, which has been following the same rut for a hundred and fifty years.” Politicians became enlightened to the gravity of the problem of military control of atomic weapons and sought out conferences and dinners with the scientists to hear their advice in a more informal setting. Some were simply intrigued by the strange spectacle of scientists in politics and gave them nicknames such as “The Lab Lobby” and “The League of Frightened Men.” The scientists were invited to speak to local business, civic, and religious groups, as the public sought out their expertise and listened to their promotion of atomic energy for peace.

Changing tides. As domestic anti-communism and nuclear fears surged, many government and military leaders, and some scientists, began to recognize scientific genius and talent for maintaining atomic supremacy. As historian Jessica Wang argues, in a twist of fate, scientists were among the first victims of the post-World War II red scare. Their advocacy of scientific internationalism and world government was stymied by the evolving perception of atomic weapons as the cornerstone of American national security.

Cold War constraints on the types of engagement possible for physicists began with the battles over two legislative bills. In October 1945, the Truman administration introduced the May-Johnson bill, which proposed a future for atomic energy that was at odds with the Oak Ridge scientists’ vision of international control. Drafted by the War Department on the assumption that the production of atomic energy must remain a closely guarded national secret, the bill relegated all aspects of atomic energy to military control and mandated heavy penalties for violations. Scientists opposed the bill’s exclusive emphasis on military applications, and they felt that the secrecy regulations left little room for information exchange between nations.

An alternative bill proposed by Senator Brian McMahon on December 20, 1945, emphasized complete civilian control of atomic energy policy. Scientists were only briefly able to rejoice before the McMahon bill was heavily revised after news broke on February 16, 1946, of the defection of Igor Gouzenko in Canada. The “Gouzenko Affair” and the revelation surrounding a Soviet spy ring in Canada sent members of Congress, and the rest of America, into a state of apprehension. Fears that atomic secrets were being stolen by Soviet spies soon engulfed Congress, and the McMahon bill was modified to restrict access to atomic information. The bill, which also created the Atomic Energy Commission, was eventually signed into law as the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 on August 1. The regulatory power of the commission was immense.

Loyalty investigations would prove yet another obstacle to international control of atomic weapons and a viable program of arms control. Truman’s federal loyalty program, announced in March 1947, required the FBI to investigate all government employees—greatly expanding the bureau’s power. The program also legitimized the concept of guilt by association by employing the vague standard of “sympathetic association.”

The Bulletin steps in. Eugene Rabinowitch, editor of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, foresaw that the secret development of the bomb during the war and the ensuing arms race would change the “initial admiration for the men who so dramatically brought the war to an end into fear and suspicion of the same men as holders of real or imaginary ‘secrets’ that may spell security or calamity for the nation.” Scientists would become the first profession in America to be exposed to the wholesale loyalty investigations.

Increasing restrictions on political activities and rising paranoia began to restrict the political activities of American scientists. According to political sociologist Kelly Moore in Disrupting Science, policymakers began to see scientists’ access to scientific ideas as dangerous, as they could be used in national defense. When scientists continued to advocate for civilian control or scientific internationalism, they were accused of subversive activity that was damaging to US security. Furthermore, the scientists could not confirm if they were being investigated, and, until 1953, if their position was terminated due to suspected disloyalty, they did not have a right to hear charges.

The Bulletin spoke out against such scrutiny. Rabinowitch expressed concerns about the “general disclination of those concerned to speak up, which demonstrates their disbelief in the fundamental soundness and fairness of a well-informed public opinion,” arguing that this was an “unhealthy sign in a free society.” More alarmingly, Rabinowitch wrote, “The first step towards totalitarianism is to impress the majority of the people that their best interests are served by keeping their mouths shut.” Rabinowitch’s rhetoric was often based on the dichotomy between scientific freedom and control. The Bulletin tried to warn the public that America was facing a dangerous situation, one in which military domination would act as a detriment to scientific development and international relations.

At the pinnacle of its activism, the scientists’ movement revealed the synergies of science and politics and created an avenue for scientists to inspire and enliven public discourse. Yet the scientists’ movement was an ephemeral development, constrained by the Cold War environment in which it formed. In the end, the Cold War political culture dictated who had the power, and scientists’ enthusiasm to fight back dwindled.

In exploring this history, it is important to understand the perilous position of democracy in a state that emphasized security and distrust over freedom and exchange. However, efforts today like the Physicists Coalition for Nuclear Threat Reduction can create a space in the national conversation for scientists to once again enter the ranks of policy making and use their expertise to advocate for a safer world.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Eugene Rabinowitch, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, loyalty investigations, scientific activism, world government

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, Opinion, Voices of Tomorrow

It would be interesting to comment how much Oppenheimer was implicated in these ideas of the “concerned” scientists, many of them old companions of the Manhattan Projetct. In spite of his hearing and punishment by the AEC and Lewis Struss, the years before he was nearer to the government than to his old fellows. The proximity to Einstein, as it can be see in Nolan’s film, is rather ficticious.