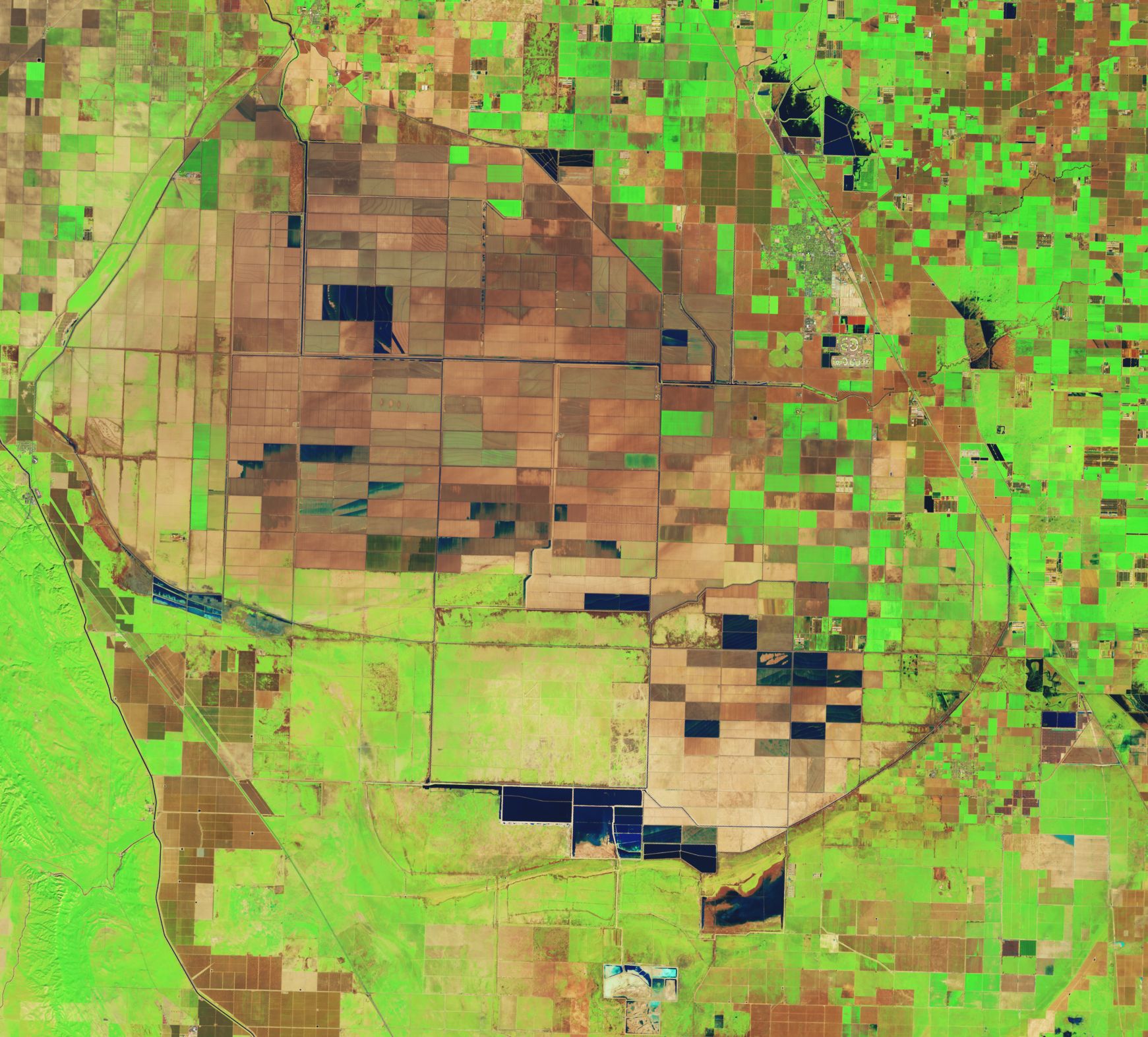

The dramatic impact of flooding from Lake Tulare is visible in this May 7, 2023, photo of California's Central Valley. (Photo by Timothy Swope / Alamy)

How an obscure atmospheric phenomenon causes catastrophic flooding in California

By Chad Small | April 25, 2024

Tulare, California once sat next to the largest lake west of the Mississippi River. During the late 19th century, diversions for municipal and agricultural water use drained the lake dry, and much of the one-time lake bed was repurposed for agriculture. In the century since the lake dried up, it has refilled a handful of times with disastrous results. Last year, the Tulare region—part of Central California’s San Joaquin Valley—was inundated with rain, flooding over 100,000 acres. Projected damages were immense. Nearby farms were looking at over $300 million in losses. Though rare, these floods always have the same culprit: atmospheric rivers.

Atmospheric rivers bring tremendous amounts of moisture from the tropics to the US West Coast. The flood risk of a large-enough atmospheric river can be huge. Christopher Castellano, a meteorology staff researcher at the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes, says “just a couple of events can really make or break your water year.” Lately, California has seen event after event during its winter rainy season, with often catastrophic results—like the refilling of Lake Tulare.

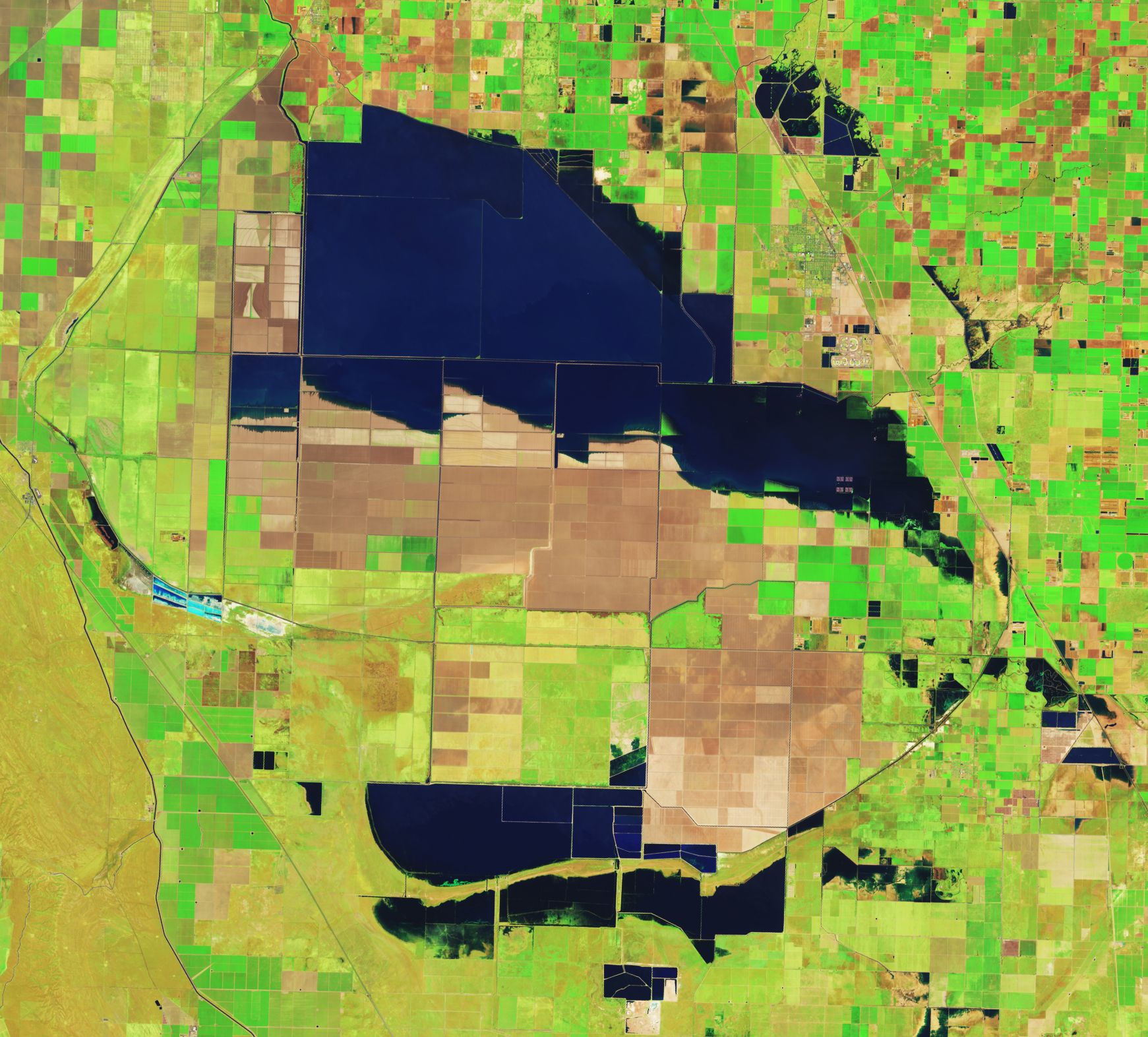

Landsat satellite images in false color show farm fields in Tulare Lake on February 1, 2023 (left), and on April 30, 2023, after the flooding of the lakebed. (NASA Earth Observatory)

Until recently, climate and weather forecasting haven’t been up to the task of giving local and state governments the warnings they need to prepare for atmospheric rivers. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Seasonal Outlook for the first three months of 2023, for example, predicted dryness across much of California. The reality couldn’t have been more different. Record-breaking flooding swamped much of the state last year.

How could the seasonal outlook have been so wrong? It really comes down to what NOAA’s seasonal outlook is capable of predicting. NOAA’s seasonal outlook is based on the expected state of the climate affecting the West Coast—often predicated on the movements of warm water in the Pacific Ocean that create conditions known as El Niño and La Niña. These climate conditions—generally associated with wetter and drier West Coast weather, respectively—can take place over the course of years, far longer than a storm that might last for a few days. This means that the outlook is working to forecast the expected seasonal pattern, while missing heavy rainfall events that could happen on shorter timescales. As climate change progresses, many predictions of what will happen are based on climate, rather than weather, meaning that an atmospheric river-like event can totally upend expectations.

To more accurately predict natural disasters, forecasters—present and future—need a bridge that connects shorter-term weather and longer-term climate. And that bridge needs to be observable and predictable, and be globally applicable. For atmospheric rivers, that bridge is the Madden Julian Oscillation.

History of the Madden Julian Oscillation. In the early 1970s, Roland Madden and Paul Julian, long-time scientists at National Center for Atmospheric Research, discovered a regularly occurring wind pattern that moved heavy rain from the Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific every few weeks. This massive system—covering on the order of 10 million square miles—came to be known as the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO). For many researchers, it’s become the “missing link” reconciling climate impacts with weather impacts. This forecasting space—subseasonal forecasting—is generally defined as “several weeks to below 90 days,” says Shuyi Chen, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington. Chen adds that, globally, the MJO is the only atmospheric phenomenon that dominates on this time scale. This makes it both special and important for weather forecasters.

For someone living in Indonesia, the effects of the MJO can be enormous. When the MJO is in its active rainfall phase, Indonesia often gets drenched. In January 2020, almost 15 inches of rain fell, leading to dangerous flooding in the capital, Jakarta. If you live in the United States, the impacts are indirect, but equally impactful.

MJO impacts on atmospheric rivers also have implications for wildfires in the western United States. If the MJO leads to heavy rainfall in the autumn, shrubs, grasses, and weeds flourish. Once the atmospheric rivers stop, the plants dry out, leaving behind lots of dry fuel. The following summer, the region can be a potential tinderbox waiting to ignite. These extreme weather events are forcing atmospheric river researchers to pay more attention to the MJO.

State of subseasonal forecasting. At the Center for Western Weather and Water Extreme at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, the MJO has become an essential part of the forecasting toolbox. Mike DeFlorio, one of the center’s research analysts, explains that its subseasonal-to-seasonal forecasting group is actively developing forecasting tools that aim to improve prediction of atmospheric river severity. Tracking the MJO’s movements and intensity is an essential part of this work, which could become an alternative or supplement to forecasting tools like NOAA’s seasonal outlook.

“A lot of these seasonal forecasts are not really designed to predict shorter time scale events like atmospheric rivers,” Castellano says. “There’s no way to really bake that into a three-month prediction.”

As DeFlorio notes, many American universities’ and research institutions’ seasonal predications rely primarily on the El Niño or La Niña conditions. Many of these forecasts don’t take the MJO into account, even though it can drastically change weather conditions. As Chen says, El Niño conditions might indicate a dry winter in California, but the MJO could lead to an increase in landfalling atmospheric river frequency over some regions, reversing expected precipitation predictions that are based on El Niño conditions alone.

Work to incorporate the MJO into American forecasting is burgeoning, but it’s slow. In NOAA’s case, some of that lag is more political than technical. The politics of weather and climate in United States is incredibly contentious. Conservative lawmakers in the United States are often more open to funding weather research at the cost of climate research.

Chen says this political climate appears to have recently played a role in NOAA’s decision to move subseasonal-to-seasonal research operations into NOAA’s Weather Program Office. While NOAA’s weather research is some of the world’s best, its Weather Program Office is not fully equipped to do subseasonal research in a way that a climate-specific office would be, Chen adds, hindering the agency’s subseasonal forecasting ability. These political considerations don’t apply to European counterparts, and their forecasting is much better because of it.

Frederic Vitart, a principal scientist at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, explains that as the center focused on improving its forecasting skill beyond a 10-day forecast, the MJO became more and more important. Vitart says that the objective was to ensure that their forecast models could accurately replicate the MJO’s wind and rainfall patterns. If that was successful, forecasts elsewhere in the world also improve because the MJO affects global weather patterns. Now the center can forecast the MJO out to a month which meets the agency’s primary mission of modelling “weather in the extratropics and Europe.” As Chen says, the accuracy of these subseasonal forecasting models is important as it allows “enough time for people to actually make a decision.”

Impacts of not getting this right. Jeffrey Mount, a senior fellow with the Public Policy Institute of California Water Policy Center, notes that 2017 was the wettest year on record in California, and that vast amount of precipitation was almost entirely due to atmospheric rivers. These events did not lead to catastrophe, however.

“The bottom line was this: [the atmospheric rivers] spaced out,” he says. “They were happening like once a week, so things could drain out before the next one came in.”

If the atmospheric rivers had come in quick succession, Mount says, it’s unlikely that California’s storage capacity could have kept up. Utilizing the MJO in subseasonal forecasting makes forecasts of frequency more accurate, giving emergency managers more time to protect the most vulnerable. According to Mount, 2023’s floods around Tulare Lake did not cause as much damage as projected, but the effects among low-income communities were tremendous and lasting.

It took several months for waters from the atmospheric river storms in early 2023 and subsequent snow-melt to fully recede from some of the farmland in Kings County, CA. (Video by California Office of Emergency Services)

“The communities that are at the highest risk of flooding are also the most vulnerable because they don’t have any money,” he explains. “Alpaugh got whacked and because they were poor, they couldn’t do anything about it.”

Alpaugh is a community of just over a thousand people near Tulare. The population is almost 80 percent Latino, with a median income that is $25,000 less than the rest of California’s. In the months following 2023’s tremendous flooding, the community of Alpaugh found itself bracing for the coming summer heat. Heat stress on its own would be a concern for a community that hadn’t yet recovered from flooding, but it could also bring more flooding by melting snowpack in nearby mountains.

Brian Ferguson, spokesperson for the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, noted that these concerns were why the state was paying special attention to the Tulare basin. With the basin already effectively full of rainfall, meltwater from impending heat could make an already dangerous situation even worse.

With limited financial resources, Alpaugh was at the intersection of one flooding event, a heat event, and the risk of a subsequent flooding event. With climate change progressing, these compounding environmental concerns are growing. So too are the needs to understand phenomena like the MJO that can determine how well we can predict longer term trends.

Mount points out that “when it comes to precipitation [California] is the most variable of the lower 48 states.”

“That’s natural variability, and sometimes it varies in our favor, and sometimes it doesn’t,” he continues. Knowing when, and if, that variability brings danger is essential for long term planning under a changing climate. Improving forecasting at the subseasonal level is one of the best ways to accomplish that.

Castellano says that the atmosphere has always been inherently pretty variable. Climate change, however, is changing that variability in ways that could push us into more dangerous—potentially unprecedented—territory. “When you have the right environment, the right conditions come together, you end up with these really incredible extremes that we haven’t seen.”

Design by Thomas Gaulkin. MJO map animation by Erik English, via the Real-Time Atmospheric Rivers and MJO Tracking System developed by Brandon Kerns and Shuyi Chen at the University of Washington. Data from NCEP FNL Operational Model Global Tropospheric Analyses, NASA’s Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG), and TRMM.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: California, atmospheric rivers, climate, flooding, precipitation, weather, wildfires

Topics: Climate Change

Just read about a cloud seeding experiment in the middle east that went sideways bringing unintended flooding.

“It’s not nice to fool mother nature!”