SPOTLIGHT

International reactions to China’s nuclear weapon: ‘A Bomb for all Asians and Africans’

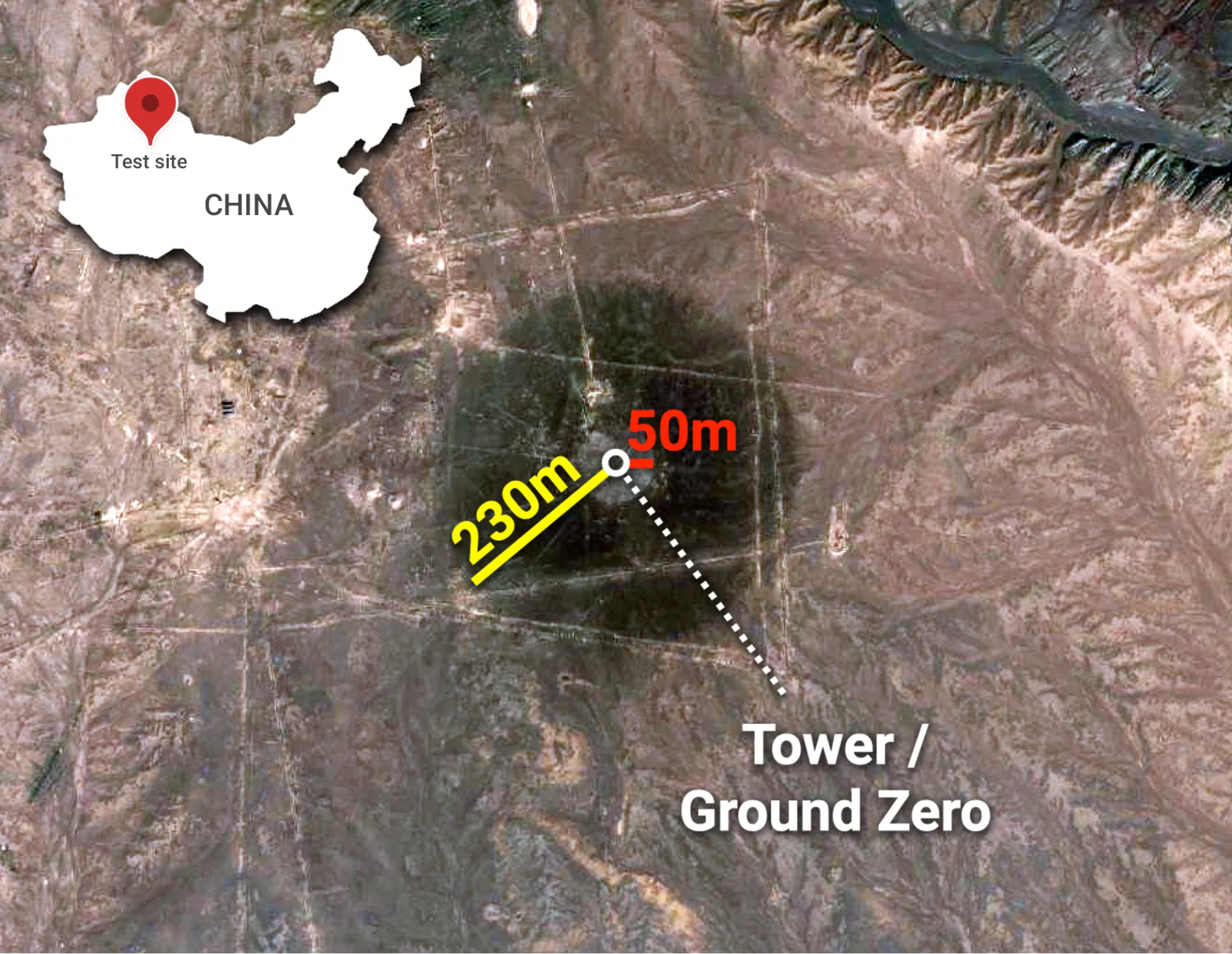

On the day China tested its first nuclear fission implosion device, the country’s Premier, Zhou Enlai, wrote a letter to foreign capitals, keen to minimise negative international diplomatic fallout to its test. Many in the United States feared a nuclear weapon proliferation cascade in the wake of China October 1964 test.

Taiwan, Japan, and India indeed openly criticized China’s testing. Beijing’s new nuclear weapon capability was considered a threat, and it likely reinforced demand for a continued US extended security guarantees in the region. Yet outright condemnation was the exception, not the rule. Instead, China’s nuclearization in the 1960s was, in most parts of the world, welcomed as a “bomb for all Asians and Africans.”

China’s nuclear weapons tests of the 1960s (there would be 10 in total) were interpreted by many developing countries as an equaliser, serving the interests of Communist powers and anti-colonial independence movements that had no nuclear deterrent of their own. When Zhou wrote his letter, it was mainly addressed to Asia and Africa, not Europe or the United States. Soon after, on October 30, 1964, another high-ranking Chinese official, Liu Shaoqi, declared that China’s bomb was a bomb that belonged to others. Liu could make this statement with some confidence as Beijing’s test was being welcomed by several states in Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Declassified archival documents within the Chinese Foreign Ministry show that these countries began to link Beijing’s scientific success to wider national liberation and international racial movements. China’s bomb was the first nuclear weapon to be possessed by a non-white, non-developed country.

The positive foreign state responses were recorded diligently within the Chinese Foreign Ministry. The Yemeni Ambassador Saleh Ali Al-Ashwal described the testing not simply as a victory for China, but also as an effort to safeguard international peace. In Indonesia, the racial element was explicitly pronounced, with a statement that now with China’s bomb, “not only white people can produce nuclear bombs.” In a cable, the Pakistani Foreign Ministry noted that: “Some said that this was the pride and glory of the Asians. Some said that we could talk to the United States on an equal footing now that we have the nuclear bomb and could speak on Pakistan’s behalf.” A message of the Ghanaian Ambassador to Algeria was also received, with the statement that “China’s atomic bomb belongs to all the Asian and African peoples.” In Cuba, the Chinese Embassy noted that Augusto Martinez Sanchez, the Cuban Minister of Labour, and Eulogio Cantillo, the chief of staff of the department of Protocol in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, apparently verbally congratulated China, with the latter stating: “[T]he Cuban ambassador said that China having atomic bombs is the same as us having atomic bombs”.

This outside validation and celebration of China’s nuclear testing is not well remembered today. Yet it remains ingrained in China’s own recollection of its nuclear past. It reinforces a goal China had with it nuclear weapons program from the start: to be seen as fundamentally different from other nuclear weapons states.

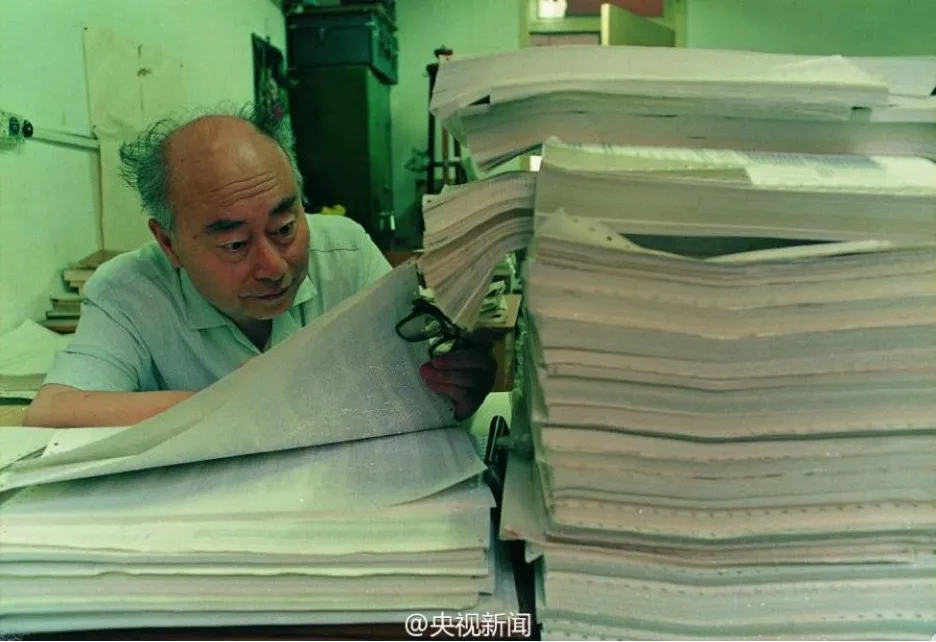

Nicola Leveringhaus is a senior lecturer with the Department of War Studies, King’s College London, United Kingdom. She is the author of China and Global Nuclear Order (Oxford University Press, 2015).

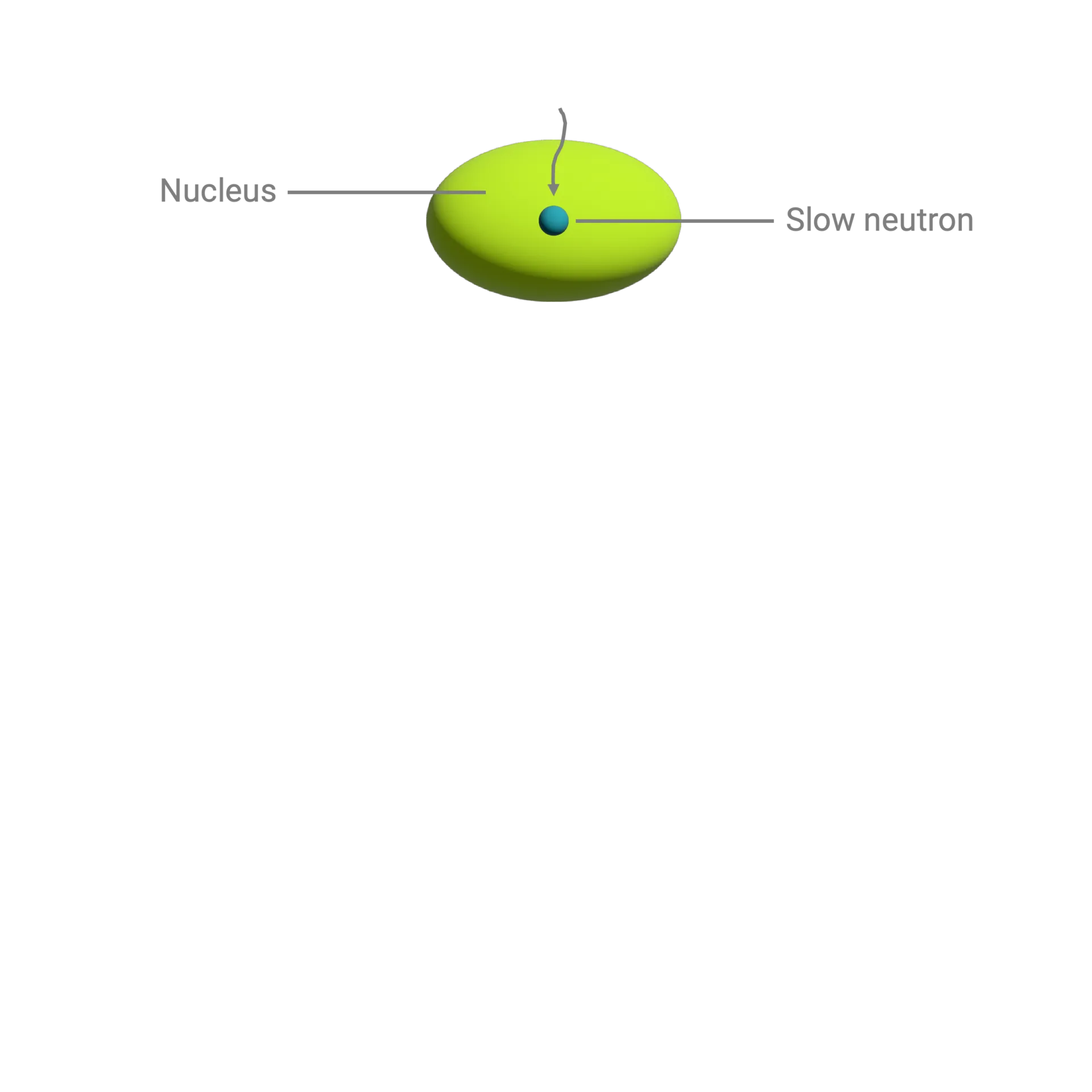

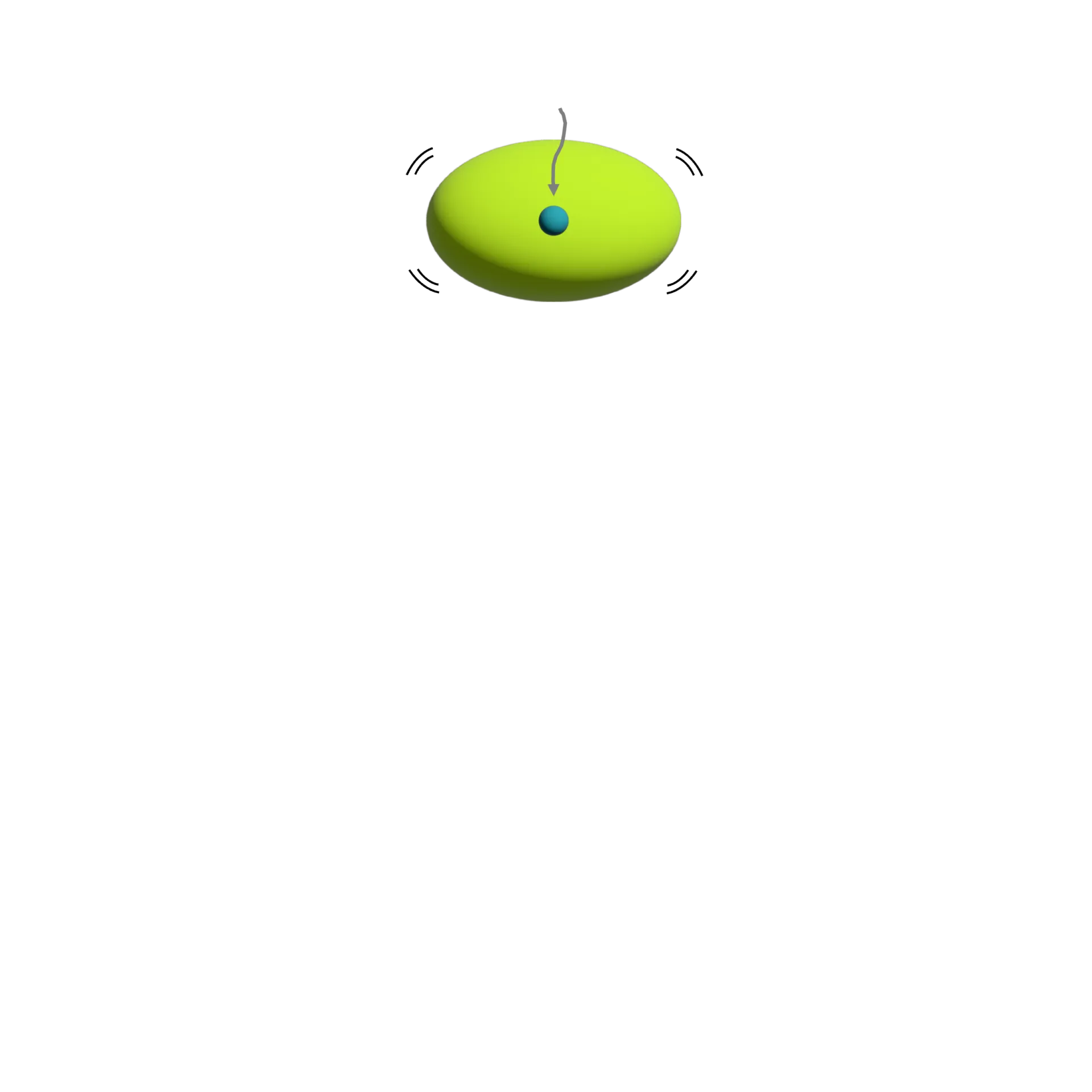

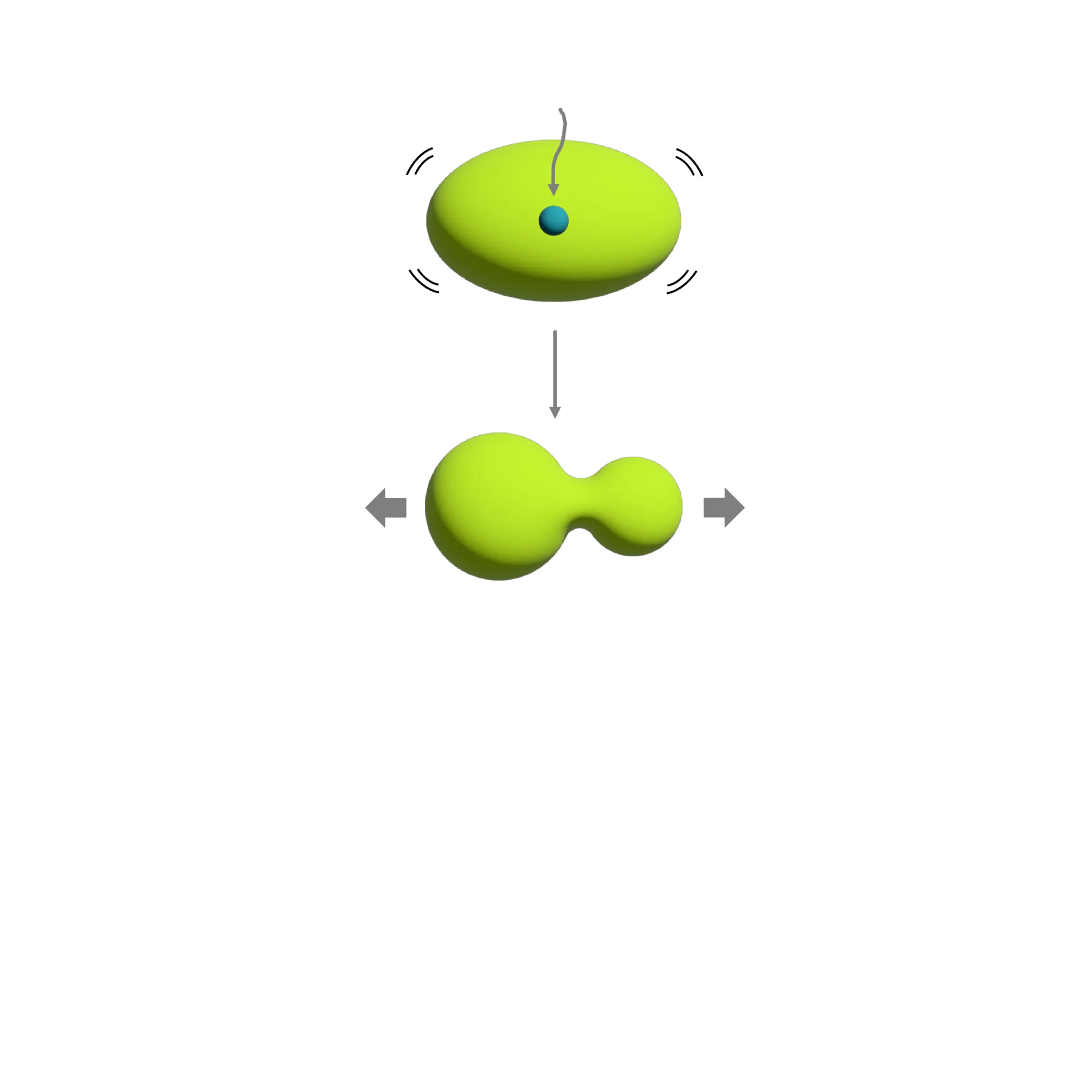

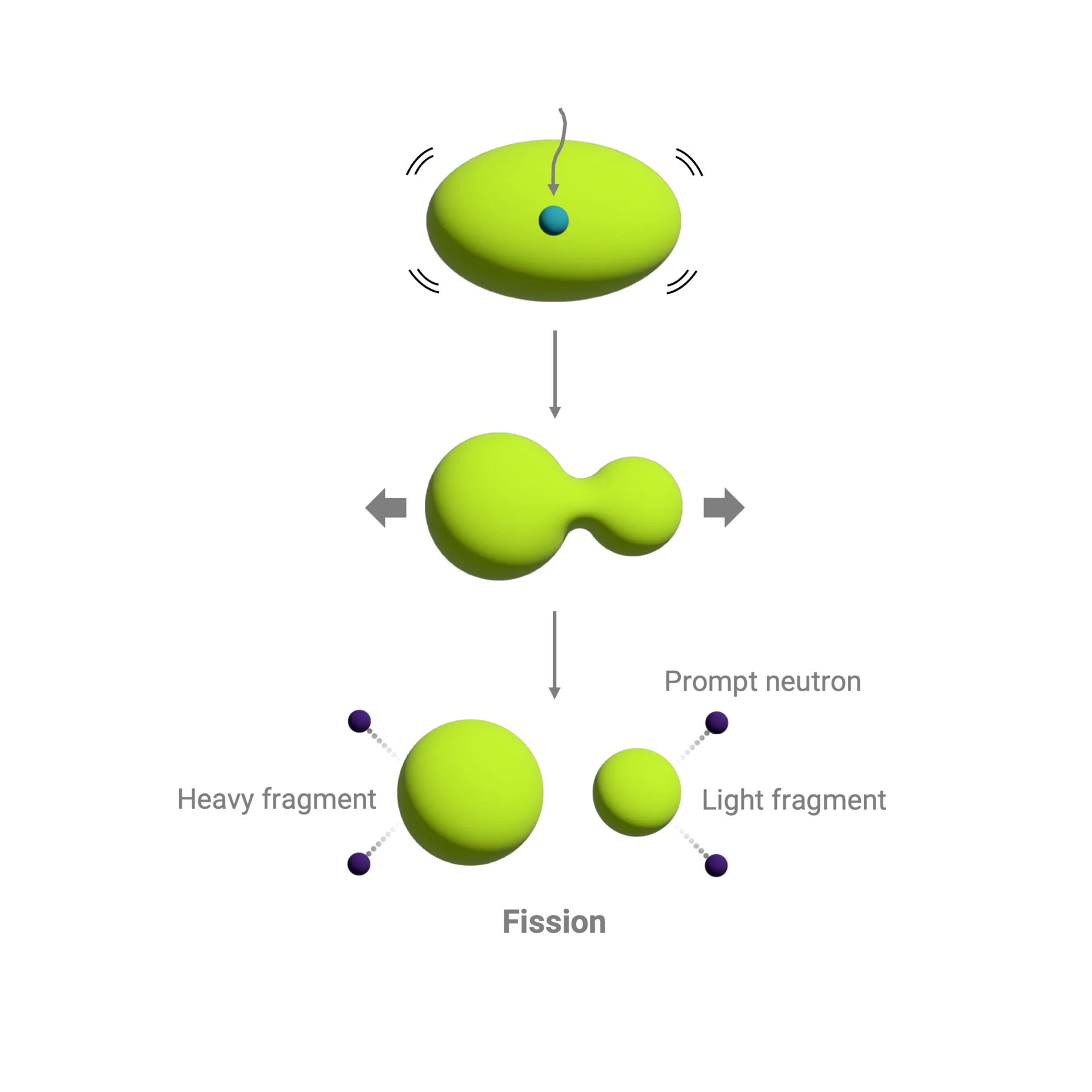

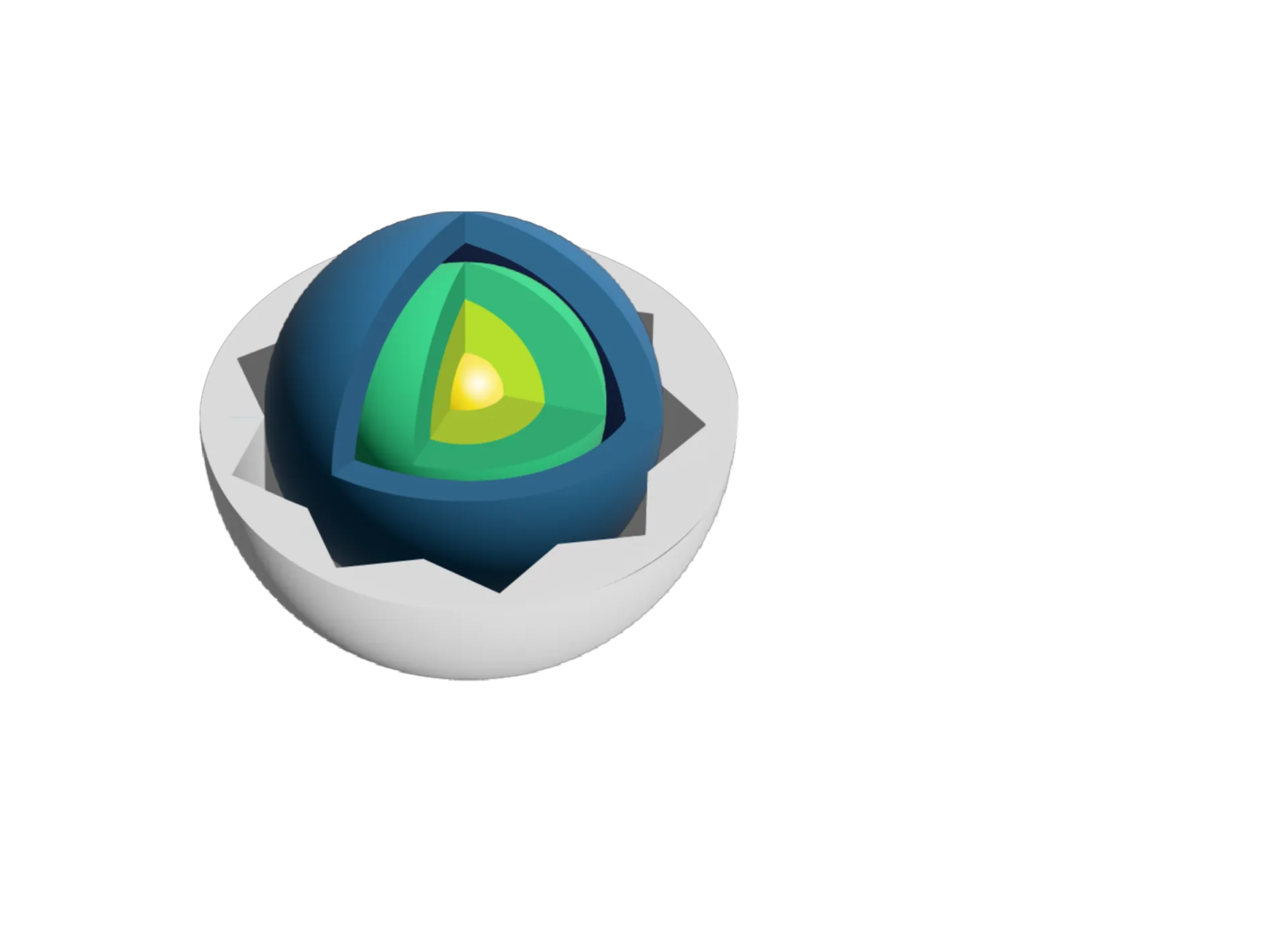

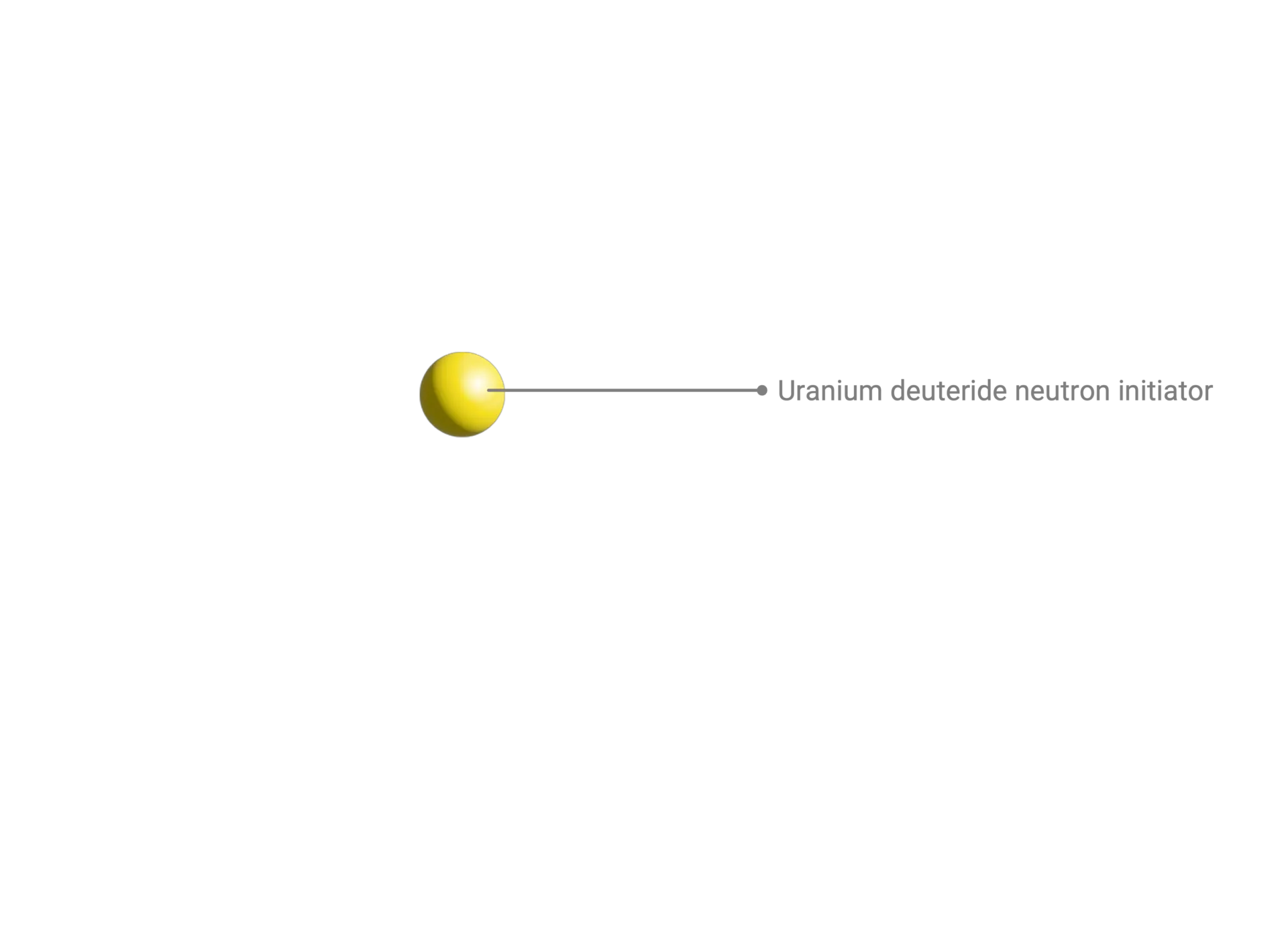

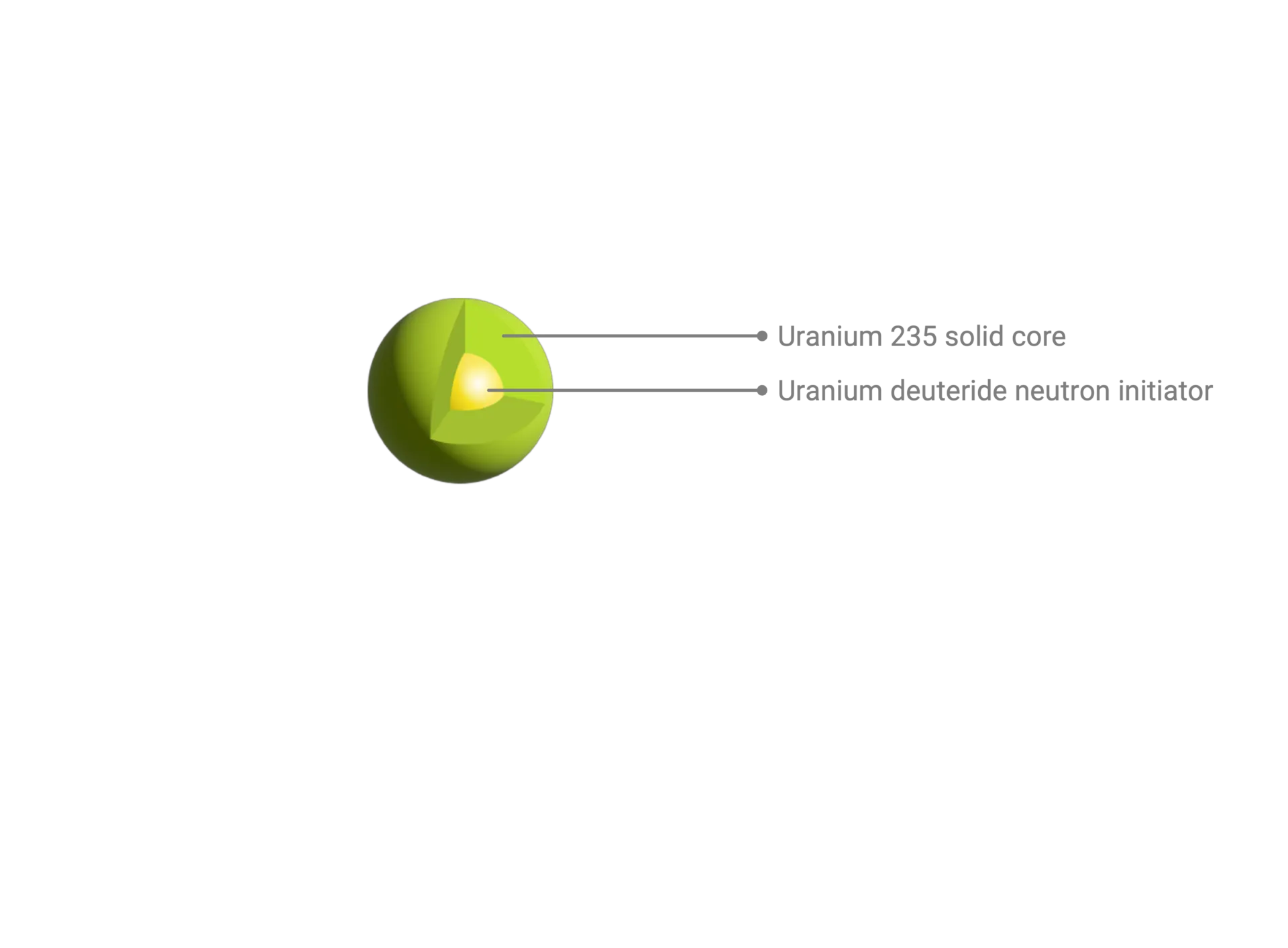

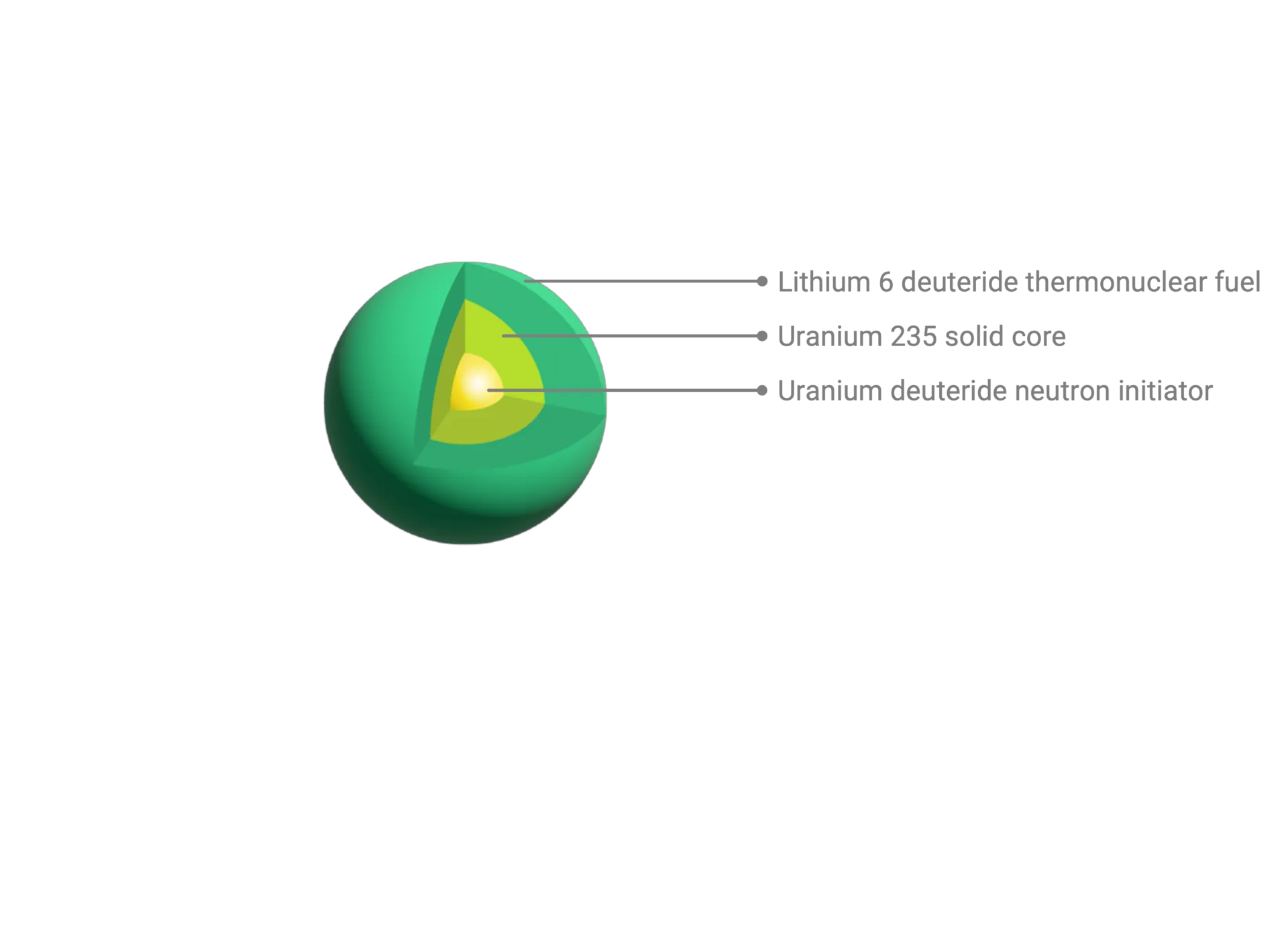

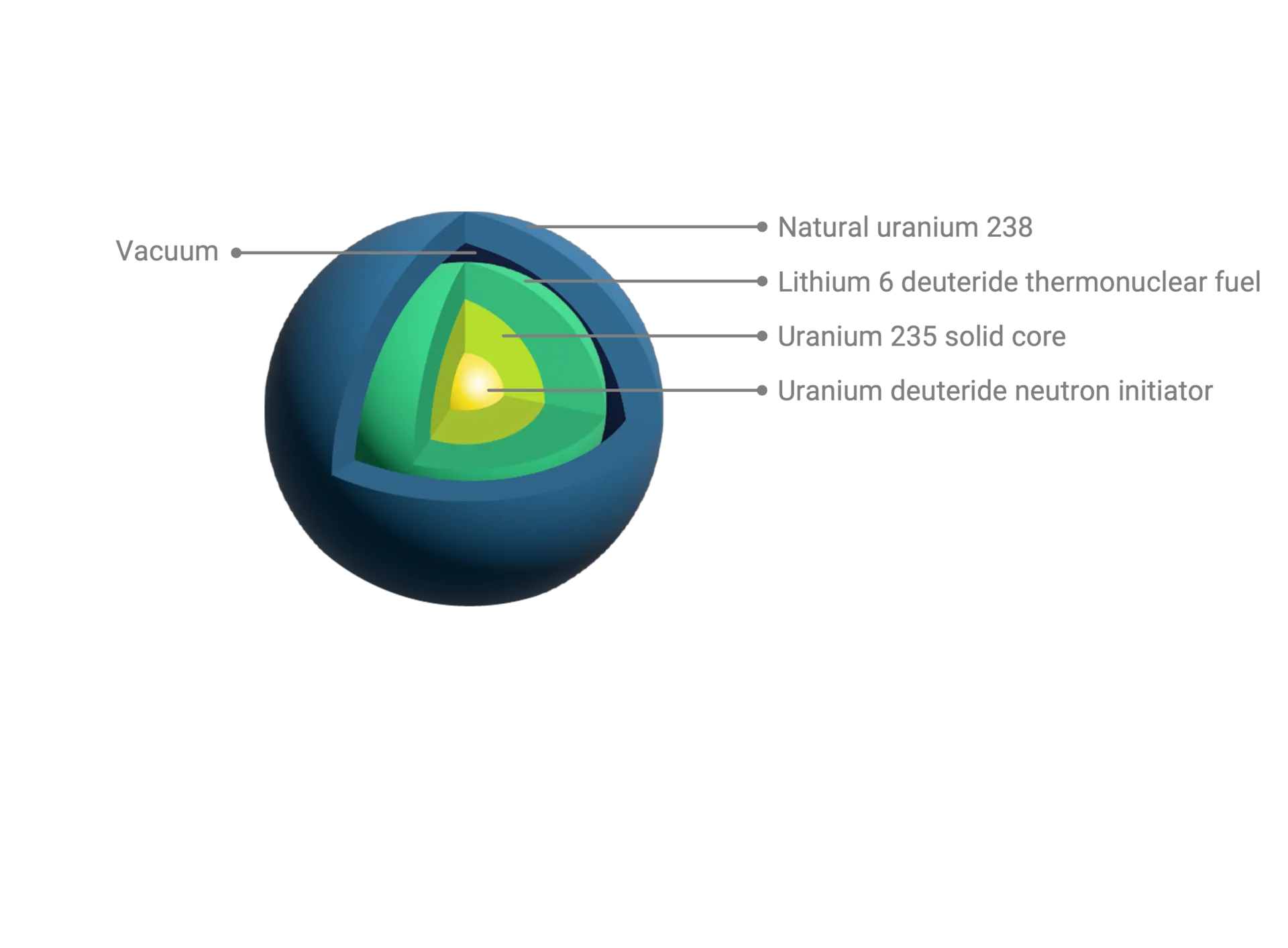

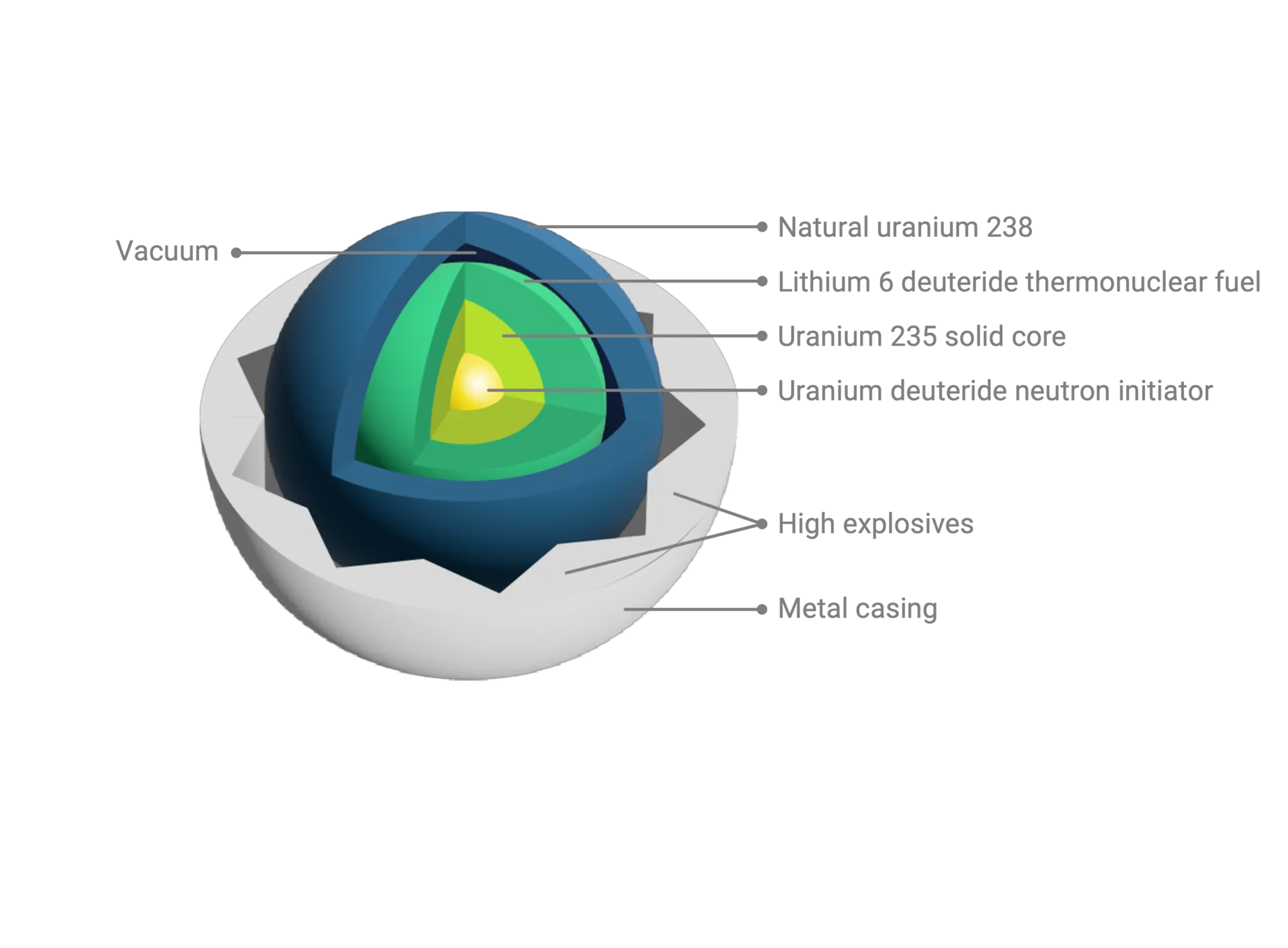

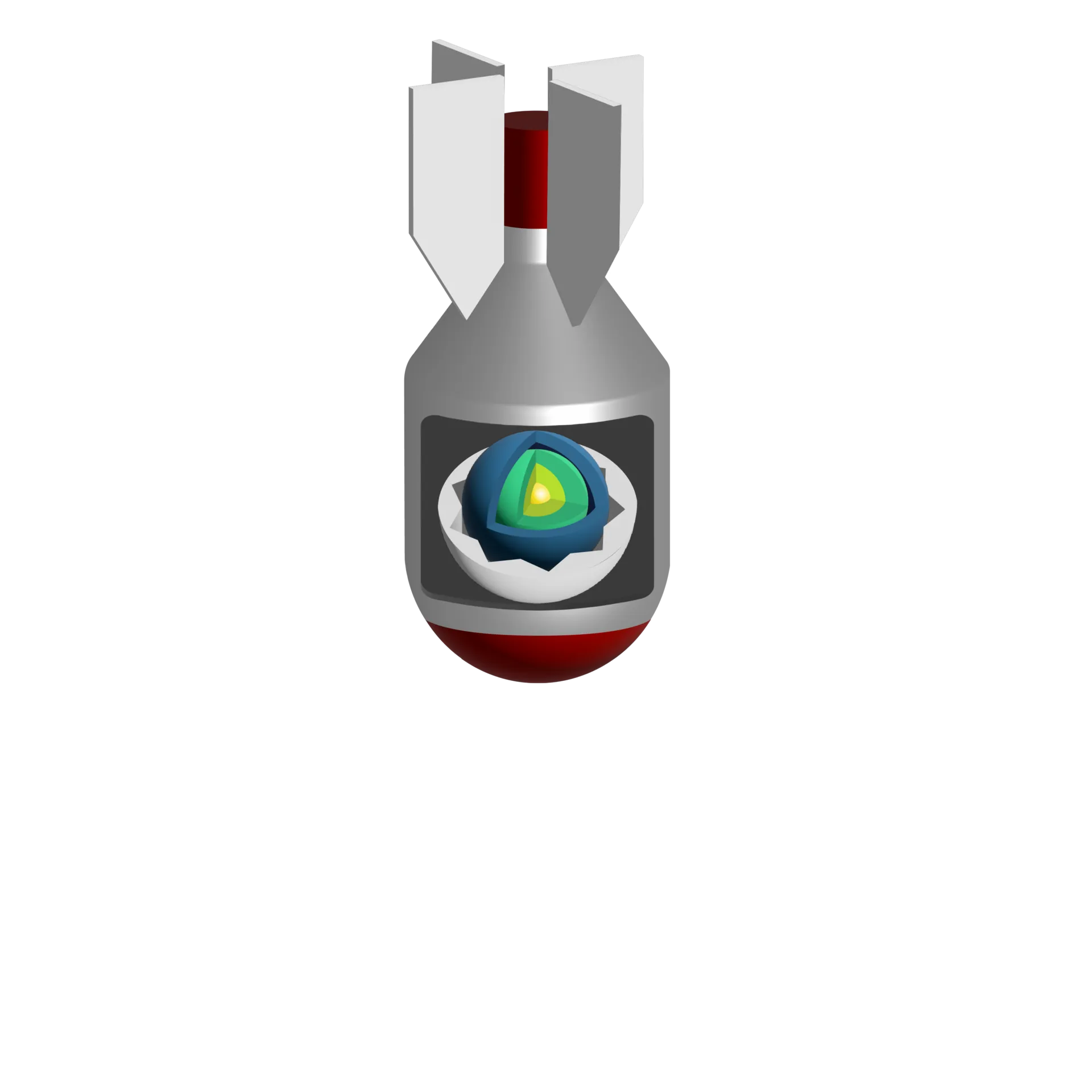

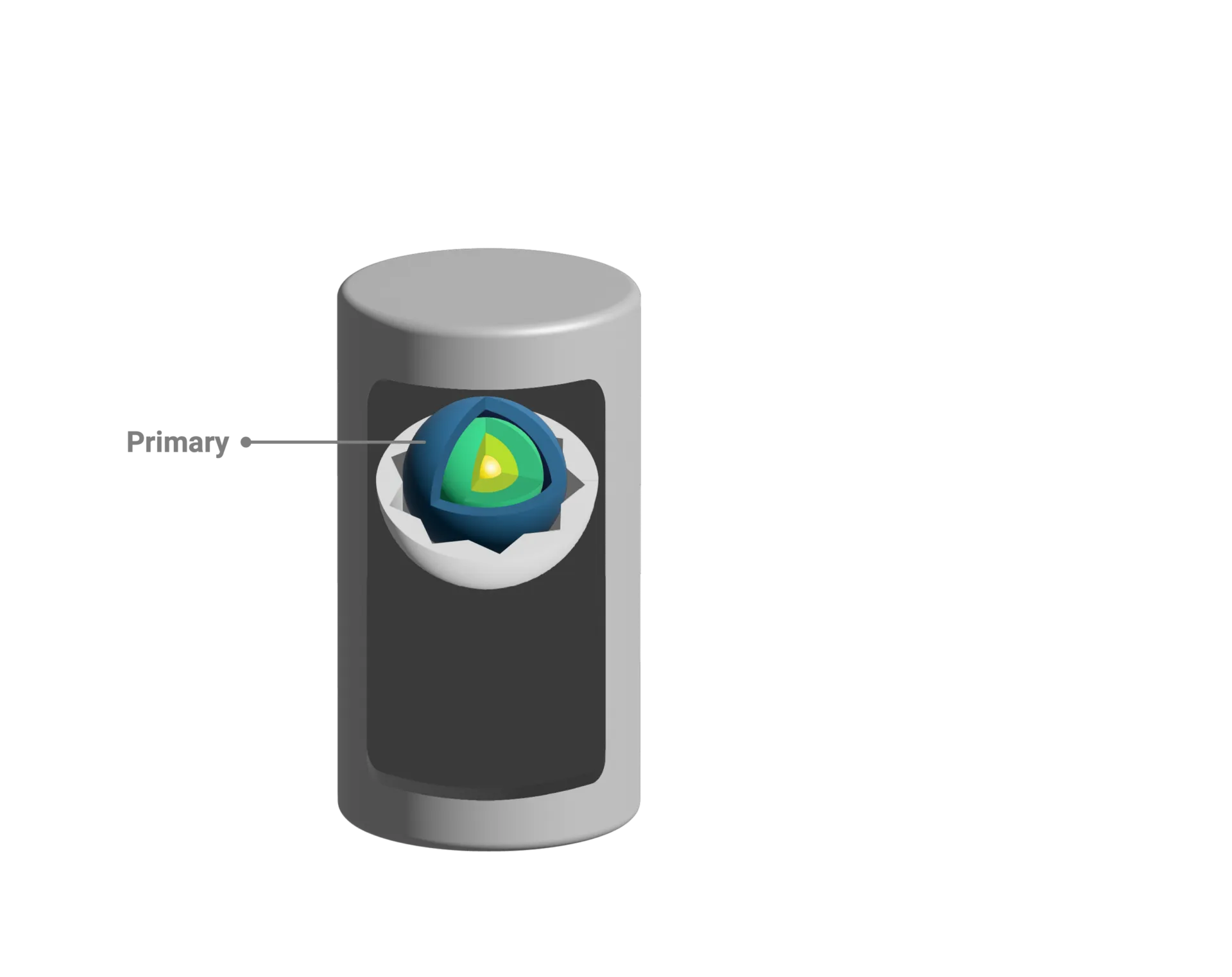

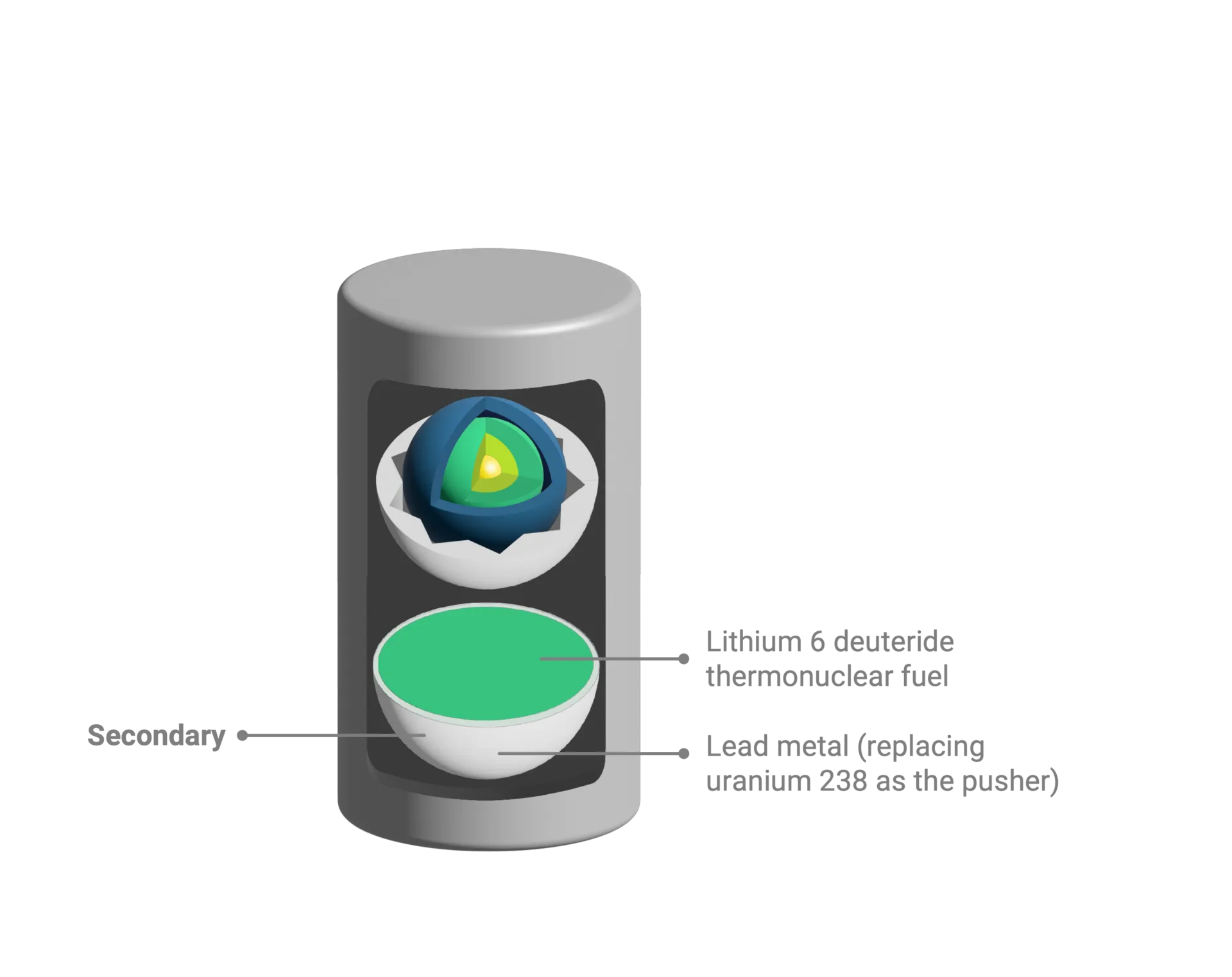

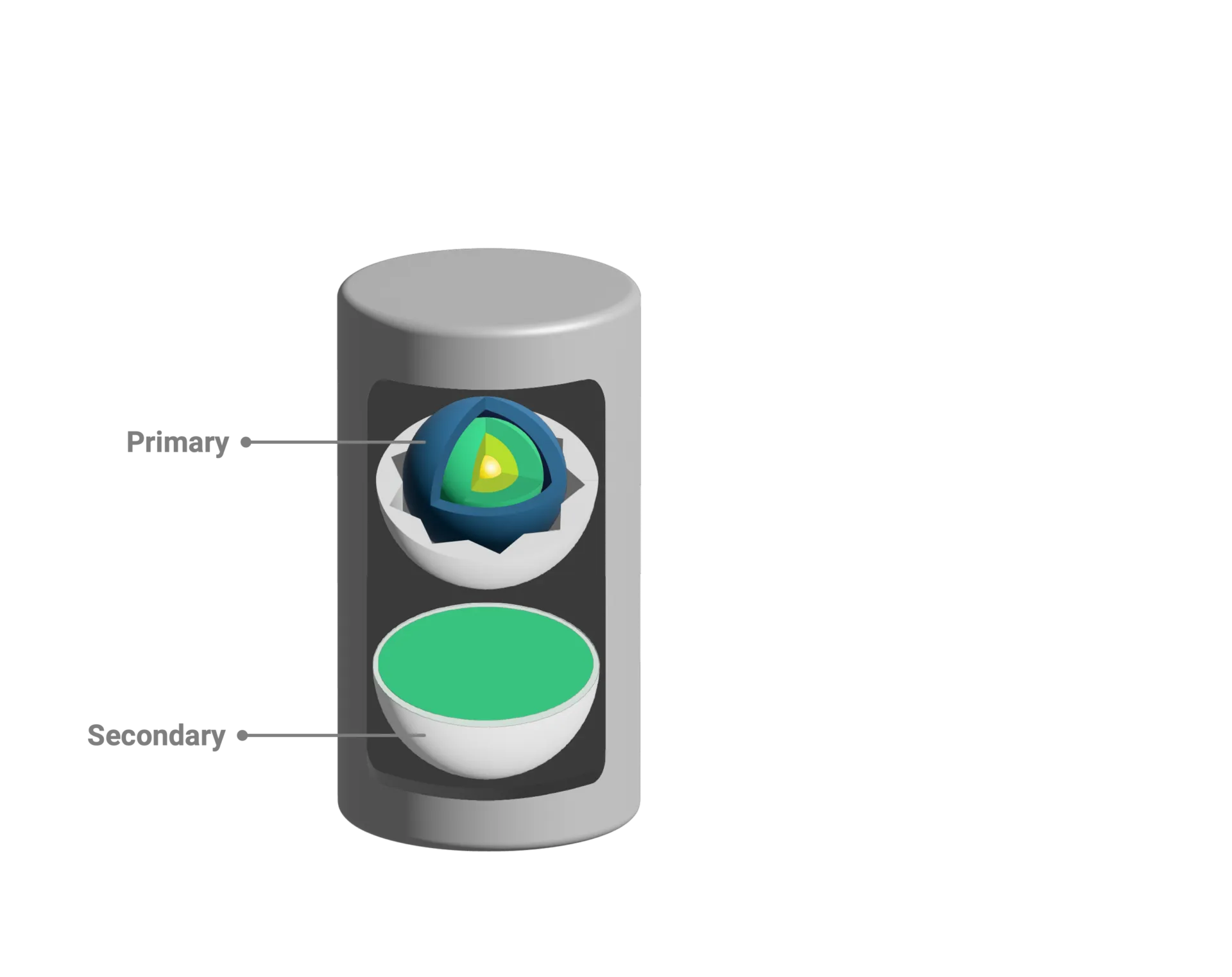

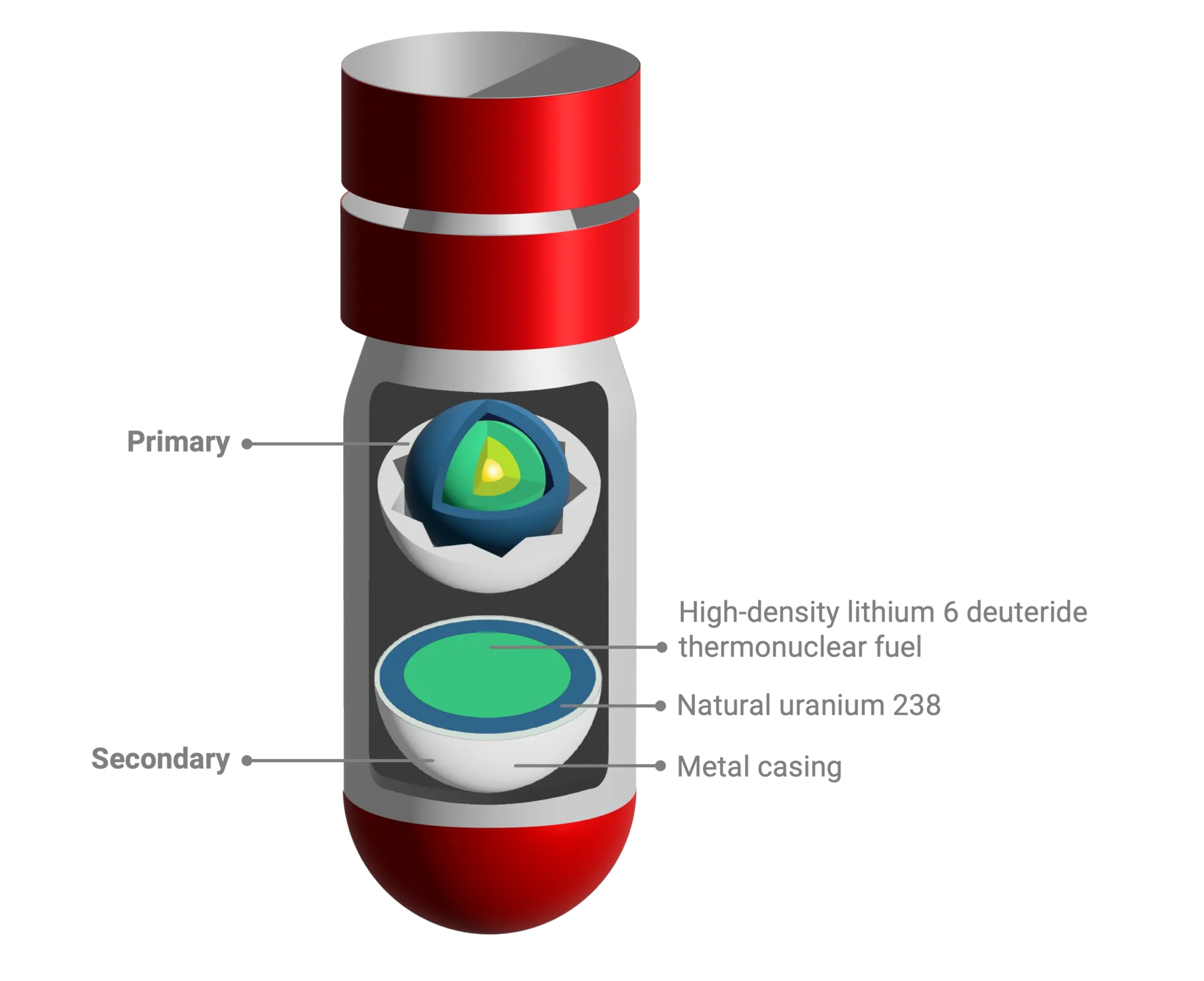

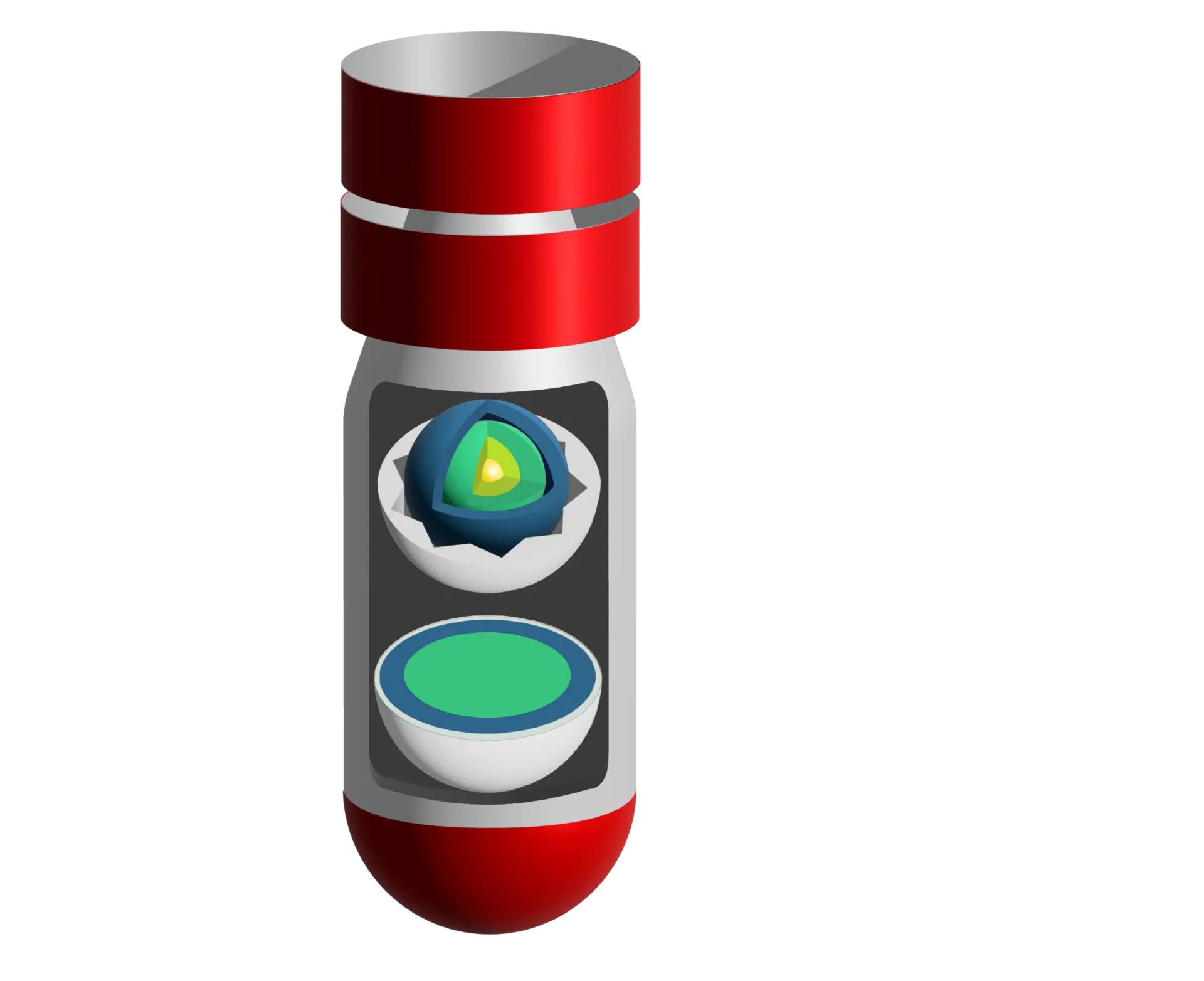

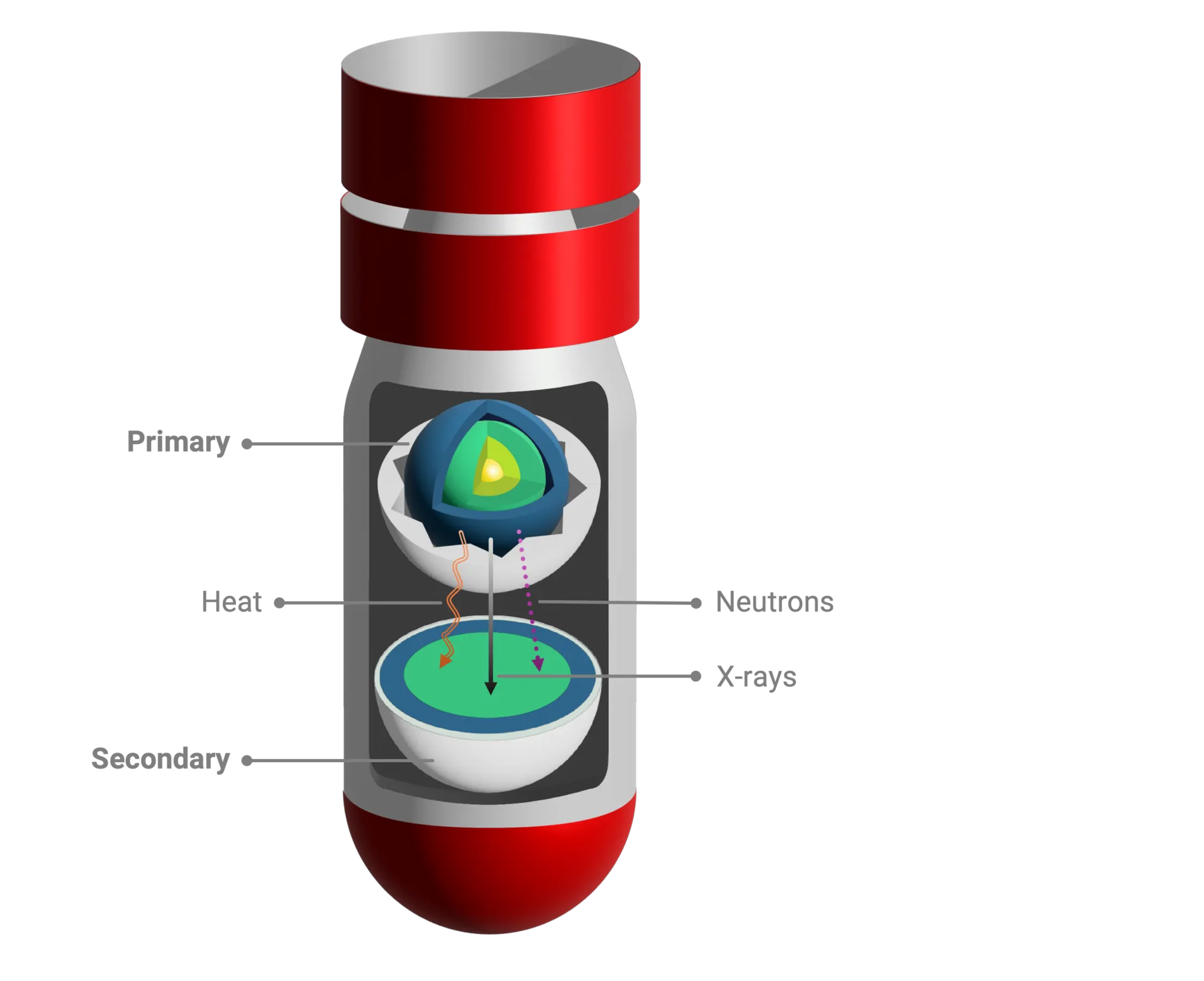

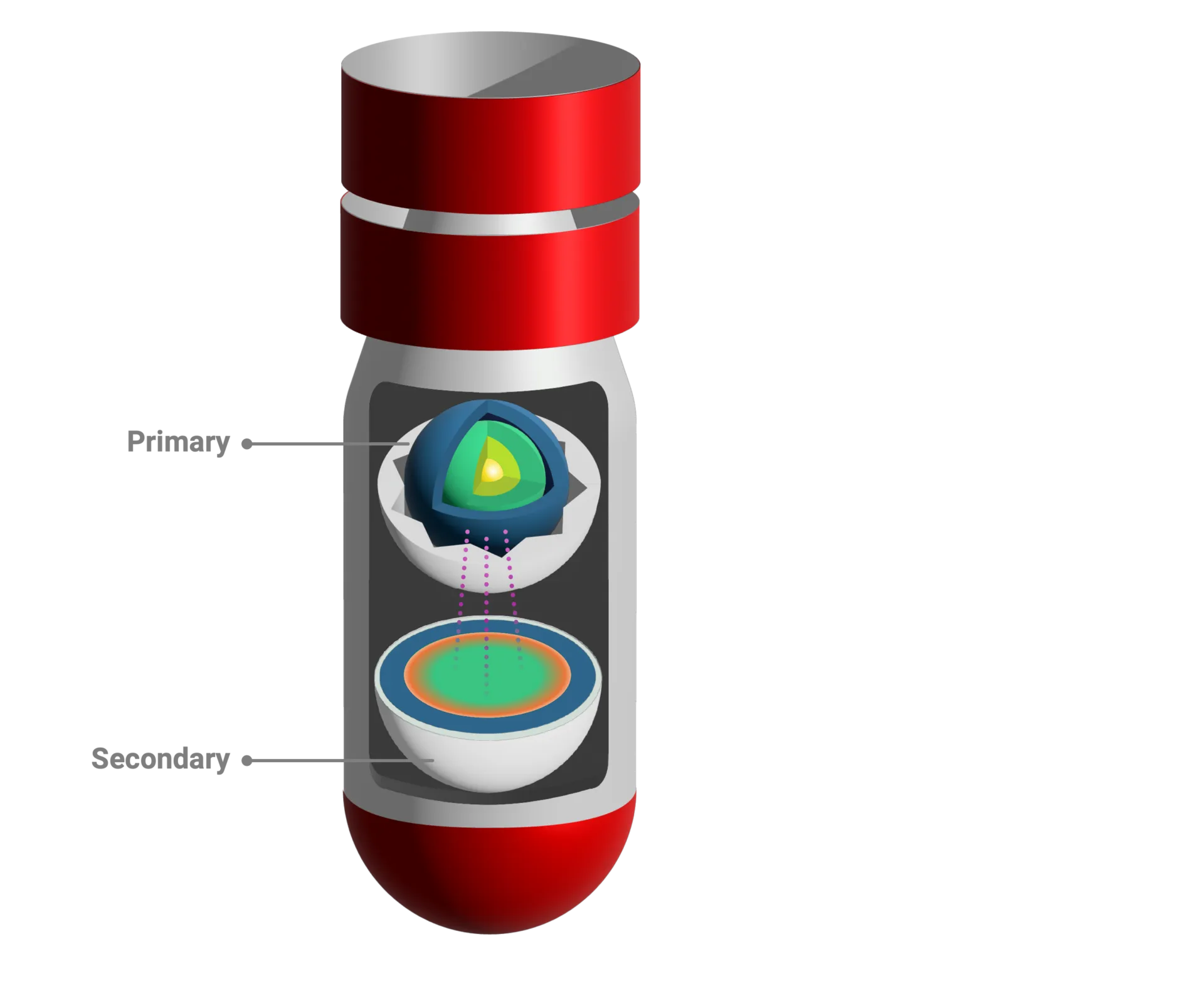

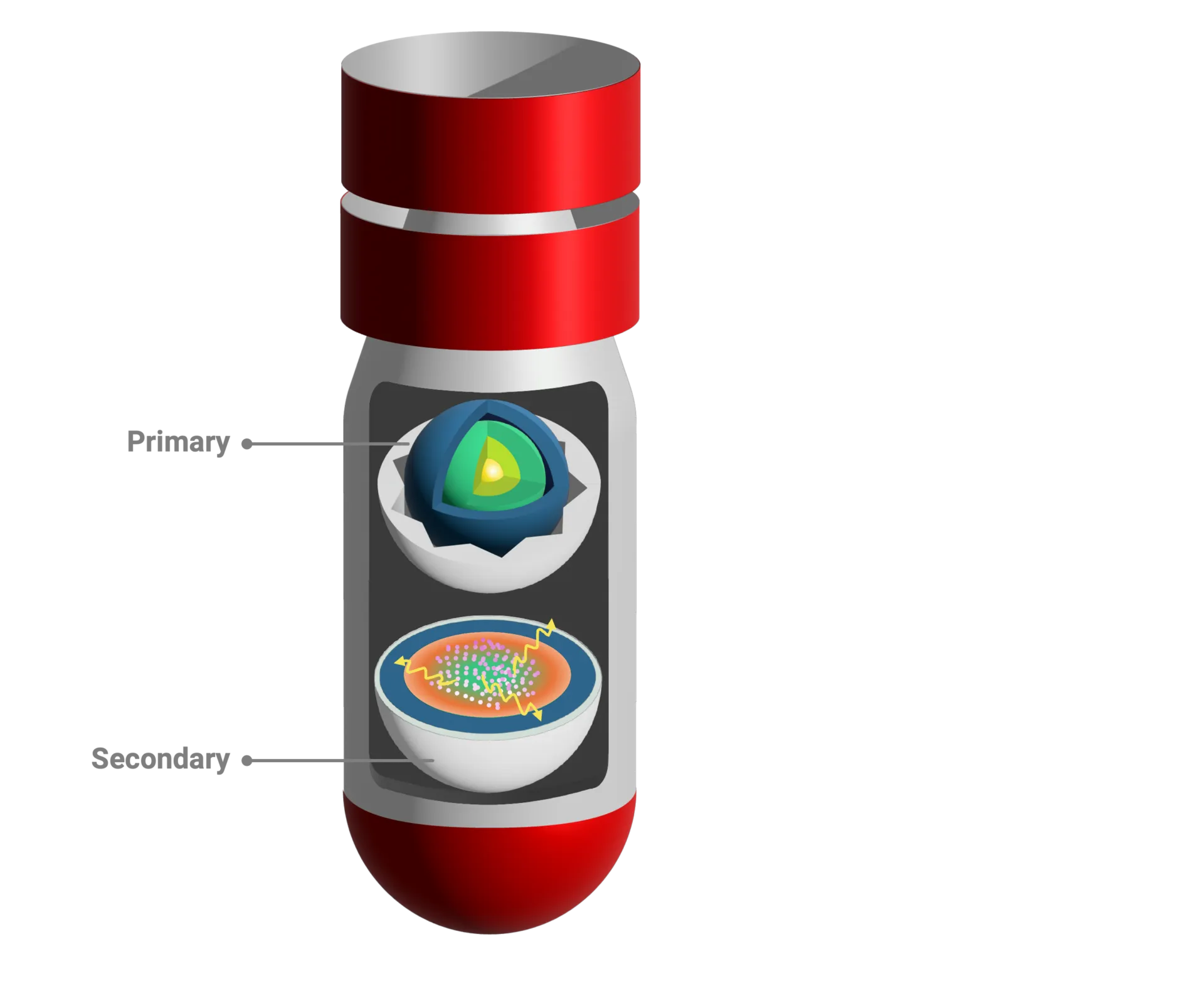

This is a well written, comprehensive article where one does not have to be a nuclear physicist or nuclear weapons scientist/engineer to understand it. The illustrations are fantastic. In my opinion, this is the best account of the Red Chinese thermonuclear weapons development I have read. I would like to see a book on this subject published by Hui Zhang.