MARS ATTACKS:

How Elon Musk's plans for Mars threaten Earth

By Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith

Illustrations by Zach Weinersmith with select images courtesy of Penguin Press

Layout by Erik English

March 20, 2025

The world is nearly all parcelled out,

and what there is left of it is being

divided up, conquered, and colonised.

To think of these stars that you see overhead at night,

these vast worlds which we can never reach.

I would annex the planets if I could; I often think of that.

It makes me sad to see them so clear and yet so far.

-Cecil Rhodes

Elon Musk, the world’s richest man and CEO of SpaceX and Tesla, is intent on creating a one-million-person colony on Mars. As the head of the Department of Government Efficiency, Musk also seems content to break anything that stands in his way—including potentially a Cold War era treaty that has kept humanity safe for over 50 years, the Outer Space Treaty (OST). Musk’s rejection of international governance could have lasting implications for life on earth, and could augur a new era of geopolitical conflict.

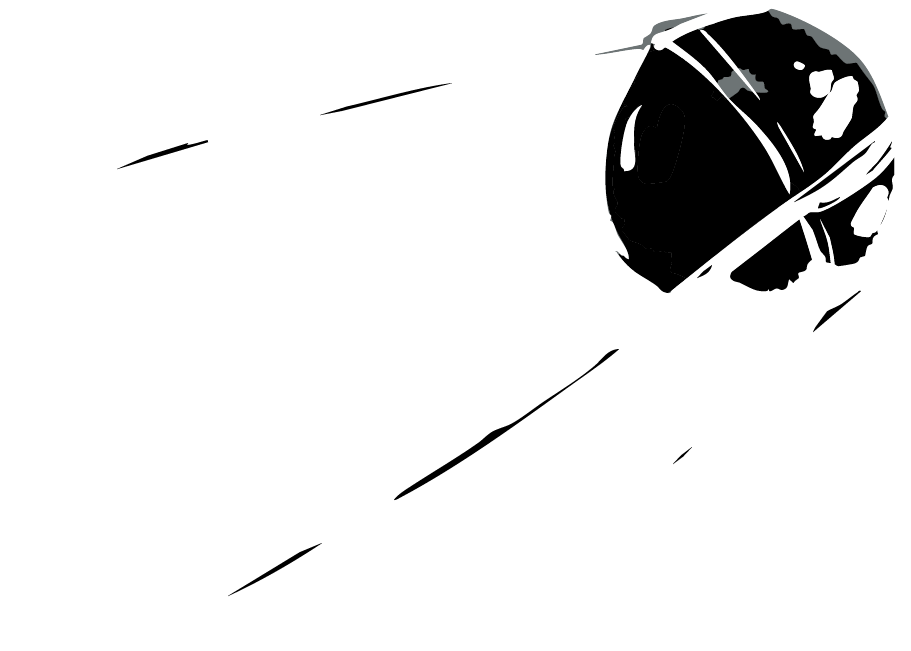

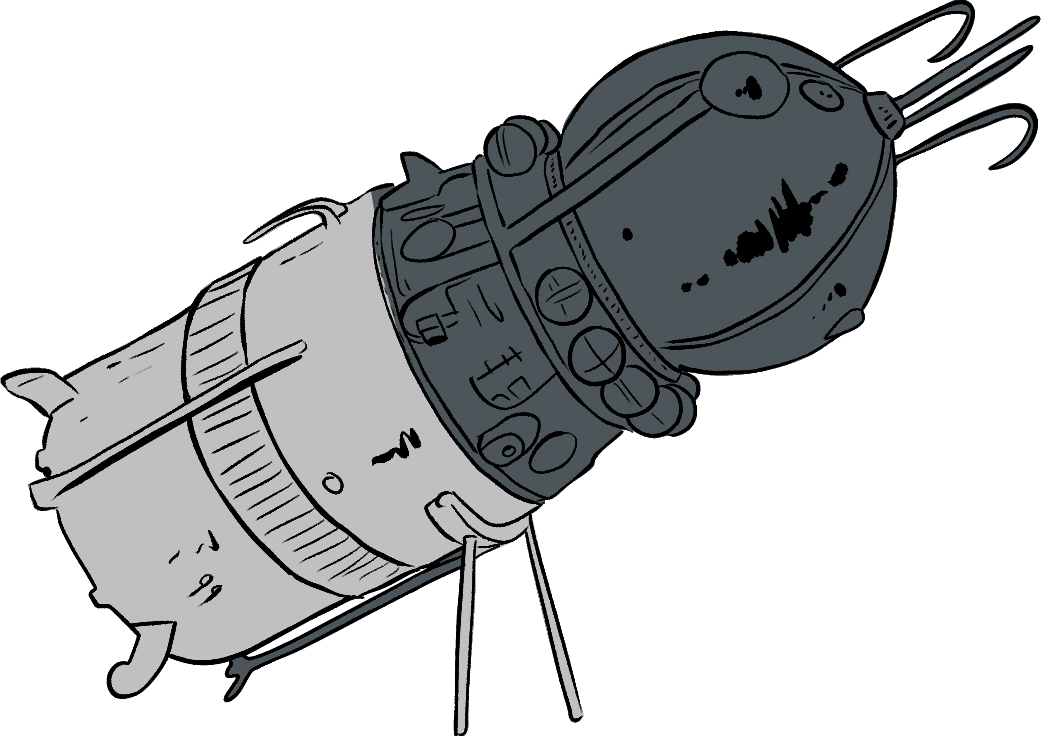

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik-1, ushering in the age of spacefaring as geopolitics.

Just a decade later the two sides of the Cold War joined the international community to ratify the main international treaty that still governs space today: The 1967 United Nations Outer Space Treaty. How were nations able to come together and create a regulatory framework for lands none of them had yet visited?

Fear likely helped.

The first thing to fear was being the loser in human expansion beyond Earth. On April 12, 1961, Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to go to space.

Less than a month after that, the US sent Alan Shephard to space. While the Soviets beat the US in many of the human space firsts, the Americans were close behind, catching up quickly, and no one could be certain who would win Kennedy’s newly-declared race to the moon.

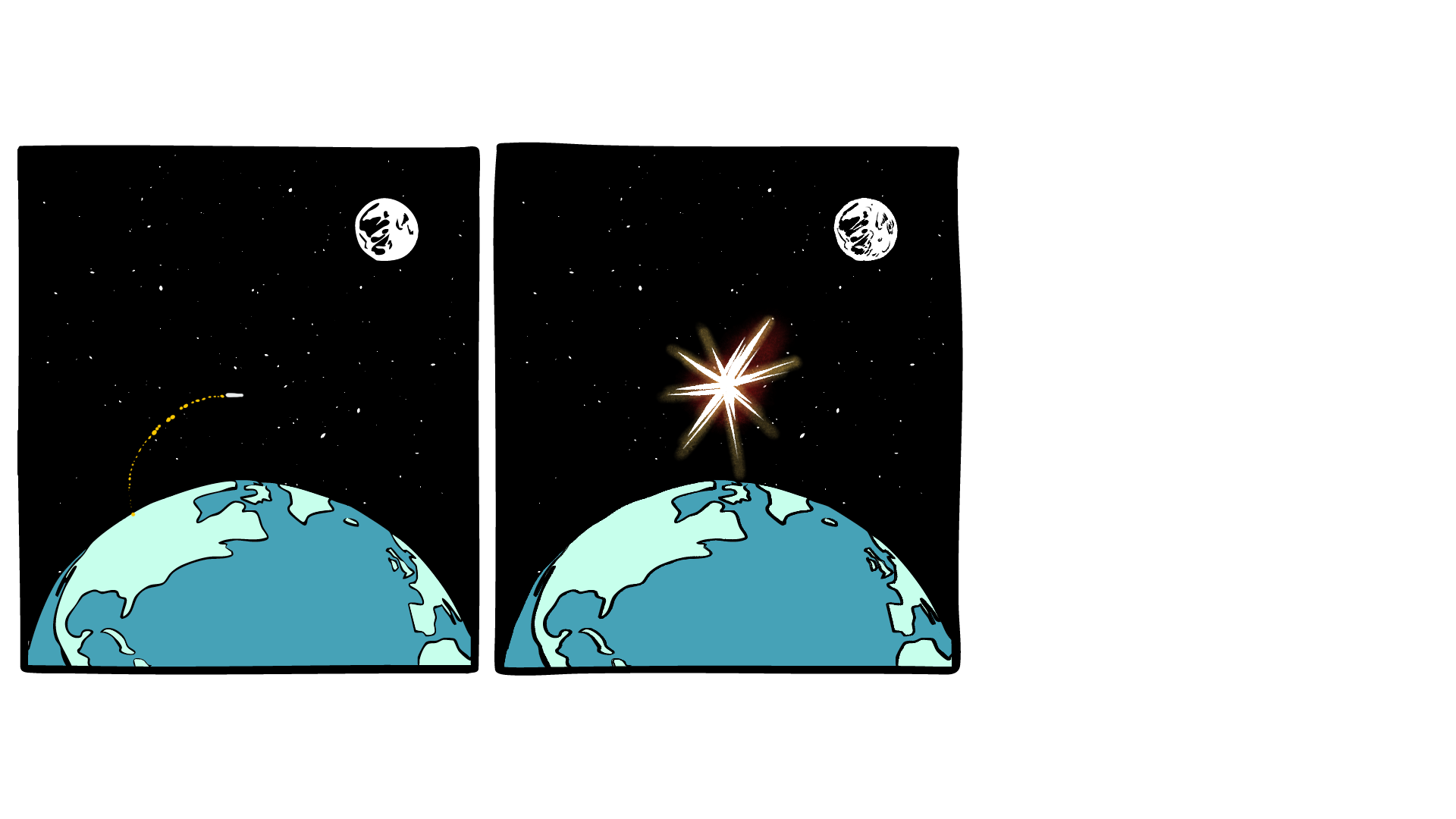

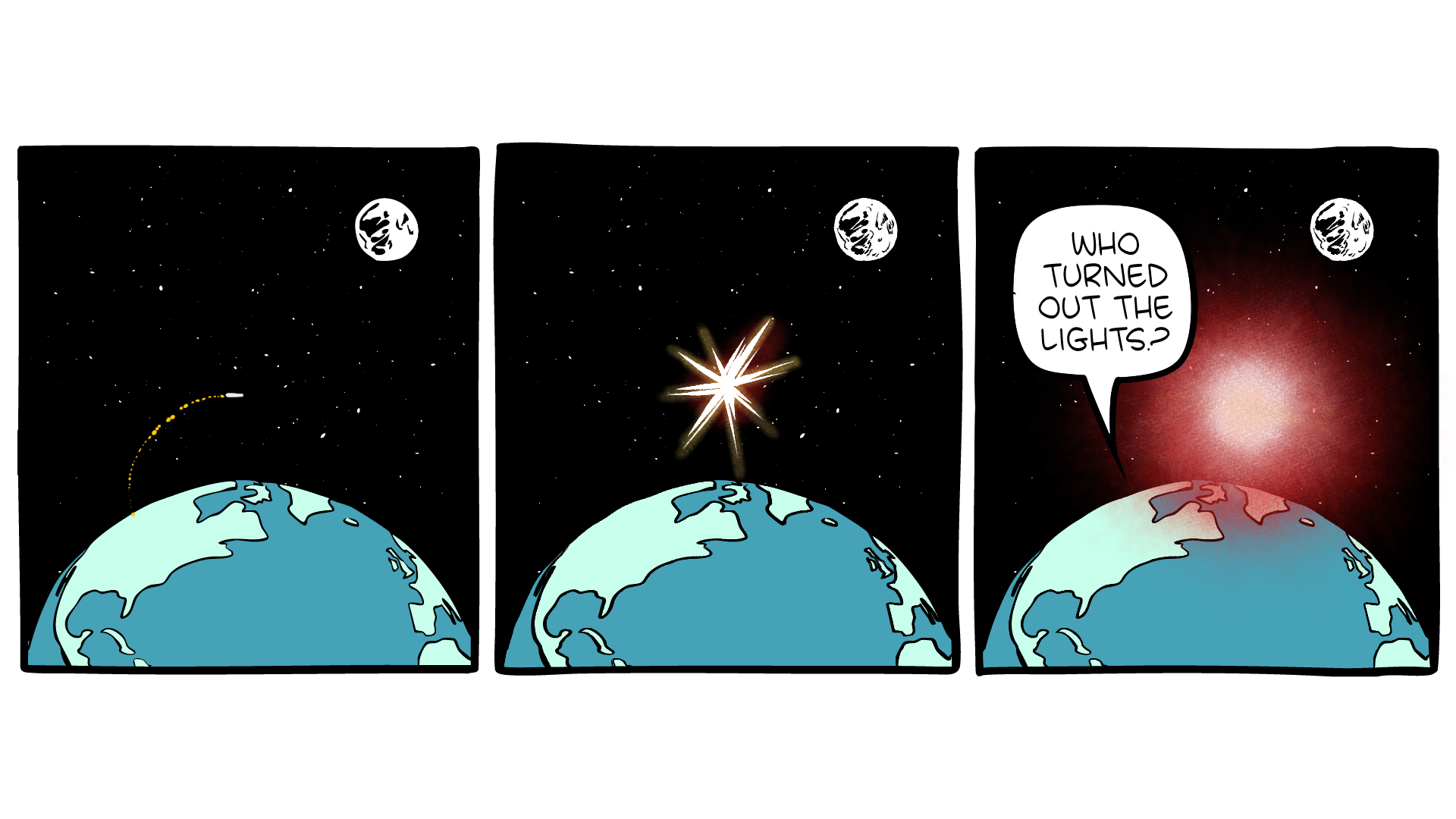

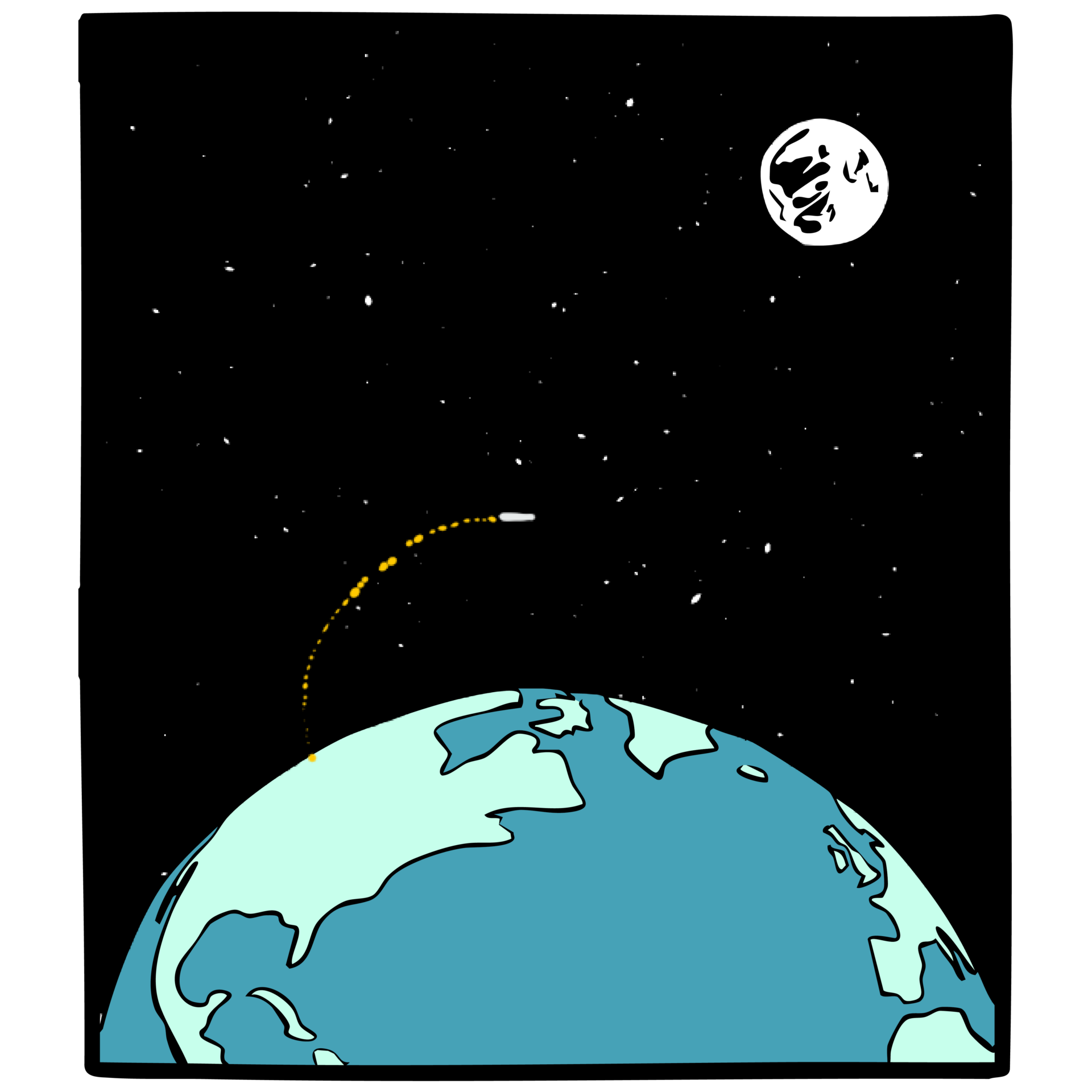

Now largely forgotten by the public was the escalating threat of space-weaponization.

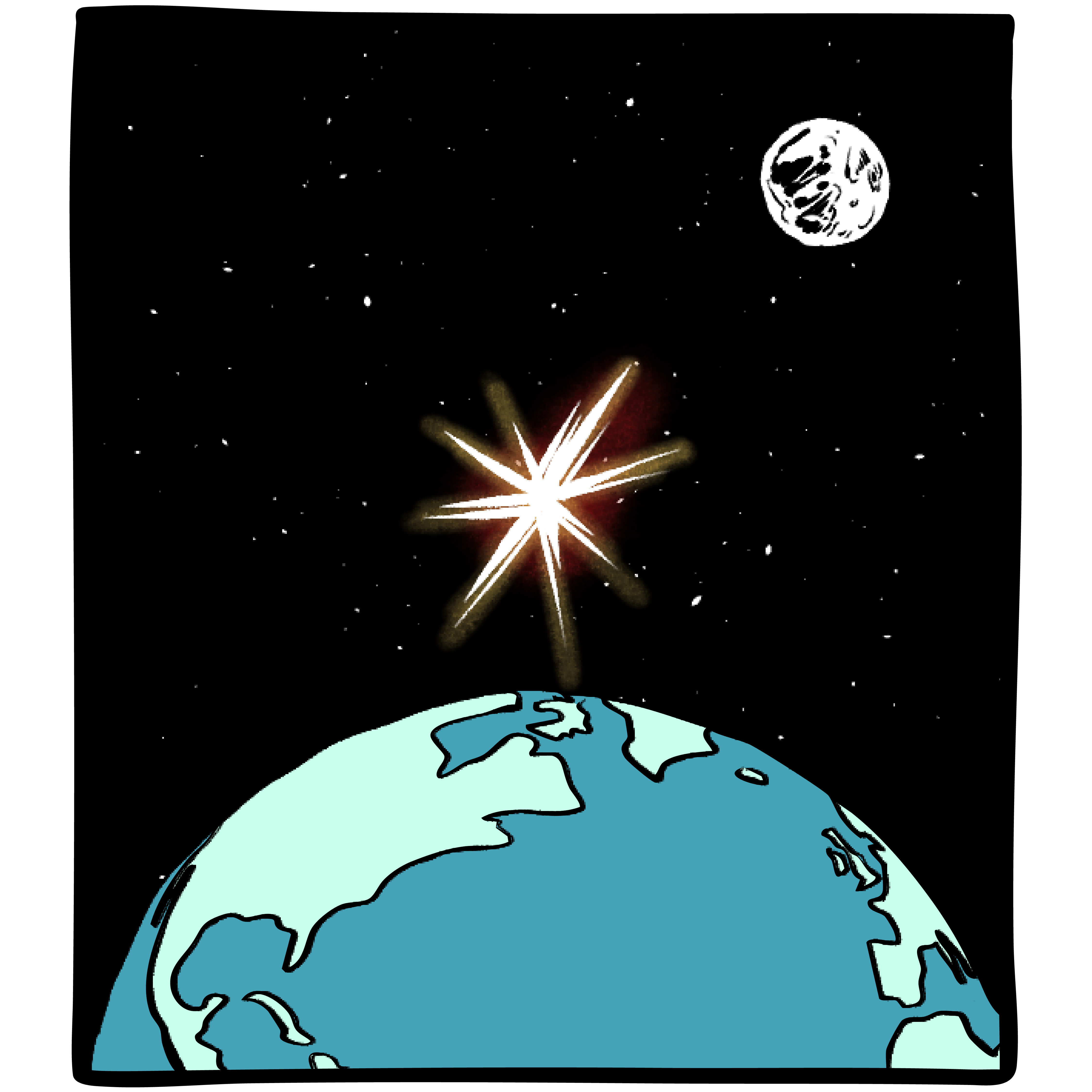

On July 9, 1962, the United States lit up the sky with a 1.4 megaton H-Bomb detonated 400 kilometers high as part of a project called “Starfish Prime.”

Radio transmissions and phone calls were disrupted, streetlights thousands of miles away in Hawaii flickered out, airplanes experienced electrical surges, and six satellites were damaged.

Now largely forgotten by the public was the escalating threat of space-weaponization.

On July 9, 1962, the United States lit up the sky with a 1.4 megaton H-Bomb detonated 400 kilometers high as part of a project called “Starfish Prime.”

Radio transmissions and phone calls were disrupted, streetlights thousands of miles away in Hawaii flickered out, airplanes experienced electrical surges, and six satellites were damaged.

The USSR conducted similar tests, which at one point knocked out parts of Kazakhstan’s electrical grid. None of this was forbidden by international law at the time.

So, just five years after the first satellite, the two most powerful nations on the planet find themselves in a terrifying new type of arms race that would’ve been unimaginable a generation earlier, and neither is certain who has the upper hand.

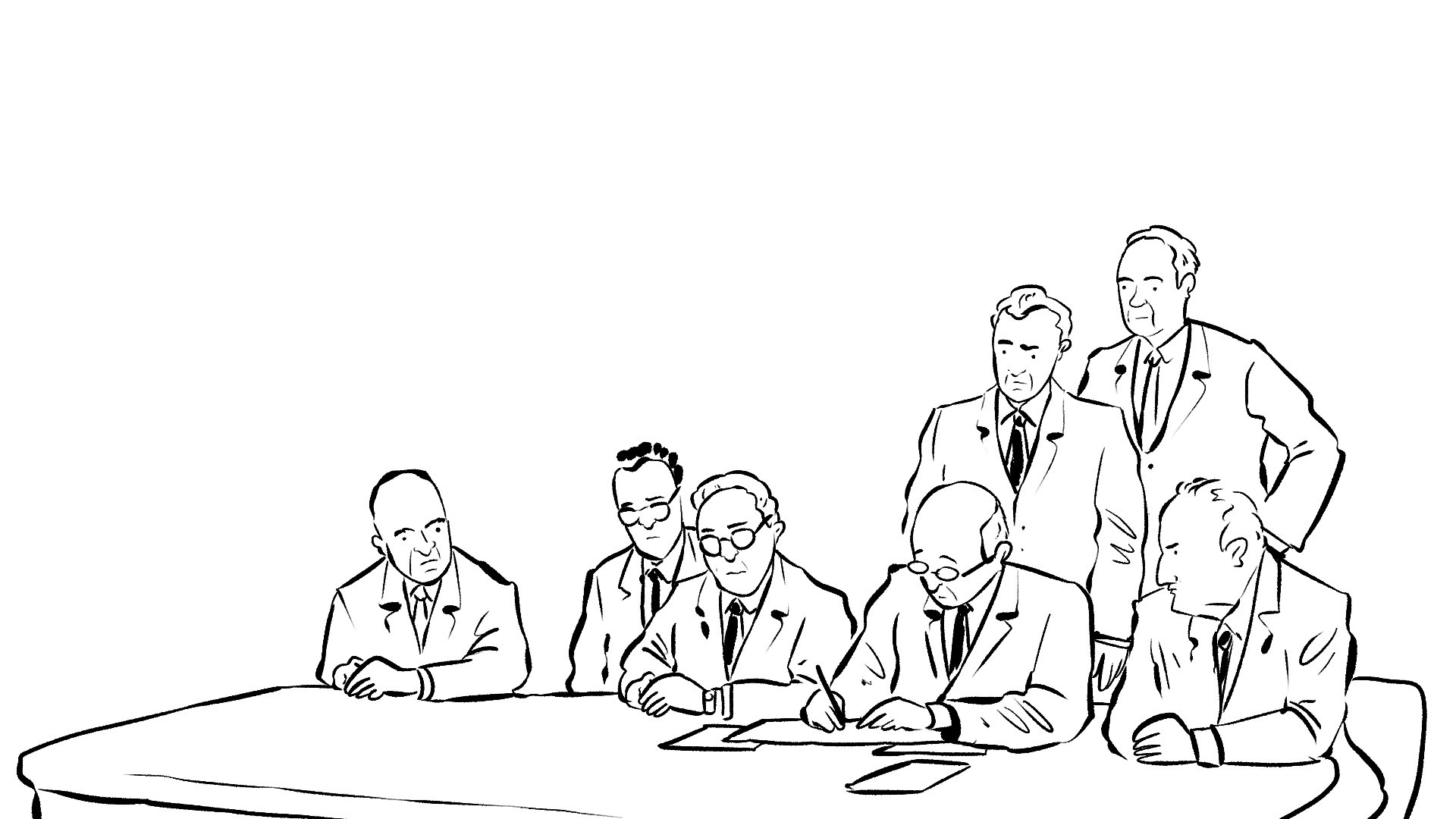

Faced with this fearful reality, leaders and diplomats did something that seems to be ever more difficult today: they cooperated.

Cooperation began with the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which ended high altitude nuclear testing.

The same year, the United Nations declared a set of principles for space, which would ultimately become the 1967 United Nations Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, otherwise known as the Outer Space Treaty or OST.

Along with three smaller treaties ratified during the next eight years, OST remains the rules of the road for space over 50 years later.

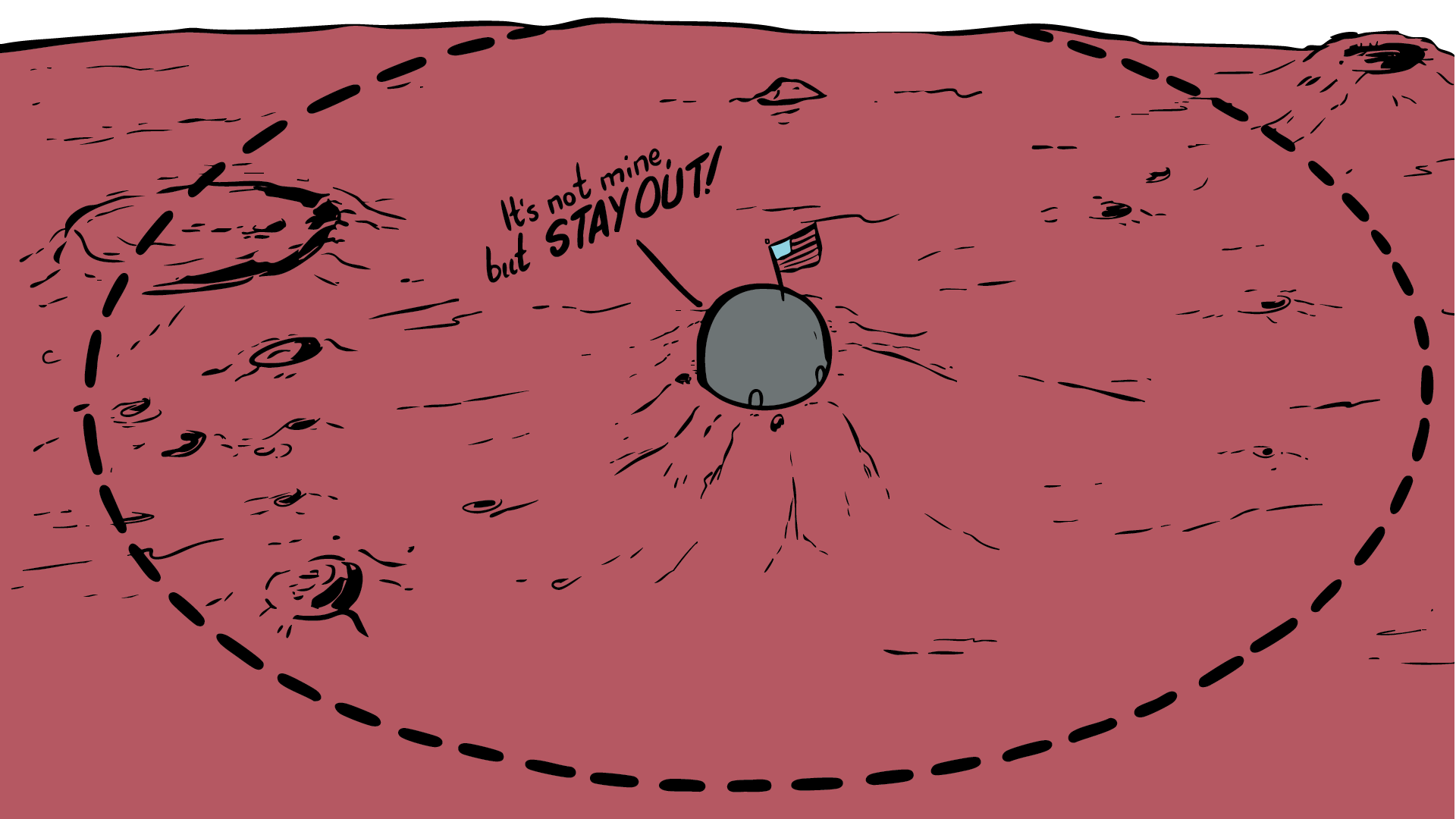

Put simply, the treaties require good behavior in space: no claims of sovereign territory, no weapons of mass destruction in space, and if you cause harm with a space object, you’re obligated to make the harmed party whole.

Many enthusiasts for space expansion believe the Outer Space Treaty has impeded humanity’s flourishing, by limiting the growth of a dynamic capitalist space-economy. In our conversations with them, they frequently hope for, or expect, these documents will be torn up. This is possible, but may imply more than you think.

There are differences between these systems, of course. Notably, Antarctic law bans resource exploitation, sea law regulates it, while the emerging consensus is that space law allows resource exploitation by anyone, provided they don’t claim sovereignty over the land where the extraction is occuring.

But, the throughline is that all are commons. In every instance after World War II, where technology opened up a vast new territory to humanity, we chose to stop land claims, and to prioritize peace, research, and environmental preservation. These different treaty systems don’t exist in isolation. A new precedent in what nations can do in the commons of space could impact what nations can do in the commons of Earth.

Undoing space law, then, could affect more than would be Martian homesteaders—it could alter the regulatory structure for roughly half of Earth’s surface.

International law doesn’t always have a lot of fans, and we won’t defend its every hypocrisy and failure. What we will say is that under the post-WWII system, our world has gotten richer, less colonial, and in a feat that would have surprised anyone in 1945, has never since Hiroshima and Nagasaki witnessed the use of nuclear weapons in warfare.

Boring? Maybe, but then your roof is boring until there’s a hole in it.

Our concern today is that SpaceX’s CEO, Elon Musk, has big plans for space - and those plans are not all consistent with the OST.

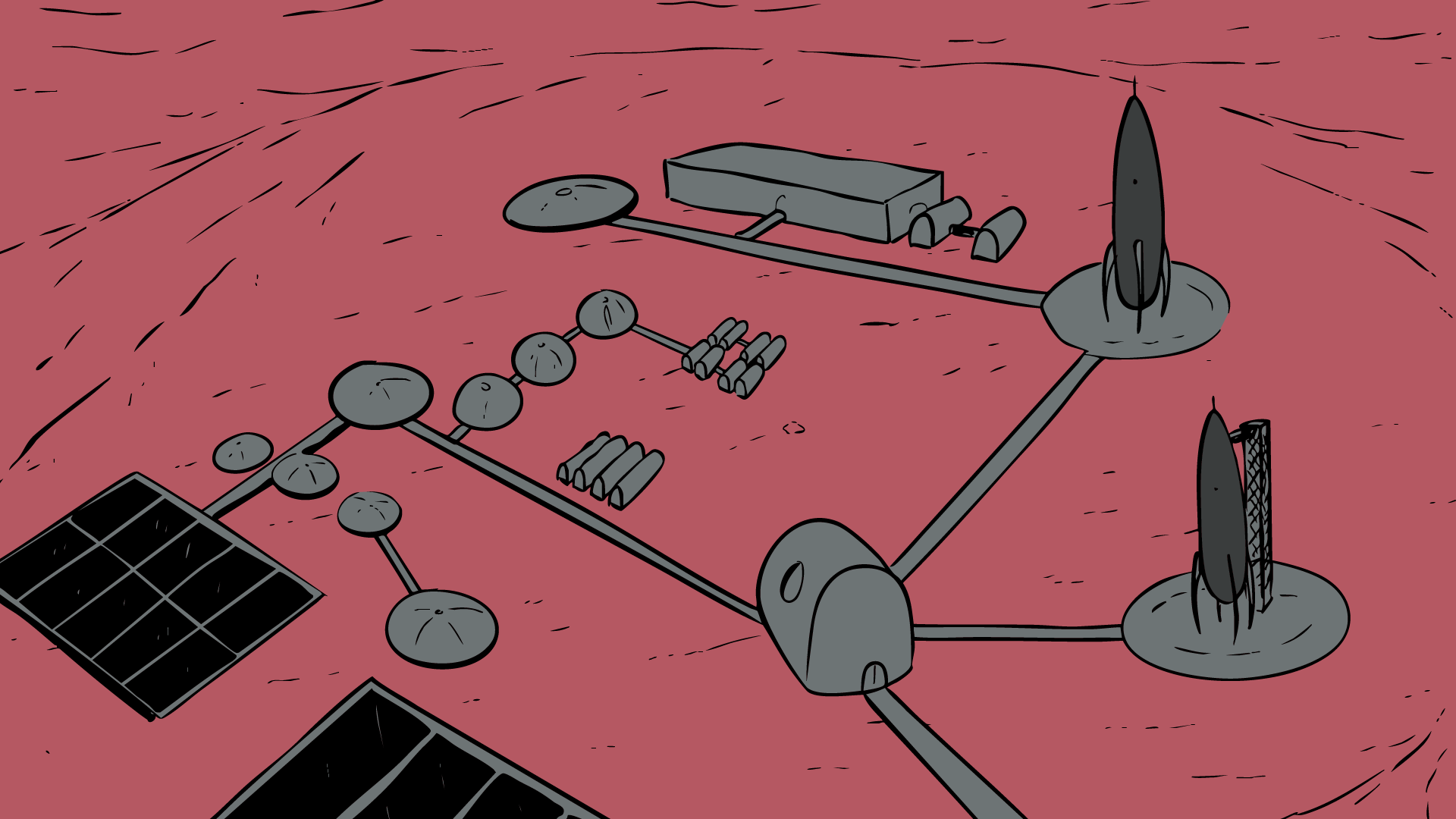

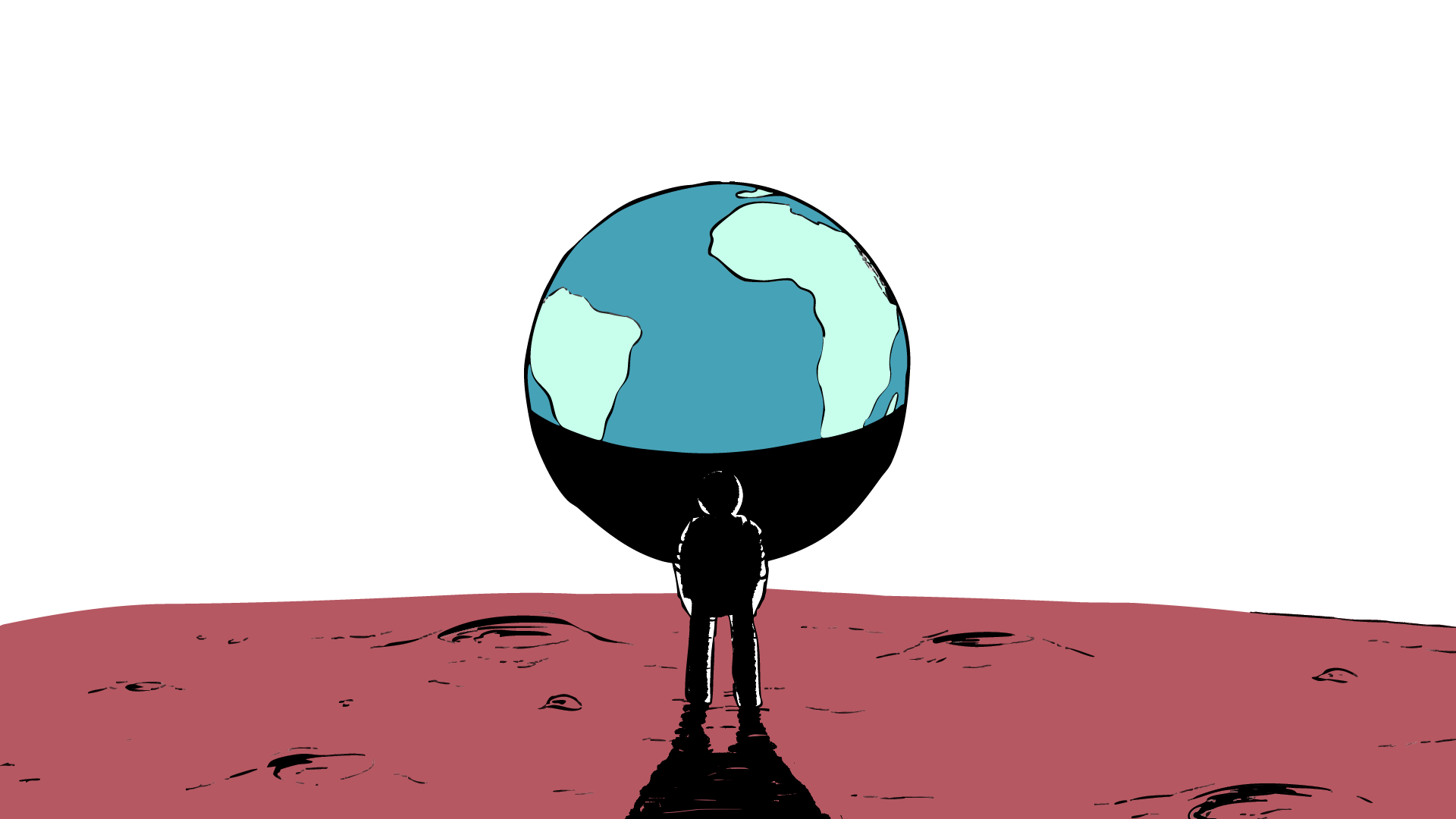

Musk, frequently listed as the world’s richest man, would like to see a one-million person, self-sustaining settlement on Mars in the next 30 years.

This part of the dream is not clearly in violation of international law. The OST denies sovereign territorial claims, but in theory, Musk’s settlers don’t need to do that to simply exist on the Martian surface.

Having a million human beings raise families in an international commons for generations without making any land claims might ultimately get a bit dicey, but in the short term it’s not clearly illegal. But what would clearly violate the OST, is the plan by Musk and fellow travelers to start a new nation in space.

Although Musk’s specific legal position isn’t always clear, a Terms of Service agreement for SpaceX’s Starlink Internet Service is not ambiguous: “For Services provided on Mars, or in transit to Mars via Starship or other spacecraft, the parties recognize Mars as a free planet and that no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities. Accordingly, Disputes will be settled through self-governing principles, established in good faith, at the time of Martian settlement.”

Whether you think this is a good or bad idea, what we can say confidently is that it is incorrect.

The law here is quite clear: Mars settlers are not allowed to form their own nation, which would represent a territorial claim. Moreover, when they arrive on Mars, they will be the responsibility of some Earthbound nation, not free actors. If a bunch of Americans, or Chinese people, or Indians try to set up a Martian claim, effectively they are taking land out of a commons considered to belong to all. This is neither legal nor likely to be geopolitically irrelevant.

Predicting the exact effect of rising tensions is difficult, but to understand the cause for concern, imagine the nation you find most geopolitically threatening announces today that it secretly built a 50-person Moon base.

What’s more, it insists that since the Outer Space Treaty is a worthless relic of a bygone age, it is free to claim thousands of square miles of the lunar surface as sovereign territory of its home state. Perhaps, having landed on the poles, it claims the tiny portion of the Moon that has both water ice and near-perpetual access to sunlight. If you picked America as the nation of concern, how would you expect China to react? Or vice versa.

And lest you think this is just a case of the SpaceX lawyers going rogue, Musk himself recently said that, “The Martians will decide how they are ruled. I recommend direct, rather than representative, democracy. Uncrewed Starships landing on Mars in ~2 years, perhaps with crewed versions passing near Mars, and crewed Starships heading there in ~4 years are all possible.”

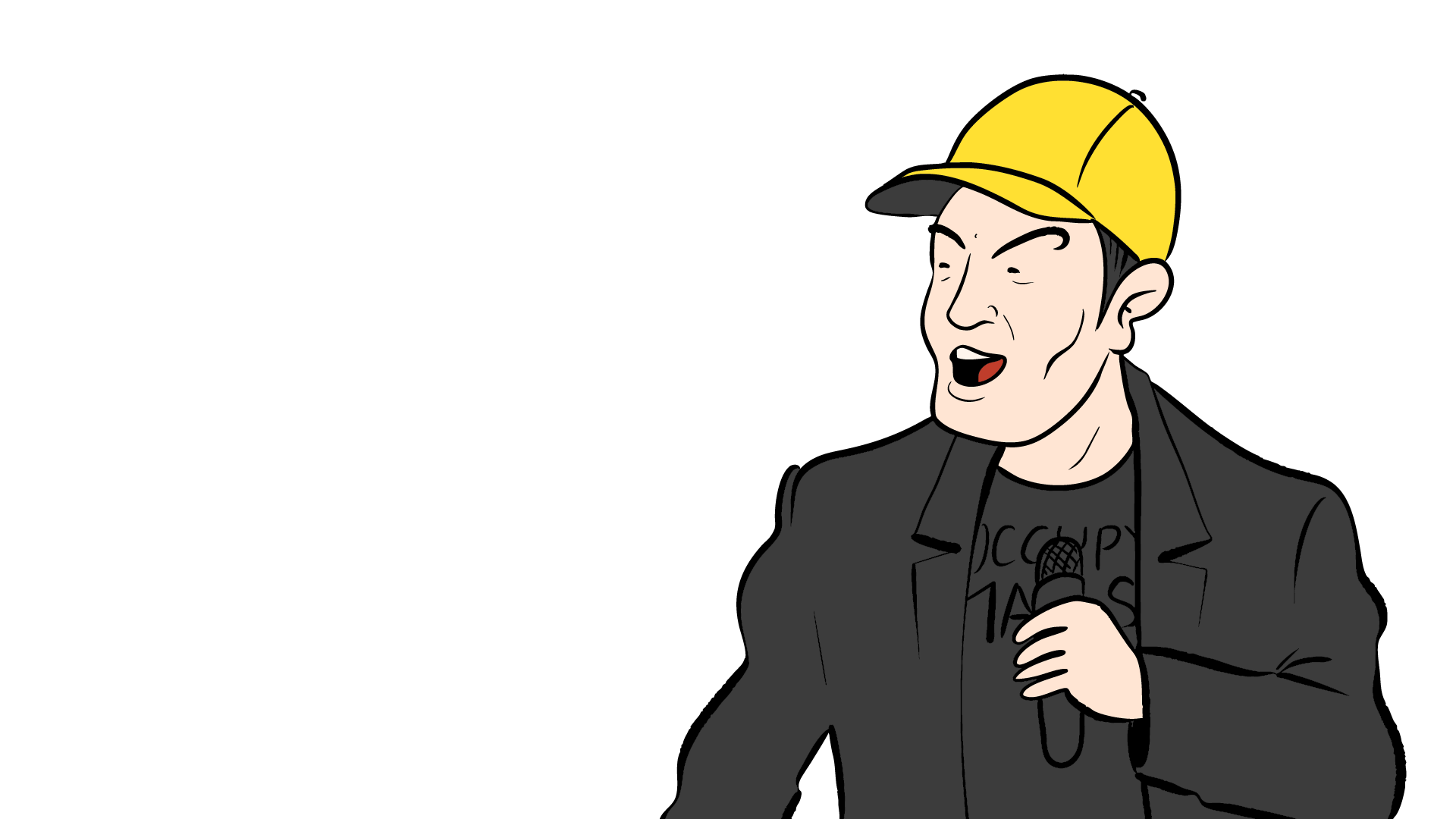

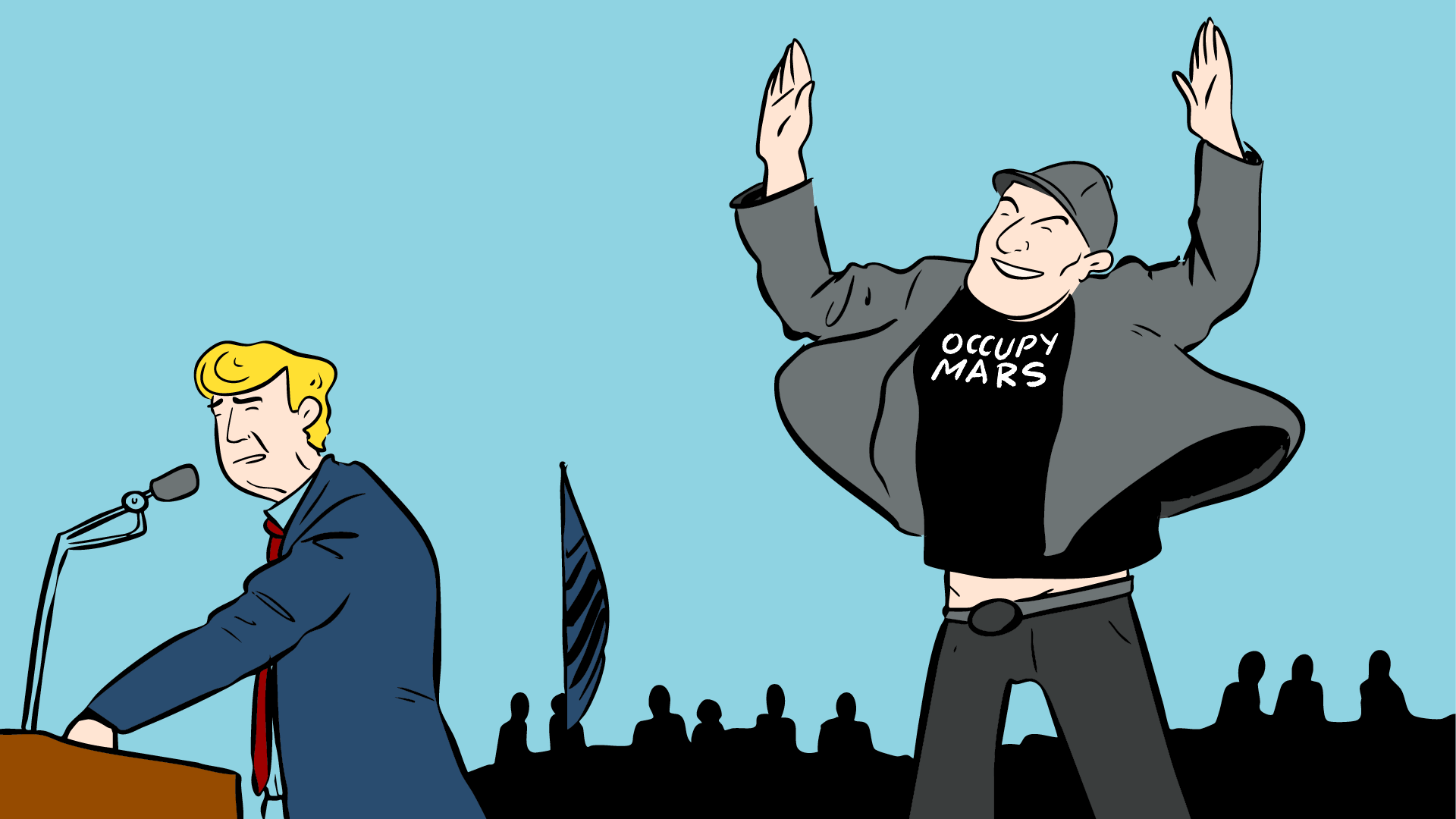

Musk’s disdain for international law is no secret. Recently, in a Town Hall in Philadelphia, he said:

“I’m against globalist power. … I think the UN should not have a lot of power. It’s like, who voted for them? You know, I didn’t vote for them. We want power to the people. Maximum power to the individual.

We should not have any sort of international treaties that restrict the freedom of Americans, and we should minimize the amount of federal interference at the state level… Agencies at the federal and the national level should have minimal to zero power over you.”

What options do we have for forcing Musk to conform to international law?

If launching from the US, any rocket intended to launch Martian settlers would need to be approved by the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). If the plan for a particular rocket launch includes “starting a new nation in space in violation of a long-standing international treaty,” then it would be the FAA’s job to keep that rocket grounded.

But—wait—we hear the chorus of space settlement advocates chanting “how are you going to stop us if we’re already on Mars?”

The plan here seems to be to lie about the intention of the mission, and then set up a new nation upon arrival at the Martian surface, presenting the governments of Earth a fait accompli. Here too though, the United States government retains immense power over the behavior of Martians.

For the foreseeable future, people living on Mars will be absolutely dependent on resupply ships sent from Earth. And many Martians will still have assets that could be seized on Earth. Even from an average of 140 million miles away, Earth has ways of encouraging compliance.

But will it?

When we began writing about this topic, Musk was merely a very rich man in charge of a breakthrough rocket technology. In the years since, he has accumulated political, and geopolitical, power.

In February 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine for a second time, SpaceX provided the Ukrainian military with their Starlink Satellite Internet service. In response, Russian officials at the UN made thinly-veiled threats about blasting Starlink satellites out of the heavens.

Soon after, Starlink restricted use, stopping satellite-internet-enabled drone attacks on the Russian Navy. While we don’t think Musk gave the Starlink units to Ukraine with power in mind, his unique access to space technology gave him power over life and death situations in the middle of a hot war.

Musk’s geopolitical clout has only grown since. Citing concerns that bureaucracy would make getting humans to Mars impossible, Musk threw his considerable fortune and social media empire X behind Donald Trump's presidential campaign.

President Trump has since made his “First Buddy” head of the Department of Government Efficiency, established by Executive Order on Trump’s very first day in office. And, to Musk’s delight, during his inauguration speech, Mr. Trump namechecked the philosophy underpinning America's 19th century wars of conquest westward, saying,

“And we will pursue our manifest destiny into the stars, launching American astronauts to plant the Stars and Stripes on the planet Mars.”

Will a very Musk-friendly Trump administration be willing to put the brakes on Musk’s Martian ambitions? If not, will the international community respond? Their main option for a response would likely be sanctions, either on the US or on Mr. Musk’s overseas business interests. But given the size of the American economy, and of Mr. Musk's wallet, it’s unclear how successful this might be against a determined US administration.

So here we are. The OST, born in fear, designed in part to avoid 19th century style territorial scrambles remains in place. Partially this is because it has served the interests of Earth nations, and partially this is because technology has limited human expansion. Today, the technology is catching up with the space ambitions of the 1960s, and much of that is down to one company: SpaceX. Its leader seems adamant about starting a nation in space, and with his growing political power it’s not clear the United States will stop him.

Although we are skeptical of the idea of a million-person Mars city any time soon, we believe space expansion will eventually happen. And while the first Space Race was a peaceful contest to perform a specific mission, the rhetoric surrounding the Moon and Mars today often concerns territory and mineral access. A contest between nuclear powers is concerning; a turf battle between nuclear powers far more-so. And while traditionally, human spacefaring is mostly about national prestige, a scramble for territory might offer the victor something altogether new: a chance to rewrite the rules.

In his 1962 speech at Rice University, president Kennedy said of the then-new science of spacefaring his nation had entered into: “only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theater of war.” Thanks in no small part to Mr. Musk, the United States now has that pre-eminence.

If the world’s most powerful nation, helped along by history’s most powerful rocket company, were to scrap international space law, it would have consequences that may echo for centuries.

SpaceX. Starlink Terms of Service. https://www.starlink.com/legal/documents/DOC-1020-91087-64.

Schmitt, Eric. "Musk Gives Starlink Terminals to Ukraine and Determines Where They Get Used." New York Times, September 8, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/08/world/europe/elon-musk-starlink-ukraine.html.

Baker, Peter. "Musk Spends Over a Quarter of a Billion Dollars on the Trump Campaign." New York Times, December 5, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/05/us/politics/elon-musk-trump-rbg-election.html.

Musk, Elon. Interview on X (formerly Twitter). "Elon Musk Cites Concerns About Bureaucracy Keeping Us from Getting to Mars." Streamed live. https://x.com/i/broadcasts/1djGXrZpVVXxZ.

Musk, Elon. Interview on X (formerly Twitter). "Musk’s Quote About the UN." Streamed live. https://x.com/i/broadcasts/1djGXrZpVVXxZ.

The White House. "Establishing and Implementing the President’s Department of Government Efficiency." Presidential Actions, January 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/establishing-and-implementing-the-presidents-department-of-government-efficiency/.

Pengelly, Martin. "Vivek Ramaswamy Quits DOGE, Elon Musk Reacts." The Guardian, January 21, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jan/21/vivek-ramaswamy-quits-doge-elon-musk.

I am waiting for the day that Trump suggests that the population of Gaza should be re-settled to Mars…

I’m surprised you didn’t mention the book ‘A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?’

This is an excellent overview of OST, and the ramifications of future space settlements. In my opinion, OST needs to be updated to reflect current realities: if a Mars settlement is ever built, the land it is built on will effectively be “owned” by the settlers or organization that creates it. If a company were to find valuable materials on an asteroid and chose to mine them, they, too, would be the effective owner of the celestial body. Moonbases, the same. Were China and the US to build lunar bases, you can bet they would claim sovereignty over the sites.… Read more »

Does anyone know what China’s CCP and military are doing on the dark side of the Moon?

I really enjoyed the article! I am a professor of space systems. Although our focus is technical solutions, we teach that success is interconnected with the larger mission, politics and must fit within space law. You mentioned that undersea and Antarctic treaty systems. I’m curious if you considered suggesting the sharing and caring for space resources as the native Americans did. I am not an expert in the native American approach. I recall that these folks did not take more than could be replenished. Granted, space objects, ex. Mars and the Moon, do not have active ecosystems. Some other measure… Read more »

Excellent as usual!

(Am I missing something here? Isn’t the earth of the last frame impossible? The light/dark line should have a north to south direction.)

Elon Musk’s SpaceX, and other private space corporations are a threat to Humanity’s Commons in that every chemical fueled rocket launched punches a small hole in the Earth’s atmosphere, directly injecting ozone destroying chemicals and possibly other presently unknown effects. Then there is the issue of the threat of Kessler Syndrome, a possibility that uncontrolled proliferation (cascading collisions creating multiplying bullet speed fragments) of near Earth orbiting space junk, becomes a real threat to operational satellites and crewed space ships. Which if unchecked could theoretically trap humanity on Earth, until enough of the billions+ pieces finally burn up deorbiting, possibly… Read more »

This article states that “Today, the technology is catching up with the space ambitions of the 1960’s.“ Actually, today’s space travel technology is trying to catch up with the technologies of the 1960’s. NASA and its contractors are struggling to put together a crewed lunar landing system as effective as that demonstrated in 1969-72. To date, all the King’s men cannot put Humpty-Dumpty back together again, and the time scale for crewed lunar landings is uncertain. SpaceX was under contract to do a manned lunar flyby in 2023. That didn’t happen. As for Mars, even the most modest human settlement on Mars is… Read more »

I think Trump and Musk should visit Mars in person as soon as possible.

Just because humans are not currently permanently present, nor likely even soon to be permanently present on extra-Earth bodies – or in the Artic or sea bed, for that matter – does not really lessen the concerns about exclusive claims on resources or territory in those areas currently covered by the treaties you mention. Anyone who builds systems or infrastructure for the exploitation of resources in those locations – such as robotic systems to locate, mine, or refine or stockpile natural resources – is highly likely to make investment-back property claims to exclude others from free-riding on their investments or… Read more »

Is this article aimed at children?

I don’t care for the format/animation.

I admit that I’m old.

There is no chance for humans to settle on Mars for many decades. Even the first human exploration of Mars is several decades away since the challenges to be overcome are mind-boggling, the costs are astronomical, and the risk of failure with loss of human lives will remain high even after the challenges are met. Yet, it is very useful to raise the sort of issues that this article mentions since space exploration and colonisation efforts may have major impacts here on Earth by normalizing approaches based on exceptionalism. Exceptionalism was always used to justify colonialism and imperialism.

We have a very usable planet called Earth that could remain habitable if we put funding to reverse global heating instead of going to Mars. To be clear, I loved space missions, having been involved in both deep space missions as well as earth orbital. BUT, let’s go to Mars AFTER we clean up our mess on Earth.

This intersting discussion avoids the question of practicality. The ventures to settle people on Mars look infeasible, judging by a neglected article in the NYT 3 decades ago by a serving USN psychiatrist who revealed that the turnover of crew in the USN nuclear submarines which routinely stay underwater for weeks at a time is approx 10% p.a. – annually about one in ten of these highly selected personnel has to be rotated out of that line of work for reasons of mental instability. The Mars voyages and attempted residences would be at least as prone to psychiatric breakdown. Musk’s… Read more »

If you want regular people to read this article then drop the cutsie distracting, and counterproductive format.

Musk went from hero to zero in just a few years, what wasted potential.

Is there a plain text version of this? For those really not into the comics culture.