Four years later, member countries are still divided about what the nuclear ban treaty means

By Michal Onderco, Valerio Vignoli | April 24, 2025

Annie Jacobsen (2nd from left), author of the book Nuclear War: A Scenario, addresses the third meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons at the UN headquarters on March 4, 2025. The meeting is chaired by Akan Rakhmetullin (4th from left), First Deputy Foreign Minister of Kazakhstan. (Credit: UN photo)

Annie Jacobsen (2nd from left), author of the book Nuclear War: A Scenario, addresses the third meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons at the UN headquarters on March 4, 2025. The meeting is chaired by Akan Rakhmetullin (4th from left), First Deputy Foreign Minister of Kazakhstan. (Credit: UN photo)

The participants in the meeting of states parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), also known as the ban treaty, adopted their draft declaration and a list of decisions in March. It is the third and last meeting of state parties since the treaty entered into force in January 2021. With these documents, the ratifiers are set to have the treaty’s first review conference in November 2026.

Since 2022, we have studied how countries position themselves toward the treaty. This allowed us to understand the gray areas that exist between ratifying and not ratifying the treaty, a dichotomy that its supporters often adopt. By analyzing speeches delivered in the meeting, and turning them into measurable positions based on observed word frequencies, we first showed that the simplistic narrative that divides states into two monoliths—those in the treaty and those outside—was too simplistic. In a second analysis, we observed a phenomenon by which states that are joint members in nuclear weapons-free zones tend to develop similar views about nuclear weapons, which then are integrated into new institutional settings such as the TPNW (a phenomenon scholars call “regional socialization”).

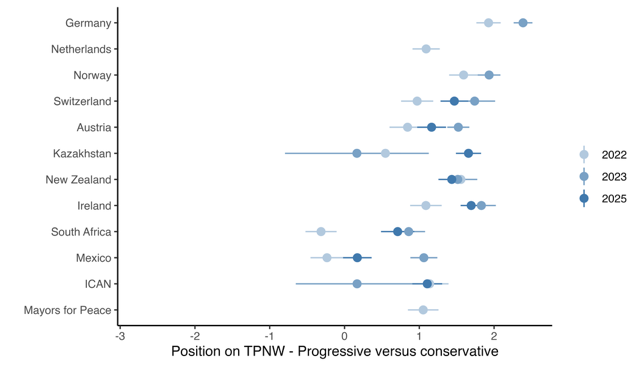

The March meeting allowed us to go one step further and look at how the states’ views of the ban treaty have evolved. Our analysis reveals that member states were able to bridge key differences while maintaining a diversity of views. But our analysis also shows that states, on average, moved toward a more conservative view of the treaty in the last three years, and that the TPNW community remains divided over the war in Ukraine and unable to condemn Russia as the aggressor.

As the TPNW is gaining prominence as an international security forum, the challenge now is to maintain such viewpoint diversity and not become an echo chamber.

What has changed. The treaty process itself has evolved since 2022: The TPNW now has a fully functional inter-sessional process, has a specially mandated scientific advisory board, and has developed relations with a broad cross-section of academic experts. The TPNW community was also reinvigorated after the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Nihon Hidankyo—a grassroots movement formed by survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings and nuclear weapons testing (or Hibakusha)—for its nuclear disarmament efforts.

Much has changed over the last three years: The international security situation has arguably become worse, not better, and the risk of nuclear weapons use has increased. In addition, in countries under the nuclear umbrella of the United States—a prime target for the ban treaty advocates—public attitudes swung in favor of nuclear weapons. No NATO members participated in the March meeting as observers, despite four NATO countries participating in the first meeting in Vienna in 2022 and three in New York in 2023.

To study the evolving dynamics of TPNW meetings since 2022, we used an open-source computational model called Wordfish to analyze the speeches delivered by state representatives and civil society participants during the general debate at the conference (184 in total; except for a few unavailable statements). This tool scans texts for word frequencies to identify word distribution patterns, allowing it to position speakers along a single-dimensional scale. The method operates on the premise that specific word choices—or their absence—indicate where political actors align on this scale. Wordfish identifies positions of political actors on a dimension, which is replicable and not biased by possible individual variation among human coders. This lack of “supervision” in the estimation process makes this tool particularly attractive for political scientists who seek to measure existing cleavages from texts on several issues, including climate change and military interventions, without imposing any category “ex ante.”

The scale derived by the algorithm has no inherent meaning. To give meaning to the scale, one needs to look at the words associated with its extreme ends. After the first TPNW meetings, we showed that states aligned along a scale of which extremes were “progressive” versus “conservative” views of the treaty. On the scale, those participants more on the left (progressives) tend to view nuclear disarmament primarily as a humanitarian problem, whereas those on the right end (conservatives) tend to consider more the security implications of nuclear disarmament.

A more conservative view. Our analysis shows that states, on average, moved toward a more conservative view of the treaty (shift to the right) between 2022 and 2025, although for most states, the position of 2023 was more extreme than this year (see Figure 1). Importantly, even supporters of the treaty, like Austria, have moved closer to the “conservative” view of the treaty.

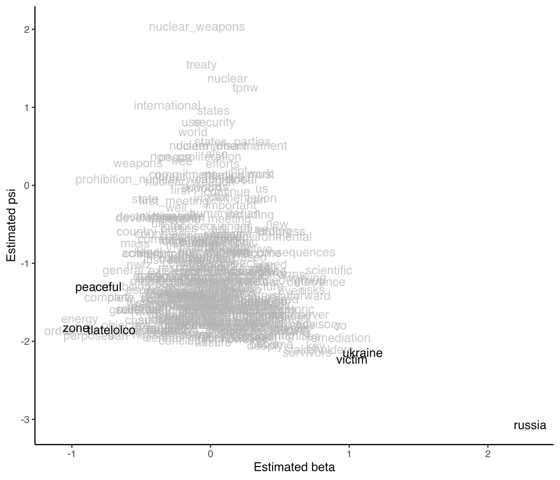

To better understand the nature of this “progressive vs. conservative” cleavage and the drivers of actors’ positions, we looked at the language speakers used in the TPNW meetings. Figure 2 plots all the words used in the delegations’ statements during the meetings, forming an Eiffel Tower shape. The peak of this tower represents words used by nearly all delegations, which means they were used with a high frequency (top) but with a low distinguishing value (center). In contrast, the closer to the legs of the tower (left and right), the higher the distinguishing value of the word, even at relatively low frequency (bottom).

Looking at this tower, we observe that the words on top are those that are most general, such as “nuclear weapons,” “TPNW,” or “treaty”. Words on the left side refer to peaceful uses of nuclear energy, but also the Treaty of Tlatelolco, the first nuclear weapons-free zone in Latin America. In contrast, those on the right refer to “Russia” and “Ukraine,” but also to “survivors,” indicating that the attention to the impacts of nuclear testing is far from being uniform among the member states.

Our previous analysis showed words such as “verification” or “engagement” were among the most discriminating. Verification has now moved more toward the center, indicating that it has become more commonly used. However, engagement has remained a polarizing word, like “deterrence.” Similarly, words, such as “planet,” which were previously rather polarizing, have become more commonplace. These developments indicate that some ideas, such as treaty verification or planetary concerns, are now more broadly espoused by delegations to the nuclear ban treaty, whereas others, such as engagement with non-parties, remain polarizing.

Surprisingly, the word “Russia” remains the most discriminating throughout the whole cycle. While the name of the country waging an aggressive imperial war against a non-nuclear weapon state under a nuclear shadow can be expected to be prominent in speeches about nuclear disarmament, the fact that the word remains highly polarizing indicates that the TPNW community remains divided over the war in Ukraine and unable to condemn the aggressor. This trend continued throughout the March meeting, which also came only a few days after President Donald Trump refused to recognize Russia as the aggressor in the war.

Keeping diversity. Overall, our analysis demonstrates that the states’ views on the TPNW do evolve. The parties to the TPNW—and those outside—are not a monolith but, rather, continue to develop a nuanced view of the treaty. These findings provide enough material not only for academics interested in the development of the nuclear ban treaty but also for practitioners seeking to understand where the treaty process is heading.

As the TPNW members now prepare for the first review conference at the end of 2026, they would be well-advised to think about some of the key differences among the member states that until now have been papered over, including the attention given to the affected communities or positioning themselves against aggressors brandishing their nuclear weapons. At the same time, the first meetings have shown that state parties have managed to bridge real differences. One final challenge remains: not to become an echo chamber. As the participation of the non-parties declined in 2025, this risk has become higher than before.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty, Russia, TPNW, disarmament, nuclear disarmament, treaty verification

Topics: Nuclear Weapons