Government officials are letting AI do their jobs. Badly

By Emily M. Bender, Alex Hanna | May 30, 2025

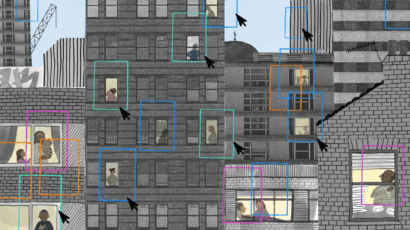

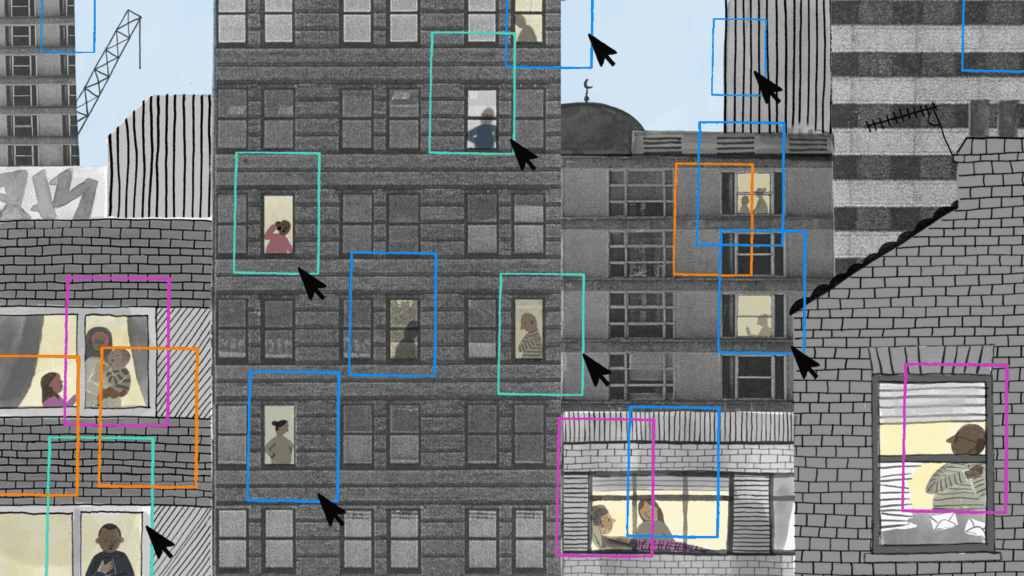

A chatbot instructed New York City landlords to discriminate based on whether potential tenants need rental assistance, such as Section 8 vouchers, according to an investigation. Image: Emily Rand & LOTI / AI City / Licensed by CC-BY 4.0

A chatbot instructed New York City landlords to discriminate based on whether potential tenants need rental assistance, such as Section 8 vouchers, according to an investigation. Image: Emily Rand & LOTI / AI City / Licensed by CC-BY 4.0

Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna’s new book, The AI Con, published in May 2025 by Harper. Used with permission.

National, regional, and municipal leaders have become enamored by AI hype, in particular by finding ways to offload the responsibilities of government to generative AI tools. This has included providing tools for guidance to their citizens and residents on how to navigate city ordinances and tax codes, translating asylum claims at the border, and providing massive contracts to companies who say they can shore up the lack of well-trained professionals for public health systems. But synthetic text extruding machines are not well suited to handle any of these tasks and have potentially disastrous results, as they can encourage discrimination, provide patently wrong advice, and limit access to valid claims of asylum and movement.

In New York City, Mayor Eric Adams (former cop and wannabe tech bro) has thrown resources at technological toys, with results ranging from laughably ineffective to dangerous. This includes a short-lived New York City Police Department robot that was meant to patrol the Times Square subway station and needed two uniformed human minders to deter would-be vandalizers. Adams and his administration released a broad-reaching “AI Action Plan” that aims to integrate AI tools into many parts of city government, the centerpiece of which was a chatbot that could answer common questions for residents of the Big Apple.

Unfortunately, that chatbot isn’t able to reliably retrieve and convey accurate information; like all LLM-based chatbots, it was designed to make shit up. A 2024 investigation by The Markup, Documented, and the local New York City nonprofit The City revealed that the tool tells its users to flat-out break the law. The chatbot responded that it was perfectly okay for landlords to discriminate based on whether those potential tenants need rental assistance, such as Section 8 vouchers. It also stated confidently that employers could steal workers’ tips and could feel free to not inform workers of any significant schedule changes. These mistakes would be hilarious and absurd if they didn’t have the potential to encourage employers to commit wage theft and landlords to discriminate against poor tenants. Despite all these rampant errors, the chatbot interface has all the authority of an official New York City government page.

California is the home of Silicon Valley, and accordingly, the state government has gone all in on the use of AI tools. In 2023, Governor Gavin Newsom signed an executive order to explore a “measured approach” to “remaining the world’s AI leader.” A California Government Operations Agency report suggests a number of potential uses of “GenAI” (that is, synthetic media machines), including summarizing government documents or even translating government computer code into modern programming languages, and required state agencies to explore the use of generative AI tools by July 2024.

In a particularly alarming use case, the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration is developing a chatbot that would aid their call center agents in answering questions about the state’s tax code. Although the department said that this is an internal tool that will have agent oversight, the call for proposals states that the tool should “be able to provide responses to incoming voice calls, live chats, and other communications,” according to journalist Khari Johnson. The governor has also said the state has an ongoing pilot project to address homelessness. In his proposal, generative AI systems are supposedly helping identify shelter-bed availability and analyzing the state budget. These seem like jobs for people with access to databases rather than something you’d ask ChatGPT. Text extruding machines extrude synthetic text, not housing.

At the US border, language models and associated technologies are already being used in ways that have dire consequences. Here the technology in question is machine translation, which predates ChatGPT-style text extrusion machines but also uses language models. The United States Customs and Border Protection uses machine translation to process asylum claims. Those seeking asylum have a right to translation for written documents and interpretation for spoken language. But the reliance on machine translation tools has the potential to ruin a claim of asylum due to major errors. For instance, Respond Crisis Translation, an organization that provides human translators for asylees and other people in crisis, reports that translation errors can easily become grounds for denying an asylum claim and returning refugees to dangerous conditions in their home countries. “Not only do the asylum applications have to be translated, but the government will frequently weaponize small language technicalities to justify deporting someone. The application needs to be absolutely perfect,” says Ariel Koren, the executive director and cofounder of Respond Crisis Translation.

In the United Kingdom in 2023, then–prime minister Rishi Sunak convened a summit around AI held at Bletchley Park, referring to AI as the “greatest breakthrough of our time.” However, there are already many uses of AI in the United Kingdom that are having detrimental effects for those intimately involved with its outcomes. It was, after all, only three years before that masses of students marched in the streets, chanting “fuck the algorithm!” in opposition to algorithmic decisions that scored their A-level exams.

The Sunak government went all in on generative AI. In early 2024, Deputy Prime Minister Oliver Dowden announced plans to use LLMs to draft responses to questions submitted by members of Parliament and answers to freedom-of-information requests. (We find this a really telling commentary on the government’s attitude towards freedom-of-information requests. If they’re willing to use a text extruding machine to provide responses, they clearly don’t care about answering accurately.) And in 2023, Sunak announced that the National Health Service (or the NHS, the United Kingdom’s public healthcare system) would be implementing chatbots all over the place. The text extruding machines would be used to transcribe doctors’ notes, schedule appointments, and analyze patient referrals. The NHS also announced, in mid-2023, that it had invested £123 million to investigate how to implement AI throughout the system, including brain, heart, and other medical imaging, and was making another £23 million available for these technologies. According to Sunak, these plans will “ensure that the NHS is fit for the future.” We beg to differ: throwing synthetic text into patient interactions and patient records sounds like a recipe for chaos, dumped on an already overstretched workforce.

Research is already revealing the problems of using these tools in patient care. The privacy implications are enormous: Health care researchers have remarked that providers are already using public chatbots (such as ChatGPT) in medical practice. Inputting data into ChatGPT allows OpenAI to use those data to retrain their models, which can then lead to leaking of patient information and sensitive health information. Patients are worried about these data issues too; research by the digital rights advocate Connected by Data and patient advocates Just Treatment found that people are highly concerned that their data may be resold, or that large firms will not sufficiently protect their health information. This concern is even more piqued, as the contract to construct the “Federated Data Platform” which the NHS plans to build out its services has been awarded to Palantir, the military and law enforcement technology company founded by tech investor Peter Thiel.

The British government’s headlong rush to deploy AI extends to the courts as well. A Court of Appeal judge used ChatGPT to summarize legal theories with which he wasn’t familiar and then directly pasted the output into a judicial ruling, calling the tool “jolly useful.” We were a little less than jolly upon hearing about this shocking usage, but even worse is that the UK Judiciary Office gave judges the okay to use tools like ChatGPT in the courtroom. The mild caveats offered by the Judiciary Office warn that synthetic textextruding machines are not authoritative, possess biases, and do not ensure confidentiality or privacy. But with such high-risk uses, why is this office suggesting that judges should be using these tools at all?

These government leaders—Adams, Newsom, and Sunak—have accepted generative AI into the work and operation of government with confidence and enthusiasm. All of them use words such as “ethical,” “responsible,” and the like, but there could be another option: Just don’t use these tools. Government processes that affect people’s liberty, health, and livelihoods require human attention and accountability. People are far from perfect, subject to bias and exhaustion, frustration, and limited hours. However, shunting consequential tasks to black-box machines trained on always-biased historical data is not a viable solution for any kind of just and accountable outcome.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: AI, ChatGPT, artificial intelligence, asylum, chatbot, tech

Topics: Artificial Intelligence, Disruptive Technologies