To win on nuclear energy, the United States should lose reprocessing

By Ross Matzkin-Bridger | May 28, 2025

Trump's executive orders on nuclear energy unfortunately played the prospect of nuclear fuel reprocessing and recycling prominently—even though reprocessing has a history of cost overruns and poses serious security concerns.

Trump's executive orders on nuclear energy unfortunately played the prospect of nuclear fuel reprocessing and recycling prominently—even though reprocessing has a history of cost overruns and poses serious security concerns.

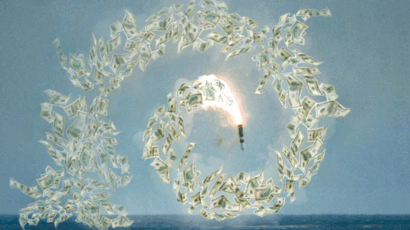

The siren song of spent nuclear fuel reprocessing beckons again, selling a sweet melody that, actually, threatens to stymie hopes of a nuclear energy revival in the United States. A tantalizing technology that promises to recycle the used fuel that comes out of nuclear power reactors into even more reactor fuel, reprocessing is marketed as an elixir that turns refuse into resource. But the marketing ignores serious problems: Reprocessing doesn’t work as advertised and instead has a history of bloating budgets, exacerbating radioactive waste challenges, and creating serious security concerns. Attempts at reprocessing end up draining limited resources that could otherwise be used to support nuclear energy technologies that are proven to work.

So it was disappointing to see reprocessing play prominently in several executive orders on nuclear energy that President Trump signed last Friday. The ambition to foster rapid growth in new nuclear energy is commendable, showing a clear vision for meeting burgeoning electricity demand. But reprocessing would only inhibit this laudable goal.

There is still opportunity to right the ship, however.

There is no magical solution for eliminating nuclear waste—the highly radioactive, non-recyclable fission products that are created in all nuclear power reactors. While we do know how to safely and effectively manage this material, reprocessing it only creates more problems. Instead of keeping spent fuel safely intact, reprocessing breaks it down, creating new types of solid, liquid, and gaseous wastes. These wastes need to be converted into manageable forms and disposed of in a mix of deep geological repositories and specialized landfills. Far from negating the need for a permanent repository for nuclear waste, reprocessing creates a larger mess and detracts from the resources available to manage waste in a simpler way.

Rather than aid a nuclear renaissance, the controversy surrounding reprocessing fractures the nascent, broad, and delicate coalition that has formed to support a responsible and common-sense nuclear energy expansion.

Despite claims that reprocessing can foster the reuse of over 90 percent of the elements contained in spent fuel, the few countries that have tried commercially deploying the technology have struggled to recycle even one percent. A prime example is the United Kingdom, which reprocessed for nearly six decades, recovering more than 100 tons of plutonium and thousands of tons of uranium that were supposed to be recycled. Instead, the material mostly just sat in storage, piling up over the years as the technical and economic challenges of reusing it mounted. The security challenges for the plutonium were also immense, as a small chunk the size of a soda can is all that a criminal or terrorist would need to have the building block of a nuclear bomb.

There is also the problem of a mature reprocessing and recycling program creating a global economy in plutonium fuel that could be diverted—whether by terrorists or governments—for use in nuclear weapons. Because of this never-ending quagmire, in 2022, the UK government decided to abandon reprocessing and dispose of its stockpiled fissile material. Even with the billions of dollars sunk into reprocessing over the decades, trying to recycle the recovered material as nuclear fuel was going to be more costly than simply throwing it away.

The costs of reprocessing are a key consideration as the United States aims to harness limited taxpayer resources to rapidly deploy new nuclear power reactors. In last week’s executive orders, the Trump administration set a bold new goal of quadrupling nuclear energy capacity by 2050. This lofty ambition can only be realized through a hyper-focused effort on lowering costs and decreasing financial risk for the workhorse nuclear technologies that are ready or nearly ready for deployment. We have cutting-edge technologies with established or feasible supply chains—without the need to bet billions of dollars on the development of untested new reprocessing facilities. An expensive flirtation with reprocessing is not compatible with rapid nuclear energy scaling.

Reprocessing is a chimera, not a panacea. It is fortunate that there are two important pathways for stopping it in its tracks here in the United States. First, the executive orders wisely call for a series of reviews into the feasibility of reprocessing. These assessments must not be perfunctory rubber stamps but should take critical looks at the harsh realities of reprocessing, adjusting policy accordingly. Second, Congress ultimately has the power to determine how funds are appropriated, and it should decline to fund reprocessing and instead focus limited resources on efforts that will actually aid the broader goal of ushering in an American nuclear energy revival.

The dream of turning waste into a valuable commodity has ignited the human imagination for centuries. But just as the alchemists of generations past were never able to turn their toils into a solution for changing lead into gold, real world experience and science show that reprocessing doesn’t live up to the hype. There is a better path that avoids this foolhardy distraction. Let’s take it.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Trump executive orders, nuclear energy, nuclear power, nuclear recycling, nuclear reprocessing

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Risk

Although the comments on the history of reprocessing are correct, it should be recognised that, with expanding nuclear power and increased environmental concerns, the benefits of fuel recycling should be re-examined. This, of course, is the justification of interest in this option in countries like Japan without significant U resources. Many past problems – and continuing issues in plants like Rokkasho in Japan – result from the use of fossilised wet chemistry technology that can be traced back to the weapons programmes of the ’40s and ’50s. Advances in material processing over the last 70 years may be able to… Read more »