Will America be “flying blind” on bird flu? A key wastewater-tracking program may soon end

By Matt Field | May 3, 2025

A researcher collects a wastewater sample in New York City. Nearly half of the US population is now covered by wastewater disease surveillance. (Credit: NYC Health + Hospitals)

A researcher collects a wastewater sample in New York City. Nearly half of the US population is now covered by wastewater disease surveillance. (Credit: NYC Health + Hospitals)

Peering into wastewater for public health has a history dating back at least to the late 19th century, when a biologist in Boston cultured sewage in beef jelly, bouillon, boiled potatoes, and milk to see if anything would grow. Later, scientists in Scotland looked at wastewater to assess the spread of typhoid. After injecting monkeys with sewage in the 1930s, American researchers realized that wastewater polio virus concentrations correlated with community infections. It was the COVID-19 pandemic, however, that led to skyrocketing investment in wastewater disease surveillance in the United States—this time with the aid of modern biotechnology and without bouillon or monkeys.

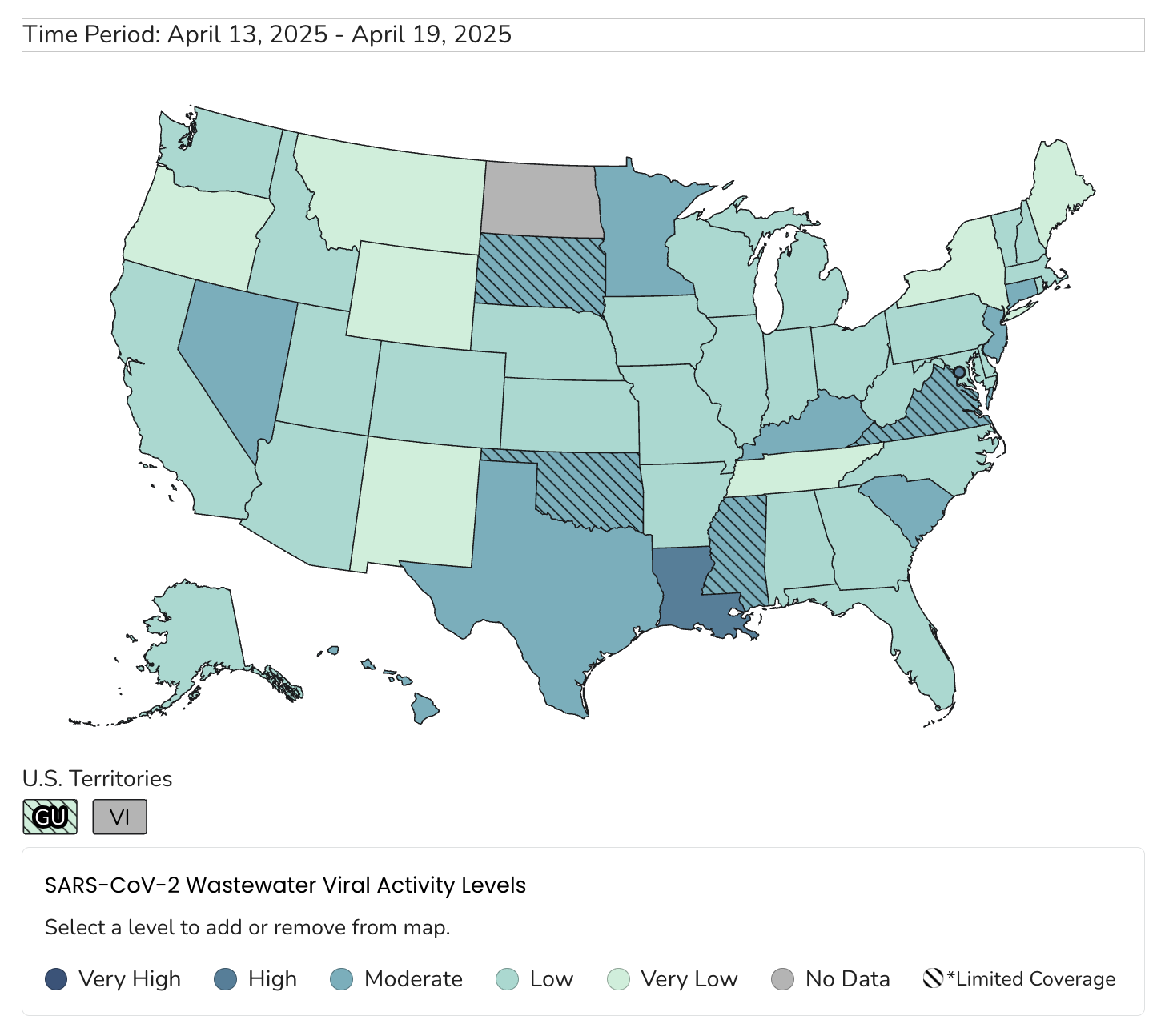

As COVID transitioned from a deadly novelty to something closer to a mundane nuisance, testing for the virus fell off a cliff. Wastewater surveillance became central to public health officials’ ability to track COVID. The same is true for other threats, like H5N1 avian influenza. Bird flu has now spread from wild birds, to poultry, to cattle, and, worryingly, to a wide variety of other mammals, including people. Still testing remains limited. The federal government has invested at least $500 million in building wastewater-surveillance capacity since 2021. But that funding expires in September. Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist who is the director of The Brown University Pandemic Center, told me we may soon be left with an even murkier understanding of how diseases like COVID and bird flu are spreading.

“We’re kind of flying blind, and we will be totally blind if we get rid of wastewater,” she said of H5N1 surveillance when I spoke with her in late April. While some potential use cases of wastewater surveillance, like the ability to track infections to specific buildings or test for drug use, raise ethical questions, wastewater testing is overall one of the most exciting developments of the pandemic era, she said. She worries that it could disappear later this year. “What I keep hearing is that this could go away as of the summer,” Nuzzo said. “I have gotten multiple confirmations from people that there is deep concern about that.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Matt Field: What is wastewater surveillance?

Jennifer Nuzzo: The way I would describe it as is one of the most exciting things to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was used beforehand, but it wasn’t used in the way that we’re now thinking about how it could be used. Part of why we came to even look to wastewater is because, one of the greatest challenges throughout the pandemic was testing. We just never seemed to have enough tests. They never seemed to be where we needed them. And there were always deep biases in terms of who was getting tested and who wasn’t. And that really hindered our abilities to track the virus and to understand where it was and where it wasn’t. Wastewater surveillance helps us with those challenges. It doesn’t fix them entirely, but it helps us with those challenges.

What’s nice about wastewater and other environmental testing is it doesn’t rely on having to have enough tests and making sure that the tests are where the sick people are. It doesn’t rely on having people decide to go out and get tested. It just gives you a common picture of how much virus is out there and where it is.

How granular is wastewater data?

Let’s just look at the pathogens that we are using it for, H5 and COVID. Basically we get a sense of where it is, which is going to be limited by how you sample. If you only sample in one place, you’re only going to know that it’s there or not. You’re not going to know that it’s only there, right? The “where it is” question is only as good as the sampling scheme. Wastewater surveillance is going to tell you the abundance of virus—how much there is—which may translate to how many people are infected. But we can’t really say that because it could also be just an abundance: something is shedding a lot more, or it’s there for another reason. I think the key is that you get a very coarse snapshot of whether the virus is there and—when you do that over time—is it going up, or is it going down? Getting a sense of where you are in the story of an infectious disease is a very useful exercise. It’s right now the main way we are tracking COVID because nothing else is actually useful.

And does wastewater surveillance tell us before the situation gets worse what is happening?

It tends to be a leading indicator, meaning you tend to see it before you would see it in the traditional health surveillance, the other indicators. I would say for COVID, those other ones are really not useful. When I was at Johns Hopkins, I was part of the team with the map, and I spent a lot of time tracking testing. I’m telling you, the test positivity data, I don’t even know how to make sense of it anymore. The hospitalization data are really not there. Deaths are deaths. Death has always been a lagging indicator by a month. Once deaths start going up, that means you’ve had a problem for quite a long time. Right now, wastewater is really the only thing I look at. It is also useful, to the extent that it’s done, for keeping tabs on genomic surveillance—so being able to do pathogen characterization, trying to identify variants, the emergence of variants, and to some extent the relative abundance of a variant, very coarsely.

How has wastewater surveillance evolved since the beginning of the COVID pandemic?

More states now do it. It has also evolved in the sense that locations have added more pathogens to what they monitor. But those decisions are made locally. For instance, many places are now also testing for influenzas. Some places are further testing for H5N1. Whether they’re testing all of their sites, though, is up to the specific location.

The example that I use for why I’m frustrated: There was a case in Missouri who was in the hospital and tested positive for H5N1—there’s still a little bit of a debate over whether H5 put that person in the hospital. We had no idea where the person contracted the infection. It would have been nice to be able to go back to geographically representative sampling results of wastewater to say, “Oh, well, here’s where in the state H5 was detected, and here’s where it wasn’t.” And maybe that would pinpoint a source of infection. Couldn’t do that, because there were so few sites. But also, of the sites that were being tested, only a few of them included H5 in what they were testing for. Most of them were only testing for COVID. That was really frustrating.

Can wastewater surveillance be used to find new viruses?

I think we always have to be mindful this isn’t necessarily a science experiment or just scientific inquiry; that’s what separates surveillance from just satisfying our scientific curiosity. When you’re talking about testing for the purposes of surveillance, you have a duty to act on the results that you have, but it may not always be clear how to do that. There is always a little bit of caution about just simply adding pathogens to your sampling scheme without a clear sense of how you’re going to use it.

I say that because one of the areas of great interest for wastewater is the idea of potentially testing wastewater for unknown unknowns, things we don’t even expect to see. I would argue that is a research question at this point. I don’t think it is a surveillance question. I don’t think we have thought through the science enough of what the limits of detection are or how valid are results, etc. But certainly, we have not thought through the operational response questions to those things. You could theoretically do a lot, but proceed with caution, because more information isn’t always better. In fact, you can imagine some harms.

One of the benefits of wastewater testing is it’s not testing patients. That testing is not the same as a diagnostic tool that gets reviewed by a regulatory authority. One of the reasons why you can test for certain things in an environmental test is that you don’t expect to have to track it back to an individual and in a way that could potentially harm an individual. We saw shades of this in early COVID where the Seattle Flu Study decided to start testing for COVID with uncleared devices. It understandably—you can see both sides of this—ruffled the feathers of the FDA (Food and Drug Administration), who said, “You can’t use that test to test patients.” Because if you get the answer wrong, there will be harms to that patient. Environmental testing isn’t subjected to that.

There are reasons to worry that you could misuse wastewater in those ways, like tracking variants. I won’t specify where we saw this, but there was, at one point, concern that there was this variant and the way that they were testing, they were getting some highly specific information of the test results, such that it was starting to zoom in geographically to the point where you might possibly be able to figure out the source of it, potentially the patient. For me, that’s a giant red flag. This is not an end run around the FDA for diagnostic testing. It cannot be. Nothing will kill the system faster. The work that Hong Kong is doing allowed them to identify affected buildings and quarantine them. I would say that would not fly in the United States.

For privacy reasons?

Yeah, absolutely. First of all, where we are as a nation is not going to allow people to be subjected to the test results for specimens that they did not consent to giving.

We’re talking about infectious diseases, but people have talked about testing for illicit substances. And I would say there are huge ethical issues there that need to be explored, and it is imperative that we explore those and not just follow the science blindly without exploring those issues. Because if you go to the doctor, you generally understand what you’re being tested for, but in the case of wastewater, there’s no opt out.

What are the important public health measures that you can undertake based on the data from wastewater testing?

Let’s go back to the early days of COVID. There weren’t tests to deploy to the public health labs or the clinical labs, etc. And that takes time to work on. We lost time before tests could be available. For a while, we constrained testing. You had to be sick enough to be hospitalized and have come from China, or you had to have traveled back from Wuhan and have these symptoms. We know that the New York epidemic probably was seeded from Europe. Geographically constrained testing, which we do every single time—they did this during Zika, too—it doesn’t work in those early days. We know we’re going to miss stuff, particularly when it’s a relatively fast-moving pathogen.

But wastewater testing potentially allows us to start testing fast. It is a less fraught form of testing than testing patients directly. Imagine if we first turn on wastewater testing and we try to find out: Where is this pathogen? Is it here already? Is it spreading locally? For me that’s a very exciting way to use wastewater.

Right now, there’s no reason to regularly test people for H5N1, obviously symptomatic people. I think it would be helpful to know generally where H5N1 is or isn’t, and one way is just to help us ask better questions about humans.

I also think it could potentially be used for farms because farms are really struggling to keep the virus off their farms. Nobody knows how the virus is turning up on farms or how it’s spreading between farms. We have some vague, very poorly researched hypotheses, but wouldn’t it be nice to give farmers a little bit of a heads up like, “Hey, looks like, H5N1 is really heating up in your area, maybe now it’s not the day to let the chickens go roaming around the fields with the wild birds?” It could help direct biosecurity measures on farms, maybe help them turn them up or down.

Will federal wastewater surveillance continue to be funded?

What I keep hearing is that this could go away as of the summer. I have gotten multiple confirmations from people that there is deep concern about that. I will also say we have multiple different forms of wastewater surveillance, and states may choose to do it on their own. But if we wanted a national picture of what’s happening, the worry is that it would go away. My concern is that states probably won’t keep doing it, because they’re going to have budgetary constraints.

In terms of the United States’ efforts to prevent H5N1 from becoming a pandemic, how big of a hit would it be if federal wastewater surveillance funding dried up?

Let’s just say that the human surveillance is terrible. The testing on farms is pretty terrible. The ag (agricultural) testing is pretty terrible. There’s also questions about the continued availability of ag testing. I’m not an ag person, but I’ve heard from some ag folks that some of the labs and some of the people overseeing the ag testing or ag H5N1 response are either gone or imperiled by recent funding cuts. We don’t really have H5N1 testing. The best we have right now is wastewater, and it’s really limited.

It sounds like ending wastewater surveillance would restrict our ability to control H5N1.

I mean, we haven’t had any reported human H5N1 cases for weeks and weeks and weeks, which could be good news. But I have talked to vets who work on farms, and I said, “Do you think that’s what’s going on, or do you think we’re just not looking for it or reporting it?” And they tell me it’s the latter, that we’re not really looking for it and reporting it. We’re kind of flying blind, and we will be totally blind if we get rid of wastewater. I don’t want to oversell H5N1 testing for wastewater because it’s not what it needs to be right now, but it’s poised to get much, much worse.

How concerning is the overall H5N1 picture at this point for you?

I’m deeply worried. I have seen no data that makes me less worried. Now it’s true, recent infections have largely been mild. But we had a 13-year-old in British Columbia who was hospitalized for more than a month. We don’t know how the 13-year-old contracted it. That does not make me feel good; I’ve got a 12-year-old at home.

A degree of immunity may exist in the population as a result of the H1N1 virus that emerged in 2009, but I don’t know what that means for individuals. When someone asks me, “How worried should I be as someone who works with animals,” I can’t tell them. I don’t know if they have protection and to what degree. I continue to be worried seeing what this virus does to people, seeing what it does to animal models like ferrets, seeing what it has historically done. Historically, 50 percent of the known cases have died.

I will say we are likely missing milder infections. We know this, but all of the serologic studies that have been done, including in high-risk populations, including in outbreak areas, have suggested we miss some mild infections. They have not told us that we are missing a whole lot such that our understanding of the percentage of infections that result in fatalities is vastly off. A lot of people just want to say, “Well, 50 percent case fatality, that’s got to be wrong.” Yes, it’s wrong. COVID was probably 1 percent case fatality. We have a long way to go for H5N1 to be deeply worrisome.

In terms of a pandemic scenario, I have to be clear H5N1 is not the pandemic virus. It has to change to become a pandemic virus, and whether it will change through the small little drifts that we’ve been seeing—that’s a possibility. The most likely scenario that all the virologists will tell you about is that it reassorts with another flu virus, in which case it may not be H5N1. What the next pandemic flu virus will be, and how severe it will be, we just simply don’t know.

But what we do know is that flu pandemics happen regularly. There were three of them in the 1900s. So we have a whole lot of data that we will have another flu pandemic.

Is H5N1 of particular concern, more so than just any other flu virus?

It has long been a worry because we generally understand that pandemic viruses often start in animals then move to humans, and we’ve seen H5N1 do that. It is a particular worry today because in the last two years we’ve seen this virus do things that it didn’t do before: There’s been a rapid geographic expansion and a rapid expansion in terms of numbers of species infected.

A pandemic is a term of geographic spread. It is not a term of severity. We could have another pandemic and have it be mild, or we could have another pandemic and have it be like the 1918 great influenza. We just simply don’t know. There are an increasing number of reasons to be worried about H5N1. I know a lot of colleagues who are certain it won’t become a pandemic. I continue to try to understand that perspective, but so far, I’ve not been convinced that there’s any particular data underpinning that. I think it’s largely based on a belief of “it hasn’t happened, so it won’t happen.” That’s not how statistics work.

Can you characterize for me the US government’s response to the H5N1 threat? There’s been upheaval at the health agencies. How do you think we’re doing?

I’m deeply worried and deeply dismayed by the level of concern that exists for this virus. To be clear, I was very critical of the Biden administration’s response to H5N1, and I continue to be critical of the US government’s response to H5N1 under Trump. I have more reasons to be worried now, because I think we are systematically dismantling many of the systems that exist to protect us from this and many other viruses, including the firing of the USDA (US Department of Agriculture) folks who were working on this and including the lack of information-sharing between CDC (Centers for Disease Control) and state health departments.

There used to be regular calls with outside experts that I would participate in so that I could keep tabs on what was going on. They’re not happening anymore. They haven’t happened since the start of the Trump administration. I cannot conclude anything from that other than stuff’s just not happening. I would love to be proven wrong. I would love them to say, “No, we’re doing all this stuff in the background.” I just see no evidence of it. At the same time, there are a lot of people in public health who will say, “Well, we don’t really think this as the next threat.” I would love that to be the case, but I have no evidence that makes me able to say that. Hope is not a strategy, and I think we are relying way too much on hope right now.

I’m also worried about medical countermeasures, there’s been rumors about potentially canceling contracts with additional vaccine companies. I have worries about surveillance infrastructure and testing.

I don’t think we have faced the facts this virus is not going away. This will be a long-term threat to human health on farms and economic security and economic competitiveness because the United States is so far much more affected than other countries. And the strategies for dealing with the situation on farms, I think, just assume that this virus is going to up and move out of the country or just disappear in a few months. And that’s just simply not the case. It is not going away. We need long term strategies to help farms not become infected with this virus and to rapidly respond if they do.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: H5N1, Wastewater Surveillance

Topics: Biosecurity