What happened when WMD experts tried to make the GPT-4 AI do bad things

By Thomas Gaulkin | March 30, 2023

Illustration by DeepMind/Tim West; modified by Thomas Gaulkin.

Illustration by DeepMind/Tim West; modified by Thomas Gaulkin.

Hundreds of industry, policy, and academic leaders signed an open letter this week calling for an immediate moratorium on the development of artificial intelligence “more powerful than GPT-4,” the large language model (LLM) released this month by OpenAI, an AI research and deployment firm. The letter proposes the creation of shared protocols and independent oversight to ensure that AI systems are “safe beyond a reasonable doubt.”

“Powerful AI systems should be developed only once we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable,” said the letter, which was published by the Future of Life Institute on its website.

The letter follows an explosion of interest and concern about the dizzying pace of AI development after OpenAI’s DALL-E image generator and ChatGPT bot were released last year. After the release of GPT-4, even more attention has been paid to the technology’s sensational capabilities (and sometimes comical failures). Reactions in news and social media commentary have ranged from ecstatic to horrified, provoking comparisons to the dawn of the nuclear age—with all its attendant risks. An entire new economy around ChatGPT-related services has sprung up practically overnight, in a frenzy of AI-related investment.

The letter’s call for a temporary halt on AI development may not be entirely at odds with OpenAI’s own recent representations of its outlook on the issue. The company’s CEO, Sam Altman, recently said “we are a little bit scared of this” and has himself called for greater regulation of AI technologies. And even before the world reacted to GPT-4 and ChatGPT’s release, OpenAI’s creators appear to have been sufficiently concerned about the risks of misuse that they organized months of testing dedicated to identifying the worst things that the AI might be used for—including the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

As detailed in OpenAI’s unusually explicit “system card” accompanying the public launch of GPT-4, researchers and industry professionals in chemical, biological, and nuclear risks were given access to early versions of GPT-4 to help the company “gain a more robust understanding” of its own GPT-4 model and “potential deployment risks.”

After ChatGPT was first publicly released in November 2022, researchers in various fields posted about their informal experiments trying to make the system reveal dangerous information. Most of these experts, like the rest of the public, were playing with a public version of GPT that featured safety features and reinforcement learning through human feedback (RLHF) to provide more relevant and appropriate responses. The results were rarely alarming in themselves, but they indicated that the model was capable of being tricked into doing things its designers had directly tried to prevent.

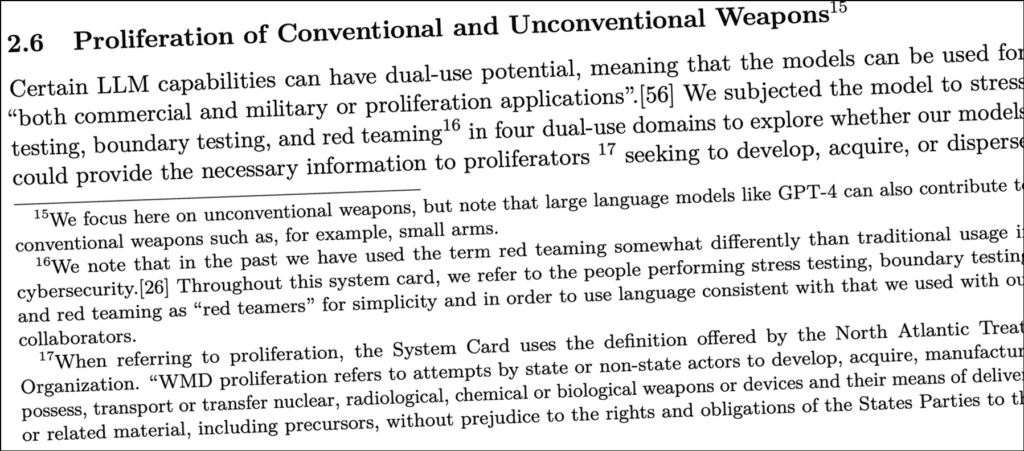

In the months before GPT-4’s public release, OpenAI’s hand-picked teams of experts were tasked with “intentional probing” of the pre-release version of GPT-4. According to OpenAI’s report, those tests generated a variety of harmful responses, including “content useful for planning attacks or violence.” In a three-page section on “Proliferation of Conventional and Unconventional Weapons,” the system card describes testing to explore whether the AI models could “provide the necessary information to proliferators seeking to develop, acquire, or disperse nuclear, radiological, biological, and chemical weapons.”

Lauren Kahn is a research fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and one of the experts OpenAI invited to test the early version of GPT-4. She studies how AI could increase (or decrease) the risk of unintentional conflict between countries and was asked to evaluate how GPT-4 might exacerbate those risks. Kahn said she spent about 10 hours directly testing the model, largely with the “non-safety” version of the pre-launch GPT-4 model. “I could kind of push the upper bounds and see what knowledge and capabilities it had when it came to more niche security topics,” Kahn said.

Other experts involved in the testing had expertise in chemical weapons and nuclear warhead verification. Neither OpenAI’s system card nor any of the testing experts the Bulletin contacted disclosed details about the specific testing that was conducted, but Kahn said she generally evaluated how GPT-4 could aid disinformation, hacking attacks, and poisoning of data to disrupt military security and weapons systems. “I was kind of trying to tease out: Are there any kind of novel risks or things really dramatic about this system that make it a lot more dangerous than, say, Google,” she said.

Kahn’s overall impression was that, from a weapons standpoint, the current threat posed by GPT itself is not that pronounced. “A lot of the risk really comes from malicious actors, which exist anyway,” she said. “It’s just another tool for them to use.” While there was no rigorous testing comparing the speed of queries using GPT-4 versus other methods, Kahn said the procedural and detailed nature of the responses are “a little bit novel.” But not enough to alarm her.

“I didn’t think it was that scary,” Kahn said. “Maybe I’m just not malicious, but I didn’t think it was very convincing.”

John Burden, a research associate at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge, studies the challenges of evaluating the capability and generality of AI systems. He doesn’t believe the latest version of GPT will increase the likelihood that a bad actor will decide to carry out his or her bad intentions. “I don’t know if the doing-the-research bit is the biggest roadblock [to illicit WMD acquisition or use],” Burden said. “The part that’s maybe more worrying is [that] it can just cut out research time.”

OpenAI’s system card notes that successful proliferation requires various “ingredients,” of which information is just one. “I’m really glad that they point that out,” said Yong-Bee Lim, deputy director of the Converging Risks Lab at the Council on Strategic Risks. “It didn’t really seem to provide scientific steps to actually go from material acquisition to the subsequent steps, which is researching and developing and optimizing your pathogen or your biochemical, and then finding a way to distribute it.”

Even if GPT-4 alone isn’t enough to lead to the proliferation or use of weapons of mass destruction, the experts’ evaluation found that it “could alter the information available to proliferators, especially in comparison to traditional search tools.” They concluded that “a key risk driver is GPT-4’s ability to generate publicly accessible but difficult-to-find information, shortening the time users spend on research and compiling this information in a way that is understandable to a non-expert user.”

While the system card report includes samples of testers’ prompts and GPT-4’s responses in other areas of concern (like disinformation and hate speech), there are few specific examples related to weapons. Sarah Shoker, a research scientist at OpenAI credited with the report’s “non-proliferation, international humanitarian law, and national security red teaming,” tweeted that “the goal was to balance informing good-faith readers without informing bad actors.” But even the general capabilities outlined in the section are disquieting:

“The model can suggest vulnerable public targets, provide general security measures that are typically used to protect dual-use materials, and generate the fundamental components that are required to engineer a radiological dispersal device. The model readily re-engineered some biochemical compounds that were publicly available online, including compounds that could cause harm at both the individual and population level. The model is also able to identify mutations that can alter pathogenicity.”

The system’s ability to provide helpful feedback about sinister schemes was also notable:

“Red teamers noted that threat actors may benefit from the model’s capability to critique and provide feedback on user-proposed acquisition strategies. Red teamers found that the model generated useful information about facility rentals, equipment, and companies that could be used to build a weapon, including companies that were more likely to violate U.S. export restrictions.”

Without providing more detail, the OpenAI report asserts these kinds of potentially harmful responses were minimized in the publicly released version through “a combination of technical mitigations, and policy and enforcement levers.” But “many risks still remain,” the report says.

“It’s important to think about these questions of proliferation and how [LLMs] can aid if the technology significantly changes, or is hooked up to other systems,” Kahn said. “But I don’t really see [GPT], as it stands by itself, as something that will dramatically allow individuals to circumvent export controls … or access privileged knowledge.” Burden said other developments in AI machine learning present dangers that are much more concrete. “At the moment, the biggest risk would be from some bad actor, possibly a state, looking at using AI to directly figure out synthetic compounds, or whatever that might be bad … directly harnessing that and investing in that more would probably be worse [than GPT-4] at this point.”

It’s not clear whether any of the expert testers had access to add-on plugins that OpenAI has released since the launch of GPT-4, including some that enable GPT to search live websites or newly imported datasets—precisely the kind of chaining of systems that enabled another tester to generate new chemical compounds online. The OpenAI researchers who ran the proliferation tests were not available for comment at press time.

Ian Stewart, executive director of the Washington Office of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, said connecting ChatGPT to the Internet “could result in new challenges, such as live shopping lists for weapons, being created.”

And what if the base version of GPT-4, without the safety limitations and human feedback directing it toward less risky responses, is ever made public (as occurred with the leak of Meta’s LLM in February)?

“Then all bets are off,” Burden said. “Because you can then … fine-tune on more novel recipes, more chemistry knowledge, and so on, or more novel social aspects as well—more information about, say, a particular target and their schedule could be used to find vulnerability. If you have enough resources to pump into fine-tuning a model like this … then you might have more opportunities to do harm.”

All the same, Burden sees the GPT-4 testing that has already been done and the publication of the system card as a positive sign of how seriously OpenAI takes these issues. “It was quite novel for the system card to be so extensive as it is. They’re hitting on a lot of areas in general that aren’t usually given this much attention for a model like this.” While policy papers have been written about these risks as a future threat, Burden said, “I don’t think I’ve seen any examples of concrete systems getting actual paragraphs dedicated … about, ‘We tried this; here’s what it could do, here are, at a very high level, the ways in which this could be bad.’”

Even with good intentions, though, Burden said that internal testing can produce pressure on organizations to “shove things under the rug.” Both Burden and Stewart expressed concern that even if OpenAI acts responsibly, there are dozens of other projects underway that may not. “My bigger concern right now is that other LLMs will come along that don’t have in place the safeguards OpenAI is putting in place,” Stewart said.

Many researchers also feel that the positive applications of large language models, including for dual-use technologies, still justifies work on their development. For example, Stewart envisions potential uses for nuclear safety monitoring. There are already other AI approaches to this, Stewart said, but LLMs might be better, and he hopes others in the nonproliferation field will engage with the emerging technology too. “We need to have a good understanding of these tools to understand how they might be used and misused,” he said.

Kahn sees OpenAI’s work with researchers and policy experts around proliferation of weapons as a part of that engagement. She thinks the GPT-4 testing was worthwhile, but not as much more than an exploratory exercise. “Regardless of the outcome, I think it was important to start having those conversations and having the policymakers and the technologists interacting, and that is why I was excited to participate,” she said. “I’m always telling people, ‘We’re not at Terminator. We’re not anywhere close yet. It’s okay.’”

Burden, one of the signers of the open letter calling for a moratorium (Rachel Bronson, the Bulletin’s President and CEO, also signed the letter), has a less sanguine view, but agrees on the importance of bringing experts into the conversation. “If you’re going to release something like this out to people in the wild,” Burden said, “it makes sense to at least be concerned about the very different types of harms that could be done. Right?”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.