Conducting public health workshops in Ukraine—under threat of missile attack

By Filippa Lentzos | September 18, 2023

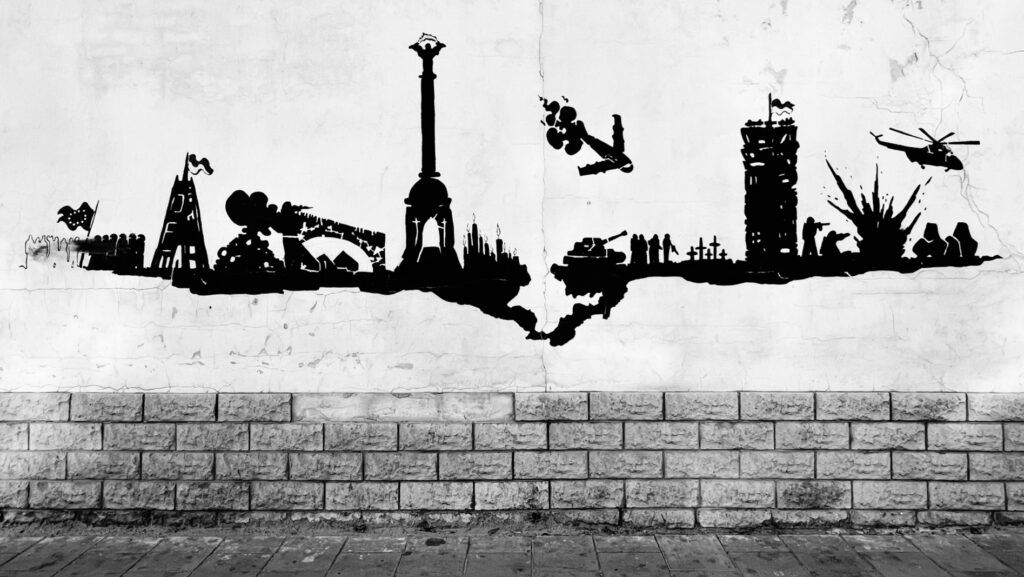

A mural in Lviv, Ukraine, depicting the war. Credit: Filippa Lentzos.

A mural in Lviv, Ukraine, depicting the war. Credit: Filippa Lentzos.

We drove across the border from the wide, modern motorways of Poland onto Ukraine’s single-lane, potholed backroads. Small villages dotted the landscape. Churches were everywhere, their golden onion-domes glistening in the morning sun. So were churchyards with freshly prepared graves, stark reminders of the on-going war.

Ukraine is vast, and I was far from the combat operations in Kharkiv, Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson. But still, the war felt present, and even more so when I reached my destination for the next week, Lviv.

I was in Ukraine to run a series of training workshops for laboratory leads and public health officials. Designed with my King’s College London colleague Gemma Bowsher, the workshops focused on responding to bio-incidents—part of a US Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded project run through the Swiss Centre for Tropical and Public Health. The war has drawn increased political attention to ambiguous disease outbreaks in which it is unclear whether the incident is natural, accidental, or deliberate in origin; the workshops were in part a response to that attention.

The unfolding outbreak of Legionnaire’s Disease in Rzeszow, Poland, a small town turned logistical war hub for the West, is a good example. The outbreak—already infecting several dozens by the time I whizzed past on my way to Ukraine—is most likely of natural in origin. But with this bacterial pneumonia spreading through the water network (as it does all over Europe on occasion), there was concern that, in the context of continuous hybrid warfare attacks, the outbreak could be the result of sabotage meant to sow panic among Ukraine’s allies. Unfounded rumors of Russian responsibility were already circulating.

When I reached Lviv, I was met by Kateryna, a local project partner, who would be looking after me during my stay. (As with the others I’ve featured in this article, I’m only using Kateryna’s first name, for her safety.) Grown up in Lviv, Kateryna now lives in Kyiv with her little family. My simple question when we met—how was your trip?—brought the reality of war closer. She was forced to change travel plans at the last minute so she could attend the funeral of a close friend’s husband, one of the reported 70,000 Ukrainian soldiers who have died since the invasion began on February 24, 2022.

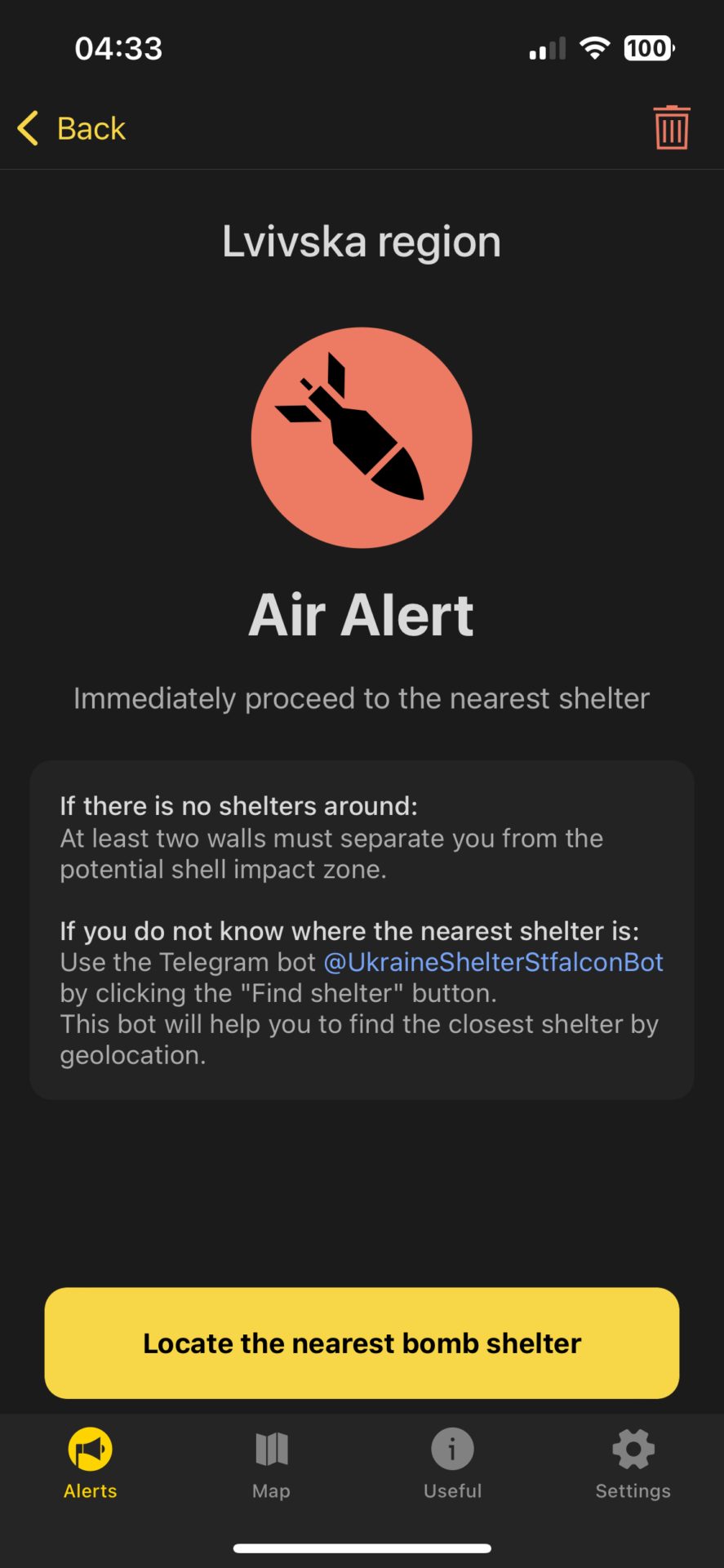

During my first night in Lviv, I was awakened by Kateryna apologetically knocking on my door. There was an air alert, she explained, and we should move as swiftly as possible to the hotel’s basement shelter. Housed in the historic part of the city, the hotel was a bank during the former Austro-Hungarian empire, and its entire basement had been built as a vault. I felt safe there, but quickly read up on Tu-95MS cruise missile carriers and Shahed drones.

Kateryna gave me a crash course on distinguishing between the sounds of incoming Russian missiles and Ukrainian air defenses. I downloaded the real-time “air alert” app with its map of Ukraine and its 24 regions, along with the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Kyiv. This night all regions had turned dark red, indicating an imminent threat of missile attack across the breadth of the country. It took over two hours before the Lvivska region, where Lviv is located, turned from red to grey on the map. The immediate danger had passed, and we could go back to our rooms. Crimea and the far eastern regions remained red, as they did for most of my stay. In the morning, I learned there had been four missiles fired at Lviv, but the air defense held, and the missiles thankfully never made impact.

A couple of days into my stay, a “flash news” post on social media notified that Ukrainian MiG-31K aircraft from the Savasleyka Air Force Base were scheduled to fly in the airspace of several neighboring Russian regions that day. It continued: “The launching of aeroballistic missiles of the Kh-47M2 `Kynzhal’ complex or their imitation is not excluded.” These Russian hypersonic air-launched ballistic missiles are fast (up to Mach 10) and have a long range (1,500-2,000 km). As someone noted to me, you don’t want to meet one.

That night, the sound of the air alert alarm from my app woke me up. We again hurried to the basement. In one of the largest-scale attacks on Russia in months, Ukrainian drones had attacked at least six regions deep within Russia, including an airfield in Pskov, 800 km from Ukraine’s border, where they had significantly damaged four IL-76 military transport planes. Russia’s foreign ministry spokesperson, Maria Zakharova, said the Ukrainian drone attacks “will not go unpunished.” The repercussion came quickly.

On the phone from the hotel basement to her husband and six-year-old, who were hunkering down in their Kyiv apartment bathroom, Kateryna did not hear the comforting low thunder of Kyiv’s air defenses but instead the whoosh of incoming missiles. Russia had launched the largest attack on the city since spring. We later learned Russia had attacked with several groups of drones from different directions and fired 28 cruise missiles from its Tu-95MS bombers. Although all were intercepted by Ukrainian air defense, fragments still rained down on the city, causing destruction, fire and death.

Physical traces of death and destruction are everywhere in Ukraine, including in Lviv. But it was in people’s stories of loss and grief and their spirit, pride, and hope that, for me, the war manifested most intensely. Yevhenia, who drove me both in and out of Ukraine, spoke to me of her 13-year-old son who, during my stay, had his first day at the national army academy. She proudly showed me a video of his freshman cohort in military uniform marching past the crowd to the sound of a brass band, the sadness of leaving her little boy there to only come home one in every four weekends clearly visible, too. A participant at one of the training workshops showed me a picture of her son and told me how he, who had been studying law at the start of the war, stepped up to defend Antonov airport in Kyiv with his peers when Russia invaded. Only 22, he is already a veteran at the front. Valentyna told me how her apartment had been hit by a missile and that, now, whenever there is an air raid, she comforts her frazzled cat by distracting him with Tom & Jerry videos.

As a leaving present, Kateryna gave me a beautiful picture book from Lviv in which she left little notes by all the places we had visited together, such as the Jesuit church of saints Peter and Paul, where Lviv says goodbye to its fallen soldiers in near-daily services. There are still many more places to visit in Lviv, she said, adding that she looks forward to introducing them to me, along with other cities in Ukraine, “including those currently under temporary occupation that will become rebuilt and free in the future.” For sure I will be back in this impressive country.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Ukraine, public health

Topics: Biosecurity