WHO member states are negotiating a pandemic treaty. But will countries follow the new rules?

By Elliot Hannon, Nina Schwalbe , Susanna Lehtimaki | February 15, 2024

The World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters. Credit: ©Yann Forget / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA.

The World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters. Credit: ©Yann Forget / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA.

The outbreak of COVID-19 and its evolution into a full-blown pandemic showed the importance of coordinated action in stopping the spread of a virus, as it also showed the importance of acting quickly and decisively before cases spread far and wide. The global response to the pandemic, however, revealed serious deficits in how the global community prepares for and responds to outbreaks, a failure that has cost millions of lives and trillions of dollars.

To improve the world’s collective pandemic efforts, the World Health Assembly (WHA), the 194-member state body that oversees the work of the World Health Organization (WHO), voted in December 2021 to start negotiations on a new pandemic accord. The assembly laid out an ambitious timeline, giving negotiators until May 2024 to present a new global pact.

When the negotiations first began, the world was still mired in the pandemic, creating a sense of urgency and optimism that stronger commitments, greater authority, increased accountability, and dedicated resources could be had. The aim was to create a new set of state commitments, improving a number of key areas: building resilient national health systems as a first line of defense, strengthening surveillance measures to quickly detect outbreaks, and enhancing equitable access to pandemic countermeasures such as vaccines, among other issues.

The negotiations have revolved around these issues, but remarkably little attention has been paid to state compliance and implementation of the accord. No matter how these larger differences get resolved, other existing international treaties have shown that without greater accountability to generate compliance with the agreement, the best intentions of the pact won’t matter. The response to COVID-19 laid bare that reality: Signing an accord, even one that is legally binding, does not mean that countries will implement it.

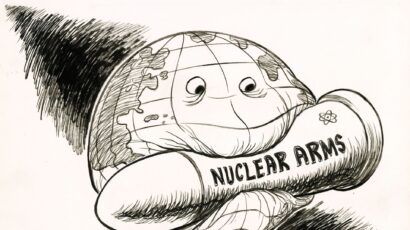

Some form of an independent monitoring mechanism is essential, and there are models from treaties in other areas, from atomic energy to chemical weapons, that can help inform how a new pandemic accord will keep its signatories in line. It seems unlikely that the pandemic treaty can include on-site inspection authority, but an authoritative monitor able to call out states for noncompliance is key to the treaty’s effective implementation.

Possible models for an international public health monitor. As negotiations have gone on, the immediate impact of the pandemic has receded and the political will to make tough compromises has also faded. Russia’s war in Ukraine and global economic crisis brought the pandemic-era moment of common cause to a close, jumpstarting old geopolitical rivalries. The lost momentum led WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus to warn in late January that the risk of talks falling apart altogether was real.

By contrast, it took just six months following the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986, for diplomats to negotiate the Convention on Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident, states to sign it, and the treaty to enter into force. The moment to achieve that level of consensus in driving sweeping reforms to pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response may have passed. That’s why it’s essential that this pandemic accord specifically addresses accountability and compliance—to make sure the reforms that are achieved punch their weight.

Early drafts of the accord did include some text on peer review and self-reporting, as well as for the main governing body, the “Conference of the Parties,” (COP), to raise an implementation and compliance committee. Similar to the body that governs the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and attracts significant attention, the accord’s governing body will comprise delegates representing state parties and meet regularly to oversee the implementation of the accord. However, the language on compliance in the drafts has been weak and noncommittal, and it is unclear whether these references, in particular regarding compliance, will survive in the text or be left for later negotiation, as an addendum to the accord.

The concept of a legally binding global agreement in the case of a public health emergency is not new. In 1969, the World Health Assembly adopted the International Health Regulations (IHR), the agreement that governs state preparedness and response to public health emergencies. After a 2005 revision, countries are once again revisiting the regulations, an amendment process that is taking place concurrently with the pandemic accord negotiations. However, as the experience of COVID-19 made clear, the regulations lack any independent accountability mechanism to make states meet their obligations for compliance as they rely solely on states self-reporting or voluntary evaluations, similar to the compliance measures that have been proposed in current pandemic accord negotiations. Experience with the International Health Regulations and other agreements—treaties of all kinds—has shown that that is not sufficient. State self-reporting and peer review are important—but not enough. They can be unreliable—state reports are often late, incomplete, or inaccurate, and political factors influence peer reporting.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is perhaps the leading example as it conducts ongoing monitoring of state reporting as part of the agency’s safeguard system to verify state compliance with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The IAEA is empowered to deploy independent inspectors to make in-country visits to verify a state’s reporting, as well as make routine inspections to nuclear sites that can be announced, unannounced, or on short notice. This serves as a confidence-building measure, an early warning mechanism, and a trigger to heighten responses. In addition, the agency also has complementary inspection authority, giving expanded access to information and sites, such as the use of satellite systems to monitor sites.

This sort of investigative authority is foreign to the two existing public health agreements, the International Health Regulations and the Framework Convention on Tobacco, as WHO´s engagement with the member states takes place on a voluntary basis. The International Health Regulations read as more of a “how to guide,” outlining requirements for states to develop core public health capacities to better prepare for and respond to public health emergencies that could potentially impact international traffic and trade. It also lays out protocols for what happens after an outbreak is detected, depending on whether it rises to the level of international concern, and defines the role of WHO in preparedness and response. But there is no accountability for noncompliance.

The regulations do not currently grant the WHO any explicit investigative power, either in the preparation stage or in response to a pandemic. And unlike nuclear agreements, WHO officially relies on state self-reporting. Any in-country visits or investigations are collaborative, conducted only at the state’s request, and typically geared towards providing technical assistance to the host country. As was seen in the earliest moments of COVID-19, in-country visits can be a highly political process. China initially refused admission to inspectors to early outbreak sites in Wuhan. When China did finally allow an international team into the country, their physical access was restricted, as was access to crucial data.

How a public health monitoring authority could work. While emergency on-site investigative authority would be meaningful, these are currently a non-starter for the pandemic accord. WHO member states have shown little appetite for ceding sovereignty to improve enforcement. The “big powers,” including the United States and other high-income countries, have made clear that they would be unwilling to participate in an agreement that opened them up to mandatory investigation.

Compliance, however, is key.

There are other mechanisms borrowing from the IAEA system that could make a difference. An independent monitoring body as part of the accord could serve a similar function of the IAEA safeguard system in building confidence in the agreement, as well as acting as an early warning system for noncompliance that triggers a response. Rather than a negotiation afterthought, such a body would need to be enshrined in the text of the accord from the get-go. It would need specific authority to verify the timeliness, completeness, and accuracy of states’ reports.

To be successful, the monitoring body would need to have technical, operational and organizational, political, and financial independence to conduct impartial review of state reporting. It would review state governments’ self-reports on compliance, as well as seek out additional information from non-state sources, such as civil society and global organizations. To avoid duplication of other efforts, including the International Health Regulations and the WHO Emergencies Programme, and to make the monitoring body more politically palatable, it would have a mandate limited to assessing state reporting and compliance with their treaty obligations.

While independent on-site investigative authority may not be possible now, an independent monitoring body that has the authority to access information independently, from multiple sources, and to call out states for noncompliance can make a crucial difference in states complying with an agreement. Independent monitoring is feasible, viable, and achievable, making it essential to preparing for and responding to the inevitable next pandemic.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: COVID-19, WHO

Topics: Biosecurity

Thaks for a very insightful and rightfully critical article on the Pandemic Accord – or Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response treaty, as it used to be called. But a great shame you skipped the more important failings – the absence of anything related to prevention, mitigation, airborne transmission etc. of crucial importance to Covid19, or any new pandemic pathogen. THIS is the more serious and substantial failing of the negotiations. Without which, we are condemed to ongoing unbridled transmission, deaths and disability from what is emerging as a very serious and debilitating pathogen. See collated evidence here: http://www.c19.life WHO, member… Read more »