OpenAI’s new text-to-video app is impressive, at first sight. But those physics glitches…

By Gary Marcus | February 16, 2024

Photo by Andrew Neel on Unsplash

Photo by Andrew Neel on Unsplash

Editor’s note: This piece originally appeared in the substack newsletter “Marcus on AI” and is published here with permission.

The tech world is abuzz with OpenAI’s just-released latest text-video synthesizer, and rightly so: It is both amazing and terrifying, in many ways the apotheosis of the AI world to which they and others have been building. Few if any people outside the company have tried it yet (always a warning sign), so everyone else is left with the cherry-picked videos OpenAI has cared to show. But even from the small number of videos out, I think we can conclude several things.

- The quality of the videos is spectacular. Many are cinematic; all are high-resolution, and most look as if (with an important asterisk I will get to) they could be real (unless perhaps you watch in slow-motion). Cameras pan and zoom, and nothing initially appears to be synthetic. All eight minutes of known footage are here and certainly worth watching for at least a minute or two.

OpenAI (despite its name) has been characteristically close-lipped about what they have trained the models on. Many people have speculated that there’s probably a lot of stuff in there that is generated from game engines like Unreal. I would not at all be surprised if there also had been significant training using YouTube and various other outlets containing copyrighted materials. The work of artists have presumably been used without permission or compensation. I wrote a few words about this yesterday on X, amplifying the thoughts of fellow AI activist Ed Newton-Rex. He, like me, has worked extensively on AI and increasingly become worried about how the technology is being used in the world.

- The uses for the merchants of disinformation and propaganda are legion. Look out 2024 elections.

- All that’s probably obvious. Here’s something less obvious: OpenAI wants us to believe that this is a “path towards building general purpose simulations of the physical world.” As it turns out, that’s either hype or confused, as I will explain below.

Others seem to see these new results as tantamount to artificial general intelligence (AGI), systems whose cognitive capabilities rival those of humans’ and vindication for scaling laws, according to which AGI would emerge simply from having enough compute and big enough datasets.

In my view, these claims—about AGI and world models—are hyperbolic, and unlikely to be true. To see why, let’s take a closer look.

Watching the (small number of available) videos reveals lots of odd occurrences—things that couldn’t (or probably couldn’t) happen in their real world. Some are minor; others reveal something deeply amiss.

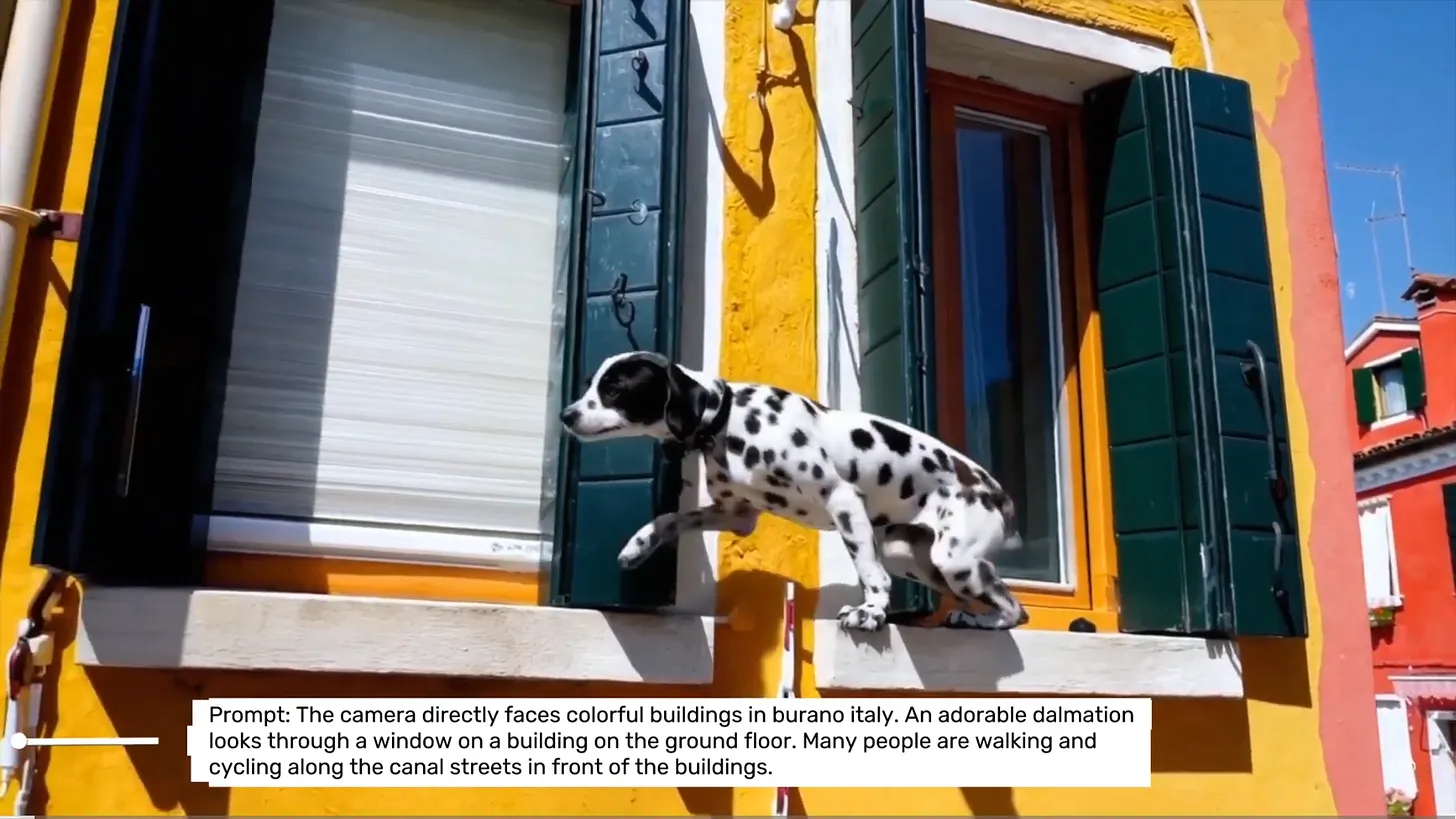

Here’s a minor example. Could a dog really make these leaps? I am not convinced that is either behaviorally or physically plausible. (Would the dalmatian really make it around that wooden shutter?) It might pass muster in a movie; I doubt it could happen in reality.

Physical motion is also not quite right, almost zombie-like, as one friend put it:

Causality is not correct here, if you watch the video, because all of the flying is backwards.

Careful examination of this one reveals a boot where the wing should meet the body, which makes no biomechanical or biological sense. (This might seem a bit nitpicky, but remember, there are only a handful of videos so far available, and internet sleuths have already found a lot of glitches like these.)

There are lots of strange acts of defying gravity if you watch closely, too, like this mysteriously levitating chair (that also shifts shape in bizarre ways).

Full video for that one can be seen here. It’s worth watching repeatedly and in slow motion, because several weird things happens there.

What really caught my attention though in that video is what happens when the guy in the tan shirt walks behind the guy in the blue shirt, and the camera pans around. The tan shirt guy simply disappears—so much for spatiotemporal continuity and object permanence. Per the work of Elizabeth Spelke and Renee Baillargeon, children may be born with object permanence, and certainly have some control over it by the time they are 4 or 5 months old; Sora is never really getting it, even with mountains and mountains of data.

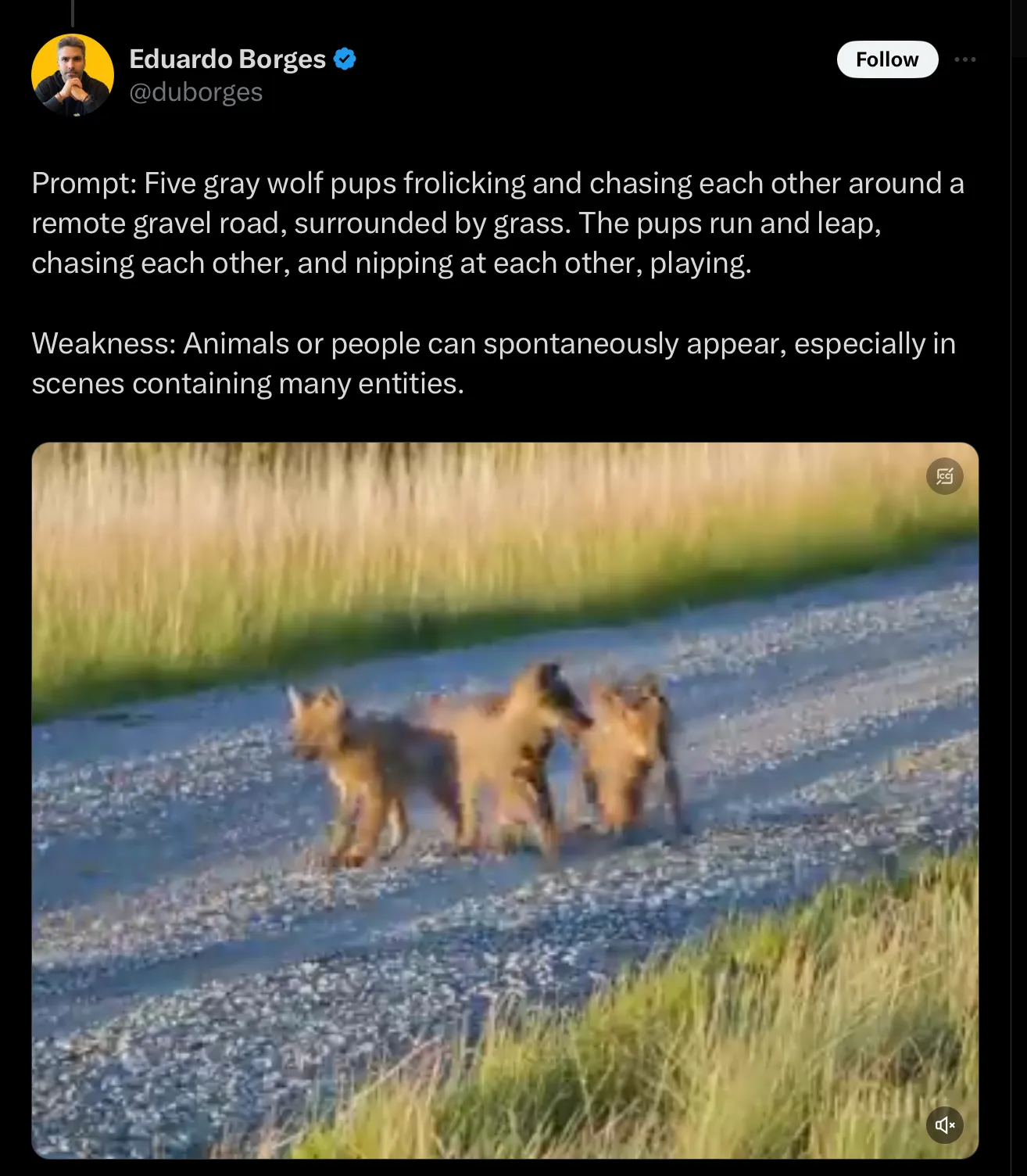

That gross violation of spatiotemporal continuity or failure of object permanence is not a one-off, either. In shows up again in this video of wolf-pups, which wink in an and out of existence.

As Jurgen Gravestein pointed out to me, it’s not just animals that can magically appear and disappear. For example, in the construction video (about one minute into the compilation above), a tilt-shift vehicle drives directly over some pipes that initially appear to take up virtually no vertical space. A few seconds later, the pipes are clearly stacked several feet high in the air; no way could the tilt-shift drive straight over those.

There will be, I am certain, more systemic glitches as more people have access.

And importantly, I predict that many of these glitches will be hard to remedy. Why? Because the glitches don’t stem from the data, they stem from a flaw in how the system reconstructs reality. One of the most fascinating things about Sora’s weird physics glitches is that most of these are not things that appear in the data. Rather, these glitches are in some ways akin to large language model “hallucinations,” artifacts from (roughly speaking) data decompression, also known as lossy compression. They don’t derive from the world.

More data won’t solve that problem. And like other generative AI systems, there is no way to encode (and guarantee) constraints like “be truthful” or “obey the laws of physics” or “don’t just invent (or eliminate) objects.”

Space, time, and causality would be central to any serious world model. My book about AI with Ernest Davis was about little else; those were also central to Kant’s arguments for innateness, and have been central for years to Elizabeth Spelke’s work on “core knowledge” in cognitive development.

Sora is not a solution to AI’s longstanding woes with space, time, and causality. If a system can’t handle the permanence of objects, I am not sure we should even call it a world model at all. After all, the most central element of a model of the world is stable representations of the enduring entities therein, and the capacity to reason over those entities. Sora can only fake that by predicting images, but all the glitches show the limitation of such fakery.

Sora is fantastic, but it is akin to morphing and splicing, rather than a path to the physical reasoning we would need for artificial general intelligence. It is a model of how images change over time, not a model of what entities do in the world.

As a technology for video artists that’s fine, if they choose to use it; the occasional surrealism may even be an advantage for some purposes (like music videos). As a solution to artificial general intelligence, though, I see it as a distraction.

And God save us from the deluge of deepfakery that is to come.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: AI, OpenAI, Sora, artificial intelligence, generative AI

Topics: Artificial Intelligence, Disruptive Technologies

FYI, “tilt-shift” is a camera technique using a special lens that results in the strange perspective seen in the video, not a type of vehicle.