Above: Mayor of Paris Anne Hidalgo is seen swimming in the river Seine on July 17, 2024 in Paris, France. The city's mayor took a dip in the Seine amid concerns over water cleanliness ahead of the Olympic Games, in which the river will host triathlon and marathon swimming events. (Photo by Pierre Suu/Getty Images)

Editor's note: The men's triathlon event, originally scheduled for the morning of July 30th, was postponed due to unsafe levels of pollution in the Seine. Organizers announced that the event would instead be held on July 31st, following the women's triathlon.

With the Olympics set to kick off, the eyes of the world turn to Paris and the young athletes who’ve trained for years for a chance to compete for their country. But perhaps the most talked about topic heading into the Olympics is not an athlete—it’s a river. When Paris was selected to host the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Summer Games, organizers set about an ambitious plan to host several events in the notoriously dirty River Seine that runs through the heart of the city, requiring a massive cleanup effort. Seven years later, only days away from the events, there is still some uncertainty about whether this expensive project will succeed.

The project serves several purposes. It revives a cultural legacy that the French seek to showcase during their turn in the Olympic spotlight. But it is also a climate change adaptation strategy. As temperatures continue to climb, many in the city are expected to look to the river as a cheap and quick means to cool down in the heat. If the cleanup effort is successful, the river will open to public swimming in 2025 for the first time in over 100 years, providing much-needed relief for Parisians.

Swimming in the Seine has been banned since 1923 because of pollution and boats, but it had been a popular activity in the French capital in the 17th century, when men and women would bath nude, separated by canvas cloths. In the 18th century, bathhouses and pools emerged and swimwear became required. Diving competitions were held in the river not long before swimming was outlawed.

Since that time, many French politicians have vowed to clean up the Seine, without success. Former Paris mayor Jacques Chirac vowed to bathe in the Seine to prove its cleanliness in 1988, but that splash never came to pass. Last Wednesday, Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo finally followed through on that promise, dipping into the river to vouch for its safety. Still, even now, Olympic organizers are aware that some events could be postponed or canceled without favorable weather, and the cleanup of the river can still be called into doubt.

Over the past year, several test events had to be canceled owing to high levels of pollution—specifically, E.coli, a potentially deadly bacteria found in human waste. City officials maintain that there is no option to host the triathlon or marathon swimming events elsewhere.

The story of the Seine is not dissimilar from the fates of many urban rivers around the world. As countries industrialized and populations in cities exploded, urban waterways became a cheap means of getting rid of both residential and industrial sewage, a process that rendered many urban waterways unthinkable for swimming or other activities. With efforts underway around the world to reclaim urban waterways for city dwellers, the Seine cleanup could provide hope for other cities looking to renew their own rivers—or a warning about how difficult it is to bring a river back to life in the modern, warming world.

A mandate to change.

Last month, the British Association for Sustainable Sport published a report that noted the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the hottest Olympics in history, “offered a window into an alarming, escalating norm for Summer Olympics.” In Tokyo, temperatures soared to 93 degrees Fahrenheit and 70 percent humidity. Some athletes vomited after crossing the finish line in the triathlon, and wheelchairs were supplied to carry others off tennis courts.

This year, the Paris Olympics will take place in high summer, around the same time of year as the 2003 heat wave that killed more than 14,000 people across France, and there is a distinct possibility that the Paris Olympics will exceed the heat of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. In major cities like Paris, extreme heat is exacerbated by the “urban heat island” effect, by which a lack of trees and vegetation increases temperatures.

Despite the threat posed by heat, officials have built the Olympic Village without air conditioning, in a bid to make this the first carbon-neutral Olympics in history. Instead of AC and its associated carbon emissions, the organizers have opted for an underground water cooling system below the Olympic Village.

It's a novel system that exemplifies the challenge of adapting to climate change without exacerbating it. The highly touted cleanup of the River Seine is another piece of that complicated puzzle, particularly after the Olympics are over, when officials aim to open the river to public swimming once again.

Europe is the fastest-warming continent on the planet, with fewer than 20 percent of European households owning air conditioners to deal with the rising temperatures, compared to nearly 90 percent in the United States. Even with large-scale investments to reduce worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, some temperature increase is unavoidable. Jake Madelone of the Waterfront Alliance, a nonprofit focused on restoring and developing waterfront areas in New York, has called swimming in local waters a “no-brainer” climate change adaptation.

New York’s infrastructure makes the city 9.7 degrees hotter than it would otherwise be—and it’s likely to get worse. “The temperature is only going to get hotter on the East Coast—it's just going to get more and more humid,” Madelone explained. “Being able to jump into the water, that's a huge way to mitigate things like getting heat stroke or heat exhaustion, or, frankly, even passing out and possibly dying from the increased heat.”

In other words, having a body of water available to cool the population en masse is a common good and a public health measure. Rivers in other major European cities—including Copenhagen, Berlin, Zurich, Munich, and Vienna—are spotted with swimmers in the summer. What makes Paris different is the high-profile showcase that the Olympics provide. A lot of other major cities will be taking notes.

Rivers around the world need help.

Major rivers around the world have fostered the growth and development of large cities and nurtured growing human civilizations. For thousands of years, the Nile and the Tigris-Euphrates River system supported enormous populations that relied on the waterways for survival—encouraging trade, industrialization, and waste management. Rivers have always been a means for waste and pollution removal, but the scale has changed drastically. As cities began to industrialize in the 18th century, rivers were altered to better accommodate industry, shipping, and waste management.

Today, the Nile basin has been polluted by heavy metals, microplastics, and other contaminants beyond the World Health Organization’s safety guidelines. The Tigris-Euphrates basin has become a dumping ground for wastewater—often untreated—which has led to outbreaks of cholera for those who have no choice but to rely on the river for drinking water.

It’s a familiar sight around the world.

The Ganges, which supports 10 percent of the global population and flows through 50 major cities in India alone, is one of the most polluted rivers in the world, with high levels of untreated sewage and toxic waste.

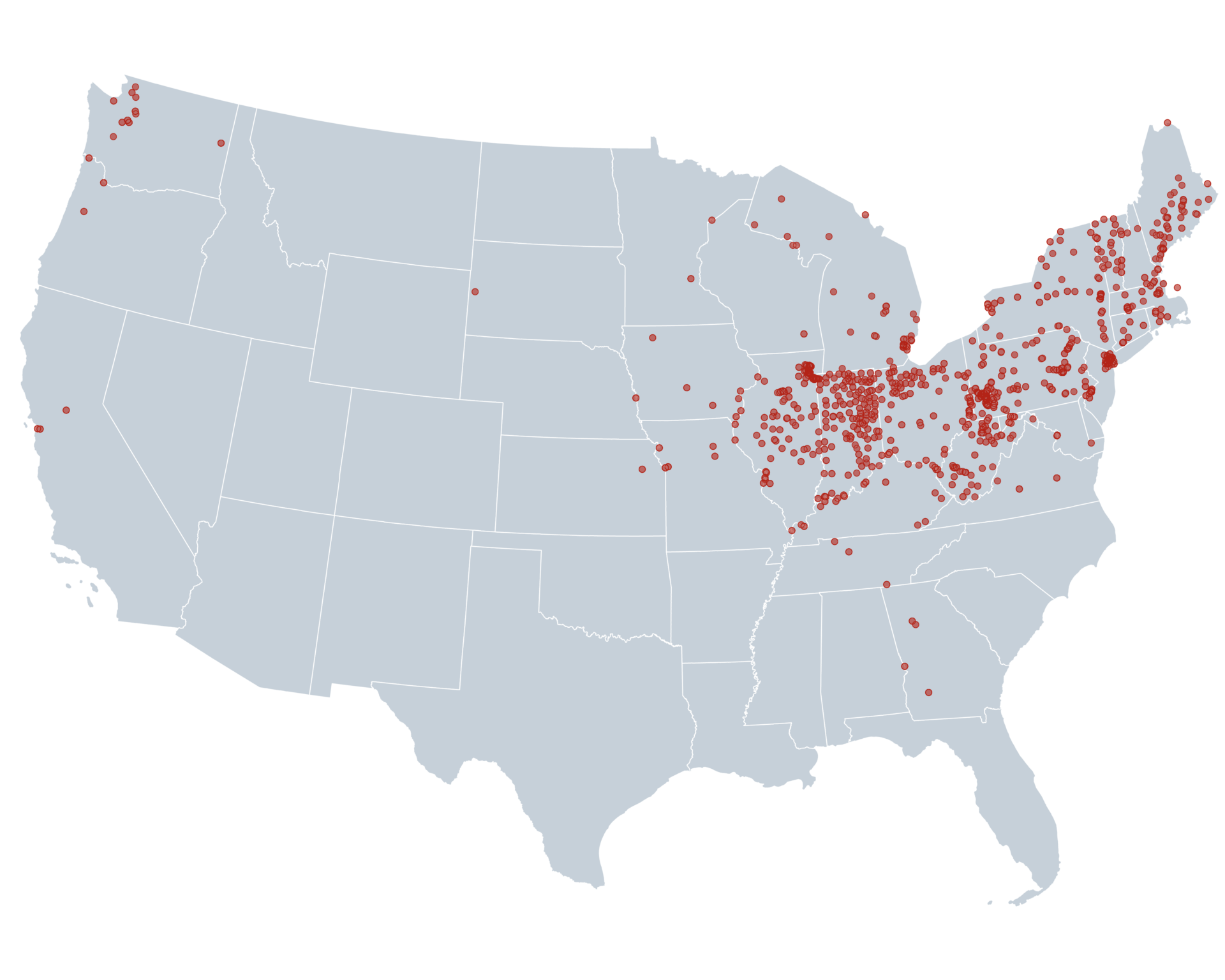

A 2022 report from the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP), a nonprofit that advocates for effective enforcement of environmental laws, found that 51 percent of rivers across the United States, accounting for 700,000 miles of waterways are too polluted for swimming, fishing, or drinking.

Overall, a UN study in 2021 found that 3 billion people are at risk because of the water quality in their local water supply is unknown. Further, 2.3 billion people are living in “water-stressed” countries without enough freshwater supply to meet demand.

What makes a river dirty?

Researchers look at several different indicators to approximate the health of a river. In Paris, recent testing of the river has shown high levels of E. coli, which is considered an “indicator organism” that appears when fecal matter is present in water. Most forms of E. coli are harmless, but certain strains can lead to serious illness. Swimming in water contaminated with E. coli can cause gastrointestinal illnesses or infections, often with symptoms like vomiting, cramps, fever, or bloody or watery diarrhea. For organizers, it has been particularly challenging to guarantee safe levels of E. coli after a storm.

Paris employs a combined sewer system that transports sewage and runoff from storm drains together to a treatment facility. Water treatment facilities are available to treat water from around a city daily, but like all infrastructure elements, they have a limited capacity. During heavy storms, a combined system will allow untreated waste and stormwater to flow through an outlet into a body of water, like the Seine, to avoid overwhelming the treatment plant. This is known as a combined sewer outflow (CSO) and is what the EPA defines as “point” pollution, meaning the pollution is coming from a single source.

Modern sewage systems separate wastewater and stormwater in different pipes, but many older cities in the United States and around the world still use combined sewer systems. The EPA keeps tabs on the roughly 700 US communities with CSOs, primarily around the Northeast and the Great Lakes. “We're dealing with a very old sewer system,” Madelone says about New York’s combined sewer system. “Frankly, after every rainstorm, we're just getting more and more E. coli getting into the water.”

Paris is attempting to overcome this issue by building a gigantic water basin, called Austerlitz, which can hold 13.2 million gallons of water. Ideally, this basin will hold runoff until it can be treated, then released back into the Seine.

In some ways, this is the easy part, and it’s what the organizers have targeted to ensure the water levels are safe on the day of the competition. The water that gets channeled into the river can be cleaned because it’s easily identified—but what about the pollution that’s already in the river?

That’s the harder part.

The convergence of many forms of pollution together is called “nonpoint” pollution and it can happen hundreds of miles away from the area of concern. PIREN-Seine, a 30-year study of the Seine, found chemicals from the burning of fossil fuels called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, as well as plastics, antibiotics, flame retardants, and pesticides throughout the Seine River Basin. Antibiotics find their way into waterways through agriculture and livestock rearing and can be particularly worrisome because they can promote antibiotic resistance in the wild.

According to the Mississippi Watershed Management Organization, during winter, many roads within that enormous watershed are treated with salt to manage snow and ice accumulation; after the treated snow and ice melt, the resulting runoff leads to river pollution and affects fish and plant populations.

Another source of non-point pollution is nutrient pollution. This is when excess quantities of fertilizer chemicals like phosphorous and nitrogen flow into waterways. They can lead to an overgrowth of algae, which can hog oxygen and kill plants and aquatic animals. This is the primary cause of the Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone, an area of more than six thousand square miles at the end of the Mississippi River where low oxygen levels can kill marine life at and near the bottom of the ocean.

The WHO has established water quality standards that can be applied across national circumstances. The problem is many nations lack the institutional capacity to implement those changes or haven’t received enough of a popular mandate to implement them. In some cities, basic water, sanitation, and hygiene facilities are lacking, and open defecation leads to high levels of E. coli in the water.

Cleaning up point pollution is relatively straightforward; governments can make improvements to sewage systems and water treatment facilities locally. But nonpoint pollution requires regional action, which is usually more expensive and politically difficult.

While efforts are underway around the world to improve river health—in places like Portland, Chicago, and Washington, DC in the US—progress can be very slow. Success won’t look the same everywhere.

A tale of two rivers.

While there has been some level of effort to clean up the Seine for decades, in Los Angeles, the host city for the 2028 Olympic Summer Games, it’s taken significant effort to acknowledge that its local river even exists. Winding through concrete riverbeds from the San Fernando Valley and draining into the Pacific Ocean around Long Beach, the LA River is better known as a Hollywood shooting location than a waterway.

The LA River is alluvial—dry in the summer and flooded in the winter—with water flow spread across a large flood plain. As the population of Los Angeles grew, the river was channeled to make space for development. This proved catastrophic when heavy floods in the 1930s destroyed multiple bridges and thousands of homes and businesses. The Army Corps of Engineers encased the entire river in concrete as a flood-control measure.

Left: The first aerial photo of Los Angeles, taken by Edwin H. Husher in 1887, showing the LA River passing through a city of, then, 20 thousand people. Right: An aerial approximation from Google Maps showing the modern version of the LA River winding through a city of nearly four million people.

A 2006 Supreme Court decision began requiring proof of a “significant nexus” between wetlands and “navigable-in-fact” waterways to constitute protections under the Clean Water Act. The decision undermined the LA River’s eligibility for protection and meant it could remain a ditch, not subject to the same regulation as other rivers.

To protest the decision, a group of kayakers led by George Wolfe, the editor of the satirical LaLaTimes website, traversed the roughly 50-mile LA River for three days from the San Fernando Valley to the beach. Two years later, in 2010, the EPA took control of the LA River from the Army Corps of Engineers, confirming its status as a “traditional navigable water” and citing the “current conditions of flow and depth to support navigation by watercraft.” According to Wolfe, the kayaking protest spurred the EPA to action, and there has been significant progress in cleaning up the river since then.

The LA River Master Plan is an encyclopedic vision to revitalize 51 miles of the waterway by constructing parks, bike paths, and restoring habitats for birds and other wildlife. Much like the Seine, these projects serve a climate adaptation function. The projects listed in the plan can help reduce the urban heat island effect around the concrete riverbed, which makes the communities closest to the river especially vulnerable to climate change, particularly south of downtown Los Angeles.

Removing the concrete floor of the river, allowing plants and wetlands to grow and absorb water to recharge underground aquifers, won’t work because of the intensity of seasonal flooding and dense urbanization throughout Los Angeles. Slowing the flow of water through the channel might cause it to overflow into neighboring suburbs, likely requiring the relocation of large numbers of residents, many of them poor.

That realization led the famed architect, Frank Gehry, to suggest building parks above the river, creating a mile-long green bridge across the channel. The platform parks remain hypothetical and somewhat controversial because of their high cost, but other park elements are already under construction. Still, building above the river is a highly innovative solution demonstrating how conceptions around the purpose and possibilities of the river are being challenged.

“The river is not just about that concrete channel in the river,” Jon Christensen, a professor at the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA, told me. “It has a huge place in the imagination of people in Los Angeles.”

Is it worth it?

The cleanup of the Seine is expected to cost around $1.5 billion—a hefty price tag—and some may disagree on whether the results are worth that kind of investment. Such cost-benefit calculations are particularly tricky because a river doesn’t have a price tag on it. Economists rely on “non-market valuations” to establish the value that people give to environmental goods, but these valuations rely heavily on assumptions.

In a 2018 study, economists from Iowa State University, Cornell University, and the University of California, Berkeley estimated that the US government had spent more than $1.9 trillion (in 2014 dollars) since 1960 to reduce pollution in rivers and lakes throughout the United States. Was it worth it? It depends on who you ask.

Twenty different cost-benefit analyses from the 1960s to 2015 found that the benefits of those investments reached only about half of their costs. In other words, “they have negative net benefits.” The authors were surprised by this but pointed out that those analyses had a narrow framework for calculating benefits. Many such analyses, they argue, don’t include significant health benefits like cleaner drinking water or the willingness to pay for the existence of clean ecosystems because it’s pleasant or pretty (known as “existence values”). To grasp the full value of river cleanups, it’s necessary to expand the understanding of the benefits that they provide.

Catherine Kling, one of the economists who wrote the study, has argued that there are hard economic reasons to invest in restoring rivers. Investing in river cleanups can raise property values, incentivize businesses to open near the waterfront, and “most importantly, [improve] quality of life for residents and visitors,” Kling writes. “Enhancing green spaces in the face of a rapidly changing climate is an economically sound adaptation strategy.”

Some river cleanup efforts have been so successful, in fact, that they’ve been accused of creating a “green gentrification cycle,” in which investment in green spaces drives up property values and pushes out disadvantaged communities. A study at the University of Utah found that gentrification often “precedes” green investment in places like Chicago that are already fairly green, meaning that many areas are already gentrifying when green investment projects are announced. In Los Angeles, however, they found that gentrification “precedes and follows” green investment because there is such high demand to be near a park or green space. The authors suggest that policymakers focus on greening the most disadvantaged areas, and couple that with the construction of affordable housing.

People are eager to replicate solutions that work, which is why the River Seine will be watched so closely. “I know that there's been a lot of concern of whether or not it's going to be ready for the Olympics,” the New York Waterfront Alliance’s Madelone says. “I think if they're able to pull this off and get the Seine to be actually accessible and swimmable, I think that could serve as a great model for New York and for other cities.”

Fight for your right to the city.

It’s relatively common to see Europeans swimming and lounging along the banks of their urban waterways and lakes. For many in the United States, the possibility of swimming in an urban river seems a foreign concept. Paul Hockenos wrote in the New York Times in 2023 about swimming in the Isar River in Munich. “Clusters of students, off-duty office workers, families, and nude sunbathers were sprawled out on blankets with bottled beer and light meals.” The sight made him “quiver with envy.”

The ways that river cleanups manifest will vary. New York is installing a filtered pool that will float in the East River, so starting in 2025, New Yorkers should be able to swim beneath the city’s skyline. The Anacostia Riverkeeper group is hoping to host a swimming event this summer in a part of Anacostia River alongside the District of Columbia, for the first time since 1971, when swimming in district waters was banned. This fall, the Chicago River, once so dirty its flow direction was reversed, so its water wouldn’t enter and pollute Lake Michigan, may host swimmers for the first time in a century—though the location of the swim remains uncertain.

In some stretches, the LA River is now clean enough and deep enough for kayaking tourism, but swimming remains an elusive activity because of high levels of pollution. I asked Christensen about swimming in the LA River, and whether some sections would ever be clean enough to swim in. “I do actually think that's a great aspirational vision,” he said. “That we could swim sometime in the LA River, I think [it’s] a vision that we should aspire to realize, and I think it's achievable.” But please don't try to swim there during the winter.

Restoring urban rivers has required, and will continue to require, a combination of political will, public pressure, and a common understanding of the value that such spaces provide. For Olympic organizers, after seven years and $1.5 billion, the moment of truth is almost here. Heavy rain in June led to levels of E. coli 10 times higher than the safe limit, but a sunnier and less rainy July allowed for Mayor Hidalgo’s swim. At least two other swimmers tested the water earlier this month: an American journalist and the French sports minister. Officials seem hopeful but have acknowledged that events could be delayed or even canceled if the water isn’t clean enough on race day. Paris is aiming to show the world that it’s possible to clean up a river that’s been polluted for more than a century. At this year’s Olympics, perhaps everyone should be rooting for the Seine.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Los Angeles, anacostia, ganges, new york, olympics, paris, rivers, seine, tigris-euphrates, urban waterways

Topics: Climate Change, Multimedia