Let’s review the messages in our 2004 paper in Science. The paper assumes that the world wishes to act decisively and coherently to deal with climate change. It makes the case that “humanity already possesses the fundamental scientific, technical and industrial know-how to solve the carbon and climate problem for the next half-century.” This core message surprised many people, because our paper arrived at a time when the Bush administration was asserting that, unfortunately, the tools available were not suited for addressing climate change. Indeed, at a conference I attended at that time, Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham insisted that a discovery akin to the discovery of electricity was required.

Our focus on “the next half century” was novel; the favored horizon at the time was a full century — and still is. We argued that “the next fifty years is a sensible horizon from several perspectives. It is the length of a career, the lifetime of a power plant, and an interval whose technology is close enough to envision.”

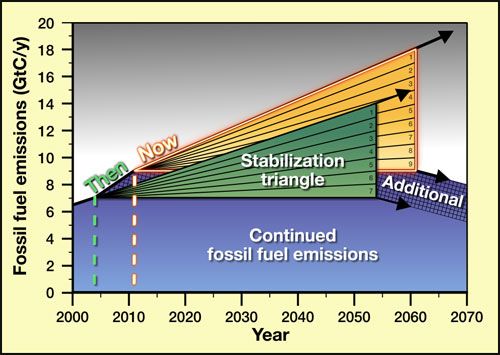

In a widely reproduced Figure (see below) we identified a Stabilization Triangle, bounded by two 50-year paths. Along the upper path, the world ignores climate change for 50 years and the global emissions rate for greenhouse gases doubles. Along the lower path, with extremely hard work, the rate remains constant. We reported that starting along the flat emissions path in 2004 was consistent with “beating doubling,” i.e., capping the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration at below twice its “pre-industrial” concentration (the concentration a few centuries ago).

The 2004 “wedges” paper assumed that the objective of global mitigation would require a flat emissions rate for 50 years, followed by a falling rate. Making the same heroic assumption today would result in substantial additional emissions. Illustration by Climate Central.

The paper is probably best known for having introduced the “stabilization wedges,” a quantitative way to measure the level of effort associated with a mitigation strategy: a wedge of vehicle fuel efficiency, a wedge of wind power, and a wedge of avoided deforestation have the same effect on carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Filling the stabilization triangle required seven wedges. The wedge concept fosters parallel discussion of alternatives and encourages the design of a portfolio of responses. Each wedge is an immense activity. In talks about this work, I like to say that we decomposed a heroic challenge into a limited set of monumental tasks.

In short, in addition to a hopeful message that humanity is not helpless, the paper contains the sobering message that the job ahead is daunting.

Today, nine wedges are required to fill the stabilization triangle, instead of seven. A two-segment global carbon-dioxide emissions trajectory that starts now instead of seven years ago — flat for 50 years, then falling nearly to zero over the following 50 years — adds another 50 parts per million to the equilibrium concentration. The delayed trajectory produces nearly half a degree Celsius (three-quarters of a degree Fahrenheit) of extra rise in the average surface temperature of the Earth. (Note that there is a three-year lag in the posting of authoritative global data. We used 2001 data in our 2004 paper, and 2008 data are available now. Thus, available data do not yet reflect the recession. Between 2001 and 2008, the emissions rate climbed by more than a quarter.)

Worldwide, policymakers are scuttling away from commitments to regulations and market mechanisms that are tough enough to produce the necessary streams of investments. Given that delay brings the potential for much additional damage, what is standing in the way of action?

Familiar answers include the recent recession, the political influence of the fossil fuel industries, and economic development imperatives in countries undergoing industrialization. But, I submit, advocates for prompt action, of whom I am one, also bear responsibility for the poor quality of the discussion and the lack of momentum. Over the past seven years, I wish we had been more forthcoming with three messages: We should have conceded, prominently, that the news about climate change is unwelcome, that today’s climate science is incomplete, and that every “solution” carries risk. I don’t know for sure that such candor would have produced a less polarized public discourse. But I bet it would have. Our audiences would have been reassured that we and they are on the same team — that we are not holding anything back and have the same hopes and fears.

It is not too late to bring these messages forward.

Unwelcome news. Environmental science has brought unwelcome news — that the actions of our species are capable of changing the planet at global scale. Who wouldn’t much rather live on a larger planet, where our actions mattered less? It is counterproductive for advocates of prompt action on climate change to pretend that the new knowledge has only positive consequences, such as the stimulation of green jobs and elegant new technology. Global prosperity now depends on our species’ success at a totally unfamiliar assignment: to “fit” our many billions of people on this small planet, with its finite resources and finite capacity to withstand pollution. The job will be very hard and will require sustained focus.

Confronted with unwelcome news, human beings often shoot the messenger. Consider two earlier occasions. Galileo argued that the Earth wasn’t at the center of the universe. For this, he was excommunicated. Darwin argued that human beings were part of the animal kingdom, and he was cruelly mocked. The idea that humans can’t change our planet is as out-of-date and wrong as the Earth-centered universe and the separate creation of Man, but all three ideas have such appeal that they will fade away only very slowly.

In particular, just as steadily stronger evidence for the Copernican model and for evolution only gradually won the day, we should anticipate robust resistance to the message that we are fouling our own nest with fossil fuel emissions and deforestation. Armed with insights from psychology and history, communicators of the climate change threat will more deeply understand the hostility to their message. Perhaps, communication will be more effective when shared concerns are acknowledged.

Incomplete climate science. It would be productive for advocates of prompt action also to concede that the message from climate science is not only unwelcome but also incomplete. Feedbacks from clouds, ice, and vegetation are only partially understood — thwarting precise prediction of future climate. The best and worst future climate outcomes consistent with today’s science are very different.

Pacala calls the worst credible climate outcomes “monsters behind the door.” Among the monsters are a five-meter rise in sea level by the end of this century, major alterations of the global hydrological cycle, major changes in forest cover, and major emissions of greenhouse gases from the tundra. The monsters open their door in a world of very strong positive feedbacks, a world that spirals out of control. Today’s science cannot predict how much atmospheric change would let these monsters in, nor how quickly they could enter.

Policymakers assessing the case for immediate forceful action and members of the general public deciding whether to endorse the policymaker’s decisions want to know the full story — both the average outcomes and the extremes (the “tails” of the distribution). In reaching a judgment about whether to act forcefully now, some will give greater weight to best guesses, others to the tails. The more risk-averse will assign greater weight to the tails.

Why, at the intersection of climate science and climate policy, is there more discussion of average outcomes than nasty ones? As I have speculated in a recent paper, one reason is that average outcomes are safer to talk about, because the science is more solid; there is less risk of being accused of alarmism. Also, acknowledging terrible outcomes of low probability requires acknowledging the other tail — a world with rising emissions but little change for quite a while. I often hear that any concession to benign outcomes (or, more accurately, outcomes that remain benign for a relatively long time) will foster complacency. I don’t understand that fear. In my experience, when I tell someone “we could be lucky,” and then I pause, the listener completes the sentence for me: “or we could be unlucky.” The listener does not hear a lullaby.

Arguments for action based on what we don’t know reinforce those based on what we do know. To build a case on what we don’t know, however, takes courage, because it requires revealing how much experts disagree. There are many contending views about sea-level rise, for example. Advocates resist calling attention to the coexistence of contending expert views — far more certain than I am that lay audiences translate such conflicts into justifications for procrastination. I think it should be possible to convey that Earth systems science is an evolving human enterprise where discordant views are the norm, and then to explain why certain issues have proved hard to resolve. My working assumption is that candor creates trust.

I wish some museum would prepare a climate exhibit with two adjacent displays that show two worlds with the same greenhouse gas concentrations at some future date (say, 50 years from now). One display would show a world in which human beings have been lucky and the worst manifestations of climate change have not yet arrived; in the other, we have been unlucky and at least a few of the more high-consequence outcomes are already on the scene. With the help of such an exhibit, the public would understand that neither those who proclaim with certainty that the world is facing imminent disaster nor those who seek to convince us that negligible suffering lies ahead can defend their case without going beyond today’s climate science.

Dangerous solutions. I was asked recently whether the right goal is to stop climate change as soon as possible. I realized that “as soon as possible” is not a simple concept. When driving a car, there are two ways to stop: slam on the brakes or brake carefully. Depending on the circumstances, either can be the right action.

Braking too slowly, in the context of climate change, creates excessive suffering from heat waves, floods and droughts, species extinctions, and sea level rise. Braking too quickly means implementing “solutions” in ways that create unnecessary distress. Many of the stabilization wedges promoted in Pacala’s and my 2004 paper are ready for vigorous implementation, including ending deforestation, pursuing energy efficiency in all economic sectors (while monitoring actual energy savings), expanding large-scale wind and solar power (while attending to the associated infrastructure), and ramping up carbon dioxide capture and storage projects at coal and natural gas power plants (while radically reducing emissions that affect public health). There is not much risk of braking too quickly in these cases.

For other stabilization wedges, fast implementation seems more fraught. When land is converted to biofuel plantations on a very large scale, the global food supply can be disrupted and bio-diverse ecosystems can be simplified beyond recognition. A global expansion of nuclear power without effective international constraints on uranium and plutonium can make nuclear war more likely (a risk further discussed in Alex Glaser’s and my 2009 Daedalus article). Preemptive programs to compensate for global warming by deliberately reducing incoming sunlight (not on the list of wedges back in 2004 but pressed today by a few analysts as a way to counter slow progress elsewhere) can bring on changes in climate as nasty as those the world is seeking to prevent. All such negative outcomes can be avoided, but only when the pace of implementation is moderated and strict conditions are imposed.

Because everybody wants to brake neither too slowly nor too quickly, those of us advocating prompt action on climate change would develop better rapport with our audiences if we were to concede that the lowest conceivable greenhouse gas emissions targets are not ideal. By definition, such targets throw caution to the wind.

Iterative risk management. In our Science paper, Pacala and I envisioned a world where “policies … would inevitably be renegotiated periodically to take into account results of R&D, experience with specific wedges, and revised estimates of the size of the Stabilization Triangle.” In effect, we were anticipating the concept of iterative risk management, which works forward from the present instead of backward from the distant future, and which features learning as we go. Iterative risk management focuses on targets 10 and 20 years ahead, in addition to targets 50 years ahead. Target updating might occur as often as every 10 years, to incorporate new insights from Earth-system science and lessons learned from wedge deployment.

Right now, especially in international politics, discussion focuses on a poorly defined, multi-century concept, the ultimate rise of the average temperature of the Earth’s surface. There are heated arguments about whether that rise should be capped at 1.5 or 2.0 degrees Celsius (2.7 or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), relative to its pre-industrial value. By contrast, if diplomats were debating the implementation of iterative risk assessment, negotiations would become more hard-headed. Specifically, there would be more attention to decade-scale global emissions targets.

What specific value for the 50-year target would I recommend? Given present knowledge, I would choose the target that is the analog of the one identified in the 2004 Figure in Pacala’s and my Science article, reproduced above. Today’s global emissions rate for carbon dioxide is 30 billion tons per year. For the world to emit in 2061 no more than 30 billion tons of carbon dioxide is as difficult a task as I could endorse today, taking into account the salience of other objectives to which I assign comparable importance, including preventing nuclear war, alleviating global poverty, and protecting the planet’s biodiversity.

To be sure, “present knowledge” will be modified every decade by new insights into our planet and ourselves, which is the reason for iteration. (For more on iterative risk management, see America’s Climate Choices, a report from the US National Academy of Sciences, published last May. I was a co-author of the report.) For iteration to be maximally productive, it must be accompanied by strong global research and development efforts targeted at both the climate problem and innovative responses.

I hope this short essay counters an unfortunate report two months ago in the blogosphere to the effect that I now regret Pacala’s and my wedges paper — that I consider it a “mistake” because it created false hopes that climate change could be achieved easily. The blog, in National Geographic News, came from a longtime environmental journalist, Doug Struck, who heard a talk I gave at Harvard University. (I responded the next day.) I must have expressed myself poorly. On the contrary, I believe the messages of the wedges paper are as important as ever. The global greenhouse-gas emissions rate in 2061 is a better focus of attention than targets a century or more in the future. Achieving an emissions rate in 2061 no higher than today’s is a goal that can be achieved by scaling up already deployed technologies. Given present knowledge, that goal is probably ambitious enough; pursuing tougher goals could lead us to opt for cures that are worse than the disease. And an iterative process for resetting goals is essential, in order to take into account both new science and newly revealed shortcomings of “solutions.”

To motivate prompt action today, seven years later, our wedges paper needs supplements: insights from psychology and history about how unwelcome news is received, probing reports about the limitations of current climate science, and sober assessments of unsafe braking.

Editor’s Note: This article is published in partnership with Climate Central. Public comments will be posted on its site.