The nuclear past is present

By Dawn Stover | January 6, 2015

A faded radiation warning sign near a nuclear crater.

A faded radiation warning sign near a nuclear crater.

President Obama signed legislation on December 19 to create the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, which will include portions of the Hanford Site in Washington state, Oak Ridge in Tennessee, and Los Alamos in New Mexico. Visitors to the park’s sites will be able to see more than 40 structures, including the Oak Ridge Y-12 complex (where uranium was enriched for the “Little Boy” atom bomb that devastated Hiroshima in 1945), the Hanford B reactor (the world’s first full-scale nuclear reactor, used to make plutonium for the “Fat Man” bomb dropped on Nagasaki), and historic buildings such as a high school and bank at Hanford that were used by Manhattan Project workers and their families.

Planning for the park dates back to 2001, when a panel of historic preservation experts called for the collective commemoration of the Manhattan Project’s “signature facilities.” After years of study and discussion, the National Park Service and the Energy Department in 2011 formally recommended the establishment of a three-site national park. Lawmakers finally approved it in late 2014 as part of a package of seven new parks and nine additions to existing parks—the largest expansion of the national park system since 1978. But while the Manhattan Project park has much to recommend it, the way in which it was created is characteristic of an extremely dysfunctional and regressive Congress that has slashed funding for parks, abused the defense budget authorization process, failed to meet its obligations to clean up nuclear waste, and allocated billions to breathe new life into the nuclear arms race of the Cold War.

A celebration of war? Then-Congressman Dennis Kucinich led opposition to the new park in 2012, saying that it would “celebrate the death of hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians.” (Kucinich lost his seat in an election later that year.) Supporters of the park counter that the National Park Service, which will provide interpretation for the public, will tell a story not just of science and engineering achievement but also of the Manhattan Project’s impacts on lives around the world.

There is no doubt that the Manhattan Project park could help transport people to an earlier time, proving invaluable for public education about America’s role in World War II and the Cold War. Seeing it makes it real. The Atomic Heritage Foundation, which lobbied for the park, points out that it will include the building where Canadian scientist Louis Slotin received a fatal dose of radiation during an accident in 1946. It’s worth noting, though, that all three of the park sites will be located in communities that have historically been supportive of—and, more important, supported by—the development of nuclear weapons.

Whose history is it anyway? It is telling that the park was finally approved only because it was attached to the must-pass 1,648-page National Defense Authorization Act for 2015. (When it was proposed earlier as stand-alone bipartisan legislation, the park failed.) The defense authorization act included no fewer than 70 public lands projects, many of which have absolutely nothing to do with defense.

Although conservationists claimed the package as a victory, it included a particularly bitter pill that had previously been rejected in the House of Representatives: a land swap that enables Resolution Copper—majority-owned by foreign mining giant Rio Tinto—to proceed with developing a mine on Native American ancestral lands in New Mexico, primarily of the Apache tribe. The defense bill also transfers more than 1,600 acres—part of the homelands of the Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla tribes—to the Community Reuse Organization of the Hanford Site for industrial development. Preserving a history that dates back thousands of years is apparently of less value to the United States than preserving the mid-20th century apparatus of war.

The value of history. The $585 billion defense bill provides no funding for any of the newly created park units. The land and structures that will be part of the Manhattan Project park already belong to the federal government and are simply being transferred to new management. It might even be cheaper to operate them as a museum rather than demolish them. Still, the lack of funding for the new park units underscores legislators’ priorities.

Although the National Park Service received a $55 million budget increase for 2015 (an increase of about 2 percent, about the same as the rate of inflation), it has suffered from a lack of funding in recent years. As the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA) notes, Congress cut the agency’s budget by nearly 8 percent between 2010 and 2014, and annual operations shortfalls have forced park superintendents to close facilities, lay off park rangers, and limit educational programs.

If Congress really cared about parks and education, it would put more money towards those things instead of the massive expenditures just approved for military activities. According to the NPCA, a median-income American household pays less than $3 in taxes each year for all of our national parks combined. Surely we can afford more.

The wrong priorities. The federal government is also underfunding the cleanup of Hanford and other defense sites contaminated by nuclear waste generated during weapons production. Cleanup has been Hanford’s main mission since the late 1980s, with more than $40 billion spent so far, but the 30-year cleanup plan is way behind schedule, and completion is not expected for 70 years or more. The Department of Energy has already announced that it won’t meet the agreed-upon deadline for emptying leaking waste tanks at the site.

“I don’t want Hanford remembered just as a cleanup site,” said Sen. Patty Murray of Washington, a supporter of the new park who has also made it one of her top priorities to fight for cleanup money. In both cases, a lack of sufficient funding causes delays that increase risk, making it that much more difficult to protect the land, water, and buildings at Hanford and other nuclear sites.

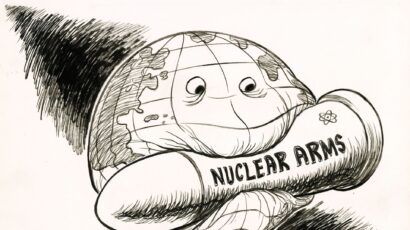

Mired in the past. The creation of the Manhattan Project park reflects the last Congress’ warped values, which unfortunately are not likely to change under the new one. The most worrisome thing about the park is not that it celebrates the development of nuclear weapons, but rather that it suggests such activity is a thing of the past.

Just look at the description of the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota: Describing “what is so special about this place,” the National Park Service writes in the past tense: “Nuclear war loomed as an apocalyptic shadow that could possibly have brought human history to an end.” Can the National Park Service be ignorant of the fact that missiles remain on station, nuclear weapons are still being stockpiled, and saber rattling did not end with the fall of the Berlin Wall?

The same Congress and president that approved the creation of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park also approved huge new expenditures to refurbish nuclear weapons and keep the nation’s weapons laboratories at full operation. As the Bulletin noted last year, “post-Cold War reductions of nuclear weapons have slowed” and “the nuclear nations have undertaken ambitious nuclear weapon modernization programs that threaten to prolong the nuclear era indefinitely.” The Obama administration approved an upgrade to the B61 nuclear bomb that will effectively create a guided standoff weapon. Its price tag is expected to top $10 billion, with each bomb costing more than if it were made from solid gold.

These are signs of a government utterly lacking in leadership and foresight when it comes to nuclear weapons. Instead of enjoying junkets to exotic destinations such as Rome and Tanzania, our federal representatives should take a group field trip to the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. If they can remember the past, maybe they won’t be condemned to repeat it.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Columnists, Nuclear Weapons, Special Topics