Arms control 2.0? With open source tools, desktop sleuths can go where governments won’t

By Henrietta Wilson, Olamide Samuel, Dan Plesch | July 27, 2020

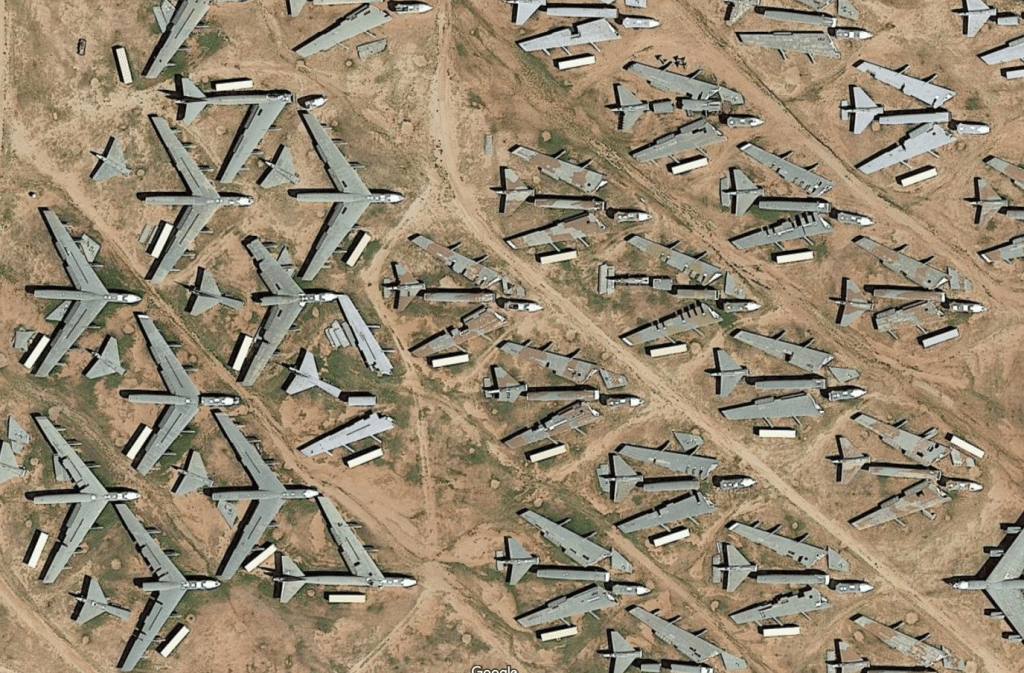

In the 1990s, to comply with the START treaty, the United States arrayed 365 B-52 bombers in the Arizona desert, cut them into pieces, and left them there for months so that Russia could verify their destruction via satellite imagery. Photo credit: Google Maps and Maxar Technologies.

In the 1990s, to comply with the START treaty, the United States arrayed 365 B-52 bombers in the Arizona desert, cut them into pieces, and left them there for months so that Russia could verify their destruction via satellite imagery. Photo credit: Google Maps and Maxar Technologies.

The arms control community was outraged by the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the Open Skies Treaty in May 2020. The treaty enhances transparency and builds confidence between the state parties, allowing them to conduct specified numbers of unarmed flights over each other’s territories, under regulated conditions. The US decision to unilaterally leave this regime marks the latest in a set of international actions that undermine the complex mix of international treaties designed to engender global stability. But while geopolitical tensions mean that there is unlikely to be a quick breakthrough to reverse this trend, other means may support the transparency and confidence-building functions of internationally negotiated verification arrangements.

The potential for monitoring and verification has been transformed by new information technologies. The internet’s capacity to generate and publish data, as well as make available tools for visualizing and analyzing it, means that activities and artifacts are discernible in a way never before possible. There are now numerous free-to-use tools for remotely tracking planes and ships, as well as ready access to commercial satellites and global systems for monitoring natural disasters. Global environmental remote sensing holds promise from an arms control perspective, since environmental monitoring lends itself to detection of emissions associated with weapons production and use. New technologies have also expanded the possibilities of previous investigative research tools, for example by increasing access to global news and improving global communications and networking.

Nongovernmental organizations are already using these and other means to identify and monitor weapons flows and related threats. Such efforts include the Vienna-based Open Nuclear Network’s work to “identify, track, understand, and address emerging threats”; the London-based Royal United Services Institute’s Project Sandstone, which works to reveal illicit North Korean shipping networks; and a proposed multi-agency Somali project enabling citizens to explore allegations of illegal radioactive waste dumping in Somalia and uncover illegal uranium smuggling in the country, via the development of a mobile phone application. Similarly, citizen journalists at Bellingcat have pioneered novel techniques for open source investigations revealing numerous illicit activities and are part of a wider set of organizations that have re-energized investigative journalism.

These initiatives have overtaken earlier understandings of what has been considered possible in terms of international monitoring and verification. Previously, verification options were tied to what was politically achievable—verification arrangements could only include provisions agreed by states. To reach agreement, negotiators from all sides had to balance transparency needs against the necessity of protecting sensitive commercial or military information. But the widespread accessibility of technological tools today means that transparency tasks are not limited to systems that can be agreed by governments within international negotiations.

Open source verification—nongovernmental monitoring of activities through publicly-available information—empowers transparency and accountability and has been linked to the achievement of discrete political goals. For example, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project and the investigative website Disclose have provided evidence that French tanks were central to the battle to control Hodeida, Yemen, in 2018, refuting the French Defense Minister’s earlier claim that land-based equipment sold to Saudi Arabia was used only for defensive purposes at the border. Similarly, Forensic Architecture, an organization based at Goldsmiths, University of London, has built 3-D models of bomb craters to understand the details of chemical weapons use in Syria, allowing the international community to counter disinformation about the attacks and generating better knowledge about likely perpetrators.

International arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament treaties demonstrate that the international community can devise innovative systems for managing the political complexities involved in international monitoring and verification. They also provide the means for the international community to generate transparency and build confidence between states, and demonstrate the benefits of doing so. For example, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe has developed and implemented effective confidence- and security-building measures; the Chemical Weapons Convention has established systems for inspections that would build assurances without compromising sensitive commercial or defense information. UNSCOM and UNMOVIC, two UN Security Council–mandated special commissions that implemented inspection regimes in Iraq, demonstrated that the verified elimination of weapons of mass destruction is technically possible.

However, there is a recognized need for new approaches to regulating weapons systems. Existing arms control and disarmament achievements are at risk in several dimensions. Hard-earned, carefully negotiated agreements are being unraveled, with the Trump administration unilaterally withdrawing from the US-Russia Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreement with Iran, and the Open Skies Treaty. Meanwhile, many other treaties are seen as vulnerable, either because of a perceived inability to meet states parties’ expectations, or because they are confined by the limits set in their negotiated and legally-binding texts. For example, the terms of the Chemical Weapons Convention have impeded the task of understanding and attributing use of chemical weapons in Syria; the New START treaty will expire automatically in February 2021 if the United States and Russia do not choose to extend it; the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty members have not delivered enough progress on their Article VI disarmament commitments; and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons seems functionally confused, given that no nuclear weapons states are likely to support it in the near future.

In a world in which geopolitical realities are limiting the ability of the international community to reinforce—let alone extend—cooperative, treaty-based solutions to regulating armament and disarmament, open source verification can complement the transparency functions that were previously the remit of international treaties.

While it can’t replace or exactly reproduce the scope of internationally negotiated verification regimes, open source investigative work can in some instances go beyond such regimes. Open source verification projects tend to be smaller, can be more flexible in meeting monitoring challenges, and may allow the international community to bypass the constraints of traditional verification. In some cases, open source analysts’ local knowledge gives them access to more detailed social and geographical information than is possible for bigger organizations. On top of this, many open source verification projects are transparent in their methodologies, data, and findings, meaning that their work is reproducible and open to scrutiny, and that they have in-built processes for authenticating their work.

Existing open source verification shows that technologies for nongovernmental monitoring not only exist—they are pervasive, with numerous technologies already tracking illicit activities, global transport networks, and systems for disaster tracking. There is now an opportunity to recognize these activities as part of a larger global weapons tracking service and consider how they can complement and support the work of high-diplomacy interstate efforts. In an age of Google Earth, it no longer feels like sci-fi speculation to envision a world in which governments and citizens can track the movement and use of weapons anywhere in the world virtually in real time.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Open skies treaty, arms control, open-source intelligence, open-source monitoring, treaty verification

Topics: Nuclear Risk