Why we need to take back Earth Day

By Adam Sobel | April 21, 2021

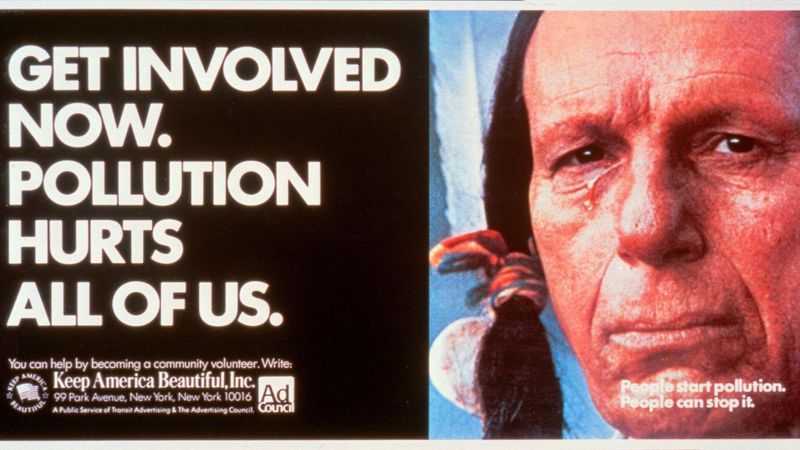

A Keep America Beautiful advertisement by the Ad Council, as it appeared in 1971. Image courtesy of the Ad Council, Original Credit: HANDOUT

A Keep America Beautiful advertisement by the Ad Council, as it appeared in 1971. Image courtesy of the Ad Council, Original Credit: HANDOUT

I consider myself an environmentalist, and I am a climate scientist by profession. You might think Earth Day would hold some significance for me.

It does not.

But I’m also a cranky person, prone to Grinch-like views on such things. So I did a quick, unscientific poll of a small sample of several friends and colleagues who work in different aspects of climate and environment in order to see if my feelings are unrepresentative.

They are not.

Some respondents expressed that they think Earth Day may be good for raising consciousness among others, but none claimed to have evidence of this, and no one expressed that the day holds much meaning for them personally. Based on my experience of Earth Day over my many years of adult life, I will extrapolate beyond my little poll and speculate that a sizeable fraction of the people you might think would get excited about Earth Day do not.

Why not? Is something wrong with the day, or with us?

The prompt for this thought process came from an article by Emily Atkin and Judd Legum about an Earth Day event being put on by the American Petroleum Institute (API) featuring many prominent and respected climate advocates as speakers. The article mulled over the question of whether these people should have declined their invitations to participate. The event is clearly an attempt at greenwashing, on the part of an organization that represents the fossil fuel industry at its climate-denying, carbon-pushing worst.

I’m more interested here, though, in whether the API episode, or any other like it, says anything about Earth Day itself. Is its value to greenwashers the reason why neither my friends nor I care much for the holiday?

I don’t think that’s quite it. No holiday is safe from being co-opted. Bad actors can hold events intended to camouflage their badness on Christmas, or Veterans Day, or Martin Luther King Day, and we don’t blame the day itself.

A more substantive reason might be that we should care about the Earth every day, not just on one tokenizing day (or week, as it seems to have become). This was expressed by one respondent to my poll, someone who organizes volunteer events year-round for a local government agency with an environmental agenda in a major US city. This person—who asked not to be named for obvious reasons—feels that Earth Day actually detracts from their organization’s overall mission by funneling the public’s interest into a single day.

Fair enough. But this, too, can be said about nearly any calendar date that’s associated with a cause. We should learn Black history even when it’s not February, and support workers’ rights even when it’s not the first Monday in September, but that doesn’t invalidate those occasions.

No, I think the roots of my distaste are deeper. Earth Day carries a cultural framing that no longer fits the social movement associated with it.

The first Earth Day, in 1970, grew out of the environmental movement’s surge to prominence in the 1960s. The official history of the holiday credits it with helping to establish the US Environmental Protection Agency, the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, and other environmental laws and governmental structures. These are important successes, and they shouldn’t be forgotten or minimized.

But in some respects, that historical moment was the high-water mark of the environmental movement as it was constituted then. My colleague Michael Gerrard, who leads the Columbia Center for Climate Change Law, points out that there have been no major environmental laws passed in the United States in the last 30 years. International climate negotiations, at least until the Paris agreement in 2015 (and the jury’s still out on that), have been a complete failure, in large part due to US intransigence, which in turn is a consequence of the influence of the companies that the API represents.

The environmental movement that grew out of the 1960s carried the utopianism of that era, but it was being greenwashed almost from the beginning. The famous 1971 public service advertisement showing a native American (who really wasn’t one) crying about pollution was sponsored by companies that manufactured soft drink containers to shift blame for pollution from them to consumers, a tactic now familiar in the climate context as well. The ad was nonetheless effective; it helped to inspire lifelong, activist environmentalism in some who saw it as children (I married one such). But that movement eventually became marginalized and ineffective in national politics, under continued assault from the anti-government market fundamentalism that began with Reagan, was made more militant by Gingrich, and ultimately led to Trump.

At the same time—perhaps in response to Trumpism as much as to the climate crisis—the movement for climate justice has suddenly gained new traction in the last few years. Powered by young activists, it has now got climate to the top of the Biden administration’s agenda, a situation no one could have anticipated a few years ago. But this newly powerful movement represents a substantial change from the one that created Earth Day.

Today’s climate movement explicitly recognizes, in a way that the whiter, older, and more upper-middle class environmental movement of 1970 did not, that climate is a social justice issue. It recognizes that the harms resulting from unfettered burning of fossil fuels are disproportionately felt by those already at greatest disadvantage (including nonhuman species and future human generations, as well as those marginalized along racial and economic lines today), while the benefits go to the most privileged, and that some very powerful coalitions are fighting to prevent any remedy, even as they may be sponsoring Earth Day events.

In doing so, today’s climate movement connects climate to other social justice issues and forces us to accept that solving the problem requires us to engage in a broad political conflict. It won’t be solved by asking everyone to reduce their own personal carbon footprint. Nor will it be solved by just getting scientists or other spokespeople to explain the problem in the right way, given the well-funded and effective disinformation campaign that emerged in the decades following the first Earth Day, and that has now metastasized into an entire right-wing media ecosystem full of “alternative facts.”

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t want to cancel Earth Day, exactly. But we need it to recognize what we are up against.

Martin Luther King Day keeps its meaning because no one can explain who Dr. King was without talking about the social movement he led and the challenges it faced—the way he died, by itself, makes that impossible to ignore. Earth Day needs to lose its anodyne character and become more like that. Maybe changing the name would do it—how about “Climate Justice Day”?

But even if we keep calling it Earth Day, we could change the culture around it so it’s clear to anyone that this social movement is not about celebrating how good it feels to recycle or watch nature documentaries. It’s a struggle, against powerful opposition, to mitigate the cascading catastrophes that are being inflicted, for the benefit of the few, upon human and nonhuman alike.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

CLIMATE JUSTICE DAY, thank you, sounds more accurate, “Climate Justice Day”, thanks…..let’s get it changed ASAP!