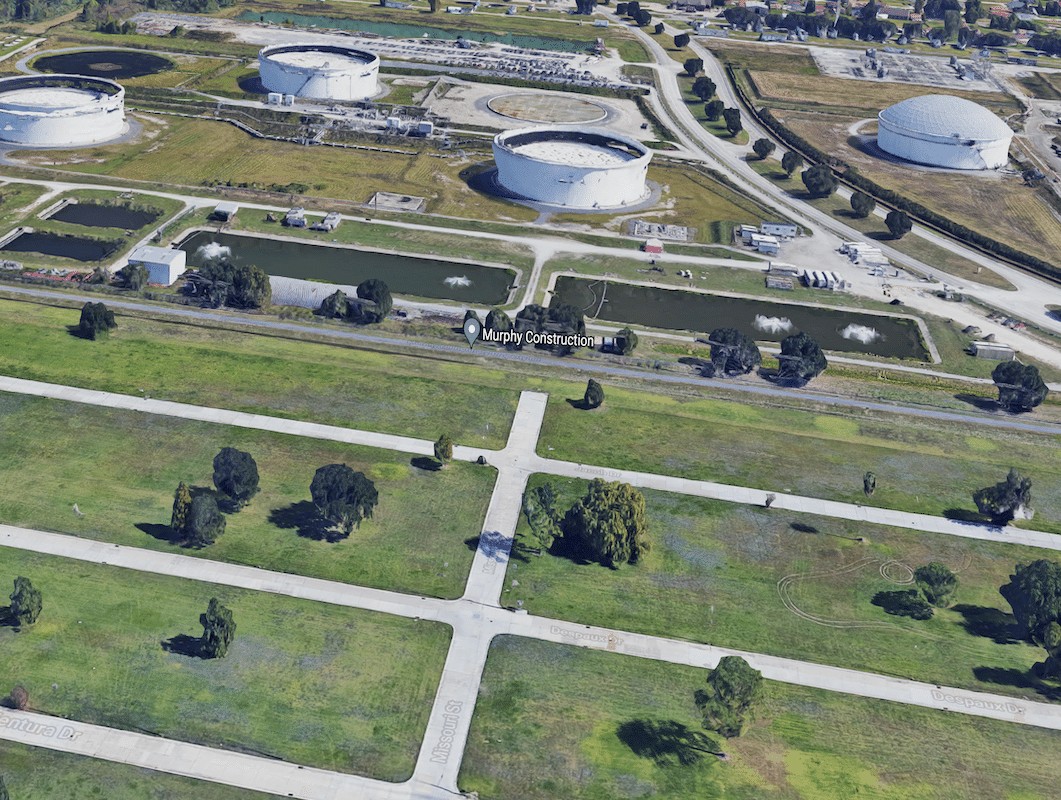

The Houston Ship Channel winds through the city's colossal industrial landscape of tanks filled with chemicals. (Glasshouse Images)

Jim Blackburn likes to drive out-of-town visitors across the high arch of the Fred Hartman Bridge for the best view of the Houston Ship Channel, a 52-mile-long waterway crowded with the continent’s largest collection of petrochemical plants and oil refineries. Sprawling over what had been low coastal marshland is a jumble of pipelines, smokestacks, storage tanks and cargo ships. For the full impact, the environmental lawyer sometimes brings guests after sunset.

“You come over this bridge at night, and you see all the lights and steam and the flares going off all over the place,” he said as his car crested the span. “One time, I had an Episcopal priest from Seattle with me. She looks down at all this and says, ‘This is what hell looks like.’”

Blackburn let out a sour chuckle. The ship channel’s transformation into a true hellscape, he said, is yet to come. “Throw a real hurricane at this and it’ll be the largest environmental disaster in US history,” he said.

Blackburn, who teaches at Rice University, has been prophesying this calamity for more than a decade. What might have seemed a grim fantasy a few years ago looks increasingly likely with each storm that rakes across the industrial corridors of Texas and Louisiana.

His end-times vision begins with a mild-mannered tropical storm taking shape somewhere in the mid-Atlantic. As it gathers strength in the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, the storm builds into a hurricane hundreds of miles wide with winds topping 130 mph. Instead of striking just east of Houston, as Hurricane Ike did in 2008, or veering over to Louisiana, as Laura did last year, this storm plows straight into the heart of Galveston Bay, pushing it into a nearly 30-foot-high bulge and dropping it on the bay’s heavily developed west side, an area that’s home to more than 800,000 people.

Thousands may die from the initial burst of wind and water, but the real terror begins when the storm surge squeezes into the Houston Ship Channel. The surge, he said, will break ships off their moorings, cleave oil pipelines, and pummel thousands of storage tanks holding the raw material for everything from paint thinners to jet fuel. This toxic stew of oil, chemicals, and debris will flood urban bayous, spill into neighborhoods, and eventually wash back into the bay.

“This is what hell looks like.”

Blackburn’s bleak prediction, developed with computer modeling by Rice’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disaster (SSPEED) Center, loses doubters with each passing storm.

“The storms and types of weather we’re having are more extreme,” said MaryJane Mudd, executive director of East Harris County Manufacturers Association, an alliance of chemical producers along the ship channel. “We are having to prepare for things we’ve never considered before.”

Despite the risks, the industry has been slow to adapt. Companies are not building bigger floodwalls, altering facility designs, or shifting development inland. Federal and state governments are doing little to push industries. Regulations remain frozen as the climate warms, increasing the likelihood of stronger and more frequent storms.

Industry leaders and regulators are instead banking on a nearly $30 billion storm protection project known as the Ike Dike. Named for the hurricane, the vast system of walls, gates, and levees would make Galveston Bay a veritable fortress that could be sealed up when hurricanes threaten.

It’s ambitious and expensive, but Blackburn says it will be too little, too late. Likely to take the better part of two decades to build, the Ike Dike won’t hold up to the worst hurricanes. “Look, it needs to be built,” he said. “But it needs to be built for the bigger storms to come. It will be way outdated once it’s constructed.”

Coast Guard aircrews assessed flooding from Hurricane Harvey along the Houston Ship Channel, August 31, 2017. (US Coast Guard / Petty Officer 1st Class Patrick Kelley)

Measuring Risk

The risks hurricanes pose to industrial areas aren’t limited to Houston. More than 4,876 sites that handle toxic chemicals sit in storm- and flood-prone areas of Texas and Louisiana, a Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and Massachusetts Institute of Technology analysis of flood plain and industrial data shows.

Home to the bulk of the country’s petrochemical infrastructure, the two states are under growing risk from rising seas, hurricanes, river flooding, intense rainfall, and other threats posed by climate change. Of those sites in Texas and Louisiana, 1,987 were in locations with moderate risk and 2,889 were at high risk.

The Houston area has about 900 facilities with toxic chemicals in areas at risk to floods from storms. New Orleans has more than 150. “We know the risk is high in the ship channel and around Houston, but our analysis emphasizes that this is a risk that's prevalent in a lot of places,” said Adam Schlosser, an MIT climate risk researcher who led the analysis. “Hopefully, this will raise eyebrows and call attention to how severe these issues are.”

The Bulletin-MIT analysis looked at sites listed in the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxics Release Inventory, a database in which facilities self-report hazardous chemical releases in the air, in water, or on land. Most of the more than 21,000 such facilities across the country are involved in large-scale chemical production, manufacturing, mining, and waste treatment.

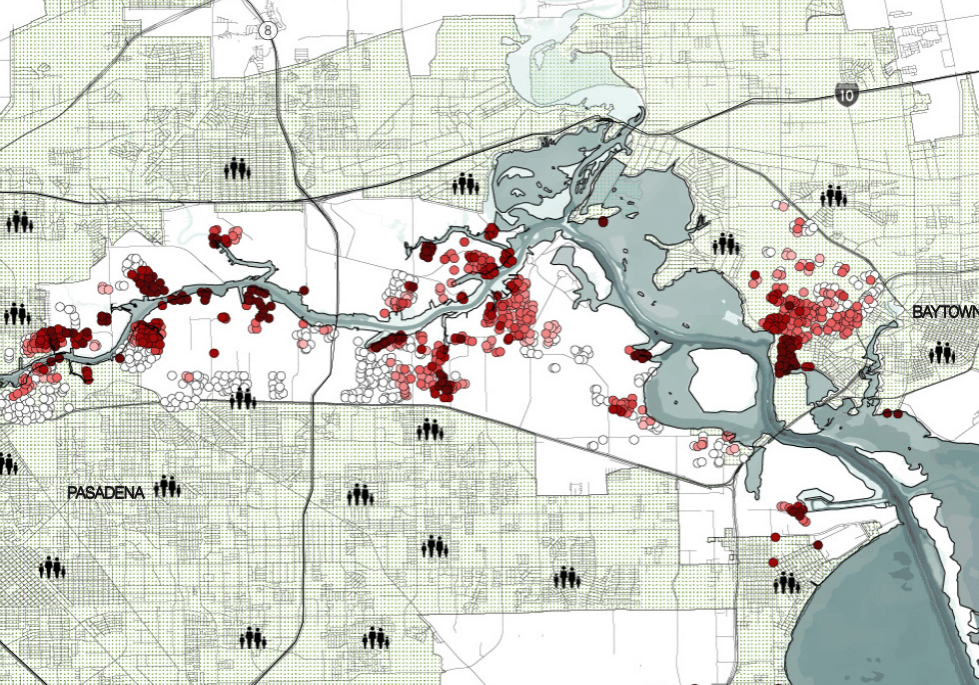

Interactive: Flood risk and toxic chemicals on the Gulf Coast

ABOUT THE MAP

There are nearly 5,000 facilities in Texas and Louisiana that have handled toxic chemicals in recent years and are located in areas prone to storms and flooding. This map displays them, one to a “dot”; clicking on a dot provides details, including the chemicals reported by each facility and the average flood risk around each site.

By zooming in and clicking, you can see chemicals reported to the EPA, average flood risk, street address, and parent company name. You can also see which sites are near a specific address via the search bar at the top right of the map.

The shaded areas identify the calculated average flood risk (or flood factor) for each ZIP code where a facility is located. The legend to the right side of the map reflects the color-coded risk score scale, from minor to extreme risk.

DATA SOURCES

Sites: All sites on this map were identified through the EPA’s Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI) model, which in turn draws on the agency’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), a database of toxic chemicals that “may pose a threat to human health and the environment.”

The TRI inventory currently identifies 770 toxic substances (including, for instance, cyanide, ammonia, hydrochloric acid, and lead) that must be reported annually by facilities that manufacture, process, or otherwise use them. This map represents the full history of related chemical activity as reported to the EPA by government and industrial facilities in Texas and Louisiana since 1988, through 2018.

Flood factor: The average flood risk score, represented by the shaded areas and in the details for each site, is drawn from the First Street Foundation’s Flood Model, a “nationwide probabilistic flood model that shows the risk of flooding at any location in the contiguous 48 states due to rainfall (pluvial), riverine flooding (fluvial), and coastal surge flooding.” The flood risk scores presented here are averaged for facilities within a single ZIP code.

An overview and complete explanation of the methodology behind the average flood risk score is available on the First Street Foundation website.

Interactive: Flood risk and toxic chemicals on the Gulf Coast

About the map

Data sources

There are nearly 5,000 facilities in Texas and Louisiana that have handled toxic chemicals in recent years and are located in areas prone to storms and flooding. This map displays them, one to a “dot”; clicking on a dot provides details, including the chemicals reported by each facility and the average flood risk around each site.

By zooming in and clicking, you can see chemicals reported to the EPA, average flood risk, street address, and parent company name. You can also see which sites are near a specific address via the search bar at the top right of the map.

The shaded areas identify the calculated average flood risk (or flood factor) for each ZIP code where a facility is located. The legend to the right side of the map reflects the color-coded risk score scale, from minor to extreme risk.

To determine storm and flood risk, the analysis used data from the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit flood and climate change research firm. First Street’s risk calculations draw from a larger and more up-to-date pool of data than federal flood maps.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has produced maps covering only a third of the nation’s streams and just under half of shorelines, according to a 2020 report by the Association of State Floodplain Managers. That means vast areas of the country are “less able to be resilient because the foundational flood data does not exist,” the report says.

FEMA also doesn’t account for flooding caused by intense rainfall, a growing problem as the climate changes. Storms are dumping more water than many urban drainage systems, including ones in New Orleans and Houston, were designed to handle.

“FEMA maps don’t look right when you compare them to where it actually floods in Houston,” said Bill Read, a former director of the National Hurricane Center who lives just south of the city. “They don’t match how the real world works.”

The standard methods of calculating hurricane strength and probability are also failing to keep up with changing climate. A so-called “100-year” storm, which has a one percent chance of happening in any given year, may now occur every few years, and monster “500-year” storms are popping up every 50 to 100 years. “All of these sites (in the Bulletin-MIT analysis) might have been considered safe in the past, but they may not be safe in the future,” Blackburn said. “We need to prepare for what’s to come.”

Residue from oil spills tainted floodwaters in Meraux and Chalmette, LA after Hurricane Katrina. (Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality)

Worst Case Scenario

Scientists have created several storm models that reanimate Hurricane Ike and put Houston back in its crosshairs. The real Ike was aiming for the city as a Category 4 storm but dropped to a Cat 2 just before swerving north to a less populated stretch of Galveston Bay. Ike was still plenty bad, killing 77 people in Texas and causing more than $27 billion in damage. But had it stayed on course for Houston, as a future storm may do, the outcome would have been much worse, said Hanadi Rifai, a hurricane resilience researcher at the University of Houston.

“There would be catastrophic damage,” she said. “It would produce a surge about 25 feet high and send it into the ship channel, where almost every facility would be affected.”

The narrow channel would concentrate the surge, intensifying its power much like a thumb pressed over the opening of a garden hose. In its path: about 900 industrial facilities and more than 4,300 above ground storage tanks.

“It really is a potential Chernobyl,” said John Pardue, a hazardous substances researcher at Louisiana State University. “The Houston area has such a large number of tanks and the potential for so many chemical releases all at once.”

Michel Bechtel, the mayor of Morgan’s Point, a small town at the mouth of the ship channel, knows first-hand the risks storage tanks pose. When Katrina flooded Chalmette, La., Bechtel’s hometown, it ruptured an immense tank at a Murphy Oil refinery, releasing more than a million gallons of thick black crude. The oil and floodwater inundated nearly 2,000 homes, including Bechtel’s parents’ house and a cottage Bechtel, then a newlywed oil engineer, had just built to start his family.

“It was just a total wipeout for everybody,” he said. Morgan’s Point sits across the channel from a dense cluster of tanks. “There's lots of stuff in those tanks that you don't want floating around or washing back into the bay.”

The tanks contain flammable and toxic materials used to make a variety of products, including plastic, solvents and gasoline.

The Murphy Oil spill was one of dozens of releases from storage tanks during Katrina and Hurricane Rita, a storm that struck Louisiana a few weeks later. All told, more than seven million gallons of oil and other hazardous substances were found to have seeped from tanks after the two storms. During Hurricane Harvey, about 530,000 gallons of petrochemicals spilled from damaged tanks in the Houston area.

Tanks have suffered damage and released hazardous chemicals during almost every major hurricane to strike the United States since 1990, according to researchers at Rice University.

Storms can damage storage tanks in a variety of ways. Pressure from wind or floodwaters can buckle and break tanks. Many tanks, including the one near Bechtel’s home in Chalmette, can be picked up by floodwaters and then dropped when the flooding subsides, cracking their lightweight walls like an egg.

Harvey highlighted the vulnerability of what are known as “floating roof” storage tanks. Designed to float up and down depending on a tank’s liquid levels, the roofs didn’t hold up well to heavy rain. At least 15 floating roofs sank or tilted during the storm, releasing almost 400 tons of cancer-causing benzene and other toxic vapors into the air.

One million gallons of crude oil spilled into the flooded residential streets of Chalmette, LA, when surging water from Hurricane Katrina displaced a storage tank by more than 30 feet. (EPA / Google)

“It was just a total wipeout for everybody. ... There’s lots of stuff in those tanks that you don't want floating around.”

Chemical reactions are another serious threat. Two of the largest chemical fires along the Gulf Coast in recent years were caused by storm-triggered reactions. During Harvey, the Arkema organic peroxide plant in Crosby, Texas suffered flooding that knocked out the facility’s backup generators. Chemicals requiring refrigeration heated up and ignited, producing a plume of toxic gas that forced the evacuation of about 300 homes and sickened several emergency responders, some of whom collapsed in fits of coughing and choking.

In 2020, Hurricane Laura’s winds ripped open part of the sprawling BioLab Inc. complex near Lake Charles, La. and allowed rain to seep in, sparking a reaction with the vast stores of chlorine. The chemical combusted, producing the same greenish yellow gas that was used as a weapon during World War I. The fire and toxic plume prompted a shelter-in-place advisory for the surrounding area. Residents living within a one-mile radius of the facility were urged to shut their doors and windows and turn off air conditioners. Fortunately, much of Lake Charles had evacuated prior to the storm, and no serious injuries were reported.

“Harvey and Laura showed us we’re still vulnerable and not prepared,” said Casey Kalman, a climate hazards researcher with the Union of Concerned Scientists. “These are lessons we’re still learning, and we do it over and over.”

Blackburn said there are indirect threats to chemical facilities, including storm debris, that should be getting more attention. Especially concerning are the seemingly innocuous shipping containers stacked by the thousands along the channel.

“I'm not at all worried about what's in them,” he said, noting the containers are more likely to be loaded with bananas or bicycles than anything toxic. “But these things, and anything else the storm knocks down into the water, becomes a battering ram.”

Storm surge and flood waters can bash the containers into storage tanks and chemical facilities, increasing the likelihood of harmful releases.

Alongside Morgan’s Point is a Port of Houston facility stacked with containers seven stories high. “There’s such an immense amount of them,” Blackburn said while driving alongside gridlocked semi-trucks waiting to be loaded with the containers’ goods. “If you unleash any of these containers, they're going to go straight into these facilities, and then over into the residential area back to the south.”

A shrimp boat sits on a fuel dock in Port Arthur, TX, following Hurricane Rita in 2005. (Doug Helton, NOAA/NOS/ORR)

Houston Impacts

Blackburn kept an eye on an altimeter as he drove inland from Morgan’s Point. Well into the maze of new housing developments spreading south of Houston, he stopped to note the height: a high and dry 17 feet above sea level. “All of it, under water,” he said. “When we get that 25-foot surge, it ain’t stopping here. This’ll be under eight feet of water, and it’s not even considered part of a floodplain.”

The surge will likely plow through the industrial areas, “picking up God knows what,” before spilling it into La Porte, Clear Lake City, parts of Pasadena and other areas between Houston and the bay. Houston, while more than 20 miles from the coast, likely won’t be spared. Buffalo Bayou and other urban waterways are linked to the ship channel and will serve as conduits for the contaminated floodwaters to penetrate downtown Houston, Blackburn said.

Many people might evacuate before the storm, making the full risk to human lives hard to predict. But the harm to the bay isn’t. Rice University scientists believe a 24-foot surge would break open enough storage tanks to release 90 million gallons of oil and other hazardous substances into the bay.

“It will destroy Galveston Bay as a functioning estuary,” Blackburn said.

Houston-area Flood risk and toxic chemical sites

Houston-area Flood risk and toxic chemical sites

The bay is one of the most productive estuaries in the United States, likely trailing only Chesapeake Bay, which is seven times its size. About 60 percent of the shrimp caught off the Texas coast comes from the bay, as well as half the oysters and about a third of the blue crab. The bay is also home to dolphins, pelicans, threatened shorebird species, and endangered sea turtles.

The economic impacts of a hurricane striking the ship channel would reverberate across the country.

The refineries along the channel produce about a quarter of the nation’s gasoline and 60 percent of its jet fuel. The US military depends on ship channel producers for about 80 percent of the fuel for its fighter jets and other aircraft. Gas prices would explode if ship channel production was forced to cease, said Bob Mitchell, president of the Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership.

“Oh, my God, the impact that’d have,” he said. The cyberattack in May that forced the shutdown of the Colonial Pipeline sent gas prices over $3 per gallon. “But if we get hit with a big storm, gas will be $10 to $12 a gallon,” Mitchell said. “I guarantee it.”

This time-lapse video of a ship navigating the Houston Ship Channel toward the Gulf of Mexico demonstrates the enormity of the industrial zone. (Louis Vest via Flickr; CC-BY-NC)

The Houston area is also a major producer of the plastics and other raw materials that go into a range of manufactured goods. “We produce the (material) for everything from capsules for pills to the tires for cars,” Mitchell said. Slowing down these varied outputs would be felt in a wide range of sectors, from health care to retail and restaurants.

Cleaning up pollution and debris in the channel after a major storm could take weeks or months, industry leaders say. A University of Houston analysis estimated closing the channel for just a few days would amount to $1 billion in losses from shipping delays and expired or lost goods.

“When there’s a breakdown in our logistics pyramid, I’m sorry—you’re screwed,” Mitchell said. “It affects the whole USA and the globe.”

“Essentially, the response is to evacuate.”

A vehicle drives past oil storage tanks through floodwaters from Hurricane Harvey in Texas City, August 29, 2017. (Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Ignoring Threats

These are problems “that are just begging for regulations,” Pardue said. Yet, states and the federal government have offered only a thin patchwork of rules and suggestions, and most of them fail to address climate risks directly.

“Most of the regulations we have are for dry weather spills,” Pardue said. “They require little earthen berms around chemical storage tanks in case something goes wrong.” Many of these “secondary containment” barriers are designed to hold a spill—from a broken valve or pipe, for example—rather than prevent floodwaters from reaching storage tanks. The 8-foot-high berm around the Murphy Oil tank did little against Katrina’s floodwaters, and similar protections will likely do even less against the 25-foot surge predicted for the ship channel.

The federal government leaves tank design standards and spill prevention guidelines to the American Petroleum Institute, but these lack the teeth of regulations. And much of the API’s guidance in hurricane-prone areas focuses on wind, not rainfall or flooding.

Industry standards for floating tanks, for instance, recommend rain drainage capacity of 10 inches over a 24-hour period. But more than four times that amount fell during Harvey. To prepare for storms, industrial plants often burn off chemicals or fill tanks to make them heavier and less likely to float away. “But that’s the extent of it,” Rifai said. “Essentially, the response is to evacuate except for leaving essential personnel to deal with whatever it is they’re making.”

By contrast, federal regulators take the risk of extreme surge seriously for nuclear plants. After the Fukushima disaster in 2011, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission recommended that even low-risk surges be incorporated into the design and permitting of nuclear power plants.

“Fukushima changed their view of what was likely to happen because Fukushima was unlikely to happen,” Blackburn said. “It seems like it takes events like that. I think it's gonna take a hurricane destroying a whole bunch of chemical tanks to cause the type of reevaluation of these issues. And it's unfortunate, but that's just the way this seems to work.”

Efforts to strengthen chemical disaster rules have ebbed and flowed depending on who occupies the White House. In 2013, President Barack Obama signed an executive order requiring better chemical storage, wider disclosure of locations with hazardous chemicals, and third-party accident investigations. The Trump administration reversed the rules, siding with industry groups that argued the costs of adhering to the stricter requirements would far outweigh the benefits. The rules could swing back if the Biden administration makes good on its pledge to overhaul several chemical industry regulations.

Many companies express confidence in their facilities publicly. Privately, they know they’re in danger.

The industry is already doing all it can to prepare for storms, said Mudd of the East Harris County Manufacturers Association. “Our companies care about the communities they work in,” she said. “Anything that makes our communities safer is where our focus is.”

Several companies expressed confidence that their sites on the Gulf Coast would hold up well during a hurricane or flood. Jim Harris, a spokesman for the Denka Corp., a plastics manufacturer, said its facilities operate “safely and within regulatory guidelines both during regular operations and when planning for emergency situations."

The risk management plan for Denka’s large facility in Reserve, Louisiana says it could release large amounts of chlorine gas during an accident or natural disaster. But Harris said the site is at no greater risk than the surrounding area, which he said is on relatively high ground along the east bank of the Mississippi River, about 25 miles from New Orleans. "In the memory of long-term employees, the site has never flooded, including during hurricanes Katrina and Isaac," he said.

Mitchell, of the Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership, says many companies express confidence in their facilities publicly. Privately, they know they’re in danger. “A lot of companies will tell you they reinforce their facilities so hurricanes wouldn’t affect them,” he said. “But a 23- or 25-foot surge? You can’t stop that.”

What can stop it, he hopes, is the Ike Dike.

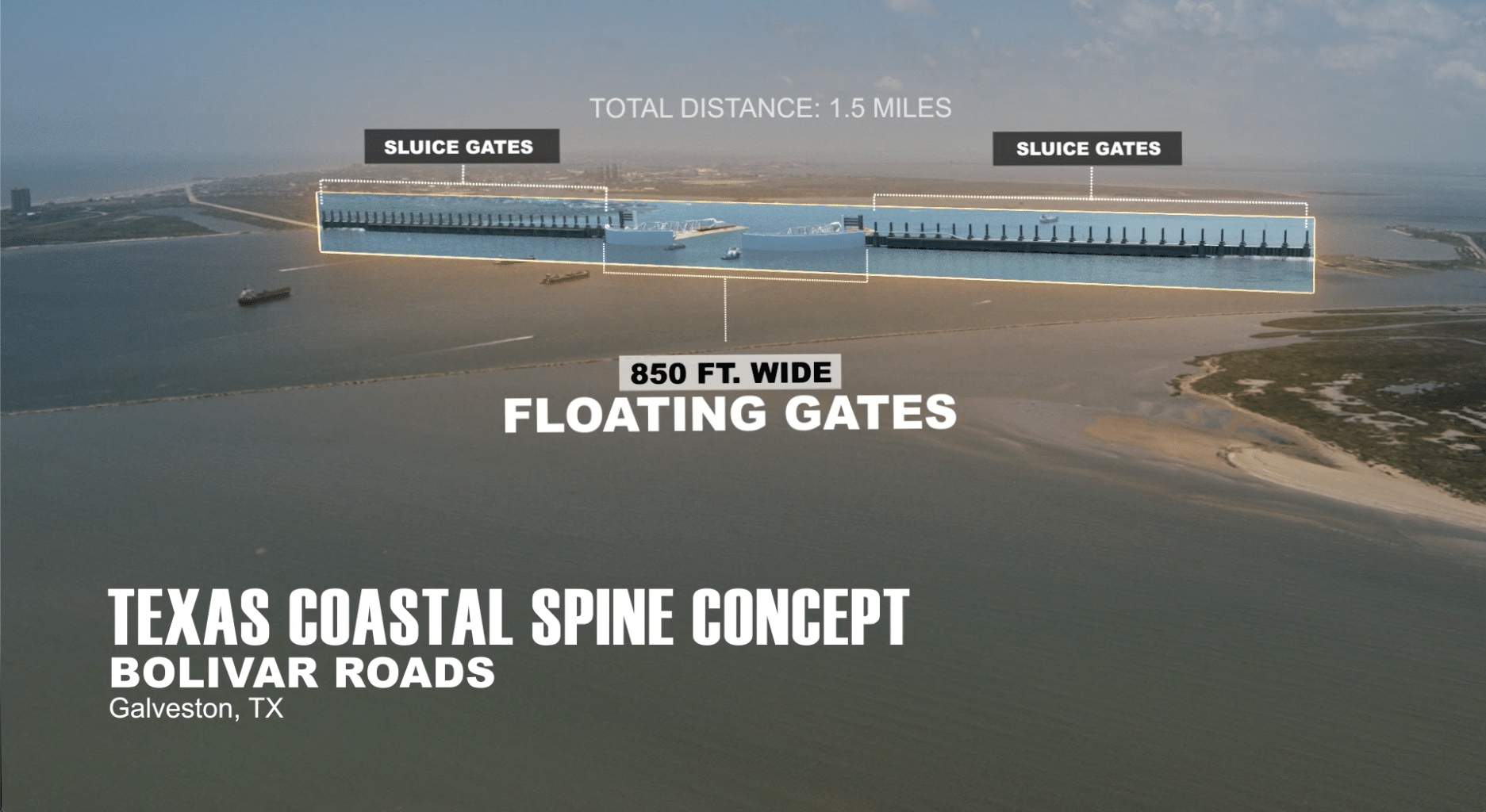

Still from a video presentation of the “Ike Dike” project. The coastal spine concept is based on successful flood barriers deployed in the Netherlands. (Texas A&M University Galveston / Space City Films)

The Big Solution:

Ike Dike

Kelly Burks-Copes stands near a marker for Fort San Jacinto on the windy northeastern tip of Galveston Island. It’s a spot where the Spanish, the French, the Republic of Texas, the Confederacy and the US Army have all taken turns building coastal defenses to protect Galveston Bay.

Now it’s Burks-Copes’ turn. She’s leading the US Army Corps of Engineers effort to build the Ike Dike, a $28.9 billion project that’s been in the works since its namesake storm battered the bay 13 years ago.

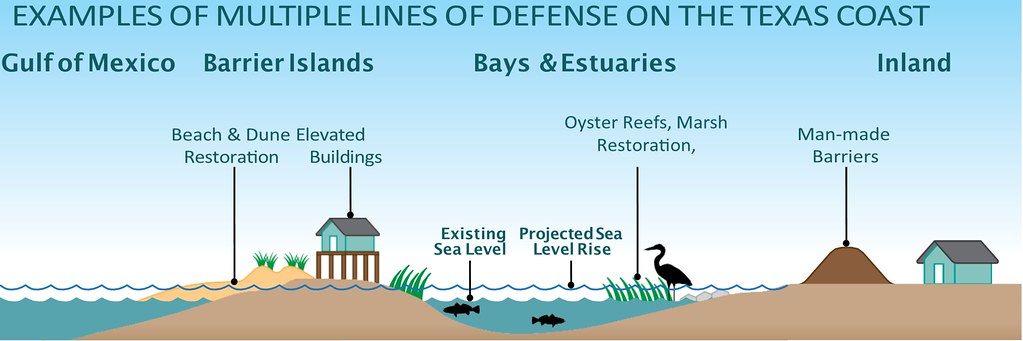

The Ike Dike would harden 70 miles of coastline with artificial dunes, huge gates, and a new sea wall that wraps around the city of Galveston. The project is so ambitious it may overshadow the coastal barriers in the Netherlands that inspired it. “If it’s not the largest surge barrier in the world, it’s certainly the world’s longest,” Burks-Copes said.

From where she stood at the old fort site, the Army Corps plans to build a series of gates spanning from the northeast part of Galveston Island to the Bolivar Peninsula, crossing the 2.5-mile channel connecting the Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. The span will include 15 vertical lift gates and four swinging gates, the largest of which would be 650 feet long. The swinging gates would allow ships to pass, and several culverts and small gates in the shallow areas would permit fish and shrimp to swim in and out.

The project would bulk up the “ring barrier system,” stretching around the backside of Galveston Island. Because this closed system of floodwalls, gates and levees could hold water as well as it keeps it out, the Army Corps plans to install six new pump stations to move rain or surge water off the island.

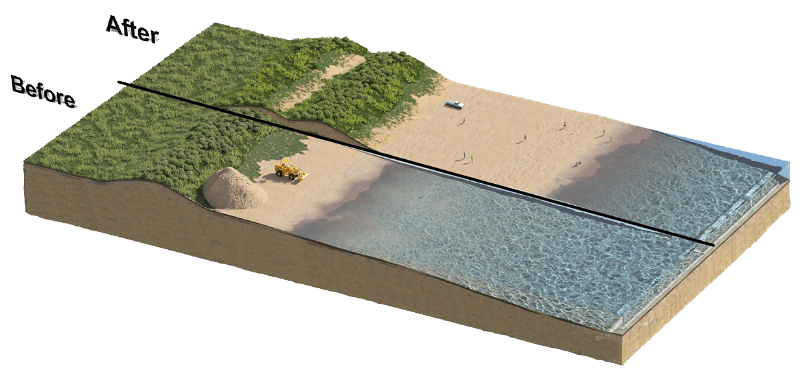

The decision to build sandy beach and 12- to 14-foot-tall dunes to protect about 43 miles of the coast has proven controversial. Bechtel, the Morgan’s Point mayor, and other Galveston Bay leaders want something sturdier than sand.

“That’s just going to wash away,” Bechtel said. “Storms that hit Louisiana—200 miles away—wiped out natural beaches all the way over on Galveston Island. We want a good, consistent barrier all the way across.”

But Burks-Copes said walls or anything taller than 14 feet would block views and access to the bay. “Beach access—for residents and tourists—it’s a way of life here,” she said.

The bulked-up beach and dunes are also a “nature-based solution” that will boost habitat for several species, including endangered sea turtles, which nest on Texas beaches more than any other part of the US Gulf coast.

“We have to be careful how we restore the beach,” Burks-Copes said. “For sea turtles, the type, color, and temperature of the sand is what determine the sex of their young.”

She concedes that the sand won’t stand up to repeated surges, but it can be rebuilt between storms. “The sand is sacrificial, but we can replace it fast,” she said.

The system won’t stop everything, Burks-Copes admits. Strong surges could overtop the walls and dunes, and Galveston will still need to evacuate during some hurricanes, she said.

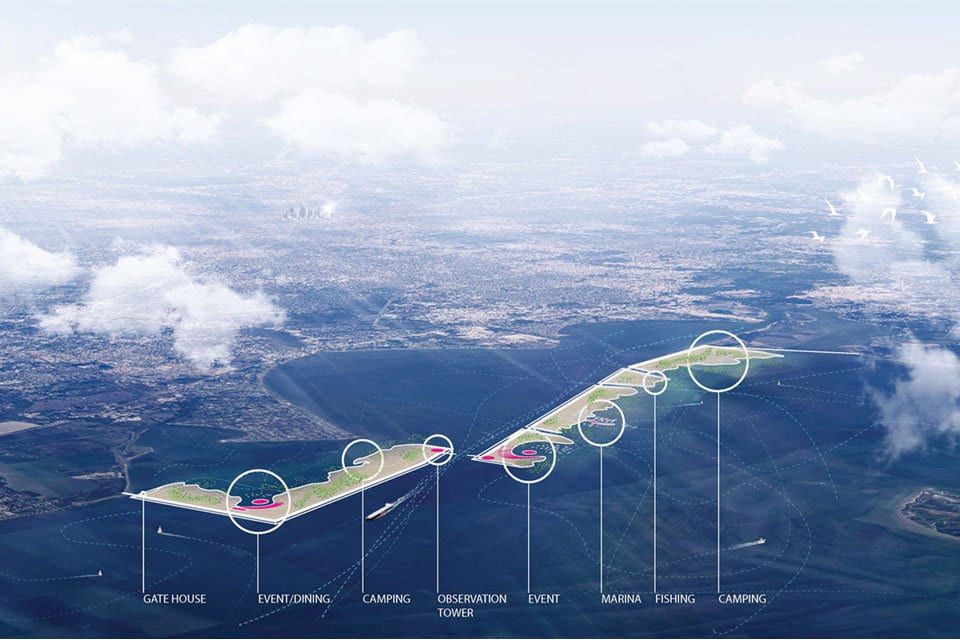

Blackburn has been promoting an alternative storm protection plan that he now says can complement the Army Corps project. Known as the Galveston Bay Park Plan, the $6 billion proposal would use dredged material to construct a string of islands in the bay that would double as surge barriers and provide about 10,000 acres of recreational space.

The Army Corps isn’t opposed to the Park Plan nor is it particularly for it.

“It’d be a redundant feature to what we’re doing,” Burks-Copes said. “It can take the edge off whatever remains of a storm.”

Jim Blackburn, co-director of the Severe Storm Prevention, Education and Evacuation from Disaster (SSPEED) Center at Rice University, favors the creation of a series of artificial barrier islands in Galveston Bay to complement the Ike Dike project. (Reuters / Richard Carson / SSPEED Center)

Bechtel says the Park Plan, which has far less momentum behind it and no funding, is little more than a distraction. The Ike Dike plan is already clearing what could be years of regulatory hurdles and has a much better chance of becoming a reality. But its immense price tag is a looming concern. Bechtel was recently appointed to the board overseeing the Gulf Coast Protection District, a new state body that has the authority to levy taxes and issue bonds to pay for the Ike Dike.

Texas will likely be on the hook for 35 percent of the costs, but the rest will have to come from a federal government that hasn’t shown much enthusiasm for the project. The state’s congressional delegation supports it but not with the passion that channels billions of dollars from a federal budget still reeling from the high cost of fighting the coronavirus pandemic. “We have lots of people who support the project,” Mitchell said. “Everybody will tell you they think it’s a good idea. But do we have a champion for it? No.”

If the project breaks ground in 2024, as scheduled, construction will likely take 19 years. “We’re looking at this as a generational project,” Burks-Copes said.

Mitchell says he knows what will speed up the process: a deadly storm. New Orleans got its long-awaited and hugely expensive storm protection system after Katrina. “If Houston gets a hurricane that kills 2,000 people like Katrina did, we will get a check the next week, and we will build our protection system in three and a half years,” he said. “In the second scenario—the one without a hurricane—it takes 20 years and every year we’re asking the feds for money.”

Burks-Copes hopes death and destruction aren’t the only motivators of political leaders. Despite the project’s high costs, she stresses that the Ike Dike is estimated to reduce structural damage by about $2.3 billion annually. “For every dollar spent, we save two in what we’re protecting,” she said. “When I say it pays for itself after one storm, I’m not kidding.”

But that one storm is yesterday’s storm, Blackburn said. Tomorrow’s storm isn’t going to act like Ike or the relatively weak storms the Ike Dike is built to withstand. “They’re building for a Category 1 or 2 storm, but it’s the 3s, 4s and 5s that we should be building for as our planet warms,” he said. “We have not caught up with the reality of climate change. Until we wrap our heads around what’s to come, we’re going to have to deal with more severe storms that cause a lot more industrial spills and kill a lot more people.”

A storm front stretches across Galveston Bay. (Louis Vest via Flickr; CC-BY-NC)

Keywords: Louisiana, Texas, flooding, hurricanes, sea level rise, toxic chemicals

Topics: Climate Change, Investigative Reporting, Multimedia

Interesting and worrying description of the risks deriving from this huge industrial infrastructure on US gulf coast. In my opinion, but rather then referring to Chernobyl I would compare it to Bhopal, if anybody remembers what Bhopal was and how many lives it claimed and it is claiming due to the land pollution.

Despite everybody mention Chernobyl as the worst man caused catastrophe, the incident at Bhopal chemical plant was way more and destructive.

On top of this, despite the threats to Louisiana from rising sea levels, the state’s government declared it a fossil fuel sanctuary. Willful ignorance isn’t enough to describe that.

None of this justifies destroying a barrier island, a barrier peninsula, and closing a major estuarine tidal inlet, especially without bothering to be honest about the environmental impacts of all that. The Corps improperly eliminated a more traditional flood protection alternative- levees closer to the actual areas of concern, combined with a gate at the mouth of the HSC- an alternative that would have far less environmental impact. They cavalierly eliminated this alternative in the EIS, explaining the reasons for doing so in just a few sentences. The elimination of this alternative was clearly inappropriate. The lack of substantive disclosure… Read more »